Pierre Auguste Renoir is known as a painter of optimism. His scenes brim with light and color. Adriatic blue water laps close enough to touch. Men and women sit at cafe tables, laughing under lime trees and lanterns. Couples waltz outdoors on warm nights.

He is one of the founders of Impressionism, and his work forms the core of the Clark Art Institute’s permanent collection. And on the centennial of his death, the museum will consider an aspect of his work senior curator Esther Bell says no other exhibit has focused on before — the nude.

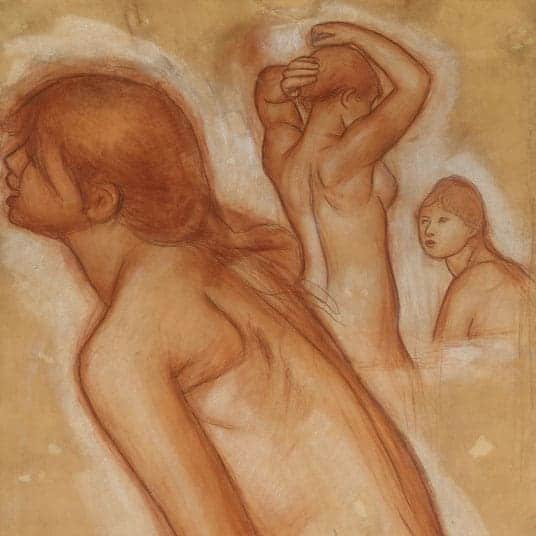

Renoir — The Body, the Senses follows one theme into a broad look across the arc of his career and sets his work beside his mentors and equals — Gustave Courbet, Edgar Degas, Suzanne Valadon …

Renoir painted the nude body often, over more than 50 years, Bell says at the museum on a spring morning. And he almost always painted nude women. They are young women, fair, sunlit and often in the water. And they have caused delight and controversy, and conversation, in his lifetime and today. They beckon to people who have seen them as active and beautiful or as passive reflections of desire. Their bodies curve, sensual and tangible or dissolving in a fall of golden rain.

Renoir returned to them regularly all through his career, Bell says, in many different ways. As he grew more established and independent, he painted more than 200 nudes between 1900 and 1919. But he had been painting them since the 1860s, in his student days.

“To be a properly trained artist, you had to master the human form,” Bell says.

Painting the bare human body was not only a tool or a student exercise, like an arpeggio. It was an artistic ideal, a subject any painter had to render beautifully.

Renoir came into the studio with a need to prove himself. He came from a working-class family, and he had supported them as an artisan in the porcelain factories of Limoges, Bell says. He had put himself through night school, surrounded by rich friends, like a first-generation college student with a scholarship, anxious to survive in a new world.

He would have drawn from models in class, Bell says, and from Greek and Roman sculpture at the Louvre, where he could get in free on weekends. There he also found the colorists — Titian, Rubens, Delacroix. The first painting the Louvre bought from François Boucher, Diana Leaving Her Bath, left him breathless.

“Renoir called it his first love,” Bell says.

His influences were not all mythological. He also revered Gustave Courbet, a painter known for his realism in the 1840s and 1850s, and Renoir’s early work shows both romance and modern life: a bather with a small dog, or a nymph by a Stream.

As he emerged and began to establish his career, Renoir moved from the official Salons run by the academies to the Impressionists, who moved against the current and held their own shows in the 1860s to the 1880s.

His work became lambent, Bell says, ephemeral, dissolving in sunlight. He painted his Blond Bather and The Onions (a well-known work in the Clark’s collection) in the same year, and on the same journey, and the light dances on their skin as it plays on the surface of the water.

He was 40 then. He was taking the trip to Italy that most of his French contemporaries had taken as young men, Bell says, and he was encountering Italian Renaissance paintings up close for the first time. Raphael awed him, and the classical grandeur of sculpture.

And the Blond Bather, floating in the bay of Naples, was his 20-year-old mistress. Her name was Aline Charigot. She later became his wife, but when he painted her here she was his lover and his model, as Colin B. Bailey explains in the introduction to the catalog; Lise Tréhot, Renoir’s first model and first love, also modeled for him for many nudes.

Martha Lucy, in her own essay in the catalog, speaks frankly of Renoir presenting women for the pleasure of gazing at them — for sexual pleasure and desire, erotic allure, an invitation to caress.

Their dreaming expressions have prompted some art historians to wonder whether the woman in the painting, basking in the sun, feels any of the sensual pleasure he captures in the golden light, the blue Mediterranean water and the long hair falling on her bare shoulder. Tamar Garb argues (again in the catalog) that Renoir’s women exist “without thought, conflict or even self-consciousness.”

