Rhythm is in the backdrop of our everyday lives — in the pulse rushing through our bodies, the sound of our feet striking the earth, the cadence of our words. Insistent and universal, rhythm is the language of Step — a percussive dance genre rooted in an African American history of resistance.

Stepping uses synchronized, complex body movements, clapping, and vocal play to create a striking visual and musical performance. The steppers’ rhythmic footwork and arm movements are precisely coordinated to create a powerful, energetic drive.

Maxine Lyle is a Williams College alumna, the founder of Soul Steps, and a professional dancer, choreographer, and producer who specializes in Step and African dance. This year, Lyle is bringing the music and history of step to life on the dramatic stage at Williams in her project, Step Show: The Musical—a play that features step choreography, rap, spoken word, song, musical instruments, and narrative. The show, which will begin this week with a public discussion and step workshop on Friday, October 23rd, encompasses step as a central character, exploring the stories and meaning behind the popular dance style.

For Lyle, this show is an opportunity to give step the recognition she feels it deserves in the professional world of dance, while showcasing the history of step within the African diaspora. “I wanted to tell stories that would bring light to the history of step and the meaning behind it for people,” she said, “how it taps into this history of survival for black people and community building for black people in the face of resistance.”

‘[Step] speaks to a resilience among people of the African diaspora and it speaks to a need to connect—a longevity in our blood line, that we can pass it down from one generation to the next.’ – Maxine Lyle

Step draws from many African traditions of dance and began to appear in the U.S. among enslaved African Americans as early as the 1600s. When African American slaves were forbidden to use drums, they used their bodies to create the same rhythms.

Step can also be traced back to its early African roots in South African Gumboot dancing. In the late 1800s, Lyle explained, many South Africans worked as miners in oppressive conditions and were not allowed to speak to one another while they worked. They “developed a code through rhythm” and communicated with one another by hitting the sides of their boots.

“Many of us who step believe that that’s the early connection to what we do now, and I like to think of it as a dance of social resistance,” Lyle said. These miners “used the little that they had in order to stay in connection with one another through rhythm.”

Modern-day step continued this legacy of social resistance when it formally emerged in the early 1900s in the U.S. on Historically Black Colleges in African American fraternities and sororities. Step performances became a powerful component of Black Greek life, as black students carved out space on campuses, tapping into the idea of rhythm as a tool for defiance and unity.

Lyle seeks to showcase this history of strength in her show. “[Step] speaks to a resilience among people of the African diaspora and it speaks to a need to connect,” she emphasizes, “—a longevity in our blood line, that we can pass it down from one generation to the next.”

Step Show is set on a fictional, historically black campus and follows the protagonist, Monie, as she arrives at college hoping to carry forward her grandfather’s legacy by showing the culture and tradition of step. The show floats between two timelines as Monie’s present-day experiences parallel her grandfather’s time on the same campus. In the show, Monie’s grandfather discovers that a segregated event is being planned on the campus, and, through his black fraternity, uses step as a way to protest.

In the present, when Monie wants to create a Black Lives Matter themed step performance, she has to stand up to white supremacists on campus who are opposed to the show. Monie also faces gender biases as she confronts the gender lines which are traditional in the step community—typically separating the male and female steppers into separate groups.

By using step as the link between these two generations, the show deals with systemic oppression, gender bias, and colorism, as a strong Black woman reclaims her voice through rhythm.

Lyle wanted to recognize the history of black fraternities and the role academia has played as the birthplace of step, by showing step in its heyday on a thriving black campus. “For African American college students, step has always been there,” Lyle explains. “It’s been a source of community-building and connection.”

Lyle’s passion for step began in 1996 during her first year at Williams when she co-founded Sankofa, the college’s step team, with four other women of color.

