Renowned harpist Ann Hobson Pilot and composer-flutist Valerie Coleman are sitting in a pavilion with windows clear enough for the afternoon sunlight and the sound of classical musicians at practice to stream in.

A distant trumpet, probably played by an accomplished high schooler, plays a familiar, ascending fanfare from Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1. Mahler is one of Pilot’s favorite composers, she says — his parts are economical but deep.

“He never wrote harp parts with a lot of notes,” she said, smiling, “but the notes he wrote are important, put in a certain place … And French Impressionistic composers, Ravel …”

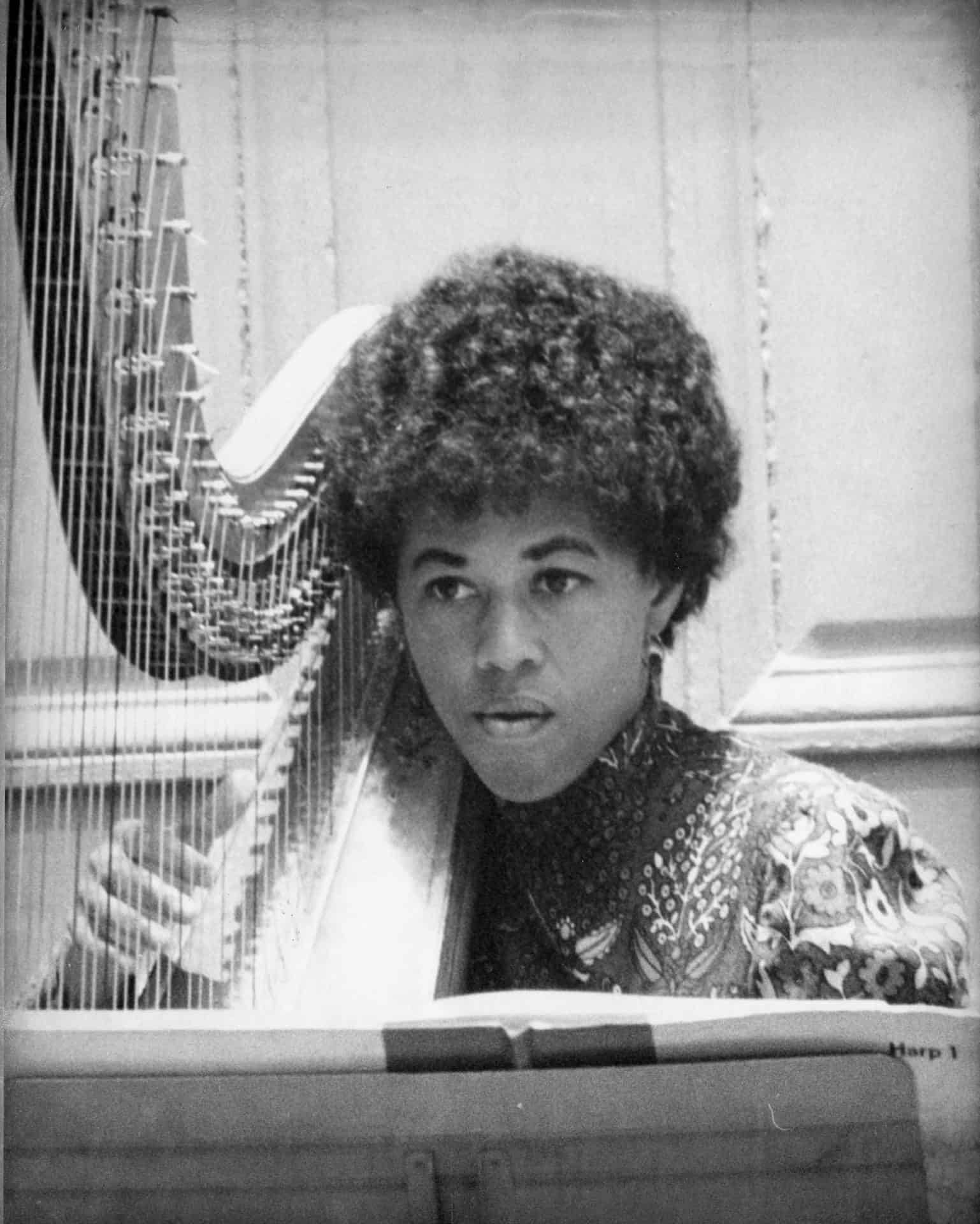

Ann Hobson Pilot performs as harpist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in the 1970s. Press photo courtesy of the BSO

She recalled playing his Introduction and Allegro last month at the Library of Congress, with an a group called the Ritz Chamber Players, internationally acclaimed musicians across the African diaspora.

