A woman stands in sunlight, and she looks out with a level, intelligent and sombre gaze at a world where a few generations ago she would have been enslaved. A soldier returns from duty in Afghanistan to face people who turn away on an American street.

At Mass MoCA, 16 artists are searching for firm ground in a world that can feel increasingly fake and absurd.

“What does feel certain and real is the power and the certainty that comes from being an artist with a voice,” ” said Denise Markonish, the curator of Suffering from Realness. “I think that is the most real thing these 16 people have, that cannot be denied, and that cannot be taken from them.”

The artists in this show are suffering, she affirmed, because powerful forces have tried to define the ‘real’ world as one where they don’t exist. Those forces can come from sources near or far from the artists’ daily lives — from national leaders or their own families.

Against that pressure, they are searching for reality in themselves, in their lives, in their pasts and futures. They find reality in the place where they live and with those they love, in the pain they have lived through and the people who hold them.

As she has talked with them, Markonish said, the artists have talked repeatedly about the ways they have fought to be themselves, but even more about the care they have given and felt. They have come back, over and again, to the ways people can lift each other when the world feels overwhelmed in despair.

Who decides what is real?

Markonish sees this show as a sequel to a group show she curated 10 years ago —These Days: An Elegy for Modern Times. The U.S. was moving then from the Bush years into the Obama administration, she said.

Today, she sees another political shift. In the exhibit description, she quotes British filmmaker Adam Curtis: “Our world is strange and often fake and corrupt. But we think it’s normal because we can’t see anything else.”

Realness feels ungraspable, she said: “Realness has subjectivity in one moment and the next. What one person sees as real, another may not.”

Robert Taplin brings a kind of absurdist protest and grief into sculptures of the clown figure of Puncinella from the Comedia del’Arte, who became the puppet of the Punch and Judy shows.Taplin sees him as an everyman trickster, Markonish said, a mischief-maker and a stand-in for the ills of society.

At the top of the stairs, at the entrance to the show from the main door, he stands mutely in Punch makes a public confession.

“We all have a lot to apologize for,” Markonish said.

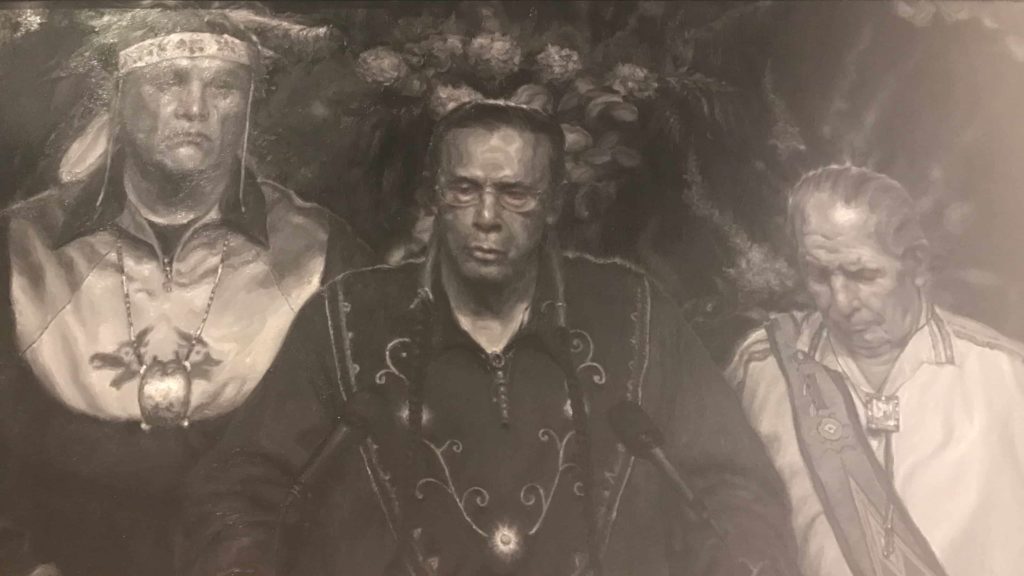

She feels a similar tension and silence in Vincent Valdez’ images of people from many backgrounds standing at a podium, not speaking — in images inspired by the memorial of Muhammed Ali — and in Robert Longo’s black and white images. Longo’s scenes look like photographs, but they are also drawings.

