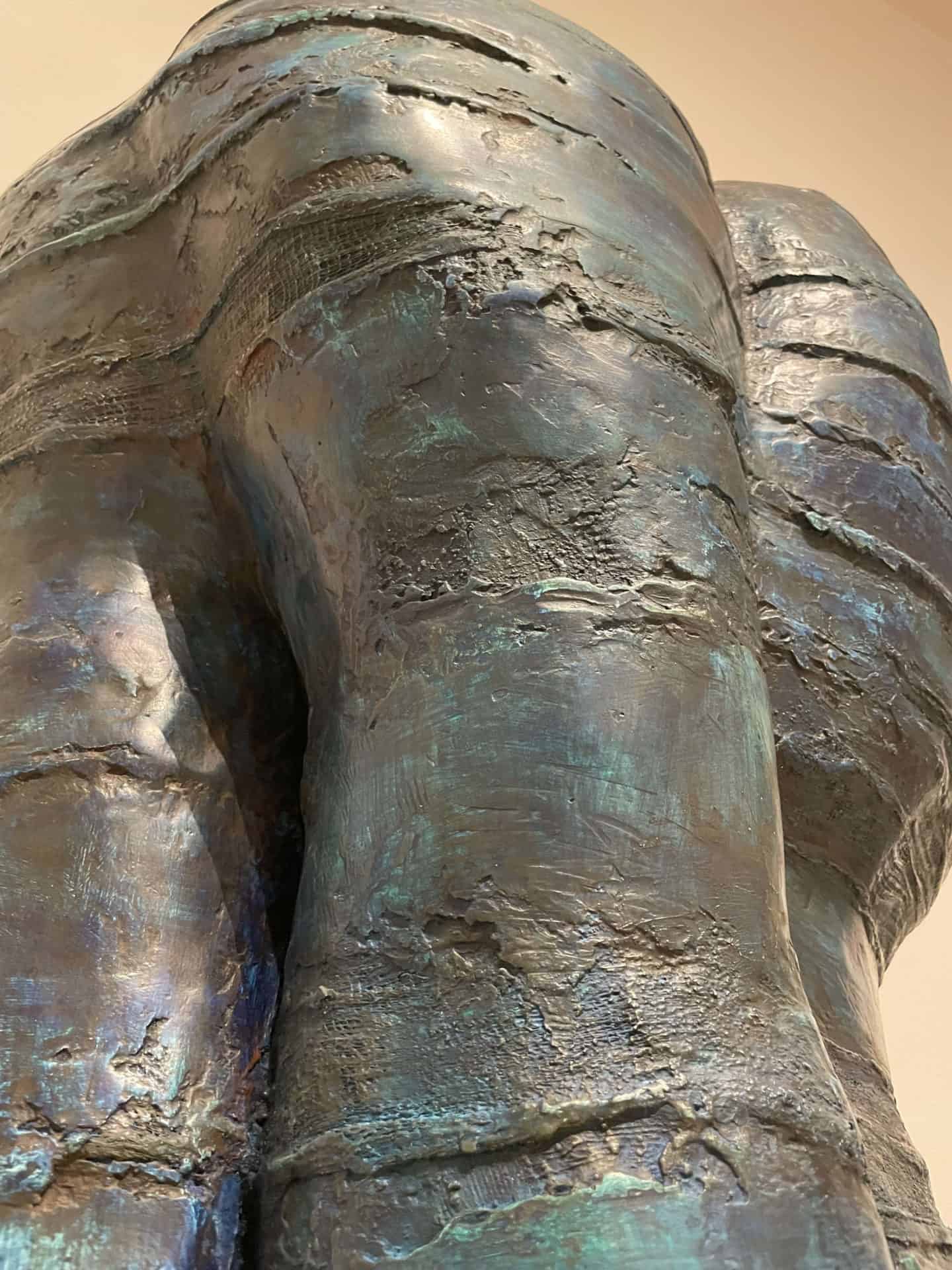

Many of the sculptures in the galleries seem to have a heavy, industrial texture, and some even have the dark-brown color reminiscent of rusty steel. At the same time, they all occupy softer forms vaguely reminiscent of the human body: a set of interlocked knees, a set of knuckled fingers, the curve of a neck.

It’s a conversation between synthetic and organic, cold and warm, modern and primeval, that seems to animate the sculptures of Mary Ann Unger (1945-1998) in To Carve a Moon from Bone. Leading an upwelling of renewed attention to her work, this is the first solo exhibition of Unger’s work in more than 20 years.

