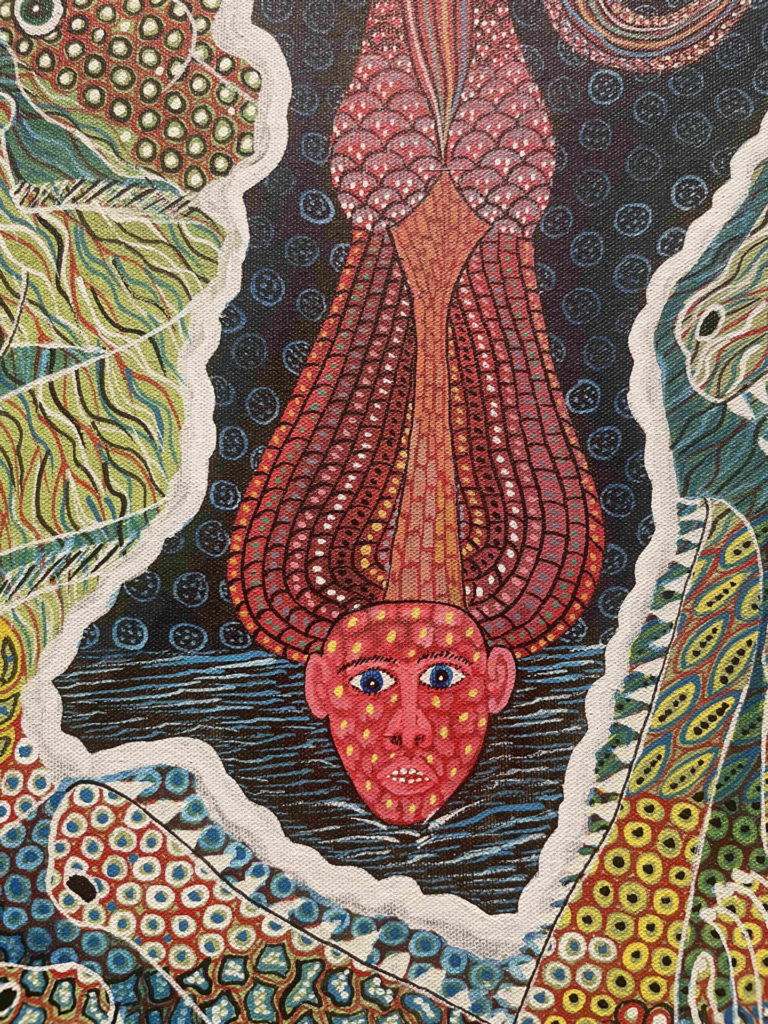

Two beings are moving between water and air — they may be floating on the foam of a wave or hovering over the water in a light like a storm at dawn. They are women and divine. A leaf-green mermaid with translucent wings is lying in the water, looking up into a coil of animals merging and in shared bodies, giraffe and zebra, bird and fish.

Frantz Zéphirin, one of Haiti’s most widely known and internationally respected artists, is painting a transformation. A spirit is changing her form and her mind. She is Erzulie, one of the strongest of the loa, the divine beings in Vodou, in his own faith. And she has more than one form and more than one spirit.