Longo has been working on this series since the 1980s, Markonish said. He has drawn inspiration from media images. A player with the St. Louis Rams holds his hands up in “don’t shoot” position as a protest after Fergusson. He stands on the field haloed in light.

Longo reveals cycles of violence, Markonish said, from the war in Viet Nam to the head of a stone sculpture lying in the remains of a temple ISIS destroyed.

Nearby, another sleeping head rests on marble. Wangechi Mutu has created a woman’s head, shining like brass in sunlight. Markonish can see tension in the woman’s lips and neck, as though she is not asleep. She is not wholly resting.

Mutu’s work struggles with the way Africans and women often see themselves represented, Markonish said, looking to the next pedestal, where a hand with brightly painted nails holds a machete.

Titus Kaphar's glass bust of George Washington holds a liquid darker than blood in Suffering from Realness at Mass MoCA.

‘Who lives, who dies, who tells your story …’

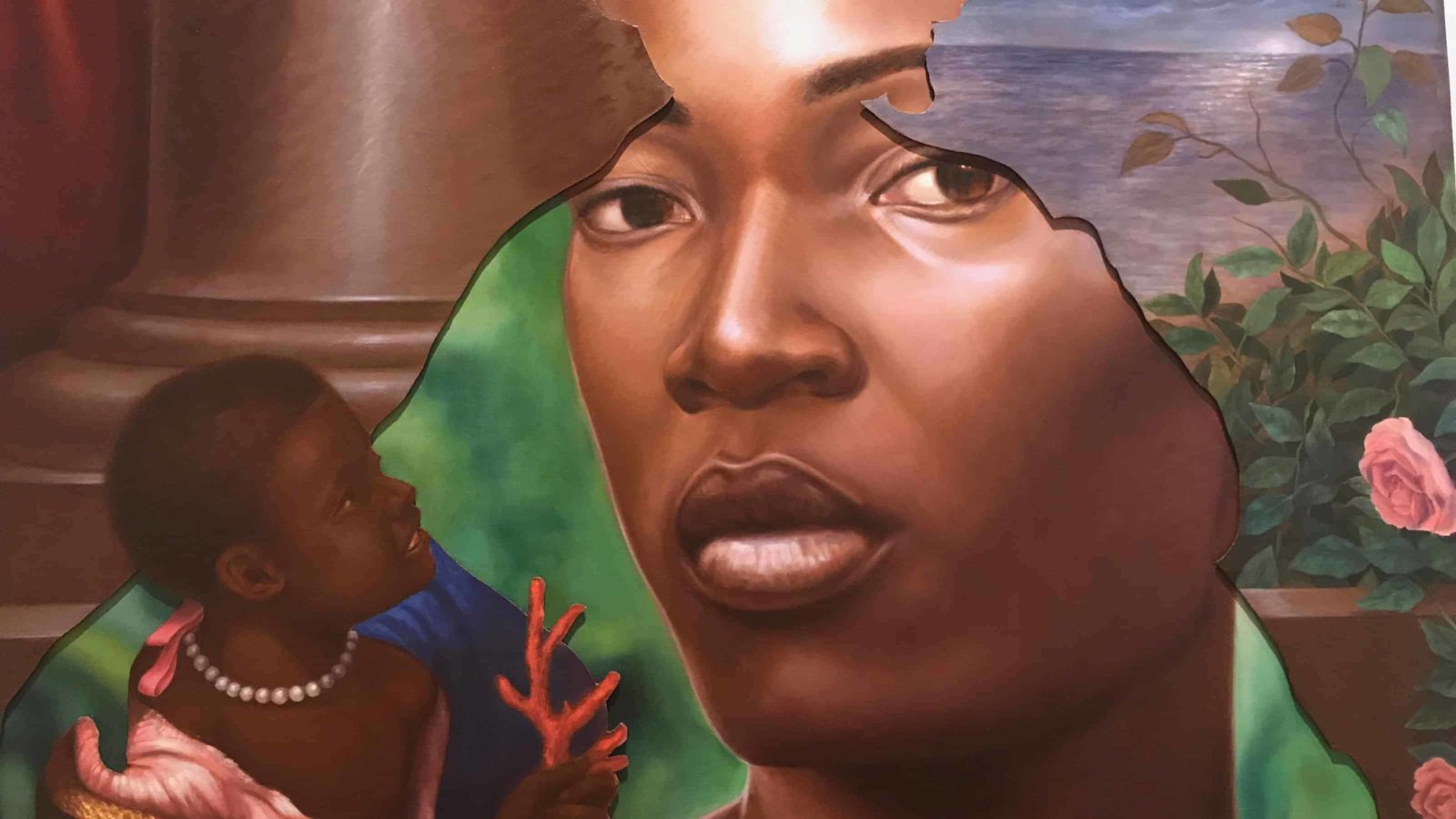

In visible and invisible faces, Titus Kaphar also asks who tells stories, and which stories get told.

He paints the portrait of a contemporary woman, and she stands in the sunlight with her shoulders back. She is young, and she is black. She looks out from a space cut away from a second painting; the two images are layered, one on top of the other.

“He is allowing the past and present on equal planes,” Markonish said.

In the image on top, Kaphar has removed the shape of a figure. Someone was standing at the center, and a young woman remains kneeling in the foreground, holding out a nautilus shell filled with pearls. She looks like a young enslaved woman helping a wealthy white woman to dress. But now, the portrait looks out from that space, and the woman holding the shell is looking into the contemporary woman’s eyes.

Kaphar is using art to tell untold stories. He asks what stories are told and who tells them — what stories are remembered, and what stories have been lost.

