It’s a quiet fall evening, and a couple are waiting for their son to come home on a college break. He is catching up with friends, and in the house where he grew up, Anna is putting the rice on to cook and thinking about texting him again. Roj is watching the end of the basketball game and teasing her not to worry.

Their living room could be in any city neighborhood, with the lamp by the couch and the barbecue grill outside the window. They could live on any street with sidewalks and hardy trees, and houses close enough to see the neighbors in light of their own windows.

But tonight someone will knock at the door. A young woman in a sweatshirt and an old backpack comes asking for refuge. And she is flying for her life. In America in a not very distant future, a new underground railroad has formed to help Muslim Americans, in Brent Askari’s American Underground, opening Oct. 2 at Barrington Stage Company.

Askari describes his new play as part thriller, at the end of a rehearsal at BSC’s space on North Street. But for him this possible future feels very close.

The idea of a new resistance network, like the ones that saved Jewish families in Eastern Europe, has come to him as he has heard more and more openly hostile public speech against Arab Americans and Muslim Americans. Askari lives in Portland, Maine He is Persian American. His father came to America from Iran, and his father is Muslim, though Brent is not.

“Especially before the 2016 election,” he said, “I had a lot of nightmare scenarios. Because who is being talked about? They are my family. My relations. If this happens, what can we do?”

People have made themselves afraid, he said. When you make someone into an ‘other,’ everything associated with them seems scary. Ordinary and friendly parts of daily life feel threatening to people who don’t understand them. Listening to music, or even saying hello to someone you love — it all seems a part of something huge and looming.

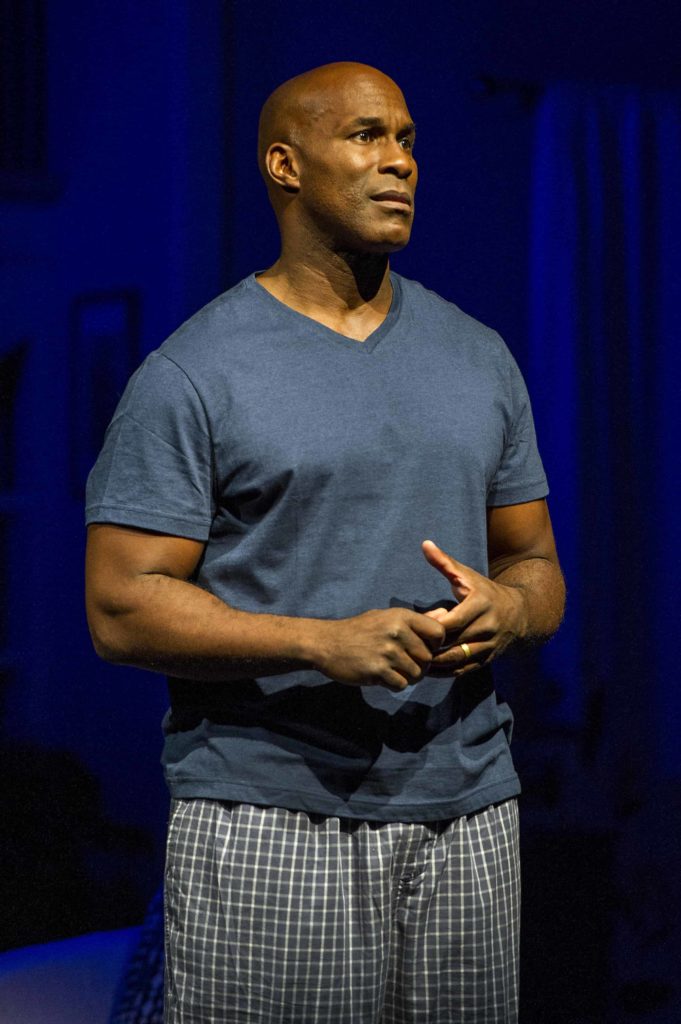

American Underground begins at home, in a place Askari hopes will feel familiar. Roj is a biology professor at the local college, and Anna is a librarian. Their son is a history major. They live with curfews and patrols and a constant level of fear, but they have built family and a place of comfort. In their own house they can talk freely.

Tonight, as their son comes home, two women are about to walk in —a security officer who has lived through her own traumas, and a young woman looking for shelter.

Riders on the underground

Sherri is on the run. She has lost her parents, her brother and her home.

“She’s a true survivor,” Boyd said.

She shows up in a worn dark hoodie

She has always lived here, Askari said. “When they have to move, she says ‘I had to leave the only home I knew.’ She’s American.”

Her friends and experiences, language and school, the games she plays and the movies she has grown up watching all come from a city like this one.

But when she was still a child, her city began to build a neighborhood at the edge of town for Muslims.

“They weren’t talking about it like a ghetto or anything,” she says in the play. “They were actually trying to encourage it, like: Wouldn’t it be nice to be with your own kind? … Some people actually moved in voluntarily.

“Then at some point they decided to build the walls — but of course it was just ‘for protection’ — to protect the people inside the neighborhood from being harassed. It almost made sense, because Muslims were getting harassed. Until the Government decided that they were going to control people coming in or out of the neighborhood …”

So concentration camps get built as though they’re as routine as zoning board meetings. Then the government forces Muslims to move into those neighborhoods. People get rounded up. People in arts and sciences, technology, medicine, in professions and places across the country. Trying to understand this, Boyd said, she thought of Jewish families in Europe in World War II. People who were wealthy and well-educated or working class, in all ages, jobs and walks of life, could lose everything overnight.