The library overlooks the Capitol building, she said, and they were performing Ravel in a wide-ranging program — including William Grant Still, whose work Tanglewood has honored this month — but they were in the Capitol in June, just after the Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade, when the streets were blocked off because of protests.

This week, she is here on the grounds of the Boston University Tanglewood Institute (BUTI), a summer training camp for talented young musicians aged 10-20, just up the road from Tanglewood, where Pilot performed with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) for 40 years, serving as assistant Principal Harp from 1969 to 1980 and Principal Harp from 1980 until her retirement from the orchestra in 2009.

On Sunday afternoon, at 1:30 in Ozawa Hall, the BUTI Young Artists Showcase will perform a free concert celebrating Pilot, who directed the BUTI Young Artists Harp Program from 2002-2021, in a program of BIPOC composers, many of them women, and two of her former students, now accomplished harpists, will return to perform and speak in her honor.

Musicians rehearse with a Boston University Tanglewood Institute harp workshop. Press photo courtesy of BUTI

Coleman’s own new piece, “Ashé,” will premiere then – she is here this summer as a BUTI instructor, and a widely recognized musician and composer. As a Grammy-nominated flutist, she has earned national awards including Chamber Music America’s Classical Commissioning Program, and in October 2021, Carnegie Hall presented her work Seven O’Clock Shout, commissioned by the Philadelphia Orchestra, in their Opening Night Gala concert.

Through the conversation, Pilot looked back across those years. She turned over memories — playing at Tanglewood with James Galway on flute, or the Symphonie fantastique with four harps, touring through Europe with the BSO and James Levine and playing Mahler, and traveling across Asia and Africa with the orchestra and with her husband, Prentice Pilot, an acclaimed musician himself on double bass with the Boston Pops for 22 years and on jazz saxophone.

Acclaimed composer and flutist Valerie Coleman will premiere her new work Ashé at BUTI. Press photo courtesy of the artist

“We’ve had some wonderful experiences,” she said, “I say we, my husband and I.”

Her career – as a soloist, orchestral player, and educator – has been illustrious from her early days onward. After studying with Alice Chalifoux at the Cleveland Institute of Music, she performed for three years as principal harpist of the Washington National Symphony, from 1966 to 1969. When Arthur Fiedler came to guest conduct, he invited her to audition for the Boston Pops and the BSO. She was initially unsure about taking the new job – she eventually did so on the advice of George Szell.

The world heard her transcendent musical talent first through invisibility, and then through wide visibility. Blind auditions for orchestras began in the year when she came for her audition, she said – an opaque screen separated the musucians from judges, so that the judges would choose by sound alone.

Pilot recalls that widespread adoption of the practice began when cellist Earl Madison and bassist Art Davis, two Black musicians, were denied from the New York Philharmonic, suspected racial prejudice, and took action that challenged the orchestral world’s hallowed façade.

Ann Hobson Pilot performs as harpist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

“They sued the New York Philharmonic,” she said, “and I think that’s what encouraged orchestras to start adding the screen, so there couldn’t be any discussion about discrimination.”

In 1969 she became the first African-American woman to join the BSO. She would be the first African-American to receive a BSO principal appointment, and the only Black musician in the BSO for 20 years. As she stepped into her role with the BSO and the Boston Pops, she became known across the country.

“This changes my whole perception on time frame,” Coleman said, “on when society, on when orchestral society, this world that seems so exclusive — that Black musicians were able to win these jobs. This is like the ceiling breaking in so many ways and different times, way earlier than I thought.”

In the 1970s, Pilot said, every Sunday night either the Boston Symphony or the Boston Pops would perform on television. And the nature of the orchestral world of the 1970s made her constantly and acutely aware of the pressure. She shared stories of colleagues who deliberately dismissed or denigrated her due to her race, even on her first morning with the orchestra.

“It was such a demanding job,” she said. “Being the only Black player is a demanding job, but you know, being the principal harpist of a symphony like this, I just felt like I could never make a mistake. I had to be perfect all the time — that’s the way I was living my life. To try to maintain my own, personal excellence as opposed to being a rabble-rouser or anything like that.”

