Objects carry traces of living stories. Some are old and worn from use, stained with sweat, or caked with mud. Objects can be battered with the recklessness of childhood or lovingly cared for—passed down through generations. Others are set apart, meticulously preserved behind glass and placed on cushions, separated from the touch of tradition, memories, the caress of a familiar hand.

For Wendy Red Star, a nationally recognized Indigenous multimedia artist and curator, it is often strange to encounter objects from her own culture and upbringing in museums.

“It’s so funny to see an Elk-tooth dress, that’s a dress I grew up wearing, and just to see it handled in such a precious manner when I grew up hiking them up to get on a horse and sweating in the hot summer sun and dancing and they were really used, in kind of a hardcore way,” she mused, “and to see the handling of these objects … to see that this is such a utilitarian object to be placed in a cushioned case and handled so out-of-context, it’s weird. It’s surreal I guess.”

On Tuesday night, Mass MoCA and MCLA will host a virtual artist roundtable discussion — Reimagining Care of Indigenous Objects — to explore the ways museums and institutions are shifting their approach to Indigenous collections by placing the authority and expertise in the Indigenous communities.

‘[It’s about Native communities] having access and a connection because that’s the missing half of that object, the story and the living culture of that object’ ~Wendy Red Star

As an artist and guest-curator, Red Star will join artists Tanis S’eiltin and Peter Morin in a virtual tour of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) as they discuss the ways in which museums can better reimagine their care of Indigenous collections to further extend access and authority to Native communities.