Beside them, he turns a monument inside out. A traditional form of George Washington on horseback has become a set of fragile shapes in glass. Kaphar made a mold in wood and then blew glass into the mold, and the empy relief sculpture darkened as the wood singed.

Beside it another blown glass vessel holds a dark liquid, sealed with a cork. The liquid is a mixture of rum, molasses, tamarind, tumeric and lime. And the glass vessel is shaped into George Washington’s head. In a historical account if his travels in the West Indies, Washington traded an enslaved man for these things, Markonish said.

Kaphar seems to lift that man, to call for his story and show its absence.

Vincent Valdez' images in Dream Baby Dream honor speakers at the memorial of Muhammed Ali, in in Suffering from Realness at Mass MoCA.

What happens to a dream deferred

A few steps farther on, Vincent Valdez and Adriana Corral are telling untold moments in the history of Latinx people in the United States.

Corral grew up in El Paso, near Juarez, Markonish said, and she also talks about what doesn’t get talked about. Here she has collaborated with Valdez on Requiem, a sculpture inspired by a drawing of his of a bald eagle lying on its back, dead.

In this collaboration, Corral and Valdez asked 243 people to submit a date important to them and explain what that day means to them. She carved the dates into the wall of the gallery, in light numbers against a light wall.

She burned the wood shavings and the pages of writing, and she rubbed the ash onto the sculpted Eagle like a patina, so that the dead bird seems to have been burned.

Valdez comes from San Antonio, Texas, and he and Corral both live and work now in Houston. Sharing space with Requiem, he has also contributed a series of paintings, Dream Baby Dream, inspired by film footage of Muhammed Ali’s funeral.

“He sees it as the last time people of all backgrounds came together,” Markonish said, when they came to celebrate the life of an athlete and an activist. The name comes from a song — keep these dreams burning.

