A lump of clay feels cool to the touch. The surface is damp enough to slide under your fingers. If you press in, the clay gives and presses back. In downtown North Adams, Oakland, Calif., artist Catherine Monahon is creating an exhibit in clay, glass, wood, wool — and you can touch the art. Listen and the artists will ask you out loud.

Monahon blends storytelling and sound in Conversations with the Material World, an interactive exhibit at MCLA’s Gallery 51, opening tonight at North Adams’ First Friday.

They are here as an artist-in-residence at The Walkaway House in North Adams, they explained as they installed the show in the Art Lab half of the gallery space, alongside the spring MCLA student art show.

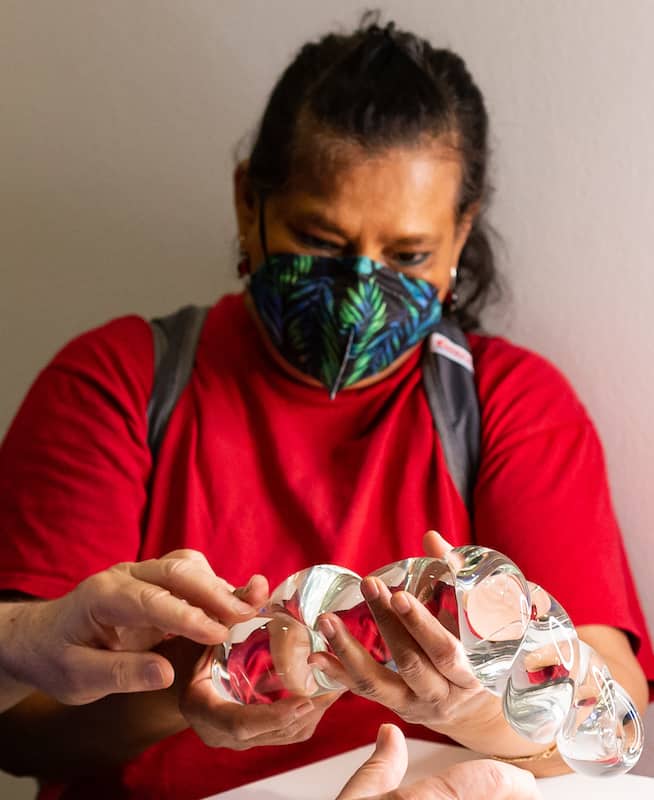

Visitors hold glass to the light in Conversations with the Material World, an interactive art exhibit with sound and contact. Press photo courtesy of Catherine Catherine Monahon

In their Conversations, they have brought together sculptures made of glass, wood, fiber and clay designed by a collective of queer and/or non-binary artists — Monahon and Philadelphia sound designer Lizzy de Lise, San-Francisco furniture designer Dominique Tutwiler, Ohio fiber artist Selena Loomis and New York glassblower Deborah Czeresko.

Monahon comes into the group as a ceramics artist, and they began the show with a question — if they could make something that would give people a sense of how they feel about clay, what would they make?

Talking with artists who have chosen a medium and worked with it for 10 years or more, they asked the same question. Some of the artists Monahon met through their podcast, Material Feels — they talked with Tutwiler in their woodwork studio in San Fransisco. They met Loomis through an artist residency Monahon curated in Freehold, N.Y. and found a shared an interest in pollinators, bees and in beeswax.

‘We’re widening the language of intimacy.’ — Catherine Monahon

With all of the artists, they share a love of working with their hands and a strong sense of touch. And people coming into the space have shared it too, Monahon said. When the show first opened — at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden last summer — the audience’s eagerness surprised them. People were craving physical connection, they said. They wanted to come close to the artwork. And they wanted to share the experience.

“We set up headphone splitters so you could go with a friend, family.”

In the thick of the pandemic, people found the connection powerful, Monahon said. Watching visitors interact with the artwork, they saw a sense of wonder. They would watch as people listened to the voice on the headphones, as the voice asks them to look at their hands, hold the glass up to the light, feel the clay, run a hand over the wood or set a stitch in the patchwork scroll.

‘A voice asks them to look at their hands, hold the glass up to the light, feel the clay, run a hand over the wood or set a stitch in the patchwork scroll.’

They explore also the loss of touch. They remembered especially the day fine artist and writer Elizabeth Jameson came to see the show. Monahon had co-written a piece with Elizabeth Jameson in the New York Times about touch and the loss of it — because Jameson is living with multiple sclerosis.

“When I lost the use of my hands,” Jameson writes, “I lost my love language.”

When Jameson came to see the show, her husband came with her and brought the pieces into her lap so she could feel them.

