Eartha Kitt is singing a teasing folk song she learned in Istanbul, humming with an edge of laughter. And then she drops her voice low and adamant, and she is a mother on a warm night, laying a hand on the forehead of her sick child.

She could be performing a concert out of the 1960s — but we are not where we expect. Its the year 2043, in the future, and it is a complex and raw and beautiful place.

This summer, a group of nationally acclaimed and emerging Black playwrights, actors and directors will explore worlds past, present and future, in Celebrating the Black Radical Imagination: Nine Solo Plays at Williamstown Theatre Festival. In three new works each week, for three weeks, they will travel in space and time, from a moon of Mars to Haiti, to Brooklyn on a summer night.

Playwright Terry Guest honors Eartha Kitt in A Ghost in Satin. She is an international star — a cabaret singer in Paris, Grammy-nominated musician in America, television celebrity, activist against the Viet Nam war, performer in 10 languages — or is she?

“In a futuristic world, you are coming into a performance of this Eartha Kitt ‘ghost,’” he said.”

In this world, science and the entertainment industry have evolved the technology to encode a kind of AI from human DNA. The white scientists who have patented it call it “the closest you can get to real life without a time machine.”

They think they have made a construct, a robot, a hologram, he said — an almost real program with a kind of consciousness. But the demonstration doesn’t go as they expect.

Director Wardell Julius Clark offered the the idea of Afrofuturism to the playwrights he works with in the second week of the festival. He invited the three playwrights he will direct, he said, artists he admires as among the best in his home city of Chicago and in American theatre. Guest joined J. Nicole Brooks and Ike Holter in imagining the future, and they came back with vastly different and overlappingly similar worlds.

Director Colette Robert shared her own excitement in working with writers and actors for the first week, July 6 to 10, some familiar and some new to her, in stories exploring freedom and folklore and home.

She has known playwright France-Luce Benson’s work for years, she said. They have both worked with the Ensemble Studio Theatre in New York, and she has seen Benson’s plays there. She finds them warm and deep with heart and humor, and that same spirit draws her to the central character in the play they are working on here together, Ghosts of the Diaspora.

Michel is in his 70s, sharing an evening in Brooklyn with the audience. He is full of life and energy, Benson said. He tells stories from his travels and adventures, he loves music, he’ll get up to dance … and underneath, he carries the grief of having to leave his home, his mother, his brothers.

He left Haiti close to 50 years ago.

“He represents the experience that many immigrants share,” Benson said. “The longing for home never goes away. Even if they had to leave for difficult reasons, home is home. As an immigrant myself, have witnessed it in family and people I’ve known. A longing for home never goes away. Black Americans, Black people of the diaspora are missing a piece we all walk around without, a disconnect from our homeland.”

“In his family, he is the survivor,” Robert said.

