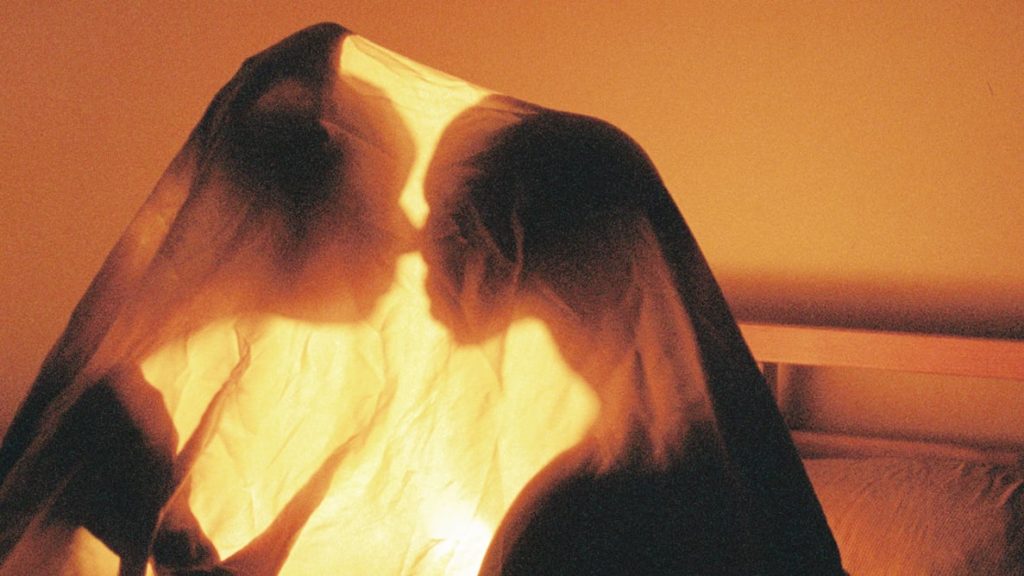

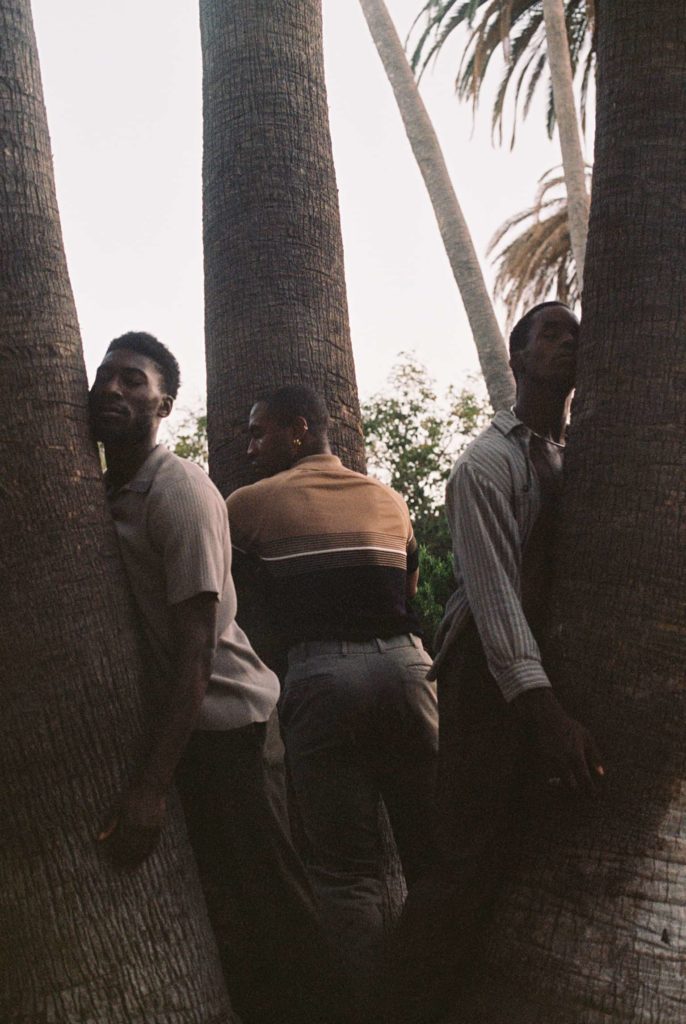

Two men are dancing in the kitchen. They are barefoot, eyes closed, two black men holding each other at home in a quiet lighted room. Los Angeles photographer Clifford Prince King offers an image of refuge and care in Close to You, opening in April at Mass MoCA. In a world that can be hostile and frightening, he and the five artists around him are looking honestly at rejuvenation and renewal.

The show began to take form in March 2020, said curator Nolan Jimbo, a graduate student in art history at Williams College. As the quarantine set in, physical intimacy became precarious, forbidden, impossible. In a year that has amplified fear, division and protest, he is drawn to artists thinking through kinship and intimacy.

He wants to honor a practice of care, he said. The idea of family is deeply human. People give each other a place where they can relax, show fear, give comfort — and strengthen, and create.

Here in this show, queer artists and artists of color find and define and create family, in the absence of the country’s sanction to live and love as they are.

He wants to make this a space for respite. Mass MoCA has often become known for large-scale spectacular projects, he said. He imagines the museum as a sanctuary, a place to feel and share emotion, not only a retreat for knowledge.

“That’s what art has always been for me,” he said.

In his show, six artists from coast to coast look into kinship with friends, with loved ones, with the land, with creative and cultural traditions and with themselves.

It begins for him with Laura Aguilar, a Chicana photographer in Los Angeles who has influenced generations after her.

“She’s at the forefront,” he said. “She’s seminal figure. She has impacted the artists following her, and in last few years her work has been more and more visible.”

She is often known for portraits of people in her community, blunt, hardworking, sometimes laughing, sometimes looking straight into the lens — women couples at a local bar like the photograph that opened Axis Mundi at WCMA in fall 2019.

The body of work in this show comes from a series of black and white self portraits in a desert landscape. The textures of her body blend into the folds of rock and sand and shadow.

“There’s a wholeness in that kind of kinship,” Jimbo said. “It sets the tone for the rest of the exhibition. I looked for a similar frequency.”