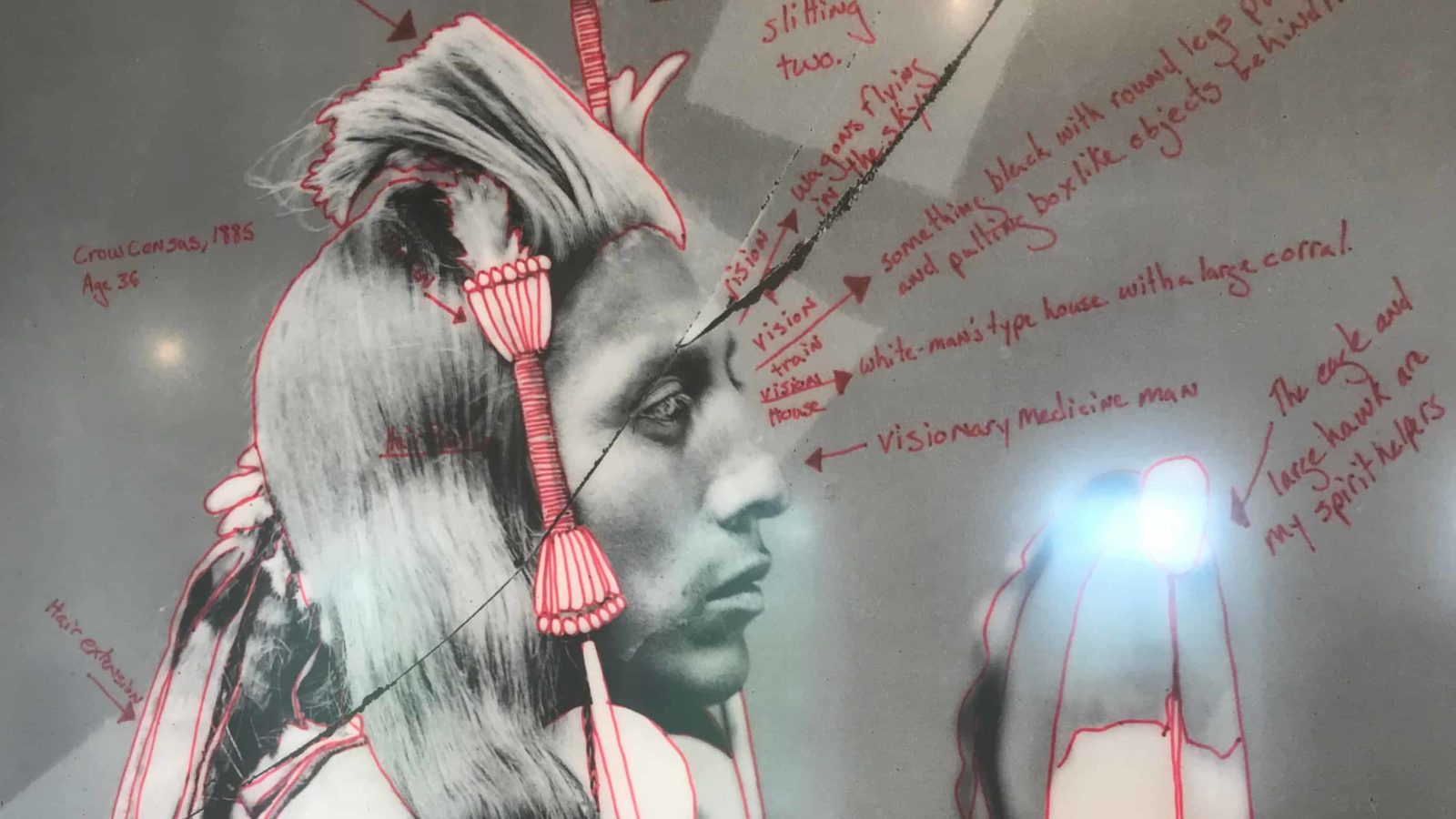

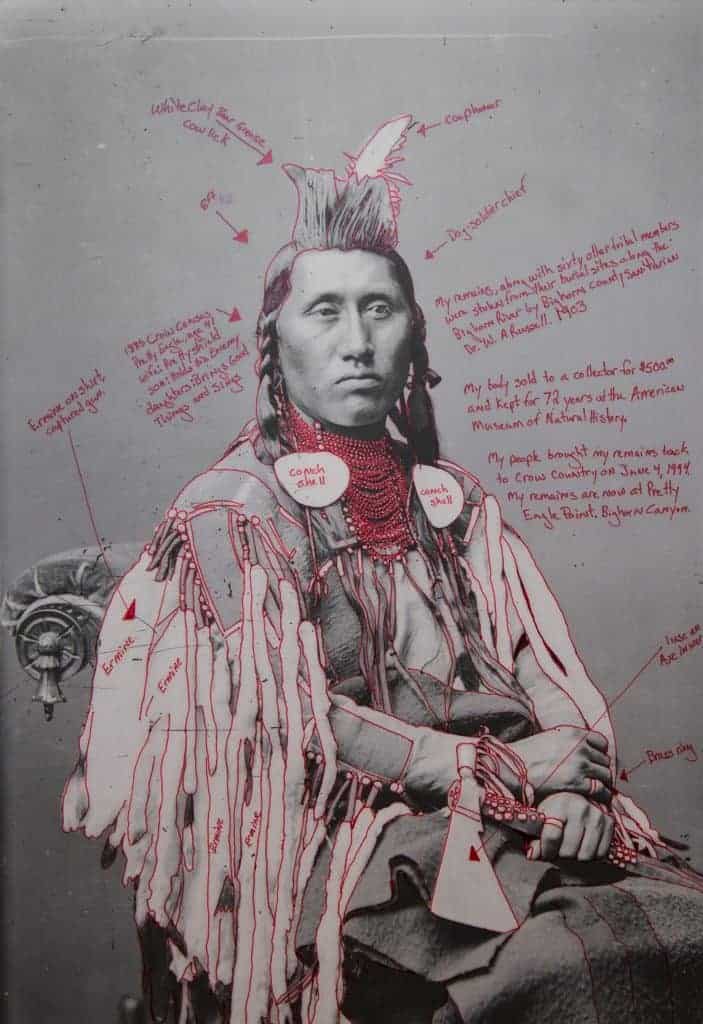

Red Star is a nationally recognized contemporary artist and curator exhibiting her work across the country, and a member of the Apsáalooke (Crow) nation. She draws on historical documentation and Apsáalooke material culture in her artwork. In her exhibit at Mass MoCA, Apsáalooke: Children of the Large-Beaked Bird, she uses historic imagery and cultural artifacts to reexamine the Crow Peace Delegations through annotated portraits.

She has worked with the museum to curate this event, focused on the idea of reconnecting historic objects with their homes.

Red Star is interested in ways museums who have these objects in their collections can reconnect with the Native communities who originally owned the objects. For her, it’s about “[Native communities] having access and a connection, because that’s the missing half of that object, the story and the living culture of that object,” she explained.

She first felt the power of reconnecting with Apsáalooke objects during a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship at NMAI. In her broad earlier experience with museums, she had usually not been allowed to handle any of the objects in the collection, or only occasionally with gloves, but her time with NMAI felt different.

“They let me hold everything with no gloves on, and I got to turn it, and that was profound for me,” Red Star recalled. “The Collections Specialist kept saying, ‘these are your objects’ and I would always kind of give her a wide-eyed look because in other institutions it never felt like they were my objects. There was a barrier there, a big barrier, and I almost felt like I had to be on my best behavior or otherwise I won’t get to see the object, so I’ll do whatever you want me to do, you know? So this was the first experience that I’ve had where I felt a sense of empowerment.”

She hopes this roundtable discussion can invite people into a conversation that’s been lacking.

