The desk set is made of green glass with a pattern of dark leaves. The label names it Tiffany. Erin Hunt read it in fascination and mulled over these fine opalescent boxes. They would hold ink and paper, stamps, pens and blotter ends. And what would someone write with them, sitting at a desk in with the sun on the glass?

Here they are sitting on a shelf at the Berkshire Historical Society. Hunt took over as curator here a few months ago, and on a late summer afternoon, she and BHS’s new executive director, Lesley Herzberg, are exploring the attic.

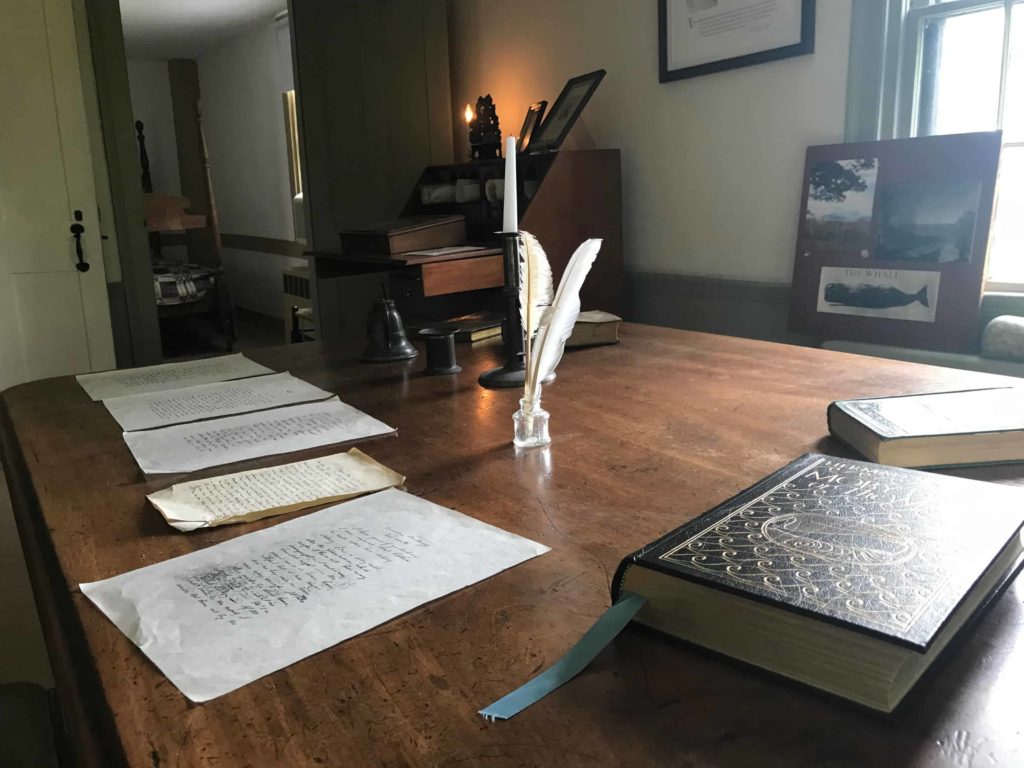

The collection here holds more than 6,000 objects, Hunt said. Some of the best known involve Herman Melville, who wrote Moby-Dick here. He lived in this historic yellow house, on the farm he called Arrowhead, from 1853 to 1864. But the historical society covers a larger field.

Herman Melville wrote Moby-Dick at Arrowhead, his historic house and former farm in Pittsfield.

Taking a new tack

Hunt became curator late last fall, balancing this work with her job as adminastrative manager at the Bidwell House Museum in Monterey.

Herzberg came to Arrowhead in the spring after almost 10 years as curator at Hancock Shaker Village, taking over from Will Garrison, who served as curator here and stepped in to lead when board member Betsy Sherman retired as director in 2015. Peter Bergman, Arrowhead’s communications director, will also retire after the summer winds town.

Herzberg has spent her first few months overseeing a busy summer and a celebration of Melville’s 200th birthday, she said, and now, as the summer rush settles, she has time to look ahead.

She and Hunt are brewing ideas for programs with local schools and partnerships with the Berkshires’ many town historical societies.

But first, they said, they are getting to know the collection.

Herman Melville wrote Moby-Dick at Arrowhead, his historic house and former farm in Pittsfield.

‘A goodly old elephant-and-castle’

Melville described his old house that way in an essay on the massive architectural feat at its center: “Twelve feet square; one hundred and forty-four square feet! Sir, this house would appear to have been built simply for the accommodation of your chimney.”

The top portion of the massive chimney rises through his central attic, and the timber frame is roofed in broad old boards — each plank is two feet wide and deep brown as a coffee bean.

Hardy objects are carefully stowed here: ceramic jugs, a butter churn, a lump of raw glass from a slag heap.

Herzberg remembered walking up the old road to the Richmond furnace once years ago and seeing old slag glass like this scattered along the road in chunks as wide as two fists, sparkling in the sun.

Trees that were young in Herman Melville's day stand far taller than the roof at Arrowhead.

From farmhouse to museum

There are three attic rooms here, and they are only a small part of the space housing the collection. More fragile objects are set in cupboards and archival boxes, here and in rooms behind the scenes on the second floor. On a shelf of ceramic cups, Herzberg opens a set of Mahjong game tiles in a miniature wooden chest of drawers.

Manuscripts, photographs and books have taken over the ground floor. Running a historic house as a museum can make housing a large and varied collection a new kind of challenge, she said.

Hunt has been looking through textiles recently. The historical society has gathered dresses from 1800 to the 1970s — wedding gowns, Worth gowns from Paris, fine lace.

