A young woman is standing on the tarmac with a suitcase on wheels. She’s excited and on edge. She’s here in a college summer, after months of planning, and she’s talking into a cellphone, telling her uncle she’s landed. She’s coming to visit her mother’s family, for the first time since she was a child.

Her grandmother left the island generations ago, and her parents are dubious. But she has been studying her grandmother’s country, and she is coming to an annual event to commemorate the thousands of Haitian people who died in a massacre along the border in 1937. And she is coming to reckon with her own family’s past.

It’s a humid summer night, in a break between storms, when Cindy de la Cruz steps on stage in Border of Lights by Guadalís Del Carmen, opening the first week of Celebrating the Black Radical Imagination at Williamstown Theatre Festival.

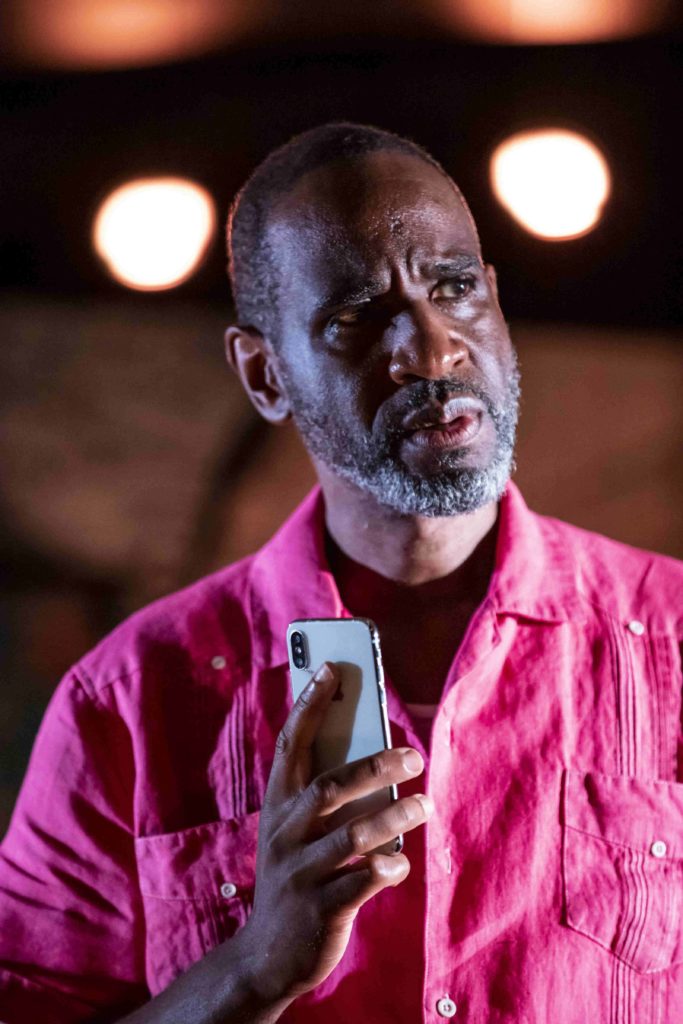

Cindy De La Cruz performs as a young woman returning to the Dominican Republic in Border of Lights by Guadalís Del Carmen. Photo courtesy of Williamstown Theatre Festival.

Nine playwrights, nine actors have come together to create this festival of solo plays, and I’ve been waiting for them. They’re creating new work, and when they talk with me, they give me a sense of intense and fervent creativity.

They walk into the summer night with vivid people and strong feeling, joy and anger, passion and sadness, and limitless invention. They’re looking around the world and around the solar system, into the past and into the future. And I’m thankful.

Tonight we’re all outdoors with the night sounds around us. The set is minimal … a scrim with the feel of a map. The stage crew give the standard introduction (please silence your cell phones) in four languages. I know just enough to guess Spanish, French, Patois, and it’s a comfort. They’re talking to an audience as wide as the playwrights and the actors, and broader.