Horace D. Ballard, Associate Curator of American Art at the Harvard Art Museums and former Curator of American Art at the Williams College Museum of Art, brings this show to WCMA this summer, through December 22.

Mary Ann Unger's abstract sculpture curve in tactile blue-black helixes.

The exhibition began, Ballard says, when he met the artist’s daughter, Eve Biddle (Williams ’04), and Eve’s husband, Josh Frankel, who is a director and Williams ’02, at a cocktail party in 2018. Ballard was exploring the college’s collection then, working toward several shows.

“I was interested in WCMA’s photography collection,” he said, “and Eve’s father, Geoffrey Biddle, is a fantastic photographer. She invited me to come by to see his work. So I’m at an eight-floor walkup on the Lower East Side, and I’m looking at a 12-foot sculpture …”

He was struck by a form made in hydrocal over steel armature, taller than human height. Eve told him it was her mother’s work, made some 30 years ago, before her mother died of breast cancer when Eve was 16. He was quickly drawn into a new exploration of Unger’s work.

On the journey, he has written the catalog accompanying the retrospective exhibition — the first book-length and academic assessment of Unger’s practice. Ballard said he intended a division of labor between the exhibit and the catalog: “the catalog is deeply chronological, to give Unger the critical standing she’s never had.”

The exhibit, on the other hand, “tries to be as open as possible, playful, colorful,” he said. “It doesn’t talk about her career goals or her career – it shows her at her most rigorous and invested and gives her – gives people – the chance to make their own connections.”

