In their voice, words flex, as lithe as a curve of bamboo, as supple as flying at night.

‘… we strangers and sky-walkers

and time-travelers before the rest;

and this becomes what I want of love …’

Micah Rosegrant interweaves prayer and performance and spoken word and creates a form, as they describe it, as close as two people talking at night.

They came to the Berkshires this winter as an artist in residence at the Foundry in West Stockbridge. They found an artistic refuge here, they said, in the time and flexibility and the uniqueness of this space — a black box theater in a village in the mountains, an innovative sound stage, an ice-rimmed stream in the snow.

For a few weeks in a pandemic winter, the residency gave them a space to explore ideas without pressure to perform, and the freedom to create worlds.

They are an actor, playwright and spoken word performer. In the pandemic, people are kept apart, Rosegrant said, and see each other over inorganic technology. Rosegrant is exploring how a trans artist presents themself over a digital medium. They are experimenting with dance, costume, lighting — how the lens of a camera can give a full impression of a wider landscape or a focused impression of a place they can create, like an enclosed world, protected and expansive, fantastic or dreaming or intensely real.

They want to explore the arc their body makes, they said, making space for poems and music close to their heart, art by other queer and trans people of color, and more.

“When the camera is aimed at you, you’d only see the world I’d built,” they said. “What does it mean for you to meet me here? What do I need to communicate to you, form some sort of bond with you, around all that January 2021 was?”

