A woman turns toward the man beside her, to cup his face in her hand. They are sitting at the kitchen table at dinner time. He reads a newspaper while she sits with her chin on her fist and her eyes closed, and the light plays over her forehead. She is tall in the foreground, informal in a dark robe, and the way she holds herself shows the strength in her shoulders and forearms. She stands up to walk behind him, and he draws her down to him.

They appear in black and white photographs, in daily moments, warm and intimate, touched with tension when the world outside intrudes with hard news or hostility. And their images can be rare, and radical, in their courage. They reveal a depth of sadness and irony and strength, and a will to go on. As they are doing now, in Covid, on the streets in the Berkshires.

“Carrie Mae Weems is one of the premiere photographers in the country,” said Erica Wall, director of the Berkshire Cultural Resources Council and Massachusetts college of Liberal Arts’ Gallery 51.

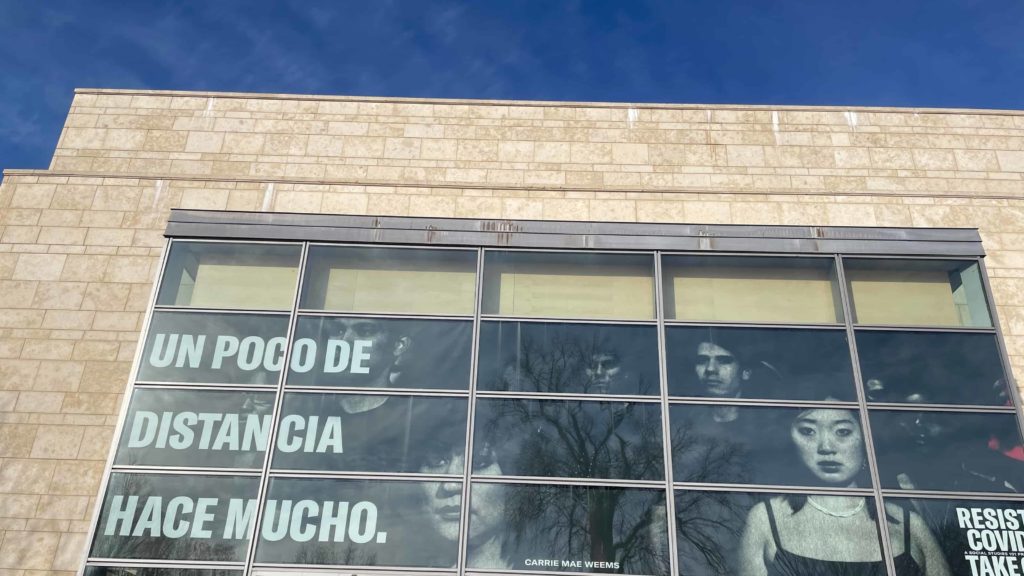

Weems is internationally known for her work in text, fabric, audio, digital images, installation, and video, and above all in photography. In the pandemic, she has created Resist Covid: Take 6, a new public work, bringing her photographs together with messages directly related to surviving in this hard time.

Carrie Mae Weems' 'Resist Covid: Take 6' comes to the Williams College Museum of Art.

A woman opens her arms to an uncertain world. These new photographs hold as many depths and contrasts in images and words, as they sustain and call for action.

Life is beautiful.

Don’t worry — we’ll hold hands again.

Thank the farmer, the shop keeper … the teacher and the custodian …

This must be changed.

Weems’ images have come to cities, across the country, from Los Angeles and Portland to Dallas and Houston, Savannah, Detroit, Boston and New York. They come into the community, outdoors in public places. And they are coming to the Berkshires in a broad collaboration across at least three communities, one of the first in a rural area, possibly the first in the whole U.S.

The exhibit here is taking shape in a partnership among museums, small towns and college campuses: Mass MoCA and the Clark Art Institute, the Williams College Museum of Art and the ’62 Center at Williams College and the town of Williamstown, the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts and its Gallery 51, Bennington College and its Usdan Gallery and the Bennington Museum.