Having grown up in a predominantly black neighborhood in Newark, New Jersey, she said, moving to Williams was a drastic change for her. Step was a familiar childhood pastime from her neighborhood, and it became a way of forming community. There was “a cultural void that it filled for me personally,” Lyle shares. Step became a lifeline for Lyle—a means of connecting with her home and with other people of color on campus.

She finds step a compelling form of connection because it carries on oral histories. Step groups often pass down certain rhythms from one generation to the next, uniting steppers to their pasts. Lyle has seen this intergenerational connection in Sankofa.

“We created choreography that, for us, was a way of demonstrating our unity on campus as students of color,” Lyle explained. “And now, to go back to campus 20 years later and to see that same choreography performed—to know that generations later there are students who I don’t even know necessarily who are tapping into that same choreography and those same rhythms—I think there’s something special in that oral history or that passing down of art from one generation to the next.”

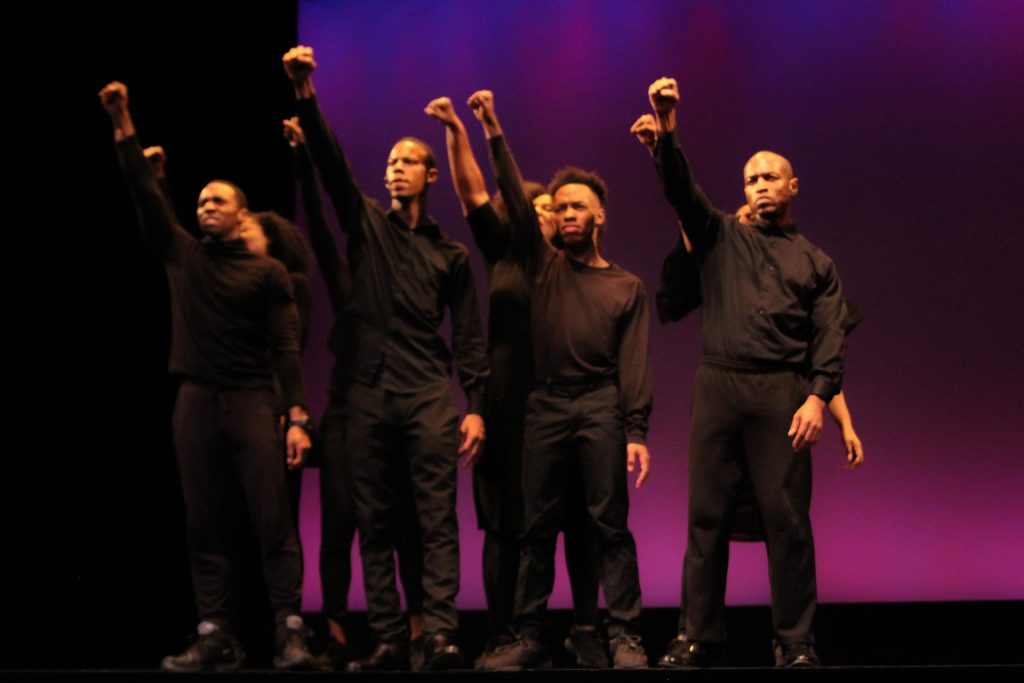

Performers from Soul Step perform in a tradition of African dance and pecussive rhythm. Photo courtesy of Maxine Lyle

Sankofa has changed in many ways over the years, while staying connected to its roots. The group is larger and more diverse than in the past, and, after becoming an official part of the Dance department in 2000, it benefits from greater support and resources. Today’s choreography borrows from its early roots, but is now more complex and elaborate. Sankofa was initially co-ed, and is co-ed today, but it went through a brief phase where the group split in two along gender lines.

In black fraternity life, step is traditionally not co-ed—a theme which Lyle explores in Step Show—but she is glad to see that the group is one cohesive unit again.

Lyle says she has seen firsthand the way step impacts the young people she engages with through Soul Step, empowering insecure or shy students, providing a positive outlet to students who have been in trouble for class behavior, and helping others deal with mental health or learning disabilities by giving them a meaningful and accessible form of expression.