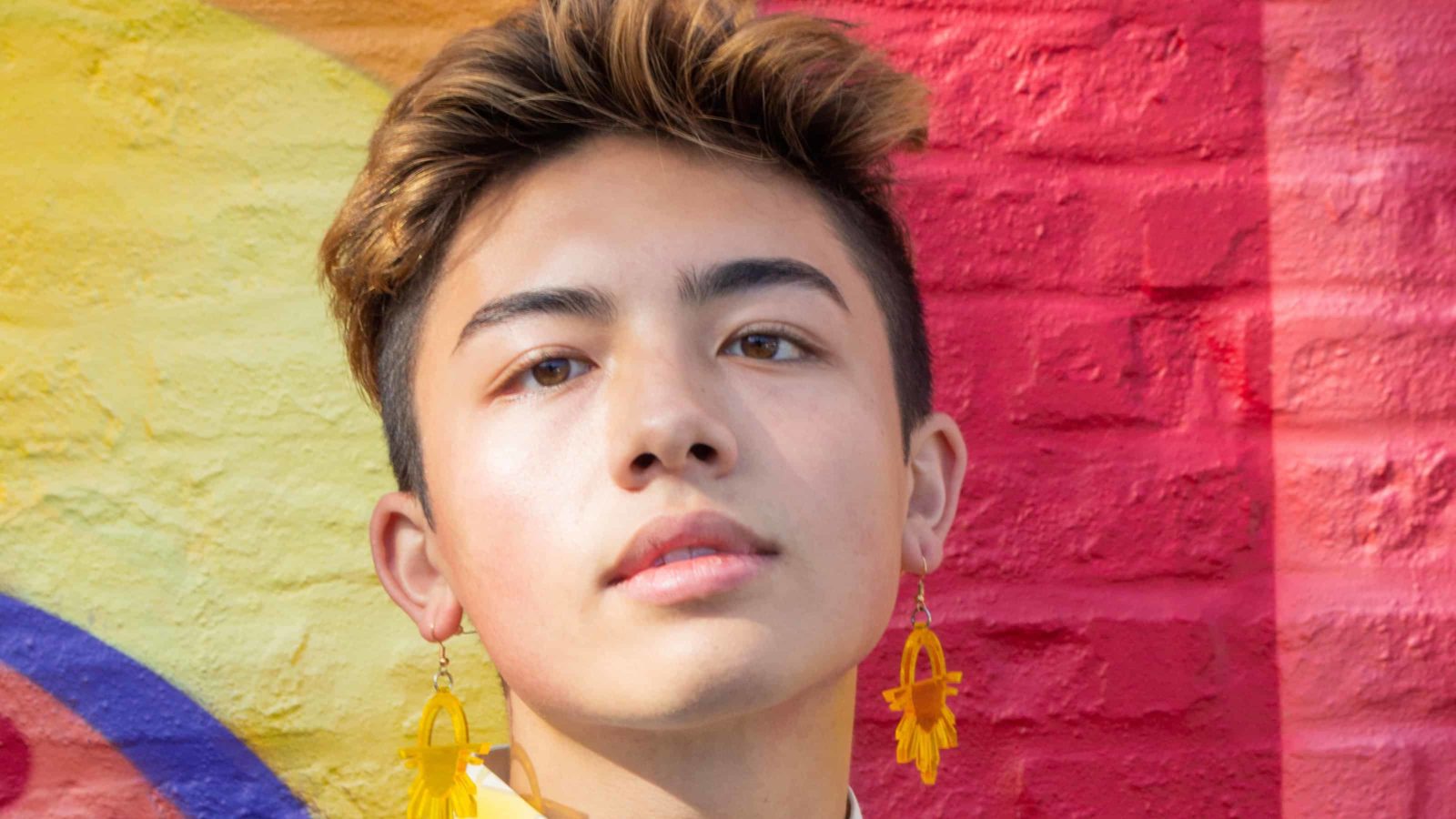

Boston-based actor, poet, playwright and performer Micah Rosegrant comes to the Foundry as an artist in residence. Press phto courtesy of the artist

Those currents of art and community and healing often come together in their work. In Eastern Massachusetts, they are part of a wide network. They are an Artist in Community fellow at Arts Connect International and co-founder of Asian American Theatre Artists of Boston.

Rosegrant created AATAB with friends and fellow theater people as a group to connect Asian American, Pacific Islander American, South West Asian North African, and Kānaka Maoli artists in Boston.

From student potlucks, the group has broadened into downtown performances, staged readings and open mics, community gatherings and conversations with the Boston theater community. Writers and directors, actors and musicians support each other, and throughout Covid they are creating new work together, and they are growing.

‘I’m looking at prayer … as a place for aspiration, science fiction, a place where our lives are no longer deemed as sin. I’m using prayer to unshame our selves and our future. We have so many innate possibilities.’ — Micah Rosegrant

Rosegrant too is creating new work in their senior year at Boston University. In September they performed The First Pineapple and Other Folktales, outdoors in a festival series in Starlight Square. This solo show looks closely into how they perform as a queer person with intersecting identities, they said, Asian, Tagalog, White, and how that body is asked to perform on stage. They are perceived through many lenses, they said, from friendly to outright hateful.

“In America we live in racialized and gendered bodies, in a time of isolation,” they said. “… (I wanted to focus on ) the precedent that we exist and deserve to exist — not do I exist but what does it mean that I exist.”

It was this performance, as they developed it, that first caught the attention of Amy Brentano, artistic director of the Foundry, and brought Rosegrant to the Berkshires. This winter they have been crafting new digital work, and as the spring semester begins they are creating a senior thesis of prayer poems.

They want to hold what is sacred to them, how they experience faith and the divine, a vivid intensity often woven in with the human and natural world.

“I’m strong when I’m with people,” they said.

They experience divinity in strength, innately and naturally part of them. They can feel it in a connection with friends, talking around a table, sharing a meal. They can feel it in theater spaces, in the energy performers can hold between them, and an actor can hold with people listening. They can feel it on a picnic, sitting in the grass in the shade of a tree wider than they can reach around.

“I’m looking at prayer not as a place for help, though it can be,” they said, “… but as a place for aspiration, science fiction, a place where our lives are no longer deemed as sin. I’m using prayer to unshame our selves and our future. We have so many innate possibilities.”