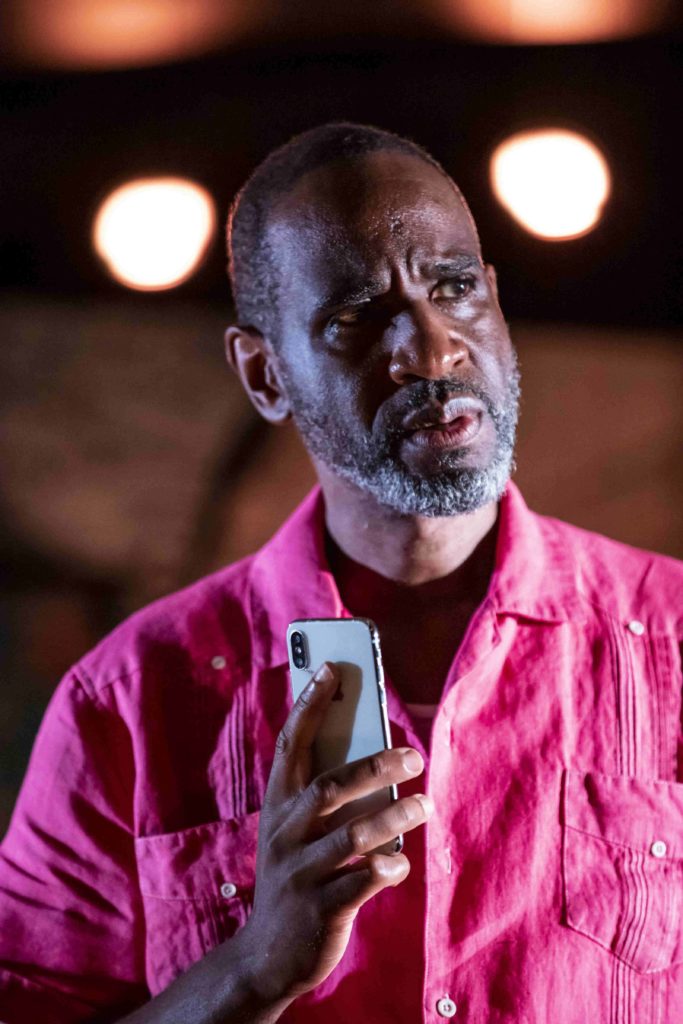

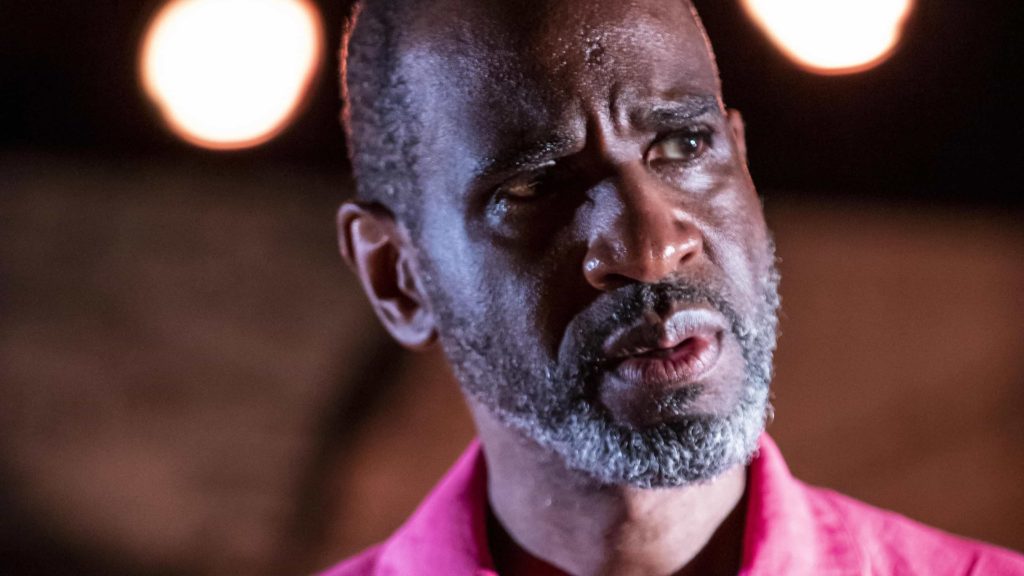

Brian D. Coats performs as Michel, recalling his childhood in Haiti, in Ghosts of the Diaspora by France-Luce Benson. Photo courtesy of Williamstown Theatre Festival.

When we meet him, he is in crisis, she said. He has just heard deeply hard news about a man who was once his closest friend — a man he has not seen in 50 years.

They had grown up together.

“Michel calls Alec his brother,” she said, and in Haiti, that is not a word people use lightly.

Michel’s mother took Alec in when he and Michel were boys, and he and Michel grew up together. She has had to raise her children alone. She was working to support them as a single mother.

“This is a community where people looked out for each other,” Benson said, “and education is very important. It’s a way out.”

Michel was a student at the university in Port au Prince with his brothers, as their father had been. And then ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier overthrew the government, and a few years of reforms gave way in a reign of terror.

Michel left home for Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where president Mobutu Sese Seko was gathering a community of Black, educated, French-speaking graduates and professionals, from many parts of the world.