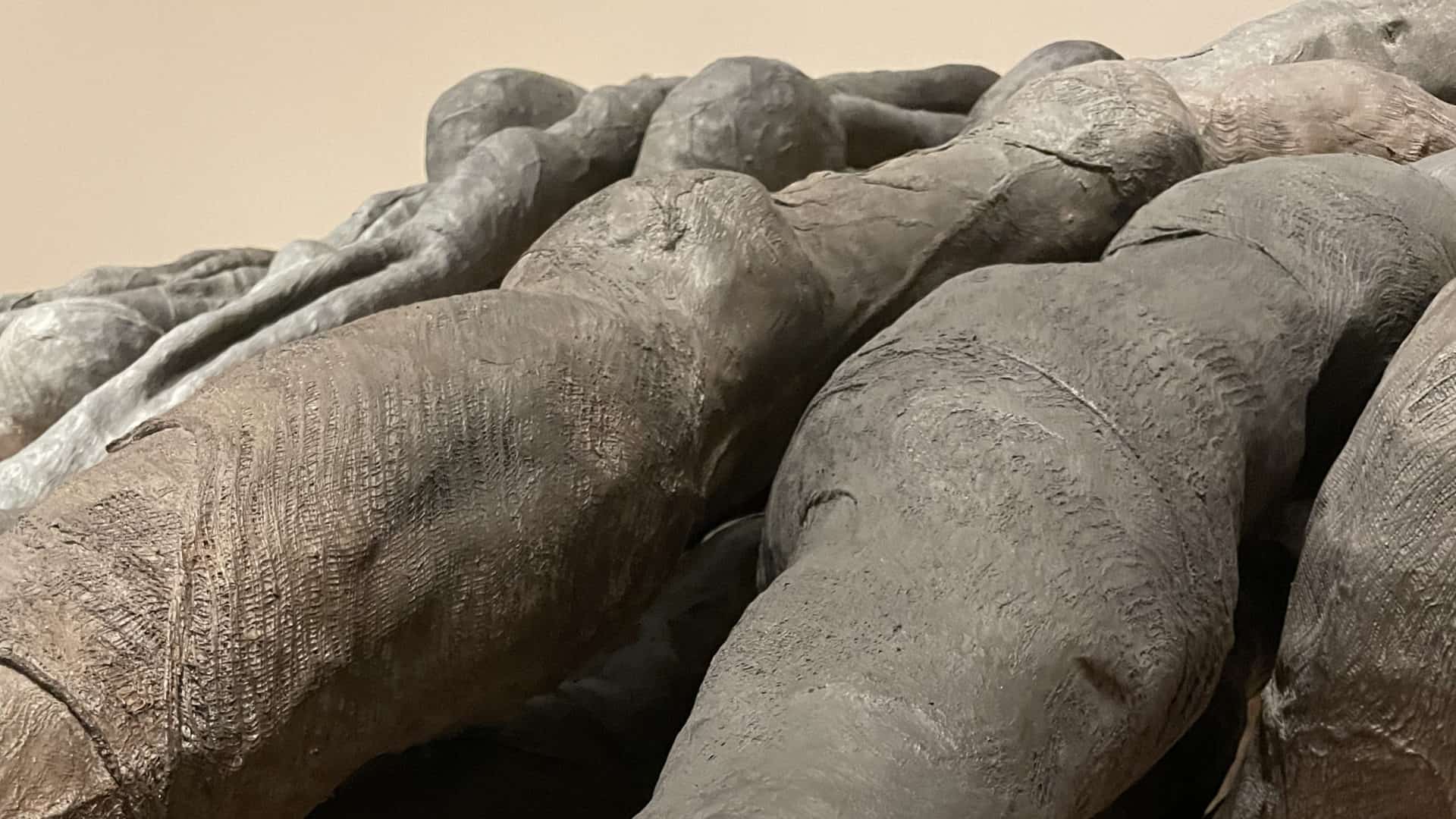

Mary Ann Unger's Bering Strait fills a gallery at WCMA in long horizontal forms.

Walking through the exhibit, his hands-off, associative curatorial approach appears. Unger’s sculptures and drawings stand out against the white walls of the gallery, emphasizing their formal qualities.

Ballard described one large sculpture series, Across the Bering Strait, as a work that stands for itself. The exhibit reflects that – this one work fills and crosses the floor of its own adjacent gallery space.

Ballard also extends this approach to the labels for the artworks, which he opens with thoughts from Unger herself and people who knew her.

“Quotes from [Unger] and from Eve start the labels, or from her friends, not my words,” he said. “A sense of rigor and play and her voice supersedes all.”

Mary Ann Unger at work in her New York studio, 1979-1980. Photo courtesy of WCMA.

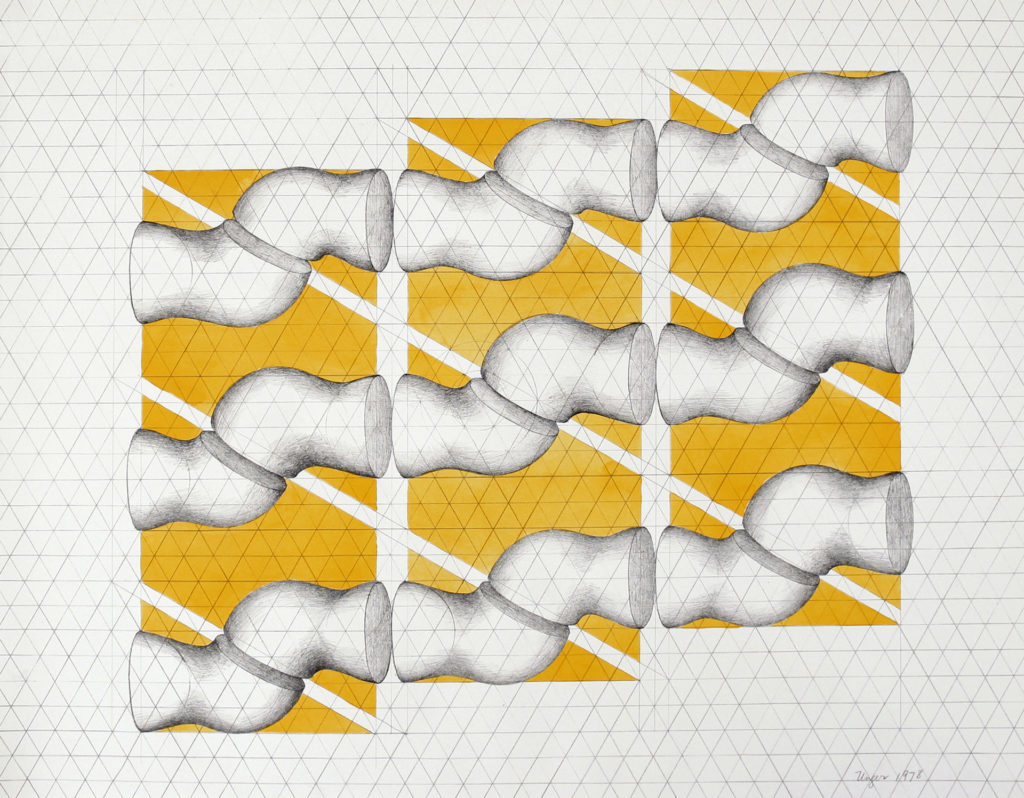

In his arrangements, the exhibit sets up an arresting interplay between drawing and sculpture, between 2D and 3D, and between Unger’s rounded, organic forms and her use of rigid, linear organizational schemes, or grids. Ballard described how these polarities lend a deeply architectural quality to her work and to her process – the way that she annotates her drawings, for example.