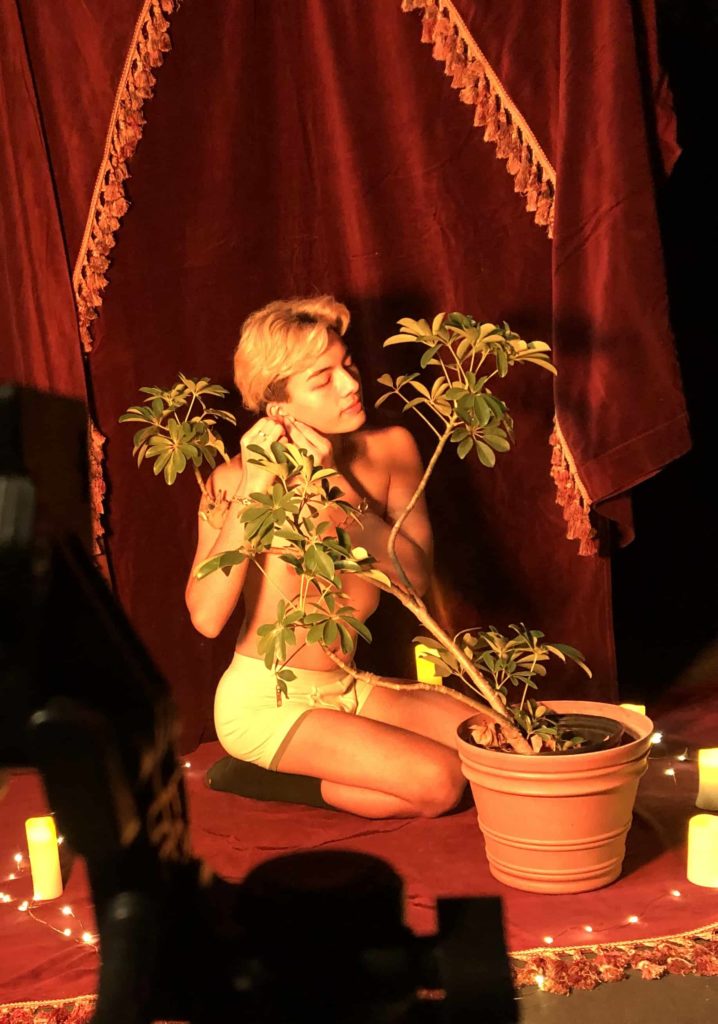

Actor and poet Micah Rosegrant explores themes of prayer, poetry and faith in new work at the Foundry in West Stockbridge. Press photo courtesy of the artist

They want to grow and experience prayer as a sight for queer and trans people of color, they said, people who have experienced oppression. In their experience of it, the Catholic faith does not make a space for them. And so they are creating one, “a place for safe, brave spaces to play with relationships with words and spirit.”

“Can we re-imagine prayer and healing?” they said. “I live in a body words are applied to without my will. Can I re-possess a divinity inherent to me and my community? It was stripped away by prayer I learned growing up.”

The faith Rosegrant learned as a child has shame embedded in it. The relationship with God they learned then was based in subservience and weakness, they said.

That relationship is interwoven with other relationships and histories.

“The way Catholicism met me, through my mother’s side, was through the Spanish conquest,” they said. “She descends from the Tagalog people.”

Her people lived in a wide archipelago south and east of China and Vietnam, north of Indonesia and Australia now called the Philippines from a 16th-century Spanish king.

Before the Spanish came, the Tagalog were matriarchal, Rosegrant said.

“That’s why mother Mary is a primary figure (there now). The Spanish noticed we cared about femininity and the divine feminine.”

Rosegrant looks to a time before that colonial interference, to a strength and tradition rooted for many years in the islands, and feels it sing it in the present.

