On a September day in Paris, James Baldwin described a bright, warm morning, as he waited at the Sorbonne for the Conference of Negro-African Writers and Artists to begin.

“There were people on the cafe terraces, boys and girls on the boulevards, bicycles racing by The boys and girls and old men and women who had nowhere at all to go and nothing whatever to do, for whom no provision had been made, or could be, added to the beauty of the Paris scene by walking along the river.”

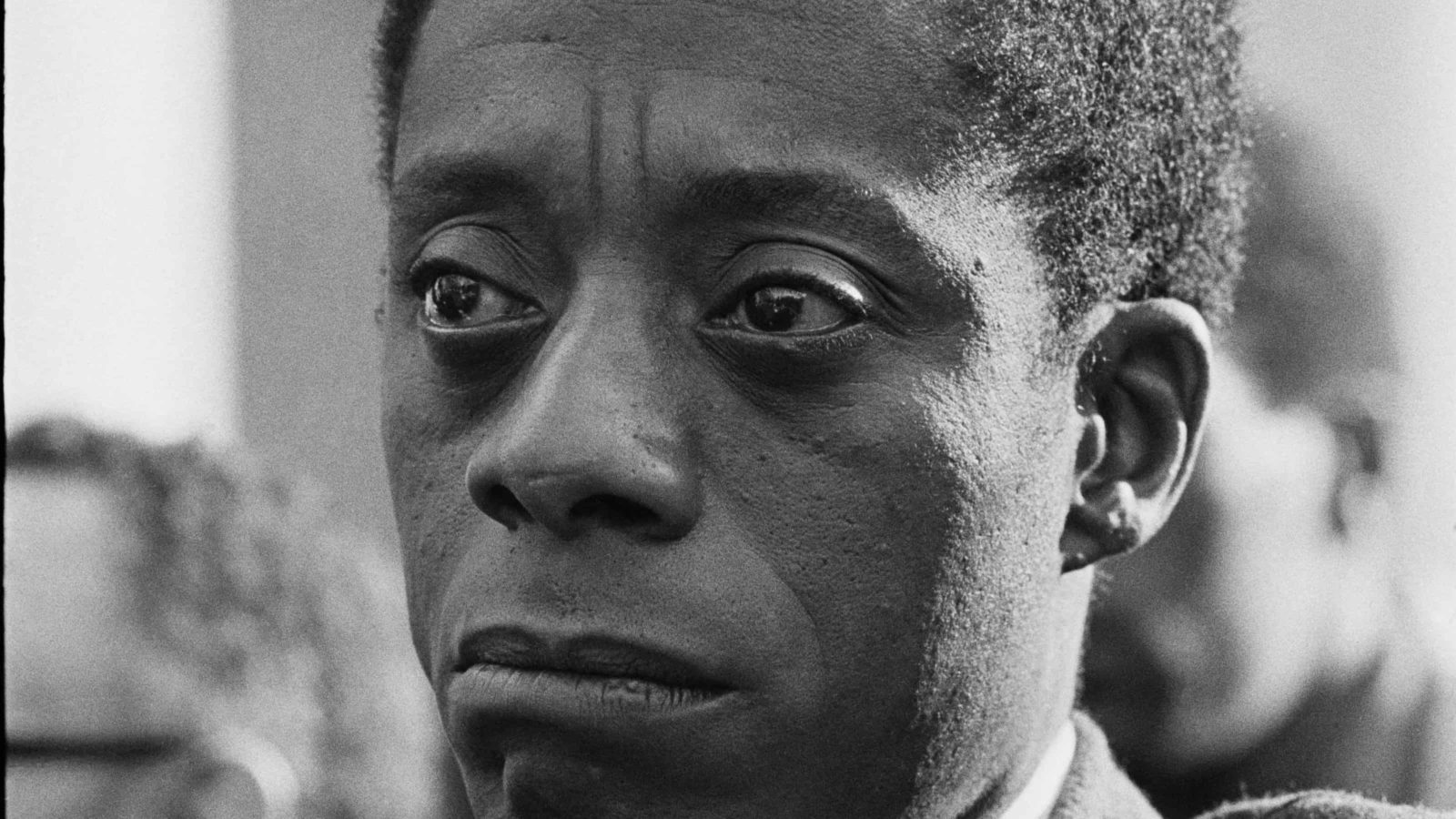

Baldwin was high in his career on that morning. He was known internationally as a novelist, journalist, intellectual, writer of more than 20 books, poet and playwright. And he was spending four days with colleagues and luminaries like novelist Richard Wright and Martineque playwright Aime Cesare, covering the conference for Encounter magazine.

Thirty years later, filmmaker Karen Thorsen set out to honor his life on film, and last summer she came Mass MoCA to screen her restored documetary, “James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket,” to lead a conversation and open the summer-long Lift Ev’ry Voice festival of African American arts and culture across the Berkshires.

“Think about slavery, about people held against their will,” said Don Quinn Kelley, a founding board member for Lift Ev’ry Voice. “He was free as a person. He always expressed himself fully — build your dreams, your hopes, your daily living, your future, the possibility of what can be. That’s what we celebrate.”

And who could begin the celebration better, he and Thorsen said, who better than Baldwin, who could face hostility, fear and loneliness and keep open to what came.

“Thinking about living through his times, what impressed me as a young person — he spoke his mind,” Kelley said. “He spoke truth always — he was never ashamed of who he was. In the 70s, that was a big thing for African-Americans: We are who we are. We do not need to apologize for who we are. For him never to have the need to apologize — it was inspiring.”