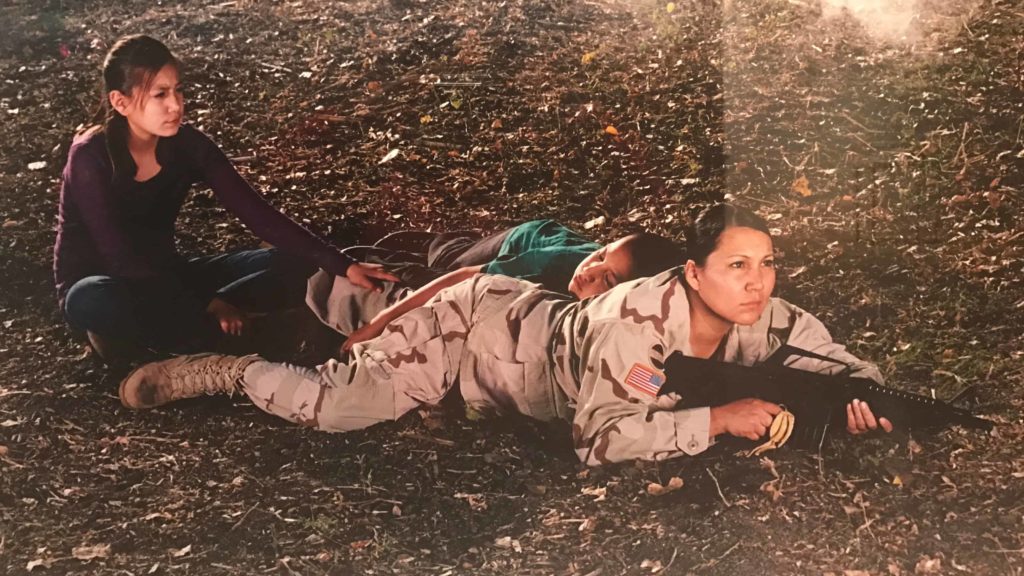

Jennifer Karady creates a portrait of U.S. military veteran Shelby Webster and her family, in Suffering from Realness at Mass MoCA.

Where do we stand

Under gunfire, Shelby Webster remembered the scent of burning cedar.

She tells her story in words and images in a neighboring gallery; she served with the U.S. Army in Iraq, and she remembers one night, driving a truck in a convoy at 2 a.m., seeing explosions — lying prone behind the trucks in the noise of bullets. She thought of her young children at home.

“I’m Native American, and I believe in my culture,” she says in an account beside her photograph. “I believe in my Omaha ways. I said a little prayer to myself asking God to protect me and watch over my babies if something were to happen to me. This feeling came over me, and I don’t know if it was my subconscious …”

She heard her grandfather’s voice telling her it would be all right, and she smelled cedar. At home, her people pray with cedar, she said. She lay on the shaking ground, and she could see and hear tracer rounds and explosions, and she held onto that calm.

Beside her story, a photograph shows a woman in uniform in a field of rough ground. She is lying prone with a rifle, and two young girls press close, holding on to her. A heavy truck is parked behind them in the field, and a man stands near a simple brazier, an iron pot set on an upturned log, releasing smoke. His eyes are closed, and he wears a long scarf or stole and holds something like a feather or a cloth in one hand, as though he is praying with the scent of the smoke and the wind around him.

Jennifer Karady has worked with Webster to tell this story and recorded this image. Karady created the photographs in this show with veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan, Markonish said.

She talks with them about their experiences, not necessarily on the battlefield, but often here in the U.S. as they see the affect their service has on them and on their families. Karady helps them to re-create moments of tension and anxiety. She builds each image like a film set and shows these photographs along with their accounts.