‘Can we re-imagine prayer and healing? … Can I re-possess a divinity inherent to me and my community?’ — Micah Rosegrant

They draw from the Tagalog tradition of bayoguin. The word comes from a kind of bamboo, and it is the name Tagalog people made for third-gender people. They were katalonan, shamans, healers.

“Bayoguin inhabited roles as spiritual leaders in communities,” Rosegrant said. “What we’d now call cis women were the heads of worship in Tagalog communities, and bayoguin were often among the most powerful people in their communities.”

And so they were among the first targets of conquest. When bayoguin were channeling their gods through their bodies, the Spanish translated their worship as satanic, imposing their culture on a people who already deeply existed.

Rosegrant feels a link to themself in that history, a power that touches them. They perform their own spoken word poetry, their voice warm and rhythmic:

“… One of the terms we made for third-gender people

was the word bayoguin, derived

from a species of bamboo called bayog

that looks like this, bent …

bayog bamboo is beautifully bent

but unbroken from the underbrush …”

“That bamboo poem reminds folks that our relationship to ourselves is innately connected to nature,” they said. “Bayog is a bamboo that bends naturally, and it has uses other bamboo doesn’t have. It’s a unique growth. We are beings of nature, as much as we try to separate from the wild.”

Knowing that the bayoguin lived as a natural part of their communities, as leaders and creative people, moves Rosegrant and gives them a sense of shared ground under foot.

“I wouldn’t claim the name bayoguin,” they said, “as someone centuries removed from that time, but I can re-name it as a way of being. I’m not in touch with the daily realities of their lives then, but I can be in touch with … performing genders, masculine and feminine, as ideas that have transcended time.”

And they can be in touch with creating artwork with the community around them, and with the work of community healing.

“That energy existed,” they said, “and my inhabitance of that fluidity as a means of creating art has deep precedence. (It’s about) getting in right relationship with natural presences. It’s unnatural to think of an artist untethered from where they came from, or as not sensing some sort of medicine in their work.”

Medicine and art are often set apart, they said. And yet medicine is a healing art, an art of life.

“As an artist I don’t label myself as a healer,” they said. “I believe that’s a role the community has to prescribe to you.”

But they see themself as in touch with a tradition of healers … Orishas, doulas, yoga teachers. Humanity has been studying wholeness of mind and body for a long time, they said.

“As a vessel, I can offer this back.”

Actor and poet Micah Rosegrant creates new film work at the Foundry in West Stockbridge. Press photo courtesy of the artist

When knowledge of the past is lost, taken away, they ask how to understand the past imaginatively in the present, as a source of possibility and power. They turn to the writing of Claudia Rankine and Octavia Butler in that struggle.

“Part of that is memory,” they said, “how the memory we have access to can inform our future.”

They recalled Suzan-Lori Parks, the acclaimed American playwright, screenwriter, musician and novelist whose play Topdog/Underdog won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2002 — she wrote of singing to the bones of the ancestors and listening to what they want to tell.

“I’m not trying to authenticate or mystify,” Rosegrant said, “but to echolocate back to (these) sites of violence.”

They feel and recognize losses of the past.

“… One of the deepest violences I’m trying to reckon with in my work is the dismemberment of Lakapati,” they said.

Lakapati is a deity of fertility who moved fluidly between sexes and sexuality — a fertility god and goddess.

“We see this in nature all the time,” Rosegrant said.

Animals, creatures, move between genders, or have the organs of both. In the natural world, gender fluidity is a natural way of living, they said. Many people have respected and revered trans deities, across continents, in Africa and South America, in the Pacific, Hawai’i, Guinea. Many people have had spiritually more inclusion of fluid sexualities and responses to gender. But the Spanish Catholics in the Pacific islands in the 16th century did not.

“They took (Lakapati) apart to implant the idea of the holy spirit,” Rosegrant said. “She was disembodied as a goddess, formed into part of the trinity. It’s why so much of my work takes on a ghostlike quality. I’m trying to rehaunt this place of violence.”