“He talks about what a magical time that was,” she said. “It was a metropolis, a place where black intellectuals and professionals came together, doctors and lawyers and educators.”

He remembers a music festival in 1974 when James Brown and B.B. King together with performers from the Congo and more than 80,000 people. He remembers a sense of possibility and freedom, prosperity and joy

“At first, he thought it might be a place where he could restart,” Robert said.

But seeking home and finding home becomes more complicated for him — it becomes a lifelong search.

In the pandemic, Benson said, she has been thinking about the idea of home.

“I’ve been thinking about my father’s life,” she said, “and how many places he had traveled and lived in — he was very accomplished, and he lived a remarkable life. And he always wanted to go back to Haiti. It was his dream, and he was never able to realize it. Michel and his story took over, but that DNA is still in the play — being displaced and disconnected and not able to return.”

Ashley C Turner encourages the audience to embrace life and honesty in Freaky Dee, Baby by NSangou Njikam. Photo courtesy of Williamstown Theatre Festival.

Guest found his inspiration in a tribute to Billie Holliday.

“I saw Lady Day, and I loved it,” he said.

He was surrounded by a mostly white audience, and the actor playing Lady Day was taking about addiction and the abuse she suffered as a child, and the audience was enthralled, even excited. It was disturbing to him. What does it mean, he asked, to turn a woman’s life and pain into entertainment?

He sees the technology for it already evolving.

“We’ve had a Whitney Houston hologram tour,” he said, “and Maria Callas performing with a live orchestra. They’re making a movie with the AI tech to re-create James Dean in the lead role. You can imagine some producer wanting Judy Garland to star in a film without having to worry that she will be ‘undependable.’”

What does it mean to live in a world where everything is for sale — image, voice, ideas, history? How would his fictional group of scientists try to ‘program’ someone’s soul?

“(I am asking) questions about what we censure,” he said, “and what we as black artists have to endure.”

And he offers his own real tribute to a woman he admires.

“I idolize Eartha Kitt,” he said, “and her story has yet to be told on any large scale. She’s someone who could not be the person she was without everything that happened in her life — vulnerability and excitement. Any time she was on stage, she had to be making a conscious decision to allow the audience to experience that (truth). That can be rewarding — that can be powerful.”

Cindy De La Cruz performs as a young woman returning to the Dominican Republic in Border of Lights by Guadalís Del Carmen. Photo courtesy of Williamstown Theatre Festival.

He values having the space to create his own work in his own way, he said, as mischievous and honest a work a he wanted to dream. He has been thinking through what it means to be a young black artist trying to create vulnerable work, the most valuable work he can offer, knowing that white audiences, board members, artistic leaders will see it.

“There’s an impulse not to be vulnerable, to protect yourself,” he said, “and then your work suffers.”

Among the group of actors and writers and directors here, he has found space to stretch himself freely.

“The black artists working in these shows have already carved out space of our own,” Guest said. “On Juneteenth we hung out together. We’re building our own family. I will carry that with me. The artists make this place special.”

Clark too feels a power in bringing these stories together.

“This is celebratory work,” he said. “It’s necessary work. And we have an incredible variety. Blackness is not a monolith.”

In American society, in global society, across the diaspora, he sees a rich range and depth — many people, cultures and languages, dreams and loves, and in these plays he sees a representation of some vibrant part of them.

He celebrates the women at the heart of all three stories in his performance.

“We as a culture understand that a Black woman was the first person on the planet,” he said, “and if we follow in her path we can find a better way forward.”

Black are women often the most disrespected, and he seeks to highlight their strength and perseverance, their power and challenge and magic.

“All three plays use direct address,” he said. “We are asking the audience to engage on a level we haven’t been used to before the pandemic — sit up, lean in, get comfortable with being uncomfortable.”

“Don’t be afraid to ask some big questions of yourself,” Guest said. “It may be surprising … and I hope people will embrace it.”

This story first ran in the Berkshire Eagle in July 2021 — my thanks to Jennifer Huberdeau and Kevin Moran.