‘They were saying ‘I’m the violist with the Portland Symphony, and I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing now if it wasn’t for you.’ — Ann Hobson Pilot

She and Coleman both acknowledged the challenges BIPOC musicians and composers have faced, and face today.

“I was the only Black player in the BSO for 20 years,” Pilot said. “Then Owen Young joined the orchestra as a cellist, and we were two Black musicians for 20 years, and then I left, and he’s been there by himself.”

She looked to Angelica Hairston, Pilot’s former student and now an acclaimed harpist and activist in Atlanta, who will speak on Sunday — and one of Pilot’s students with BUTI years ago. As she works with Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Morehouse and Spelman Colleges, the Sphinx Organization, Boston Conservatory at Berklee, NPR’s From the Top and more, Hairston is also director of Challenge the Stats, an organization she has formed to challenge inequalities in the classical music field — according to her mission statement, only 4.2 percent of US orchestral musicians are Black or Latino.

Internationally acclaimed composer and violinist Jessie Montgomery stands with her violin. Press photo courtesy of the BSO and the composer.

“So things are trying to change,” Pilot said. “I never would have thought it would have taken this long, but now I think with the pressure of racial justice and all of that, things are changing. So hopefully it will.”

Coleman shares Pilot’s cautiously optimistic outlook regarding the orchestral world’s progress toward racial justice. “I think there is effort, but it remains to be seen if this is a performative thing that is an answer to the times to save ticket sales, to save face, to save an organization’s legacy or to inoculate itself from accusations, or if it is truly a movement toward diversifying the music for the sake of moving music forward.”

At the very least, within the last five years, Pilot has seen the depth of change she herself has made. In 2017, she said, she received the League of American Orchestra’s Gold Baton award – the organization’s highest honor.

“It’s an award that Leonard Bernstein had gotten, and Copland,” she said.

She went to Detroit to receive the award, and afterward at the reception, young Black musicians kept coming up to thank her.

“They were saying ‘I’m the violist with the Portland Symphony, and I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing now if it wasn’t for you, because we used to watch you on Evening News,” she said. “… They would watch Evening at Pops and Evening at Symphony on television, and they would see me perform and think I can do that too.”

“I was just so blown away — that I had been a trailblazer without realizing it.”

She looks back too on her influence within the BSO and her longtime colleagues there. When she retired from the BSO in 2009, James Levine asked her what she would like as a retirement gift, and she asked for a harp concerto. And then he asked who she would like to write it, and she said, John Williams. She had often worked with him and performed his music.

‘I was just so blown away — that I had been a trailblazer without realizing it.’ — Ann Hobson Pilot

He said at first, “No, I could never write for the harp. The harp is a difficult instrument to write for — I could never do that.”

Recalling the moment now, she smiled.

“Every piece he writes has a big harp part in it,” she said, “… so we worked on it, and he agreed to write it. And it was an incredible experience for me, because he doesn’t do email, so … he would write to me with his questions in snail mail. I’d open the mailbox and say ‘Oh, here’s another letter from John Williams!’ And one of them, he signed it and said ‘You know I’m your biggest fan.’”

Ann Hobson Pilot holds a bouquet and stands beside John Williams with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Press photo courtesy of the BSO

He called the new work On Willows and Birches, and he dedicated it to her. She played it that fall, she said, at the opening of Symphony Hall in September and at the opening of Carnegie Hall on October 1 — and she played entirely from memory. And on October 3 they dedicated an entire performance for her, which included Debussy dances and a piece by Elliot Carter, and John Williams’ piece.

“At Carnegie, there was a pianist, Evgeny Kissin,” she said — “I believe it was the Chopin Piano Concerto — so I have a poster of that at Carnegie Hall, and his picture on the front, and mine next to it,” she said, laughing, “like ‘did I do that?’”

Coleman returned Pilot’s laughter — “I’m just in awe being in the same room as you, honestly.”

She too has learned from Pilot and her music.

“Every composer is learning to write better for harp,” she said. “… The feeling that I get when I talk to a harpist about writing for harp, I just feel like I’m in Paris, and I want to speak French. I want to give justice to it … but then there’s just so much that I don’t know.

“… Harpists are the champions of new music and teaching composers. You guys are on the front line of teaching us how to write for this incredible instrument that has so many different tones and its own percussion key, with the different pedals … I know that you’ve been, as harpists have been, on the front lines. You especially have been on the front line in terms of helping us composers really comprehend. You’ve made it accessible for us. So I’m in awe.”