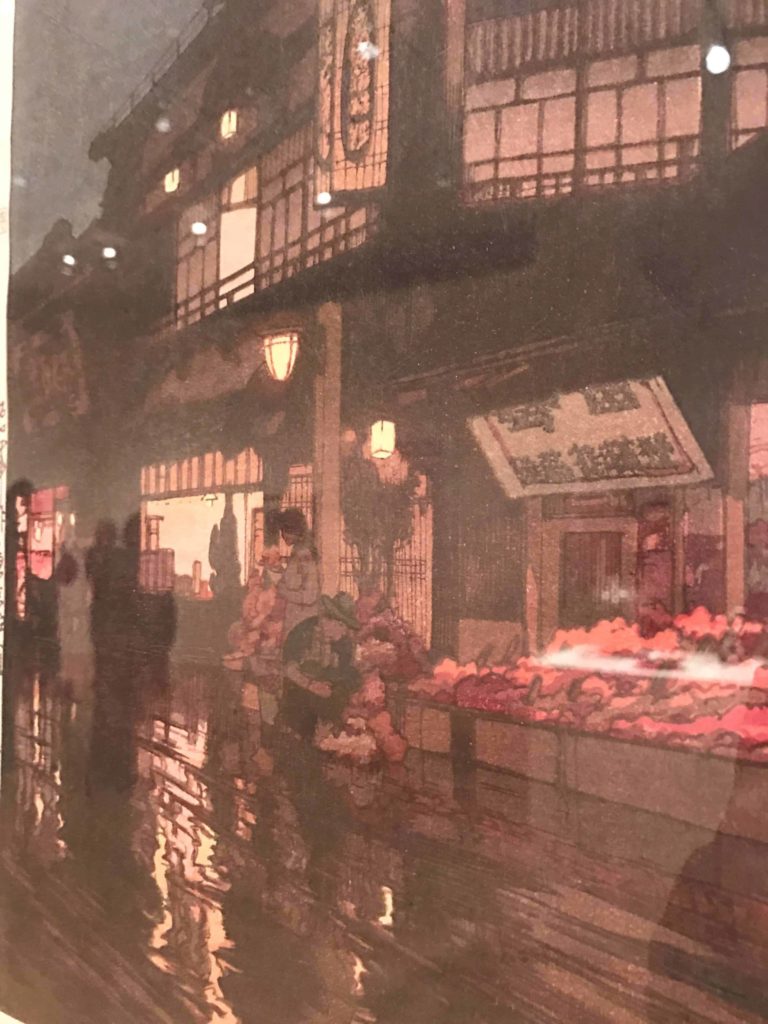

The shop or restaurant catches my eye across the way. It’s raining on a quiet street in Kyoto at night. The lights glow behind the windows and in the red globe under the eaves. On the wet pavement, two women are looking through the door, as hard to see in their red and yellow coats as college students in a crosswalk.

And it’s half an hour after sunset on a January day — in Williamstown. I am crossing a gallery at the Clark Art Institute to look closely into Yoshida Hiroshi’s night scene. In his city street, the intense golden lamp light filters into the dark in indefinably different tones, through paper lanterns and drawn blinds.

It’s a wood block print from 1933, and it looks as contemporary as a sidewalk in Cambridge with the bicycle leaning against the curb. But it’s part of an artistic tradition going back 100 years before Hiroshi painted it.

I’m walking through ‘Japanese Impressions,’ the Clark Art Institute’s winter show. And I’m walking slowly. I’ve been waiting almost a month for this. In early December I talked with Jay Clarke, Manton curator of prints, drawings and photographs, about this show, and she took me around the exhibit as it was being hung.

She shaped the show around Ukiyo-e, a tradition of wood block printmaking in the 19th century. Influential publishers would sponsor artists to paint a series of prints or post cards of Mount Fuji in all seasons or stops along the Tokaido Road. Printers could make copies of the originals and send them around the world.

A sweeping view

At the Clark, the paintings in the first room move across 150 years, from the 1830s to the 1970s. Travelers rest in Utagawa Hiroshige’s 1833 tea shop, with a pale peach and rose light in the sky and growth in the fields. The bare branches of the young tree in the dooryard are touched with white at the tips, like buds or pussy willow.

