Take a bright green triangle and give it round green ears, and it becomes an amiable bear. It’s a bright abstraction made of simple shapes, like a picture in a children’s book.

It recalls childhood stories so familiar they seem ageless, and characters out of fairy tales — the wolf, the witch, the giant.

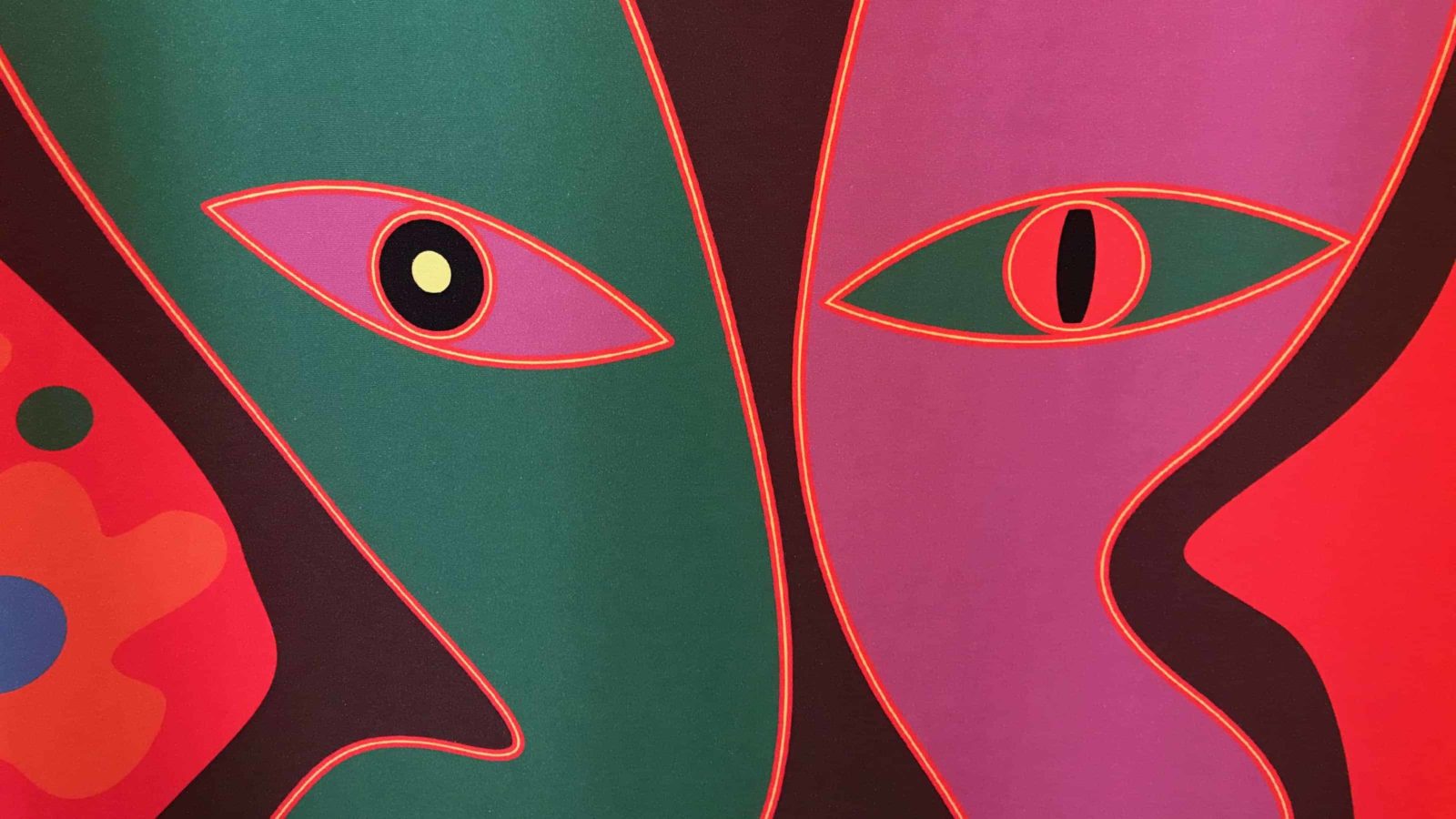

But look again and the bear looks back from half-open eyes. Bright shapes beckon on the walls, living trees and monsters, and they invite questions. What if the witch out listening for owls is good? What if the magic wood is beautiful and not frightening? What if the character telling the story sees from a spider’s eyes?

Argentine artist Ad Minoliti is charging a gallery with the energy of a circus tent or a carnival in Fantasías Modulares, and she walked through it as she prepared to open her installation at Mass MoCA.