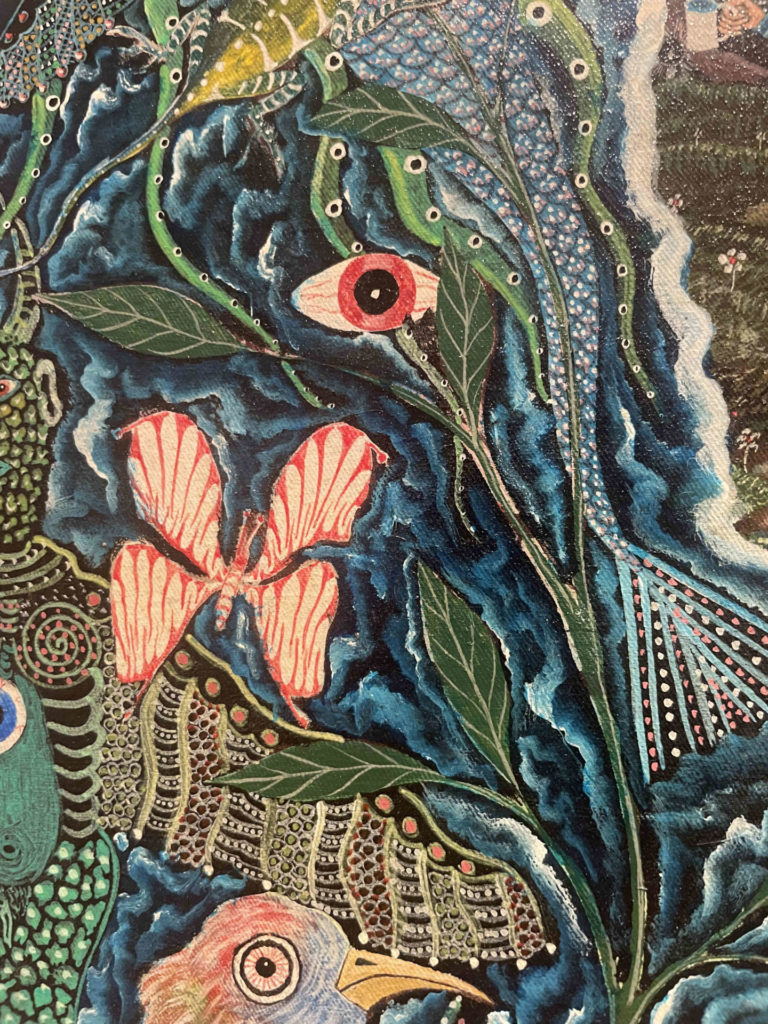

A woman holds up an offering bowl and a lit candle in a wooded dlearing in Frantz Zéphirin's painting, Gran Bwa, as woodland creatures and spirits gather. Press image courtesy of Central Fine.

As Erzulie Freda she embodies love and dancing, a confidant and laughing pleasure. And as Erzulie Dantor, she holds warmth and passion, knowledge and a courage to last through generations — she becomes a protector of single mothers and children, and she can channel the kind of anger that leads to action and freedom.

She’s here, now, looking out from a quiet room in Williamstown on a sunlit afternoon. Tomm El-Saieh, a contemporary artist with growing recognition across the country, has curated a new show of Zéphirin’s works at the Williams College Museum of Art, with WCMA Mellon Curatorial Fellows Jordan Horton and Destinee Filmore.

Zéphirin’s paintings are unique, El-Saieh said, speaking by phone from his house and studio in Miami. — in a long tradition of artwork steeped in the Vodoun faith, no one has shown these spirits as Zéphirin does.

Frantz Zéphirin paints a swirl of divine spirits in Les Mystères de l’Initiation Mystique (Metamorphosis of Erzulie Freda and Erzulie Dantor), 1999, Press image courtesy of Central Fine.

And so the curators sharing in a growing awareness and respect for his paintings, Horton said, walking through the new show on a spring afternoon. Zéphirin’s work has come to Williamstown just as his paintings are representing his country in the Venice Biennale.

‘Frantz’ work looks visionary, psychedelic.’ — Tomm El-Saieh

He paints with a rare intimacy and attention to detail, Horton said, tracing layers in these vividly colorful scenes — myth and storytelling, Zéphirin’s own experiences and spiritual life, and the creatures and trees and birds who live around him in the Caribbean — and often far beyond.

Zéphirin often references his faith, Vodoun practice and divine beings, the Loa, surrounding them with symbols of offerings and rituals. His paintings draw Horton back, over and again, enlivening imagintion.

“You should be able to take what you enjoy and follow it when curiosity strikes,” Horton said.