“Every time I open a door or a closet, I find something new,” she said.

Curating a city

The collection reaches back to the early 18th century, Hunt said, and the society has wider goals encompassing all of the people who live and have lived on this land, Herzberg said, imagining an exhibit in conversation with the Mohican nation, the Stockbridge Munsee, and the Kanien ke’haka (Mohawk).

The collection began with the founder of the historical society, she said, and it has grown organically and gradually in the last 50 years.

Mira Hall, the founder of Miss Hall’s School, brought the historical society together in 1960, said Norma Purdy, a volunteer archivist who remembers the society’s early years.

In the society’s first years, Hall housed the society in her house on East Housatonic Street, and her collection of books and antiques seeded the collection.

The society originally focused on preserving old houses, said Barbara Bell, Purdy’s colleague and a longtime archivist and local historian.

BHS owned and restored three houses, including Myra Hall’s house and the Goodrich House on upper North Street — and sold them to buy Arrowhead in 1975. Preserving Melville’s house and his legacy has become a focus for the society, but it branches out through Pittsfield and up the mountains.

Melville’s Pittsfield

In the early 1850s, when the Melvilles moved from New York to Arrowhead, Pittsfield was nearing a hundred years old. The agricultural center was fast becoming industrial. The oldest known photograph of North Street shows the broad dirt road fronted with clapboard houses and white picket fences.

In the historical society’s archives, a sense emerges of a stately and sometimes muddy city. Here are elm trees along Bartlett Avenue, and hotels and restaurants near the railroad station. Morningside and Eveningside neighborhoods would grow up around them, named for the shifts of the mill workers who lived there.

The Pittsfield elm stood near a Bulfinch church on Park Square, Bell said, designed by the architect who created Boston Common and became architect of the Capitol in Washington, D.C. in 1818.

On summer days, Melville was making hay or hiking Mount Greylock to camp under the open sky. He and his wife visited Hancock Shaker Village with Nathaniel Hawthorne and his very pregnant wife, Herzberg said, and Melville and Hawthorne held a race around the Round Stone Barn.

The city on paper

Bell walks through the archives, showing collections of images, including the 19th-century photographer and Civil War veteran Edward Hale Lincoln. The archive is rich in maps and post cards, town records and vintage valentines.

She turned to scrapbooks from Arthur Palme, a General Electric engineer who devised a way to take photos of motion. He would shoot a tea cup, Bell said, and capture the flying pieces.

A file holds letters from Rachel Field writing to her cousin Margaret from Sutton Island, Maine, on a summer morning.

Field was born in Stockbridge, and she won the National Book award in 1935 for a novel set on the Maine coast, Time Out of Mind. She is known more often now for her Newberry awardwinning children’s book, Hitty, Her First Hundred Years.

“There’s so much room for learning here from things in the area you wouldn’t think about,” Hunt said.

Herzberg, looking through a file of clips from local newspapers, said “Here’s a Berkshire skunk farm.”

A local entrepreneur in Hinsdale apparently once decided to raise 40 skunks for their fur. The writer did not seem to have asked their neighbors how they felt about it.

Melville’s objects

Among the archives’ most striking artifacts, an original and valuable complete set of Melville’s works sits bound in green leather. This Raymond Weaver collection is the first of his works ever assembled, and they were brought together in 1920, decades after he died almost unknown.

They had just received a new book for their Melville library, Bell said: a collection of Melville essays written by professor Hiroshi Igorashi in Tokyo. An accompanying letter translates the title as Melville: A Whale Man Who Became a Speaker of True Things; the book is naturally written in Japanese.

The historical society has a growing collection of objects and papers relating to Melville and his family, though Hunt and Herzberg emphasize that the Berkshire Athenaeum has a large Melville collection of its own and often shares it generously.

This summer and fall, while Arrowhead is displaying a collection of Turner prints, Hunt has also curated an exhibit in the barn gallery of objects from the Melville family, and they are varied.

A sperm whale’s tooth may cause no surprise from the author of Moby-Dick, but a delicately inlaid wooden box carries a sobering history.

It is an opium chest, Hunt said. In 1850, the opium wars were devastating China, as the British East India Company illegally smuggled drugs into the country. A Melville relative trading in the east brought back the carved box as a curiosity.

On the far wall, a framed signature introduces a gentler international exchange. It is a work in micrography: The lines of the signature are made up of miniature letters, in a Jewish art form a thousand years old.

The artist, David Davidson, had immigrated from Polish Russia to New York, and a friend commissioned this gift for Melville’s father-in-law, Lemuel Shaw. Here, Davidson forms Shaw’s signature out of minute words, excerpts from a biography of George Washington.

Stories in everyday things

The collection is varied, Hunt said, and learning it is bringing her into new areas to explore. She had not expected, in curating this show, to wind up researching the history of opium pipes. But she has a background in material culture, in reading the stories an object can tell about the people who have used it.

Some stories are painful, and some are loving. And some are both. The most recent article in the collection had just to her from an unexpected phone call, she said. She took a box from her desk and opened it to show dark stones in a smooth band. It is an onyx and pearl mourning ring.

It comes to the society from Patricia James, who now lives in California. It belonged to her great-great grandparents, the Hatch family of Pittsfield, Hunt said. They lived on Linden Street and apparently owned a dry goods store in town.

The ring came to Alberta Hatch, James’ grandmother, who was born in Pittsfield in 1897 and is buried here along with other members of the Hatch family. A woman would have worn a ring like this to remember and honor the memory of someone she had lost, Hunt said. She would hold their name in her hand and warm in on her skin.