Celebrate on in. If you want to make some noise — make some noise!

Then de la Cruz walks on carrying all the props she’ll need in one small hold-all, and she’s holding the stage by herself. She’s tall and lithe in a saffron shirt and crimson skirt, a red and gold scarf over long braids.

She is returning to the Dominican Republic, director Colette Robert explained to me.

Rafael Trujillo ruled the DR as a dictator from 1930 to 1961, and in 1937he and his army incited attacks on thousands of people along what had been a historically friendly border — with machetes.

The narrator in the play has just begun to learn this history. She is excited to come back to the island and the family farm she can barely remember. She is mourning her grandmother, and she is frustrated that her parents don’t seem to understand why she wants to make this trip. When she tried to tell them about her plans, back home, her father defended Trujillo, and her mother silently washed dishes.

Now she’s here, on a tropical Caribbean island, and she’s heading inland into farming country. The cab ride takes three hours. She is talking with the driver in Andalusian Spanish inflected with Taíno and Arawak, and Bantu and more African languages.

Her great-aunt is kind. The farm is smaller than she remembers, and they lost the donkey years ago, but she remembers the kitchen where they hold each other and talk. And then she sits down with box of photographs and a tape recorder. Her great-grandfather had been in the army as a young man He had been in Trujillo’s army. In 1937. And afterward, his daughter had interviewed him.

de la cruz looks out at us, shaking. Her grandmother had to hear this story from her own father. And he had to live with it. History can hurt. And the only thing she can do, in an unfamiliar place that is and isn’t home, is to find a way to face it.

It isn’t the first time tonight that a character will have to bear something unbearable. And yet one of the moments that hit me hardest came when she turned to walk off-stage and the next actor came on. They turned and looked at each other. They held each other’s eyes.

A woman holding a candle in anguish for the Haitian men and women who died at the border, looks across the stage at a Haitian man in Brooklyn who had to leave home. She is in her 20s, coming back to the island her where grandparents were born. He is in his 70s, and his children have never been to the island he still thinks of as home.