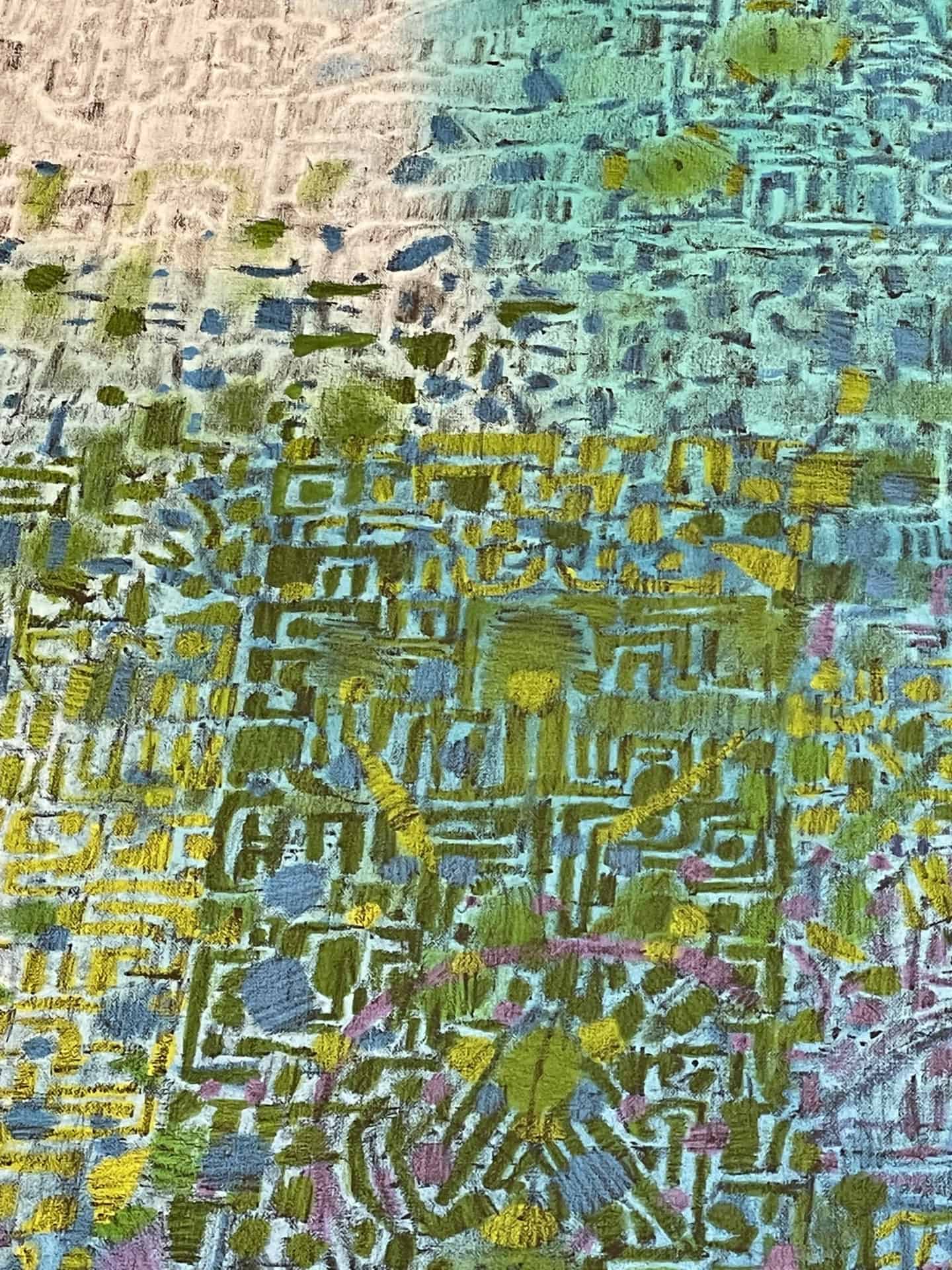

As art fellows, Horton and Filmore have come to know Zéphirin through El-Saieh and his work. He and Zéphirin are friends, Horton said. El-Saieh has four abstract paintings in a solo at the Clark Art Institute now, in a new solo show, Imaginary City, named for a dreamlike, sometimes futuristic theme in Haitian art.

‘You should be able to take what you enjoy and follow it when curiosity strikes.’ — Jordan Horton

When El-Saieh, Horton and Fillmore came together in a collaboration between the Clark and WCMA, El-Saieh introduced them to Zéphirin’s paintings, out of a deep respect for Zéphirin, he said, and a sense of cross-currents between Zéphirin’s work and his own.

Tomm El-Saieh's painting Canapé Vert gleams in green and turquoise, seen close up in Tomm El-Saieh's 'Imaginary City' at the Clark Art Institute. Press image courtesy of the museum

In his own abstract and mazelike color and Zéphirin’s textures, El-Saieh feels the trance-like drumming of a Vodou priest calling to the spirits. Each spirit has their own rhythms, he said, and their own styles of dance, in the ceremonies that honor them. Zéphirin’s paintings seem to move with sunlight on salt water or veined leaves.

“Frantz’ work looks visionary, psychedelic,” he said.

Horton looks closely at the drummers in Gran Bwa (Great wood), drumming wondering who they are calling. Zéphirin shows them through an opening in the trees. A central figure stands in a clearing holding an offering and a lit candle. Eyes are glinting in the leaves, looking out from the wood and from green beings, some partly human and some varied and fluid — fronded or winged or glinting with scales.