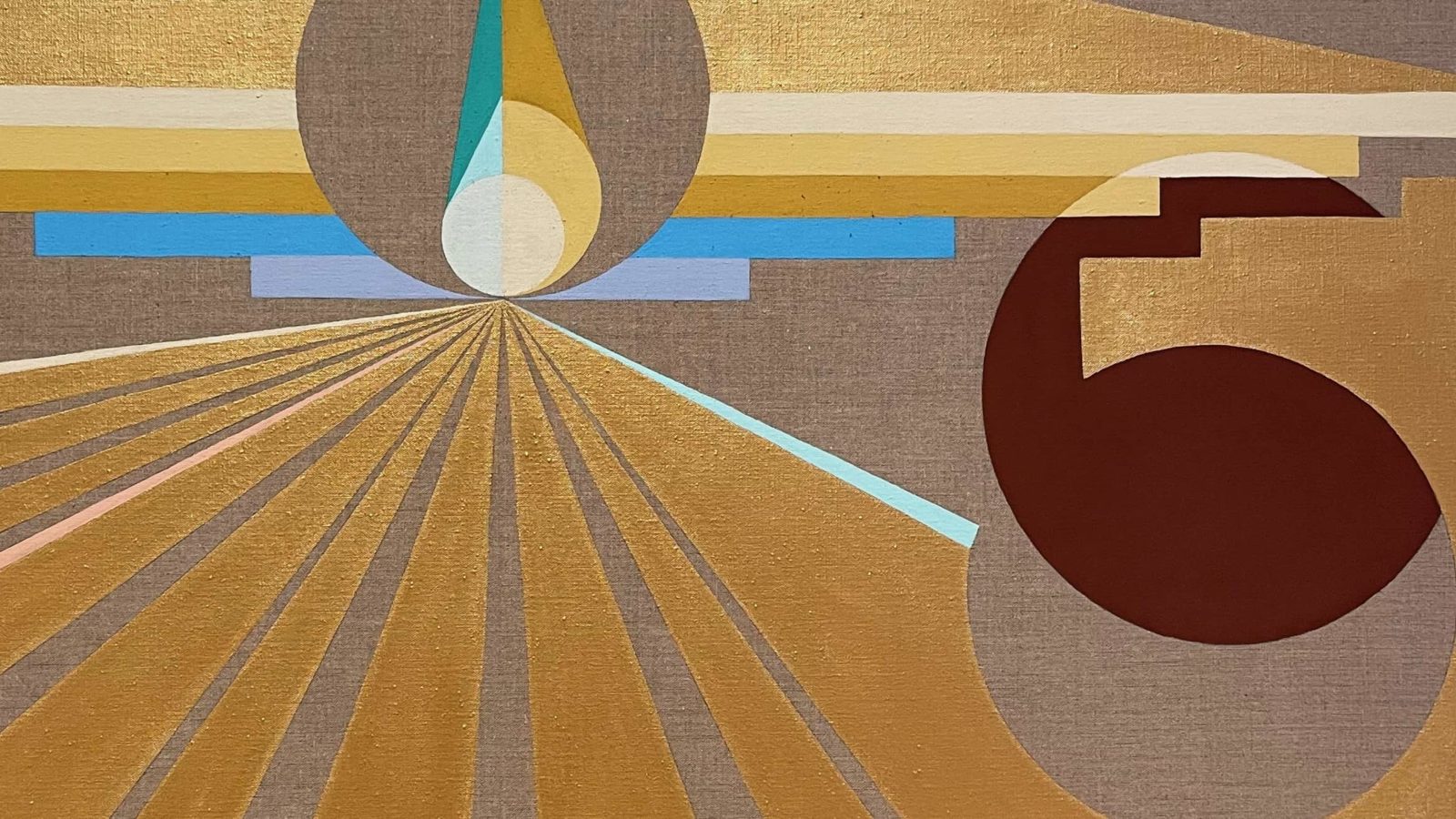

Eamon Ore-Giron's gleaming abstract painting draws connections between artistic traditions across the world.

King too looks into intimacy in daily life. His subjects are often his friends, Jimbo said, and he shows them in quiet, tender moments.

“Rituals and forms of communion are seen throughout my work,” King said by email from L.A., “in order to showcase acts of love, self care and preservation. Whether it’s braiding hair, making meals, dancing in the kitchen, these moments are small acts that allow for myself and other black queer folks to heal, process and overall take care.

“Rituals are routine, but when you step back, slow down, the everyday processes of care are actually very beautiful and inspiring to me. These images are in spaces of refuge.”

He is the only artist they commissioned, Jimbo said. King has eight photographs in this show, and four of them are new. He often brings a group of friends together to make his images, he said, and in Covid, he has found it a challenge to gather. In the last year, in the pandemic, moments of touch have sometimes become rarer and all the more powerful.

“My work relies on closeness, connection and intimacy,” he said, “so I really just took my time and tried to find those moments within my small group and myself.”

One of the photographs is a self portrait reflecting hiself (and the camera) through a mirror as he sits in bed.

“We were all so isolated last year that I looked more toward self portraiture to convey personal kinship and self love,” he said.

For Jimbo, these daily images hold an intent and power. They hold interactions he rarely sees in art or media, stories he rarely hears told. There’s power, he said, in seeing yourself represented. He feels a tension too, in these images where people are gentle and relaxed. They trust each other. They are in places where they feel safe. And even here, they are aware of the camera lens.

“There’s always a sense that his subjects are witholding something,” he said.

He feels them protecting some part of their individuality and interiority. As they are sharing an honest moment with each other, they are shielding some part of themselves from people who look in from outside the scene.