“Catholicism finds ways to penetrate and tear bodies away from people who celebrate them.”

At the same time, Rosegrant feels it is vital to celebrate strengths today and to feel positive change when it comes.

They began to learn more about the traditions of these trans gods and spirits in a semester at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa in spring 2020. They had two months in the islands, they said, before Covid came to bear.

“I learned about that relationship to these divinities,” they said.

It was a rich time for them, bonding with Kānaka Maoli, native people of Hawa’ii, joining in the community there and learning about justice efforts on the islands, and thinking about their life here, in Boston, as someone living in a colonially influenced present in the U.S.

“And the Asian diaspora has its own ties to Hawai’i,” they said.

For them, studying there has been an educational opportunity and a blessing.

“The work I’m doing is part of a huge ancestral tradition,” they said, moving through lives, and time and movements in history and art, more than they can see and touch in a lifetime.

“There’s a joy and a pleasure in knowing I’m a part of it.”

Actor and poet Micah Rosegrant creates new worlds with light and color. Press photo courtesy of the artist

It has become increasingly important to them to find living people who can pass down meaningful knowledge.

“I don’t want to lose sight of the opportunity to connect with the elders in my family,” they said, “to meet them and (understand) historical renderings of their lived experience. … I can learn about the Markos dictatorship from my mother. I can learn from what my Lola, my grandmother, tells me about Japanese times.”

They realize over and again how deeply these historical resonances cycle back into present ideas of conquest and empire.

“Recent experiences of it are the ones we need to address most,” they said. “I don’t think I can address what’s happening in the Philippines and here only through ancestral history.”

They can learn urgent teachings in family stories. When their mother tells them about the year she had her prom cancelled because of martial law, they understand in new ways how dictatorships disempower people, how they strip away dance and social interaction, and what happens when everyone stays home.

When their grandmother remembers the Japanese occupation in the Philippines in World War II, between 1942 and 1945, they see parallels in U.S. policing today.

“I can learn from her and more recent experiences,” they said. “We have to be disentangling this myth that things happen in isolation.”

‘It comes down to — what memories am I making, with what people, and how, and why. I’m reclaiming theater as any time people meet.’ — Micah Rosegrant

It feels increasingly important for them, then, to make art connected with community from its roots — not art for the community, but art with and by and in the community.

AATAB is planning a month of programming with the Philadelphia Asian Performing Artists in March, they said. ACI is launching a cultural equity incubator space and a program of ripple grants, funds for BIPOC artists, offering them resources to meet each other and expand in this time of isolation.

As an artist who has been able to create in the pandemic, Rosegrant feel a responsibility to help other artists find resources. They see both a need and a momentum for art as a tool to lift voices, to connect and strengthen and revive and act.

“Getting curious is how change has to happen,” they said.

And performance can live in all kinds of spaces.

“It comes down to — what memories am I making, with what people, and how, and why,” they said. “I’m reclaiming theater as any time people meet.”

It is one of the most sacred histories of theater, they said, so long ignored in Western traditions — in many parts of the world, theater has long been a space for a community to commune with their gods, a space where deities can come down and speak through their actions.

“By reinhabiting theater as a (literal) and spiritual space,” they said, “we can create opportunities our culture desperately needs, to get in touch with God as something that exists in and between us.”

They imagine that getting-in-touch as an open, uniting movement, with the power of myths that endure across religions and images that have lived for generations. People too often think in division, Rosegrant said, as they divide themselves from the natural world.

“We don’t look at ourselves as belonging, as part, as from,” they said.

And what would that sight look like? Rosegrant wants to think about what it means to feel a tree fall and know it has lived for generations of human lives … or what it means for us to imagine ourselves as beings of flight.

“It’s a river — we have this flowing truth,” they said. “Meeting together, sharing ourselves with each other is divine, tapping into that flow of truth. Where we meet, that’s where possibility starts.”