Zéphirin paints portals, El-Saieh said, windows into the supernatural. El-Saieh has honed in on that theme as he looked through paintings for this show — Zéphirin is one of Haiti’s most prolific artists.

“He says he has made more than 20,000 paintings,” El-Saieh said.

And many of them draw on themes from his faith. Vodou is a major subject in Haitian art, El-Saieh said. Deeply rooted now, it has grown on the island in the last 500 years, among people who were brought here by force from Africa, or their forebears were. Vodou has some roots in the faith of the Fon people of Dahomey in West Africa, he said, and shares some influences with Santaría, a faith and culture throughout Brazil, Cuba and Trinidad, with connections to the Yoruba in Nigeria.

“There are spirits in Vodou that exist nowhere else in the world,” he said.

‘There are spirits in Vodou that exist nowhere else in the world.’ — Tomm El-Saieh

The faith has grown like an oral history,he said, where one story may become a web of stories as it moves between many tellers. Vodou does limit truth or understanding to a single authentic voice — it has many. Practices can be different from temple to temple.

“Creating your own language and rhythms is a beautiful thing,” he said.

Zéphirin is a Vodou priest himself and spiritual leader, the living in the mountains outside Port-au-Prince (explains the Venice Biennale.)

Haitian artists Tomm El-Saieh and Frantz Zéphirin

Tomm El-Saieh, an abstract artist born in Port-au-Prince and showing his work across the country, brings his own abstract paintings to the Clark Art Institute in a solo show curated by Robert Wiesenberger, associate curator of contemporary projects. El-Saieh is a parner at the artist-run gallery Center Fine in Miami, and he is the curator of a solo show of work by the internationally acclaimed Haitian artist Frantz Zéphirin at the Williams College Museum of Art.

He has taught himself a great deal, El-Saieh said. He started painting when he was a boy. Zéphirin was eight years old, living in Cap-Hatiën, a port town in the north, and selling his paintings to tourists on cruise ships.

He learned from his uncle, the Haitian painter Antoine Obin, El-Saieh said, who painted in a school or tradition from a community of artists in Cap-Hatiën. Antoine had learned from his father, the artist Philomé Obin, who became widely recognized in the 1940s for scenes of daily life, sometimes with elements of magic realism.

But Zéphirin quickly developed his own style, El-Saieh said. He finds Zéphirin’s work completely original. He wanted to show varying forms of Zéphirin’s work in this show, he said. Some of these paintings feel like miniatures to him, striking in their detail.