“My favorite book [of his] is ‘Giovanni’s Room.’ We all run away sometimes from who we are, but we can’t. He made a point of sayng ‘you don’t have to run.’ He saw this country. He saw the world.”

Thorsen first came to Baldwin’s writing in an American Literature course. She returned from a year at the Sorbonne to Vassar, she said, to read his accounts of his time in France, and his novels and essays. He spoke to her directly and clearly about matters as pressingly real to her as her own experience and the headlines in her daily paper — and she has seen students today connect and open, hearing him for the first time.

‘He spoke his mind. He spoke truth always — he was never ashamed of who he was. … We are who we are. We do not need to apologize for who we are. For him never to have the need to apologize — it was inspiring.’ — Don Quinn Kelley

Born in New York City, Baldwin had followed a writing fellowship to Paris in 1948.

“I left American because I doubted my ability to survive the fury of the color problem here. (Sometimes I still do),” he writes in an essay that ran in The New York Times Book Review and now appears, like the passage above, in his nonfiction collection, “Nobody Knows My Name.”

In the Alps, listening to Bessie Smith albums, he wrestled with what it meant to him to be American.

In her time abroad Thorsen, too, had asked herself questions about her country. Baldwin’s writing captivated her, she said.

She became editor at Simon & Schuster; a reporter and editor for Life Magazine and a foreign correspondent for Time Magazine. And in 1986 she met Baldwin himself. Working with Maysles Films, she began work on a documentary, a cinema verité, a film that would follow Baldwin as he wrote his next book. He wanted to talk with the children of Civil Rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., she said, people he had known all their lives.

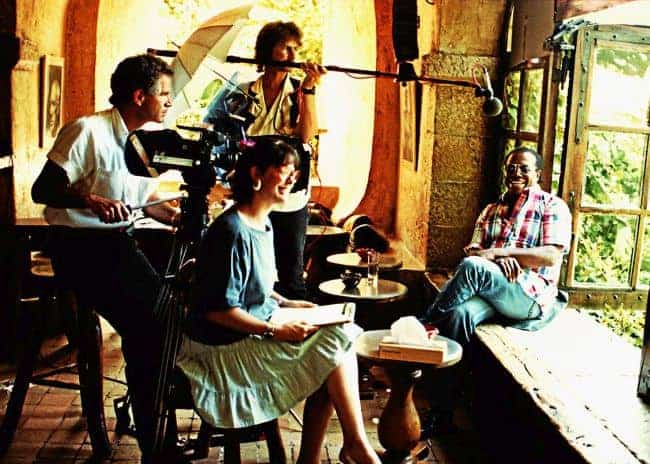

James Baldwin in 1965 drinks tea from a samovar in Istanbul, Turkey, his home for seven years, where he finished "Another Country," "Blues for Mister Charlie" and "Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone." Press photo Courtesy of Karen Thorsten

In 1987 Baldwin died, at 63. Thorsen could no longer film him living, teaching and talking — but she wanted all the more strongly to preserve and spread his voice, his anger and hope.

“The day he died, when I thought the film wouldn’t happen, I got a letter from him,” she said.

It made her feel that she would find a way forward.

She found, over time, archival clips of Baldwin from more than 100 sources, filmed on three continents. He moved people so strongly, she said, they would take time to hear him and film him speaking. She found a script from his Broadway play in his cellar in Southern France.

She realized she needed no narration — Baldwin speaking at different times in his life could tell his own stories.

“At age 30 or 40 or 50 he could finish his own sentences,” she said. “He was so consistent.”

Maya Angelou, Baldwin’s longtime friend, agreed to speak in the film and to read Baldwin’s words.

“She’s such a strong spirit,” Thorsen said. “She and he called each other brother and sister.”

Thorsen came to Angelou’s home in Winston Salem to film her. They met on President’s Day, she said, the one day Angelou had off from speaking and traveling — because, she said, she was black and a woman and not a president.

Last fall, in her last months, Angelou continued to work with Thorsen on the restoration, as her last and greatest gift to “her brother Jimmy,” Thorsen said.

The original film aired in 1989 on American Masters, and PBS described it as a reflection on “what it means to be born black, impoverished, gay and gifted.'”

Thorsen has come to restore the film now and take it on the road because Martin Scorsese, who knew the work, asked for a clip to use in a film he was making on Fran Liebovitz, who considers Baldwin a mentor. Coming back to the film, Thorsen felt a need to preserve it — and this summer’s tour celebrated what would have been Baldwin’s 90th birthday on Aug. 2.

‘He was free as a person. He always expressed himself fully — build your dreams, your hopes, your daily living, your future, the possibility of what can be. That’s what we celebrate.’ — Don Quinn Kelley

Kelley, teaching Baldwin’s work at the City University of New York across 35 years, felt the bitterness and strength in Baldwin’s courage and endurance.

“When you know ‘I am’ and people say ‘you are not,” there’s a loneliness,” Kelley said. “He stood up to say ‘I am’ and ‘I am’ and ‘I am.'”

“The trick is to say ‘yes’ to life,” Baldwin wrote. “It’s only this weird 20th century which is so obsessed with the particular details of anybody’s sex life. I don’t think those details make any difference, and I will never be able to deny a certain power that I have had to deal with, which has dealt with me, which is called love — and love comes in very strange packages. I’ve loved a few men. I’ve loved a few women. And a few people have loved me. That’s all that has saved my life.”

This story, updated here, first ran in Berkshires Week & Shires of Vermont in my time as editor there.