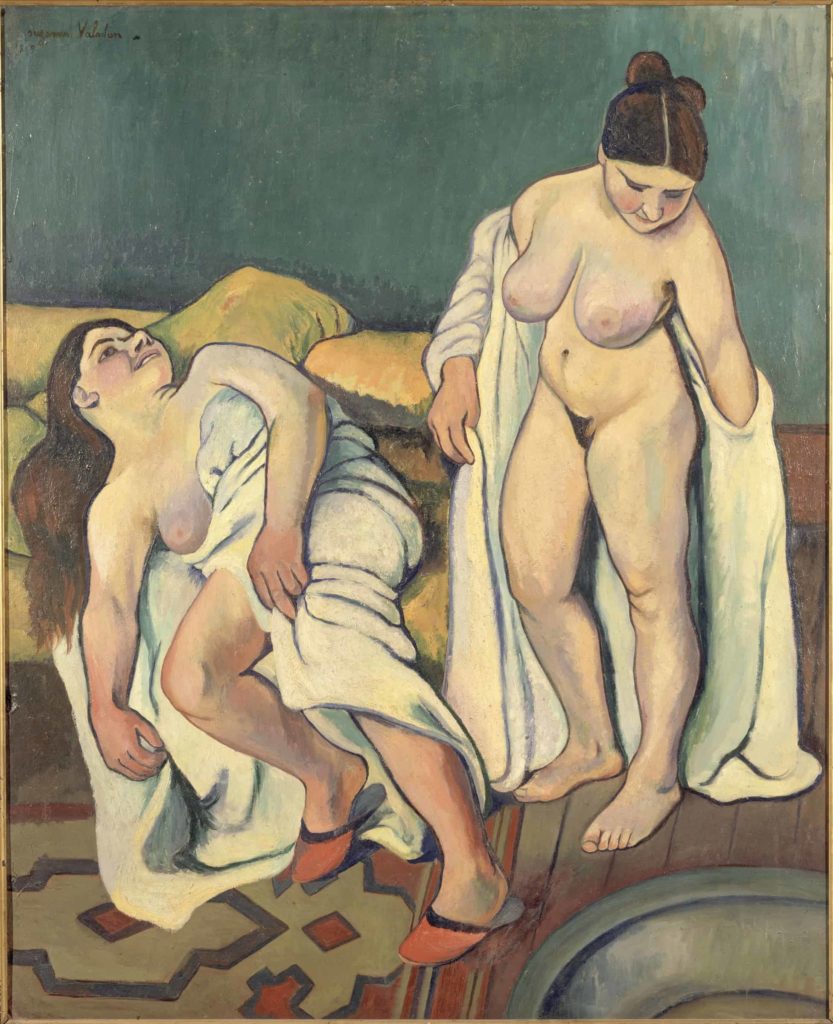

Suzanne Valadon might have an answer, in her own work here. She was a model, Bell says, and she became a highly successful painter, and one of very few women at the time to paint a nudes, men and woman.

“(Her women) are not idealized,” Bell says. “They’re looking at you head-on — they’re real women, not disguising their imperfections.”

Women in Renoir’s time did paint from models, Bell says, but rarely. Women could not study at most art academies in Paris then; they struggled to find teachers, studio space and support for their work, and the idea of women painting or drawing from a model strengthened public opposition to them.

Valadon also knew what it was like to be one of Renoir’s models, and the show will take them into account. Paintings of nude women can raise difficult questions, Bell says, about power dynamics between men and women, and between the painter and the model, and about a woman’s background, her class, and her mind and soul.

“There is great beauty in these paintings,” Bell says, “but they also raise questions about style, taste, gender, critical reception, identity and much more. (These ideas) have certainly been at the forefront of our thinking as we have worked on this exhibition.”

The women in these paintings are all young — some in their teens, or younger. A few are called jeunes filles in the titles of the works, young girls (in comparison to jeunes femmes, young women). These few are mostly clothed, among the naked nymphs and bathers. Their gowns slide from slim shoulders, and they sit quietly. Their rounded faces and small hands and slight build suggest they are not yet fully grown.

“In that time, it was common for teenaged girls to work as models,” Bell says, “either clothed or nude – in the Académie des Beaux-Arts (from 1863) as well as in private studios and workshops.”

She has worked to know Renoir’s models, she says, to find their names, to understand their thoughts and feelings and the conditions of their lives.

Over time, as Renoir’s style becomes more Impressionistic, the women he paints become less recognizable. As he moves to to the south of France in the 1890s, Bell says, his style takes another shift. Bodies take on mass and volume, but they lack form and structure, almost boneless.

Lucy sees in Renoir’s later work a celebration of the sense of touch, of organic and natural forms in a time when machines were becoming more powerful. His layers of paint for tactile surfaces, appealing to the hands as well as to the eyes.

“He used to say ‘I like to run my hand over a painting,’” Bell says, agreeing.

In his last years, as his sons fought in the trenches, he stiffened with rheumatoid arthritis until he needed help to pick up a brush … and he held on to idealized images of sunlight and happiness.

“He was tired after World War I,” Bell says. “Death has no place in this scene.”

And so his image evolves, brightly colored and complex — an old man painting young women — an artist with pain in his hands, at the end of a world war, painting light.