The art of making can connect with many kinds of relationships, for Monahon — loving relationships with people, “and with the earth, and with yourself, because you engage with the spirit of it and make it come alive.”

“We’re widening the language of intimacy,” they said. “Our culture, Western society, is so narrow in how we see love.”

Visitors hold glass to the light in Conversations with the Material World, an interactive art exhibit with sound and contact. Press photo courtesy of Catherine Catherine Monahon

They ask what happens when someone looks at a cup or a blanket or a chair and sees the hand of the person who made it — and the tree, the sheep, the stone and earth who made it too.

In Monahon’s sculpture, an earthenware shape curves like cup thrown on a wheel and then pulled apart and reshaped. It spirals in like a nautilus shell. They have been working with clay for more than 20 years, they said.

Working with clay means working in motion. On a wheel, clay revolves around the practice of centering, they said. Set the clay firmly on the wheel and then start the wheel spinning. Wet down the surface of the clay so it slides. Rest your forearms and cup the clay in your hands. Bring a light pressure with your fingers, palms, the heels of your hands.

Centering gives Monahon a deep sense of balance, they said — and it holds a paradox. For all of clay’s solidity, if the potter is off-balance, the clay will show it. It may seem odd that one pound of clay can throw off a 150 pound person, but it can.

As a ceramics teacher, they will often teach by setting their hands over a student’s hands to guide them by feel.

“Centering is directly tied to your core and body and mental state,” they said, “and your spiritual state. Your state of mind is crucial.”

‘Centering is directly tied to your core and body and mental state and your spiritual state.’ — Catherine Monahon

Keep the pressure even and steady, and the clay will form a balanced shape. Smooth it into a cone and press down in the center to form a hollow. Let the hollow widen and the sides grow slimmer. You can draw the clay outward or upward … as long as you keep that gentle, patient touch even and steady.

When Monahon talked with each artist, they talked about their hands. Czeresko talked about the signs of her artwork, the burns and scars she carries from glassblowing, and how much she loves them.

In Conversations, she wanted to explore how strong glass can be, Monahon said. She has coiled a length of glass, melted and stretched and twisted like rope. Loomis has hand-dyed fibers, spun yarn, set silk and wool side by side. Tutwiler has challenged themself to make an arch from a board of black walnut, transforming a flat plane into an arc.

‘How someone approaches clay (can so often reveal) how they approach their inner world.’ — Catherine Monahon

Of all these, Monahon finds clay physical and immediate and responsive. They love working with a medium they can touch directly with their hands, they said — not with tools, not with gloves — like touching skin. Even in the language around it, people talk of clay bodies. And the convergence feels natural to them. Clay is made of particles suspended in water, they said, both liquid and solid, like the human body.

In their residency here, Monahon has been exploring origin myths in many cultures, in many parts of the world — haw many have a God who makes people from clay, or a God made from clay. And at the same time they have been reading about scientific experiments replicated in the 20th and 21st centuries suggest that some of the earliest life on earth emerged in clay beds — science and spirituality seem to strike the same note.

They also see and feel a connection between someone’s relationship with clay and their relationship with their own body.

“How someone approaches clay (can so often reveal) how they approach their inner world,” they said.

‘Our hands are one of the most sensitive parts of our bodies — we have something like 3000 neurons in our fingertips.’

When someone learns centering, they have to be in their body, in touch with their body. That experience can be hard, Monahon said, especially for someone who carries experiences of pain in their body, and over time they believe it can be healing.

In this residency they are also researching practices for healing through art, for people living with the effects of trauma. They have found scientific evidence, they said, as well as lived experience of a connection between hands and mind.

“… Using our hands in a dextrous way can relieve depression,” they said, recalling a conversation with a mentor who has taught in the arts for 30 years — and has seen a pattern over that time, as their students seemed to spend less and less time in their daily lives performing deft activities with their hands — activities that people had found everyday and familiar not long ago.

“Our hands are less intelligent,” Monahon said. “… and (they are) one of the most sensitive parts of our bodies — we have something like 3000 neurons in our fingertips.”

They want to give the feeling of sitting next to someone at a pottery wheel with the clay sliding evenly under your hands and their hands resting over yours.

So in this show, in reconnecting people with the feel of yarn, they also hope to reconnect with the act of spinning or sewing or knitting. They are talking about the texture, the scent of lanolin, the tangible pleasure of the wool. And more than that.

The artists are looking into the sustainable nature of a fiber that grows and sheds water and holds warmth in complex ways … and can break down naturally again. And more than that.

They want to give the feeling of hands moving deftly, kneading bread dough, playing an instrument, sliding one loop of wool over another on a wooden needle. And the feeling of sitting next to someone at a pottery wheel with the clay sliding evenly under your hands and their hands resting over yours.