“She comes from a long line of MIT engineers,” he said. “… She draws organic forms from negative spaces in the grid – mathematical, meditative… that idea of an emergent line – that’s the part that blows my mind. Her sculptures are built on a grid.”

Critics have extensively analyzed the grid as a visual form which is distinctive to modern art. Ballard referred to Rosalind Krauss, who first theorized the grid’s spatial qualities in her seminal 1979 essay “Grids.” In its flatness and its order, she argued, the grid is “what art looks like when it turns its back on nature.”

Krauss also argued that the grid is a structure which possesses a unique ubiquity throughout modernist art of the 20th century – it is a prominent form in her examples, which include the works of Piet Mondrian, Agnes Martin’s Untitled (1965), and Jasper Johns’s Gray Numbers (1958) – and appears “nowhere, nowhere at all, in the art of the last one.” As such, the grid “functions to declare the modernity of modern art.”

Mary Ann Unger's sculpture, Benchmarks, is at To Shape a Moon from Bone at WCMA. Photo courtesy of WCMA

Ballard spoke of how Unger’s use of the grid — an exchange with the work of earlier artists – nuances existing histories of sculpture, and deepens her art historical legacy.

“She worked in hydrocal and welded steel,” he said, “much less figurative or repetitive than her drawings. She still has her base on a modernist grid. It’s not how we talk about postmodernist art, or women working in sculpture. She’s part of a generation of women who have never gotten their due.”

Unger is identified with sculptural postminimalism, he said, which arose decades after the modernist works Krauss analyzed as the initial archetypes for the grid. But her use of the grid takes the earlier style in entirely new directions. For Ballard, her use of the grid represents a substantive exchange with her modernist forebears, contesting the grid’s possibilities, as well as its limits.

Mary Ann Unger's abstract sculpture shows interwoven curves at WCMA.

Like some of her peers and predecessors, she would trace geometric patterns across space. But she would bring together overlapping patterns and shapes and focus in on the spaces between them. And those shadow spaces became the curved, organic forms of her sculptures.

“She was reading Krauss,” he said, “thinking about the capacities of the grid and what her training gives her and does not give her. The grid not just as mathematical.”

For her, it becomes a way to discover “older forms, spiritual, ritualized, endemic to civilization across time and space. Holding the limits of the grid, she’s thinking, ‘if I want to get to organic forms – stone, bone, how skin forms – how can I get there?’”

She definitely gets there. A sense of the organic dominates the external form of a sculpture like Shanks – newly acquired by WCMA – which resembles three standing, knuckled bones. The grid is within – the work’s wall text describes how the steel armature inside is built “from gridding two inches square…an organically shaped, dimensional grid,” which Unger then wrapped in cheesecloth soaked in hydrocal, her plaster of choice.

Sculpture takes on the tensile strength of bone in Mary Ann Unger's work at WCMA.

Unger’s marrying of organic forms with the modernist grid is most visually obvious, to my eye, in Unger’s paper drawings. In Untitled (Study for Hexagonal Quintet) (1978), rounded, joint-like forms repeat against a triangular grid.

It’s not a drawing of immiscibility, of organic growth against mathematical order — the joints have been sliced open along regularized axes that comprise their own grid, openly revealing the flat planes hidden within organic forms.

Ballard suggested that Unger would not necessarily have seen drawing and sculpture as entirely separate practices.

“Artists don’t always think about the differences between a 2-D study and a 3-D form,” he said. “It’s all art — nothing is lesser. As gallerists and curators, we do see a difference.”

In either medium, what first drew Ballard to the artist and her work shows clearly.

“I am drawn by its rigor,” he said, “by how completely focused it is on three formal qualities, shape and volume and line, and I am deeply interested in how over the curve of the last 25 years, color comes in, doing things I had not seen color do before. Not that color becomes line, or line thinks about color and shape, like color field work — but color becomes expressive, an emotive fourth dimension.”