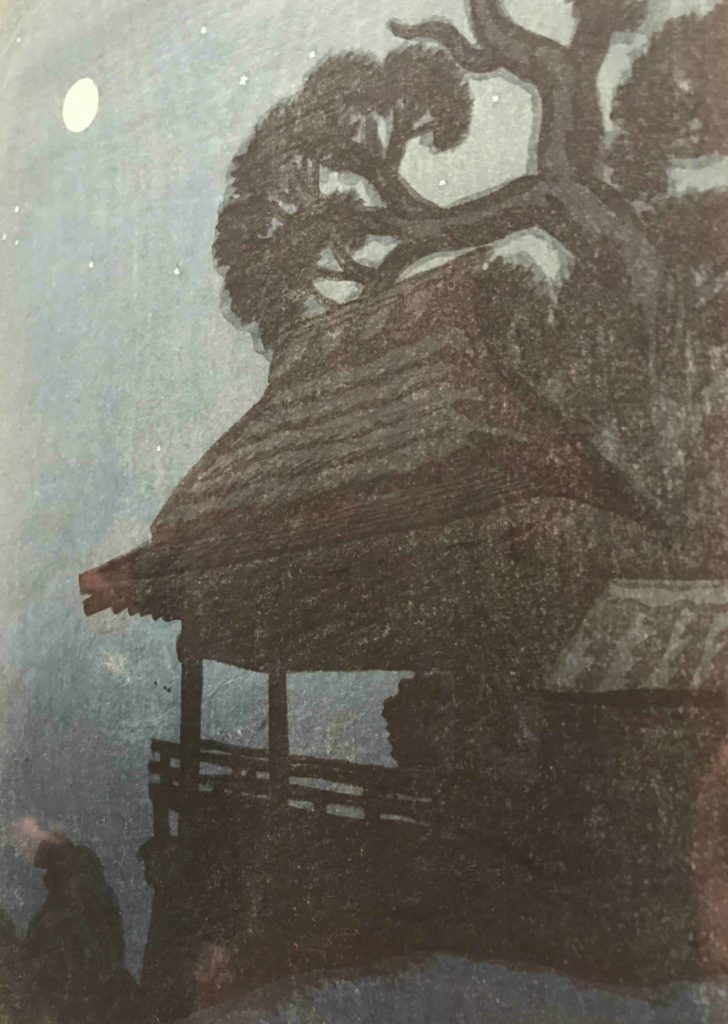

In his lifetime Hiroshige became one of the most influential and best-known artists in Japan, and by the 1890s he was well-known in Europe and the U.S. Early in the show, the Clark dedicates a room to him. He is known for detailed and immediate scenes. He painted views of Edo, his home city, like the Tekoma shrine — red maple leaves in the foreground, and in the distance a line of yellow tents leading the eye to a belt of trees.

A young woman standing near me says that the prints are made in color blocks and outlines. She seems to find the shades solid and unsubtle and the details rough. I look longer at the Tekoma shrine, the green and gold light on the fields and sunset over the sea. Its rippling hues and details in the distance are already challenging her conclusions, and I know what’s coming next.

As the galleries move into the 20th century, the work changes. Kawase Hasui’s impressionistic marsh grasses blow along an inlet, and small boats with square sails skim in the distance. Kiyoshi Saito moves to abstraction with flattened patterns and steep contrasts. In Saito’s ’s Autumn in Nanzen-ji, textured black or grey-white tree trunks line the foreground against a charcoal lawn, a low white wall and a dark red sky.

On the walls here I can see over time the shifting influences of Japanese and Western art. Japanese artists inspired painters in the West, as Japanese prints appeared in Paris, London … St. Louis and Detroit. And in turn 20th-century Japanese artists drew on elements of impressionism, abstraction, realism and perspective.

East and West

But as I look into it, this meeting between Japan, Europe and the U.S. is much larger than a conversation between Katsushika Hokusai in Edo and Vincent Van Gogh in Montmartre.

These peaceful scenes of mountains and women walking in the rain have something in common with Winslow Homer’s school houses and pastures in the Clark’s permanent collection. They were painted when places like this were disappearing and peace mattered because it was rare.

Japan and the U.S. lived through Civil War at almost the same time.

Hokusai in the 1840s and Hiroshige in the 1850s were living in the last days of the Edo period, in a structure that had kept Japan stable and protected or isolated for 200 years.

In that time, Japan’s foreign policy, sakoku, had closely limited trade and contact with other countries, especially with the West. Hiroshige saw that time fading — Bakumatsu — the closing curtain.

Why did Japan want to keep the West at a distance? Japanese leaders were studying Western science and art, but the West also carried threats — opium, cholera, colonial power … guns. In 1853, U.S. Naval commander Matthew Perry sailed four gunboats into Edo Bay and forced Japan to negotiate. Imagine a fleet sailing into New York harbor today and bombing buildings with technology we don’t have?