In North Adams and Williamstown and Bennington, people walking downtown can see them now on billboards and bus shelters, on downtown streets, in farmers markets. They carry messages of health — washing hands, keeping a distance — messages thanking workers and encouraging people to come together and come through this time. And at the same time, they are making visible the affects Covid has already had.

Carrie Mae Weems' 'Resist Covid: Take 6' comes to the '62 Center at Williams College.

“Carrie Mae Weems is important to the region and to WCMA,” said Christina Yang, deputy director for engagement and curator of education at the Williams College Museum of Art.

It is powerful, she said, to have all of these places come together and bring her images to many places, in many media — to see the banners surrounded by snow and in the trees.

Wall agreed. It is powerful for her too, to see Weems’ artwork, and the people she celebrates, on billboards and on street corners in the sun. Work like the Kitchen Table Series in 1990 has won Weems national and international acclaim, and generations of young artists who have seen themselves in her work, and in exhibits at national museums, for the first time.

Weems illuminates the day-to-day, Wall said. She comes out of a history of artists who work in narrative and place themselves in their stories, like photographer and filmmaker Gordon Parks and pioneering photographer Lorna Simpson.

“She comes from a history within the black community,” Wall said. “She has shown the experience of women and amplified what that means.”

Weems reveals power within the black female community, she said, a history of women holding strength within the family, holding knowledge, working and raising children and playing many roles at once. And she looks clearly, necessarily, into the pain and trauma of living as a person of color in this country.

“Her work is as immediate now as it was in 1957, 1987, 2007,” Wall said. “It shows how much has changed … and how much is not changed.”

Carrie Mae Weems' 'Resist Covid: Take 6' comes to the Williams College Museum of Art.

Weems often collaborates with Rachel Chanoff, curator of performing arts and film for Mass MoCA and director of programming of the CenterSeries at the ’62 Center.

Chanoff came to the college and the museums, Yang said, to propose bringing Carrie Mae Weems’ project to the Northern Berkshires.

“Most of us in the art world know the impact of Carrie Mae Weems’ work,” Wall said.

She too explores power of public art projects — Gallery 51 has led MCLA in a broad community-wide project since last fall, in conversations around Hostile Terrain 94, a yearlong exploration immigration, in art exhibits and courses and community events.

In Take6 too, MCLA will create their own curriculum and public events along Weems’ themes, Wall said, to give voice to students feeling marginalized in the pandemic — to find and highlight resources for students, especially BIPOC students, and on a larger scale, including the BIPOC community in the Berkshires and Southern Vermont. They want to talk about what needs are not being met, especially in mental health.

She is working with professors in English, Health Sciences and Art, including Melanie Mowinski and Lisa Donovan, and students are studying Weems’ work. They talking with fellow students on campus, she said, and creating their own visual campaign, spoken word open mic and performances.

They are talking about making people visible here in the community, as Weems’ work, like the Kitchen Table photographs, has done and does in museums, in the art world, in college spaces.

“If we are one of the first (rural areas) to show these images framing BIPOC faces,” Wall said, “there’s a misconception that in rural spaces that we don’t exist. These images amplify our voices, and they are positive. We have awareness, and now we have visibility. At the end of the day, Covid does not discriminate. We’re in this together. These images in our areas are significant.”

‘There’s a misconception that in rural spaces that we don’t exist. These images amplify our voices, and they are positive. We have awareness, and now we have visibility. … We’re in this together.’ — Erica Wall

“I second that a hundred percent,” said Anne Thompson, director and curator of the Suzanne Lemberg Usdan Gallery at Bennington College. “This representation is important in Bennington and on campus.”

Covid has affected the whole country, Wall said. The virus affects everyone. But at the same time it has had a larger and stronger effect on some communities.