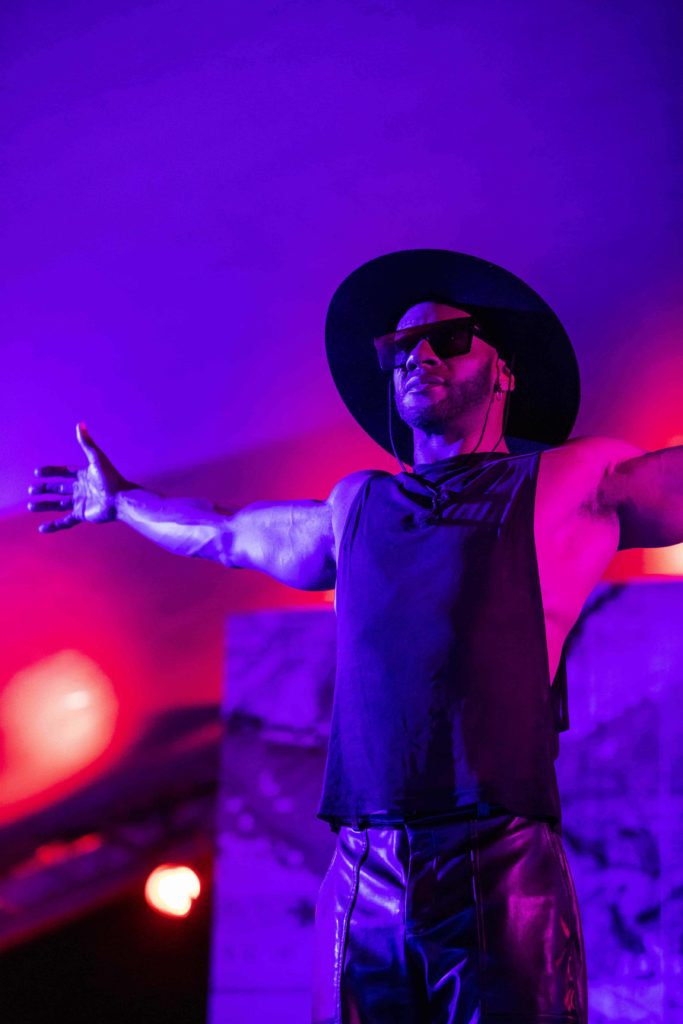

Brian D. Coats performs as Michel in France-Luce Benson’s Ghosts of the Diaspora. He’s a warm, blunt man who has traveled the world to wind up here, in Brooklyn. He speaks with deep knowledge and dry humor. He tells stories of the years when he lived in the Congo — when Black intellectuals gathered there from around the world — when he heard James Brown perform to a crowd of thousands, and everyone was dancing — mes amis!

But tonight he’s grappling with a phone call. His oldest friend could be in danger. They grew up together as brothers … they have not seen each other in 50 years. And the story gets harder. A man does not leave his home and his family, and not come back, without a devastating reason.

Gradually he lets the memories come. He’s in Haiti, and the sounds are around him, women laughing together, neighbors walking to the market and meeting in the streets at night … the scents of the place, coconut, salt water.

He’s telling his brothers stories about the loup-garou to scare them at night. In French, that’s a were-wolf, but in his stories it’s a shape-shifter, a snatcher at night — a threat that can appear any time, anywhere, through any door. His brothers were much younger, he says. He would stay up with his mother when they were in bed, sitting on the porch and talking in the dark.

He never knew his father, but he felt his family around him. He was in university in Port-au-Prince and doing his best to care for them. But he was coming of age in the years when Papa Doc Duvalier came to power. People could be disappeared without warning. Violence could break lives without a thought. The loup-garou could be real.

Roberts finds home and freedom woven into all three stories tonight. All three playwrights are working independently, she said, and they are exploring similar questions. What does it mean to leave home? What wounds do you carry? What does it mean to look for home … and what kinds of confidence, love, human connection can feed your strength …

“All nine playwrights and all of the actors are phenomenal,” she said. “There’s a real community feeling. I’m excited — it’s good to be in person again, to be physical space with other artists and rehearse together.”

Roberts said she has enjoyed this time with the actors and the playwrights. They have all lived in the same house this summer as they worked together here. I think that shared energy comes through for me tonight.

As Michel turns to walk off stage, he sees a younger man walking on — fit, tall, dressed to dance, bringing a bass beat and club lighting with him. And they look each other in the eye. The energy Michel talked about in the James Brown concert he still remembers … it’s coming.

Ashley C. Turner performs Freaky Dee, Baby by NSangou Njikam with unleashed gusto. This third play feels part narrative and part abstract. He may move from a college memory to a tale about an Eagle growing up among buzzards and learning the full extent of his strength — it’s sky time.

He had me sitting up, leaning forward in my chair, calling out loud and laughing. That’s part of the point, he said. Freaky Dee is a character he draws on — he’s a source of confidence and living energy.

Ashley C Turner encourages the audience to embrace life and honesty in Freaky Dee, Baby by NSangou Njikam. Photo courtesy of Williamstown Theatre Festival.

“Freaky Dee is a trickster like Anansi,” Roberts said.

Njikam blends Yoruban folklore and hip hop culture, she said, in a call for freedom — individual freedom and freedom for a whole people. Talking over the play with her, he told her about traditions in Yoruba festivals.

“NSangou talked about an Epa mask,” she said. “(It has a) double-sidedness. We see one side, then another.”

And I think I can feel a double side to the music and the moves, the comedy and the sly haiku. Running through them like a current, I can sense the challenges he is facing. We see the woman who abandons him and the pressures heavy on him. The world asks him to be honest and then turns away. Freaky Dee is a call for response — and change. He says I will prosper you a future. And God, for everyone tonight, I hope so.