“It’s just been missing,” she said, “and it’s about really a one-to-one of humanization, I guess, like you’re a person, I’m a person and here’s what happened in my story. It got disrupted, and here’s an opportunity for the institution to stop disrupting and let us sit here and just share, and hopefully everyone has enough empathy to take that away from the conversation,” she emphasized. “It’s a start.”

Déaxitchish / Pretty Eagle looks out of a historic portrait in Wendy Red Star's series, 1880 Crow Peace Delegation. Red Star is a contemporary Indigenous multimedia artist who frequently uses material culture from the Apsáalooke nation in her work. Photo courtesy of the artist.

This roundtable is part of the first module of the Care Syllabus, a new initiative created as a collaboration between Mass MoCA and MCLA which aims to invite “wide experiential conversations about the arts and the humanities and their intersection and relevance in our world today,” explained Levi Prombaum, an art historian, ACLS Fellow at Mass MoCA, and co-director of the Care Syllabus. Prombaum has served as a curatorial assistant at the Guggenheim, involved with exhibits including Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now, and his research explores the enduring inheritances of civil-rights era image making.

Envisioned as a year-long program, the Care Syllabus will bring “six guest curators, each experts in different valences of care and justice-oriented practice across the arts and the humanities,” Prombaum said.

In their opening program, on Tuesday night, Red Star and her fellow artists will consider their own work and objects they have chosen from the NMAI collections.

Red Star believes that Indigenous artists can be conduits — channeling their own history and material traditions in order to create contemporary, relevant work. She draws a sharp contrast to western institutional practices of relegating Native work to the past.

Her work and her ongoing exhibit at Mass MoCA offer an example, as she digs into historical events. She literally draws her ancestral history into the present, taking old photos of men and women, ambassadors and diplomats from the Apsáalooke who came from their homelands, in and beyond what are now Montana and Wyoming, to the U.S. government in Washington, D.C. Red Star writes directly on their portraits, revealing stories in the regalia they wear, honoring their lives and tracing their connection to future generations.

“I feel like the power of being an artist is that we’re creative problem-solvers,” she said, “and I thought that that was one way that we could get together as artists and have these conversations about how our communities can gain access, starting with the arts first.”

The roundtable will gather three contemporary Native artists from different communities — S’eiltin is a member of the Tlingit, and Morin a member of the Tahltan, both in the Pacific Northwest — to speak from their respective traditions. Because NMAI is currently closed to all visitors, the artists have collaborated with Collections Specialist Christine Oricchio to organize a virtual tour of the objects they have chosen. NMAI has more than 800,000 Indigenous objects, according to Red Star — 1200 in the Apsáalooke collection, 3000 Tlingit objects, and 500 from the Tahltan Nation. Each artist read through a list of all the objects from their community in the collection and selected pieces they wanted to see and discuss in the roundtable.

The question of access and care of Indigenous objects can take many forms. Museums, Native artists, and activists have discussed the way museums literally care for or treat certain objects, Native peoples are urging museums to honor the different traditions each community has for the care of sacred objects that are in their collections. When objects that have strong significance, Native activists have called on museums to return them to the Indigenous communities that originally owned them.

In many cases, Red Star said, these communities are not even aware that museums have the objects.

“A majority of my community has no clue that these objects even exist in various collections across the country,” Red Star explained. “Specifically, for my community, our material culture is spread far and wide.”

Red Star hopes that museums will take an active role in transparency and outreach to Native communities.

‘We, as artists, are the conduits and if these historical material cultures are used literally, or if they’re used in the abstract, I think it’s very much part of the contemporary conversation.’ ~Wendy Red Star

Along with increasing Native communities’ access to objects in collections, Red Star feels the U.S. needs a fundamental shift in the way people understand Native authenticity, expertise, and authority.

For centuries, white Americans, museums, and academic institutions have relegated Native people to the past — reinforcing this idea in the language they use, the stories they choose to present and the ways they appear — and making it difficult for Indigenous artists, like Red Star, to carve out space for themselves in the contemporary art world.

“I feel as an Indigenous artist who is a contemporary artist, sometimes the contemporary world defaults us to the natural history world,” Red Star said, laughing. “How powerful is that? That my ancestors’ stuff is in the Natural History museum because they thought of Native people as part of the natural world.”

This tendency to relegate Native people to the past reinforces a larger western view of Native people as extinct or lost. “When you think about Edward Curtis the photographer, his whole mission was to document the vanishing race,” Red Star reflected. Curtis was an American ethnologist at the turn of the 20th century who focused on the American West and Native people. Images like his played into the narrative that Native people were a part of the past — while they are living today across the continent, 6.8 million people in the U.S. and more than 1.6 million in Canada.