As the CDC has traced Covid’s effects across the country, they have seen it hit harder, at higher rates, in communities of color, Black and Latinx and Indigenous communities, and communities already facing the stresses of poverty, lack of education and economic hardship.

Weems is honoring teachers and nurses, bus drivers and farmers, all kinds of people who are performing vital work. She encouraging health practices, and now she is talking about the vaccine, pressing communities to make sure people will have access to it and encouraging people to get vaccinated when they can.

A history of mistreatment around the medical world and black families has led to skepticism around the vaccine in the black community, Wall said. Weems feels it is important that people have accurate information and understand it. She is empowering people do what they can to survive the pandemic.

“She’s not talking about numbers,” Wall said. “She’s saying we’re in this together, and we can get through this.”

This conversation around essential workers, essential protections and equities matters centrally to Thompson as well. She came into the Berkshire Take6 project through conversations with WCMA, she said, and she she has welcomed the chance to collaborate beyond her campus.

Usdan Gallery has been closed because of Covid, and she is interested in installations beyond the galleries, in the community and outdoors. As a curator, she feels a strong mission to lift up women and BIPOC artists, she said, and she is very much interested in working together with local art and community organizations.

This spring, Bennington is coming into the new semester with a banner outside performing arts center and posters on campus talking heath and about racial inequity. Some appear in the new commons building with its long open wall. A new poster on the vaccine, glimmering with blue sky, is going up near the site where people on the Bennington campus come for testing. Bennington will be a site for vaccines, she said.

She is reaching beyond the campus on its hilltop, toward people here that Covid has touched nearly. Weems’ project is connecting with activism about food insecurity in the region.

“CAPA — the (college’s) Center for Advancement of Public Action — has gotten a Mellon grant for food insecurity,” Thompson said, “because Bennington is a food desert.”

Bennington College will give out reusable bags to distribute at food stands and food shelves, with a calendar for all of the food shelves each week, and they will brings bags to farm stands with a map and information on food resources and donations.

Bennington has brought the project downtown to the kiosk at the four corners. Thompson has also reached out to the Bennington Museum, and they have joined in with banners and lawn signs.

In Williamstown, WCMA and the college are also working with the town, Yang said — the first time the museum and the town have collaborated this way. They are working with the BRTA on images to put up banners and posters in bus shelters.

“I’m excited for the bush shelters,” Yang said. “They’re something you’d ordinarily walk around.”

Now they can become fixtures in a community conversation, as people can take in and think over the images, like a landscape or a portrait. This kind of conversation is harder to have otherwise, she said.

The college has a mission to hold this kind of conversation, said Randal Fippinger, visiting artist producer and outreach manager at the ’62 Center, and to hold it broadly with many voices — a mission they have been pursuing for years, but not long enough or deep enough. The Williamstown community has been having its own conversations around equity in the town and local systems — in the last year, including the recent controversy over the Williamstown police department.

In one central piece at the ’62 center, a broad bright banner over the main entrance thanks communities in the area and on campus. They asked Carrie Mae Weems for permission to add to the text, he said, so that they could to speak directly to people who work on campus, food service workers, custodians

Bennington College has also reached out to her to adapt the work for their community, Thompson said.

She found herself considering posters where the message is to wear a mask and stay home. It’s a logical message to bring into a downtown community, she said. On the Bennington College campus, many people who will see are at work, and they have students, including international students, who can’t go home. She and the college have also talked with Carrie Mae Weems, and she learned that others including the Lincoln Center had considered the same questions.

“What I’m most interested in for our community,” Wall said, “is that we do this all the time, every day, as we think about what we’re doing, diversifying the campus, working for equity.

“There’s a fear around that. It requires practice, and you have to want to get better. It’s tiring. You have to find what motivates you … and it’s self-directed. You want everyone to feel respected and included.

“It’s frightening for all of the people (involved), and we don’t want to alienate anyone. If we’re not talking, we’re not building community, and we can’t move forward.”