“The transformation I’ve witnessed in people when they have Step in their lives is phenomenal,” Lyle said. “It’s just, it’s real.”

Lyle wants to change the way people think about step by showing this impact on the stage.

“[Step is] an artform that you don’t need to pay for — you don’t need ballet shoes, you don’t need tap shoes and you don’t need years of training. It’s just something that you can feel in your body,” she said. “That’s what I want people to have and to hold onto in the story of step.”

After graduating in 2000, Lyle wanted to continue with step, but she didn’t know of other opportunities to pursue it after college so she founded Soul Step—a professional company that gave her a platform to keep performing step and to form a step community. Since founding the company over 15 years ago, she’s been working towards the dream of a step musical.

She began the project by bringing in other writers to collaborate on the script, she said, until a friend and colleague suggested that this was Lyle’s story to tell.

“Whatever story was living in me was the story that only I could pull out onto the page,” Lyle said. She then took on the role of playwright, and the show began to take form. She is now the playwright, choreographer, and composer, and will be collaborating with other musicians, composers, directors, and actors as she continues to develop the show.

There have been many iterations of a developing step musical over the past 15 years, with versions of it appearing in the New York Musical Theater Festival and traveling to the SKENA UP Festival in Kosovo. This current iteration of Step Show is still in the development phase and has been performed as a work-in-progress at Shepherd University and at the Bickford Theater in New Jersey. Last year, after completing a residency at Shepherd University, Lyle began to speak seriously with Williams about the prospect of bringing the show to the Berkshires.

She was eager for the chance to work with her alma mater, collaborate with Sankofa and reconnect with the step group she founded. Initially, she was concerned the pandemic would stop the collaboration but they have found safe ways to move forward and she feels that the timing is right, in light of this year’s protests and conversations about police brutality which resonate with many of the show’s themes.

‘We don’t need words to be connected to one another.’ – Maxine Lyle

Lyle now has a residency at Williams, and she is grateful to the college, she said, for giving her the opportunity and resources to further develop the script, music, and choreography for the show. Step Show will have three different phases at Williams this year, moving from virtual towards in-person events.

This Friday, October 23 at 6 p.m. Lyle and Katori Hall will hold a zoom conversation about their experiences as black women in the world of playwriting. Hall is an acclaimed Broadway playwright and a friend of Lyle’s.

“We’re going to talk about cultivating characters for the stage and the challenges of being black creatives in the field,” Lyle said.

She and Hall will talk about their writing and performances. After the conversation, Lyle will also lead a step workshop over zoom, to introduce the audience to step moves and choreography.

In February, she plans to have a zoomed event showcasing an in-person step rehearsal as the actors prepare for the show. Then in the spring, as Covid allows, her team of professional actors, singers, and dancers will give a distanced performance of Step Show, incorporating members of Sankofa in the ensemble.

Lyle is constantly working to change the discourse surrounding step. Many people in the art community still think of step as a collegiate pastime, she said, or an activity in youth centers and neighborhoods, but don’t recognize it as a professional dance genre.

This perception has made it difficult for Lyle to find venues, she said, and it has been a challenge to develop a show without adequate resources or budgets — and for a Black show, it has been especially difficult to find support.

“Every opportunity has to be fought for,” she said. “Every door has to be pounded down.”

After her residency at Williams, she hopes she will be able to partner with a regional theater and work towards her dream of getting Step Show on Broadway.

She feels that step has a unique ability to resonate with people all over the world.

“We don’t need words to be connected to one another,” she said. Having travelled and shared step in other countries, she is struck by the way people respond to rhythm across language barriers.

“Rhythm is so universal,” Lyle shares. “There’s something so powerful about the language of rhythm. It can touch people wherever they are. It passes class barriers, and racial and ethnic barriers, and gender barriers — all of that to just touch people in the heart.”