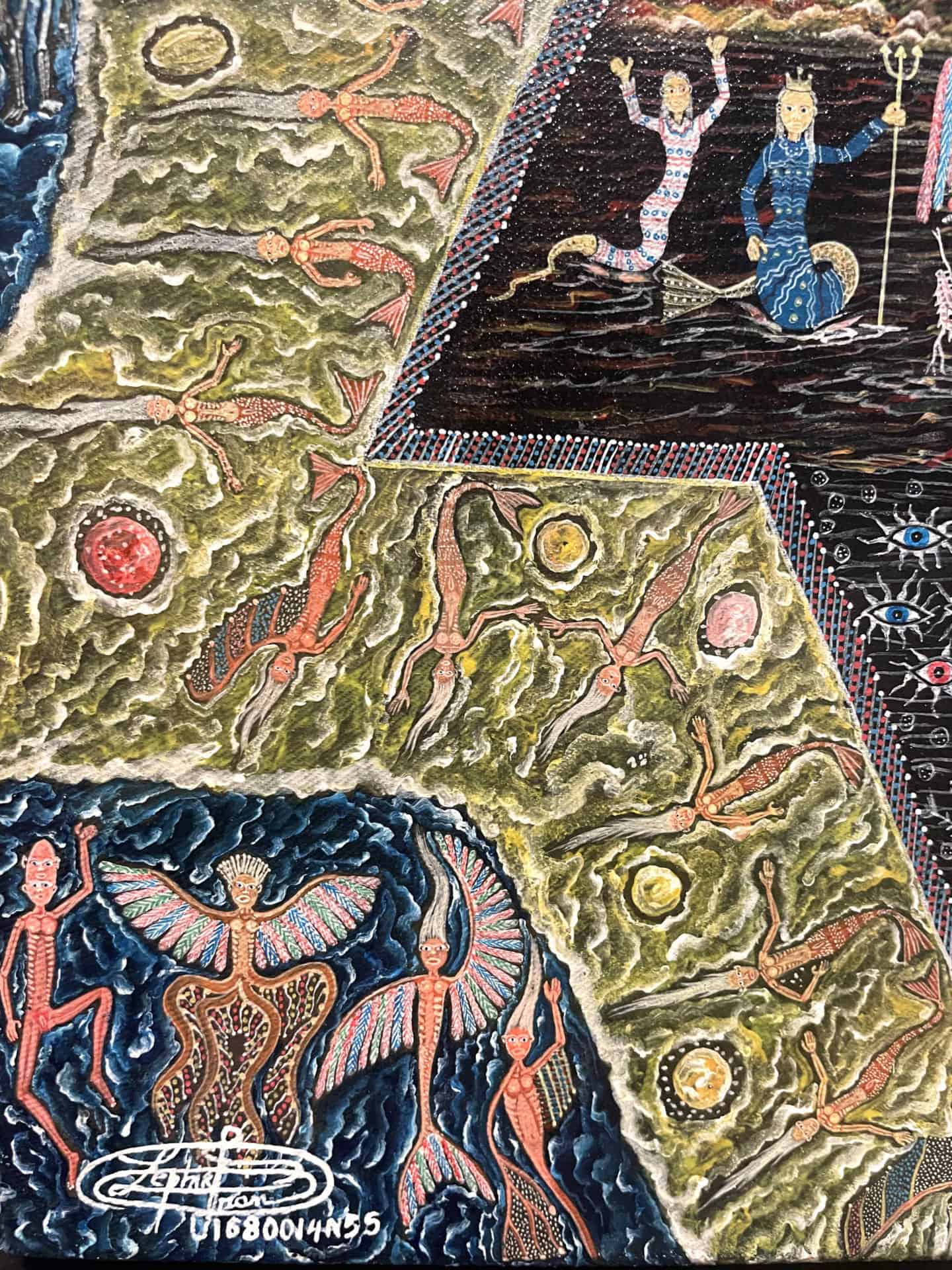

Merfolk surround a six-pointed star in a golden and shimmering border in a choseup of Frantz Zéphirin's painting, Seventh Dimension. Press image courtesy of Central Fine.

They hold a fluid communication between humans, animals and spirits, Horton said. Spirits transform into animals, sometimes into more than one creature at once — long hair swirls into a bird’s head. A woman looks out from many faces. A giraffe with a long arched neck shares a human body spiraling blue and dark and spangled with points of light, like the night sky.

“Look closely,” Zéphirin says in the show, “and in every person there is an animal, a monkey, an elephant, a crocodile, a giraffe… I see them in a gesture, an attitude, a character trait, and immediately fix them on the canvas.”

Spirals often come into the complex patterns he weaves into trees and water and skin.

The spiral became a central symbol in Haitian art and literary movements in the 1960s, El-Saieh said. A new form of art and writing grew in the chaotic years of the regime of ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier — a time when people died or vanished without warning — attacked, kidnapped and disappeared, killed or forced into exile.

“Life is chaotic,” El-Saieh said, “and their artwork is navigating chaos.”

He considered the patterns he sees in Zéphirin’s work as a whole, over time.

“There’s something about ships,” El-Saieh said, “Not far from Cap-Hatiën is the point where Columbus first landed, where the Santa Maria ran aground. And his crew turned the ship into a fortress. It was brought down by the Taínos.”

‘Look closely,and in every person there is an animal, a monkey, an elephant, a crocodile, a giraffe… I see them in a gesture, an attitude, a character trait, and immediately fix them on the canvas.’ — Frantz Zéphirin

The Taínos are the Native people who were living on the island when Columbus landed and attacked. Columbus comes up in Frantz’ work often, El-Saieh said, as he explores the past and the present and the future. Zéphirin’s work at the Venice Biennale deals with colonization and the slave trade. His artwork also appeared on the cover of the New Yorker after the 2010 earthquake.

“His first inclination after that trauma was to paint,” El-Saieh said, “and he started working right away.”

He paints in-between places — at the border of the physical and the spiritual — and in and elements, and the rich variety of living beings he imagines, he offers symbols of a kind of continuity, like the tide.

Planets and astral bodies orbit his metamorphoses. Merfolk float with a rainbow of tentacles for hair, spinning around them in the waves.