Isabel Casso, a graduate student in the Williams College Graduate Program, has curated the solo show. She met Minoliti two years ago in Mexico City, as Minoliti was working on a series of paintings with her mother, Cecelia, for the Galería Agustina Ferreyra.

Minoliti reaches back to colors and shapes familiar in toys and stories, she said, and she stands them on their heads. Casso felt drawn to the brightness and playfulness in her work and has followed her career ever since.

“It’s inviting and fun,” Casso said. “You can have serious conversations in a playful way. … It’s provocative for people coming freshly to the ideas, a light-hearted way to welcome them in.”

Menoliti transforms geometry and abstraction with gentleness and humor.

Abstract art has traditionally been a male discipline, she said. In Modernism, Cubism, Bauhaus artists in many countries — in Latin America, Arte Madí in Buenos Aires and Arte Concreto-Invencíon. And she wants to combat the ingrained contempt for women that has so often come with these forms.

She has created a kind of theatrical scene Casso said, with a backdrop of fairy tale scenery, trees with eyes, geometrical characters made of shapes — a red and yellow cyclops with a freeform almost Cubist body.

It is an egalitarian world, she said. The creatures who live in it are not definably, completely, male or female, animal or human, abstract or fantastic or real.

They can feel as familiar as Saturday morning cartoons. The bear has echoes of Yogi Bear, Menoliti said — though the calm green creature with the quiet gaze could remind anyone looking back that a yogi is an adept in yoga and meditation. And a film playing on a loop creates a collage of backgrounds inspired by Hanna Barbara.

On the screen, creatures meet and merge and exchange elements of themselves, changing shape as they interact with each other.

It draws on ideas from the biologist Lynn Margulies in the 1970s, Minoliti said; she wrote about organisms that survive by fusing instead of competing.

Minoliti wants to take down the barrier between nature and man and machines.

“Nature is as designed and built as any city or urban landscape,” she said.

She wants to rethink the relationship between people and animals, challenge the distinction that people and animals are separate and “that we are superior and we can own them.”

So she invents a joyful magical realist world and beings who are somewhere between human and animal and monster, characters with fluid gender and sexuality. She creates a new fantasy world to change an old one.

Behind familiar fairy tales, she sees a system of morals and values that the storytellers once wanted to teach — but the stories can be centuries old, and so familiar now that people tell them often without thinking of the ideas behind them.

She wants to see those ideas clearly, to play with them and sometimes to challenge them. Children’s stories can teach a discipline, she said. They try to fix people within parameters.

“I want to invite people into a game of creating new narratives, to rethink everything (those stories) told you.”

“(Her work can) take something we might not question in childhood,” Casso agreed, and make it visible. Fairy tales often have rigid gender roles — the woman helpless in the tower, the man fighting fabulous monsters. And they insist on bodies that are right or wrong, normal or ugly, too big or too little or just right. Beautiful maidens almost always have blond hair and blue eyes.

And they often focus on women’s bodies as women walk into threatened areas.

“You have to stay inside the house,” Minoliti agreed.

Science fiction and fantasy often reinforce the same kinds of stereotypes, she said, though some novels break barriers.

Ideas built into children’s stories can continue to shape the way people negotiate the world, Casso said, even in their adult lives. “Should I be afraid of the outside, of the forest?”

“I’m thinking about which are the bodies that count,” Minoliti said, looking around at her figures in a landscape of pink waves, orange hills and yellow skies.

“Children’s drawings are not taken seriously,” she said. “Minorities complain that societies treat us like kids … If we don’t want to be treated like a kid, how badly are we treating our children? In Argentina, we are fighting for sex education in schools, and some religious groups are (pushing back) against those human rights, (against) kids having basic information about their own bodies.”

Her own smarter-than-the-average-bear has a voice in this argument. The green triangle, Minoliti explains, is also a symbol in Argentina of the pro-choice movement. People wear green bandanas in support of reproductive rights.

She imagines a world where people, all people, have authority in their own lives.

In Spanish, she said, the word “cartoons” translates as Fantasías Animadas De Ayer Y Hoy — animated fantasies of yesterday and today.

Here in this room, everyone is welcome.

Up close

What: Ad Minoliti’s Fantasías Modulares

Where: Mass MoCA, 1040 Mass MoCA Way, North Adams

When: Ongoing into 2022

Museum admission: $20 adults, $18 seniors, $12 students, $8 kids (6 to 16), $2 Mass EBT / WIC / Connector Care

Information: 413-662-2111, massmoca.org