Sherri’s family hides to escape the camps. People are getting imprisoned and deported. And it seems to her as though no one notices.

“When we’d leave a park or campground or something,” she says, “and then we’d emerge into society to get our groceries or whatever, it was life just went on,” she says. “… People going to superhero movies, to McDonalds and Applebee’s, eating hamburgers and drinking Coke, smiling and laughing like nothing was happening.”

The new resistance

It turns out that people are paying attention. People like Roj and Anna and Jeff are working to help Sherri. Roj and Anna believe the Network so strongly they will risk their lives, Boyd said.

They each have deep reason. Roj’s family came to New England on the underground railroad, not so many generations ago. And the new Network is sending Arab Americans south, Askari said, back down routes like the one Anna’s parents traveled north from South America to make a home here.

But all the people helping Sherri are invisible.

They have to be, Askari said. Even when they are organized into an international network, they can’t act openly without risking themselves and everyone they are trying to protect. So Sherri can only see the few who have helped her. People in the Network will only know a few people they work with — so they can’t put more people in danger or be forced to give them away.

Askari thought about World War II as he wrote. He learned about people working in the resistance in France or the Netherlands, he said, in countries the Germans had occupied.

“I have a friend whose father was hidden in the Netherlands in the Second World War,” he said, “and some of what he says is here.”

How it felt to keep hidden in a tight space. How it felt to keep still and silent with danger a few feet away. What he did to pass the time.

In a near future

Askari finds this kind of fear and tension repeating through history, and the alternate universe he imagines in this play is rooted in real events.

“This is science fiction based on things that happened,” he said. “And they are happening in China now.”

China has already established ‘re-education camps’ for Muslims, Boyd agreed. “(That idea) only has to cross the ocean.”

The U.S. has used tactics like the ones Askari describes in the play many times in its short history: rounding up people based on their background or culture, race or religion. Forcing them to leave their homes. Isolating them. Imprisoning them with poor food and housing, cement floors, no protection from heat or cold. Boyd finds clear comparisons in the government’s actions against immigrants near the Mexican border, in her director’s notes.

In his fictional future, Askari wrestles with this country’s past and present.

What kind of future does Sherri have? Or the security agent’s niece (or her friends)

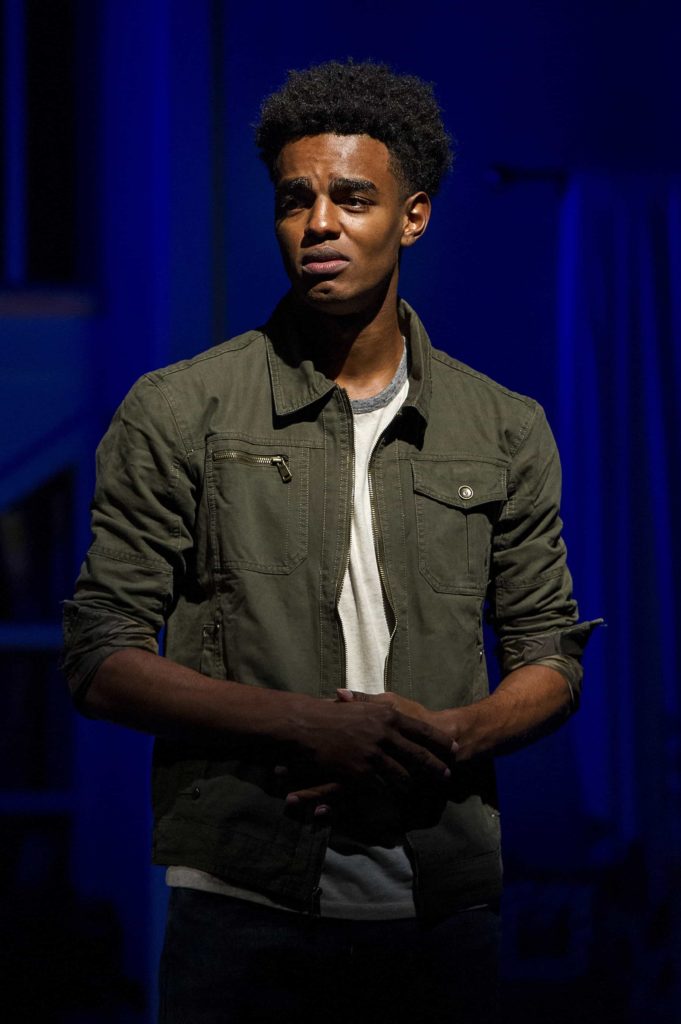

— or Jeff coming home from college? He is not quite an adult and yet not a kid, Askari said. His parents want him to have a childhood, and they want him to have room to grow. They want him to have freedom, and they want him to be safe.

And he is growing into adulthood in a world where he can go to the mall with friends and see a display vilifying ‘traitors’ — and these ‘traitors’ are people who are trying to help Arab or Muslim Americans. Jeff’s friends start cheering on the exhibit and ranting against the people in it, pretending to hit them. They can rant like this and think it’s as ordinary as eating Cinnabons, Askari said.

Jeff wants to argue with them — he wants to shout his disagreements just as publicly. But he already knows that malls have people watching and security cameras. Talking in public can be dangerous.

He has already had friends injured by patrols and friends taken away from school. And these stories are hardly science fiction at all.

As the actors leave rehearsal, they are talking about a recent news story from south Florida, where the play is set: A six-year-old acted up in class, the school called the police and the police put her in handcuffs.