Japan had to open to the West. And the contact came with costs, including new diseases. Hiroshige died of cholera in 1858. He was 61. Within 10 years the economy was collapsing and the country was at war, divided between factions wanting to return to isolation and others wanting to learn enough from the West to keep their independence. In the summer of 1868, Edo fell. The capital city was renamed, Tokyo, and a new government came to power. The whole structure of the country changed.

Like the U.S., Japan was seeing a revolution in transportation, communication, architecture and gender — Women left home for factory jobs and found the same kind of independence mill women were finding in Ludlow. By the 1920s, as flappers took up the Charleston in the U.S., cross-dressing had become a popular fashion among young men and women in Tokyo.

As the exhibit moves from Hokusai and Hiroshige’s landscapes to Hiroshi’s, the world around them is changing dramatically. Ukiyo-e is holding on to places and ways of life people want to remember. But it is evolving too.

Technicolor time capsules

As the century turned, people wanted, in some ways, to look back. But they were looking with new eyes.

This is the background for the next generation of woodblock printers in the Clark’s show.

In the 1920s and 1930s a new artistic school grew with roots in Ukiyo-e — the New Print movement, Shin-hanga — artists experimenting with Western artistic ideas but returning to traditional block printing techniques.

Artists working with printers were creating increasingly complex patterns and shading. They could print lines as fine as the soft hair at the nape of a woman’s neck, textures as intricate as snow marbled on a rock face and tones as varied as firelight on wet slate, or the sky before dawn

Hiroshi began as a painter and watercolorist and traveled in Europe and America. And he became intimately involved in the printing of his own work. He worked closely with master craftsmen, but he learned carving and printing. He always worked on the most difficult sections of a print and often marked his work jizuri, self-printed. He developed new techniques for trees, water, reeds, intangible mist — greys for shadows, new plates for sharpness and new pigments to create new colors.

Kawase Hasui also had a background in oil painting, life drawing and plein air, before his print career took off in the 1920s. He painted in water color and ink wash and worked closely with his publisher and printers, testing inks and effects. Debates over color could hold up a print for years.

That kind of patience most have played a part in the wet air and flickering brightness in Rain in Uchiyamashita District, 1923. A man in a yellow slicker is coming out of a wooden gate onto wet pavement. He is a small figure, and around him stone walls are built into a hill as the foundation of a low, white-walled building as spare as a Welsh farmhouse.

In the year he painted it, Hasui lost most of his life’s work. A massive earthquake and tsunami killed more than 140,000 people in and around Tokyo, and fires devastated the city. His house and his publisher’s print shop burned.

So when Hiroshi painted his night scenes in Tokyo and Kyoto, most of those cities looked very different from these quiet streets. The low wooden buildings of old Edo were giving way to high-rises. The cities were expanding rapidly with factories and industrial construction. Hiroshi was looking back to the old city, with warm lights and wooden buildings and alleys.

Moving ahead

After World War II, chaos would evolve again into a new kind of art, Sōsaku-hanga, “original creative print.” These artists in the 1950s to 1970s entirely printed their own work, and they moved away from country scenes that felt impossibly idyllic to stark light and shadow, memorials and Buddhist architecture.

This is Japan after the U.S. dropped atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This is Japan as one of the strongest economies on the planet, on its own terms. But the conversation is still there. In these abstract shapes showing the wood grain of the printers’ blocks, I think I see elements of American Modernism and the African artists who inspired it.

But what did Saito think of the U.S. in 1970? What did Hiroshi think in 1920? He travelled through the states, and he visited Boston. I wonder how it looked to him.

As I walked home that night in the sleet, I cut through the Williams campus and crossed the quad by Sawyer Library. In the dark, lights rippled against the brick and the ice. Desk lamps shown in the tall windows, and pathway lanterns reflected in the glass. I realized I was trying to see the place with Hiroshi’s eyes.

Image at the top: Kawase Hasui, Territory of Amakusa. Courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

Sources

To fill in the artists’ lives, I’ve done some research at the Clark’s newly renovated library, outside the exhibit itself — which gives background on the artists and a timeline of Japanese history in the period. This column draws on the following.

Kendall H. Brown, Shin Hanga: New Prints in Modern Japan

Kendall H. Brown, Water and Shadow: Kawase Hasui and Japanese Landscape Prints

Yuiko Kimua-Tilford, Seven Masters: 20th-century Japanese Woodblock Prints from the Wells Collection

Edyth Polster and Henry Smith II, Utagawa Hiroshige: The Moon Reflected