King suggests that feeling is partly intentional. His images welcome anyone, and at the same time they speak in a language that people who share his experiences will know without translation.

“I always try to include some sort of code or nod to queer black community within my work,” King said. “My photographs are for everyone to see and enjoy, but within the images are pieces that can only really be understood by the people who have also inhabited those spaces, or know the sitter within the photographs.

“Photographs capture a singular moment, but my goal is to make viewers curious about the before and after. How did this image come to be? Who is this person? Often I aim to document personal growth, metamorphosis, physically and mentally.”

“I’m hoping these works will have some underlying meaning beyond the image alone. Kind of a ‘if you know, you know’ thing. I think pointing them out will ruin the conversation you can have with the piece for yourself.”

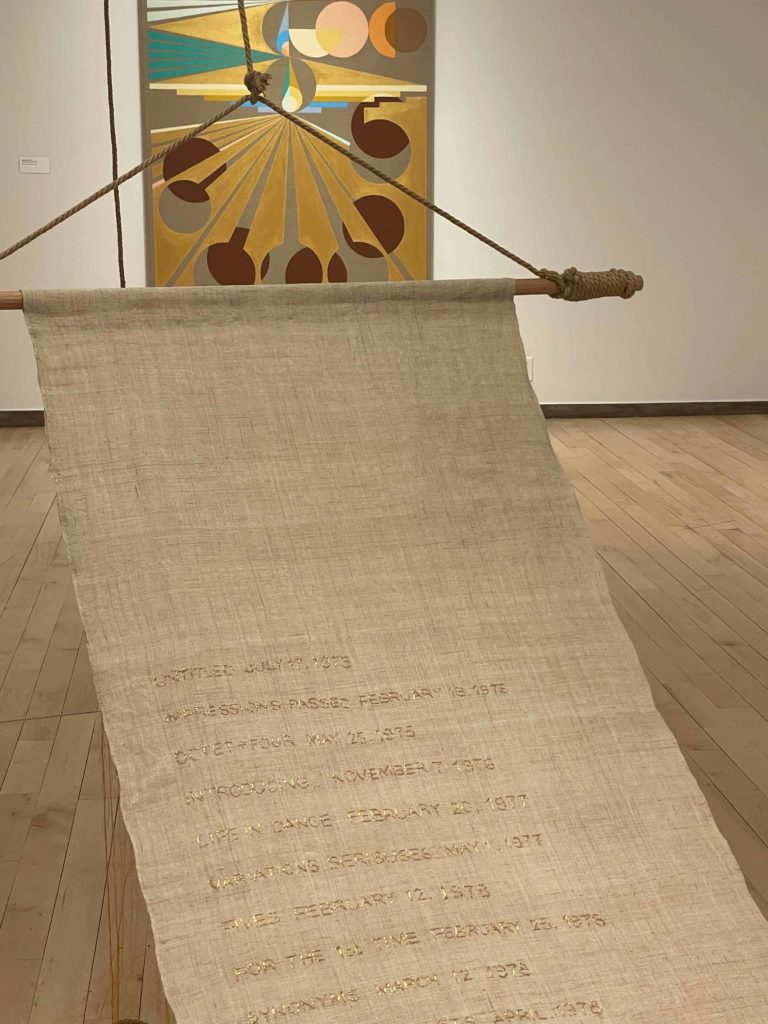

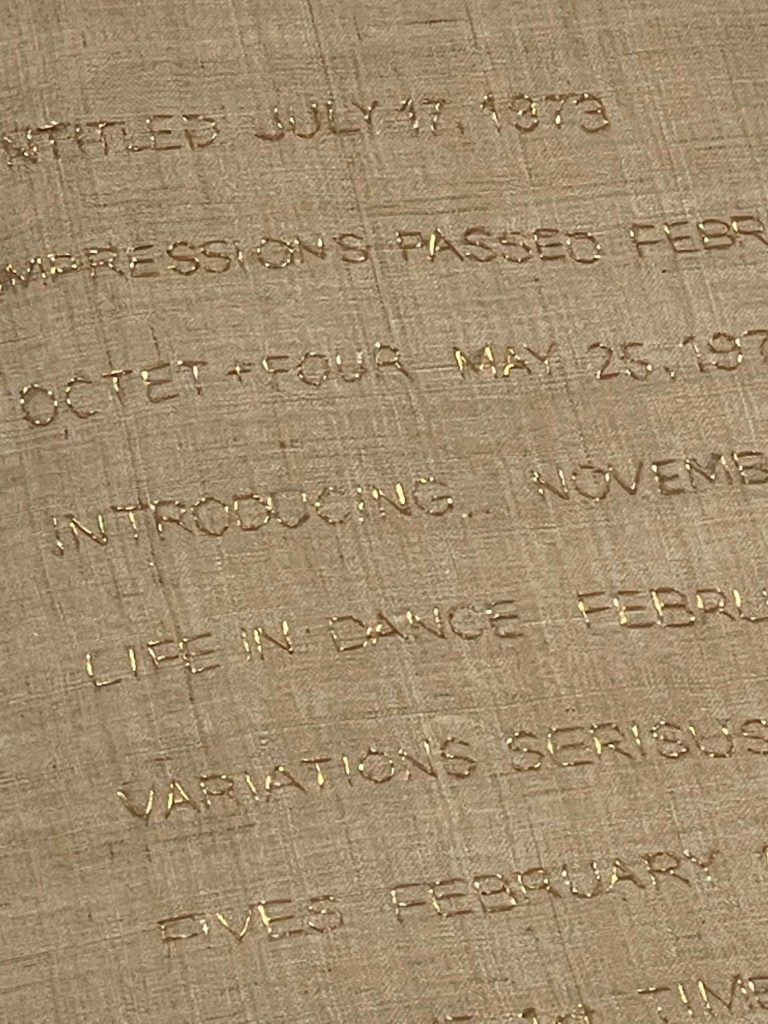

Kang Seung Lee's (Untitled) List, 2018-2019, honors Chinese American choreographer Goh Choo San.

Nearby, in conversation with his work, New York artist Chlöe Bass asks how much connection exists between people at all, in times like these. She has created a film around images of open sky.

“She is challenging limits of kinship,” Jimbo said, “pushing back on assumption that we can share. We experience even the sky differently.”

She created the film in 2017, he said, in politically intense time. As a Black woman, she was working through constant images of police brutality and the ascendency of a political power that based itself in hate and anger.