Staying alive

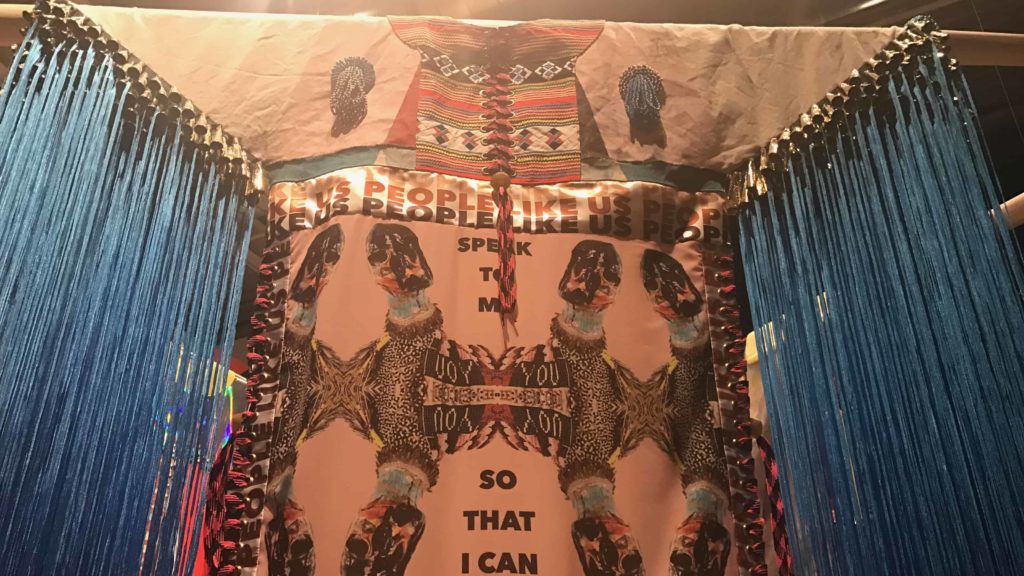

In brilliant colors, Jeffrey Gibson, invokes warriors. A Choctaw and Cherokee artist, he has created long shirts, brightly colored and fringed. They invoke garments Lakota traditionally wear for the Ghost Dance, Markonish said, and they carry also a suggestion of disco because, growing up as a young, gay Native American, he discovered the dance floor as the one place where he could feel like himself.

He invests warriors’ shirts with the language of drag queens and current events, she said. One refers to Bears Ears, a National Monument the current administration has tried to diminish in size.

It is a place of buttes, red rock and juniper forests, high plateau and plentiful artifacts,

and the Navajo Nation, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, the Hopi Nation and others are closely bound to this land.

Another declares, “speak to me so that I can understand you,” the kind of sentence that can come out flat and hard and contemptuous — or can be genuine.

The artist Cassells set themselves on fire to create this film installation, showing in Suffering from Realness at Mass MoCA.

How do you rise up

“You destroy everything special I make,” Joey Farso heard her younger son say to her older son. That lament made her think about the world her sons would grow up in, Markonish said. Farso brought her sons into her studio to build together. They made new work, and and some they knocked down together.

Out of that playful soul-searching come black and white paintings like simple mental machines for listening and thinking. She explores her own body and her experience in surviving breast cancer, and she dedicates a work to Joan of Arc — who was burned at the stake.

And on that thought, Markonish walks into the final room of the show to see a living artist on fire.

Cassells is a transgender activist, Markonish explained, and they often create work with their own body. Here, they have worked with film and stunt experts — and set themselves alight.

The actual burn lasted 14 seconds, and the artist wore protective gel and full-body gear. But the film lasts 14 minutes.

“It’s a Hollywood stunt,” Markonish said, “but it’s still real and dangerous. You think of the fight they have had to go through, to be that determined.”

As she watches, she thinks of monks who have immolated themselves in protest, but Cassells will come out of the flames alive.

They stand in the light with their arms out and slightly bent and their hands open, like a Buddha forming a mudra — like a phoenix with spread wings.

This story first ran in the Hill Country Observer in the spring. My thanks to editor Fred Daley.