“I think (images like Curtis’) really solidified in the western mind that authentic knowledge and Native people exist within this specific time period,” she said, “and everybody else is not authentic anymore, because they’ve been westernized. “We have to get rid of that notion and empower Indigenous communities.”

Because museums have typically not seen contemporary Native groups as authentic, she said, they have not recognized Indigenous communities as sources of knowledge and expertise.

“So many of these state-run institutions that care for Indigenous objects,” Prombaum said, “and so many of these Natural History museums — it wasn’t until the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s that they even formally conceived of Indigenous communities where these objects came from as the bearers of the expertise and the history.

“That’s a relatively recent change in their museum practice,” he said, emphasizing how long it has taken for museums to start recognizing contemporary Native authority.

“It’s just been denied,” Red Star stressed. “It’s always been there; it one hundred percent has always been there.”

She feels that in the current political climate, people of color are raising their voices and hearing them amplified. It is especially difficult for Native people, she said, because they constitute such a small percent of the population, but she feels that people are beginning to listen.

“We have a tiny bit of a voice,” she said, “but I see hope in that.”

Wendy Red Star's Apsáalooke Feminist # 2, 2016 from her Mass MoCA exhibit, Apsáalooke: Children of the Large-Beaked Bird. Installation photograph by Kaelen Burkett.

Local schools are using images from her exhibit in their curriculums, and they have sent her their lesson plans to look over. In this way she is directly using history in her artwork to impact contemporary understandings of Native peoples.

She feels that looking at historical timelines, events, and people in her work grounds her and helps her understand the way the world functions in the present.

“Native history, which is U.S. history, is not taught in schools, and so to me, the past is the contemporary,” Red Star said. “It’s building a solid foundation and a platform so that I can extend that to the next generation. I would say that we, as artists, are the conduits and if these historical material cultures are used literally, or if they’re used in the abstract, I think it’s very much part of the contemporary conversation.”

In this way, contemporary Indigenous artists offer a very different way of relating to historical Native objects than the way museums typically adopt. Prombaum feels this is partly because artists learn to interact with and see things in unique ways.

“Artists are capable of understanding objects and understanding making in a way that a lot of other people from any given community aren’t,” Prombaum explained. “[Red Star, Morin, and S’eiltin] are all invested very differently in the transformative potential of Indigenous histories, languages, knowledges, cosmologies.”

For Prombaum, an artist’s ability to look creatively at objects, and use their transformative potential, helps explain the difference between “what the museum is doing for things that they are putting in the past and what these objects mean for artists who are very much working with all the potentials of these living knowledges and spiritualities today.”

‘It’s about if museums will actually give the space over to the artists to tell the stories that they actually want to tell in their ways.’ ~Levi Prombaum

Prombaum feels that, as much as museums are trying to reorient their practice, these institutions are inherently ill-suited to tell certain kinds of stories.

“I think that it’s important to acknowledge that museums, founded so frequently in these 19th-century ideas of preserving things forever in a certain state, (are) inherently conservative institutions,” he said. (They) are still, even today — even as they’re reckoning and trying the hardest that they have in a long while to reconceive of what their cultural mission actually is. They still can only tell a really small segment of stories, and they can only tell certain stories in certain ways.”

Prombaum believes that museums need to recognize their own inherent limitations as institutions by opening up space to artists and handing over authority to individuals to shape their own work, exhibits, and stories.

“It’s about if museums will actually give the space over to the artists to tell the stories that they actually want to tell in their ways,” he explained, “as opposed to force-fitting the artist into stories that museums can tell, and which are so frequently only half-satisfying or only half-capturing a reality.”

For Red Star, Mass MoCA has been an incredible example of this by giving her space and authority in her work. “This has opened me up quite a bit to have more faith in institutions,” Red Star said. She has appreciated the amount of freedom she’s been given and all the ways in which Laura Thompson, the Director of Kidspace, has worked to promote access and education through her exhibit.

“Mass MoCA is a unique institution because it says ‘yes’ a lot and it says ‘yes’ to artists a lot and it does create special things because of it,” Prombaum said.

“As an artist, to have Laura say, do whatever you want, whatever dream you have, is incredible,” Red Star reflected. “To have that kind of support is a dream come true.”

Red Star will continue to reframe Native histories and explore her Apsáalooke heritage through her art. Her new gallery exhibition, The Indian Congress, will open at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska starting January 30th.

She will contend with the 1898 ‘Indian Congress,’ when more than 500 people from 30 nations came together during Nebraska’s Trans-Mississippi Exposition. She will draw from research in libraries and archives and historic sites in Omaha and Montana — animating artifacts with sculpture, video, and fiber arts. And she will bring together photographs of hundreds of Native members of the delegatio — among them the Apsáalooke leader Meenahtseeus or White Swan. He was an artist, a veteran, and a leader of his people.