“Narratives can be invisible,” Jimbo said. “Her experience is unique.”

Finding stories and people who have become invisible, and making them visible, has become central for Kang Seung Lee. A multidisciplinary artist born in South Korea, he now lives and works in L.A.

He imagines kinship as care, Jimbo said, using his art practice to tend to invisible, neglected legacies of queer people of color.

Here he has created a hammock twined with hemp and gold thread as a resting place for the Chinese American choreographer Goh Choo San.

Goh was born in Singapore, Jimbo said, and danced in the U.S. and Asia, before he became ballet choreographer at the Washington Ballet. His choreography crossed the country to the Dance Theater of Harlem and Alvin Ailey. The American Ballet Theatre commissioned his Configurations for Mikhail Baryshnikov.

In his lifetime, he held an international influence. And he died from AIDS in 1987, when he was 39.

“His legacy is neglected in dance legacies,” Jimbo said. “… Kang does a lot of work with archives, looking for scraps of narrative.”

He creates this work in kinship with someone who has passed, Jimbo said, looking to the past. The hammock draws attention to a body missing, the invisibility of a figure within. Kang has made it from sambe, a hemp fiber used in clothing in Korean funerary rituals. It carries the feeling of a memorial.

Small drawings usually accompany the work, he said, figures dancing, facies or parts of their bodies erased, so they are partly represented and partly invisible. They show an erasure of history. Even in their absences, he calls to the body as an archive, recalling Goh as man who loved and rested and lay awake, and the dances he gave life to, the dancers to touched and lifted each other up.