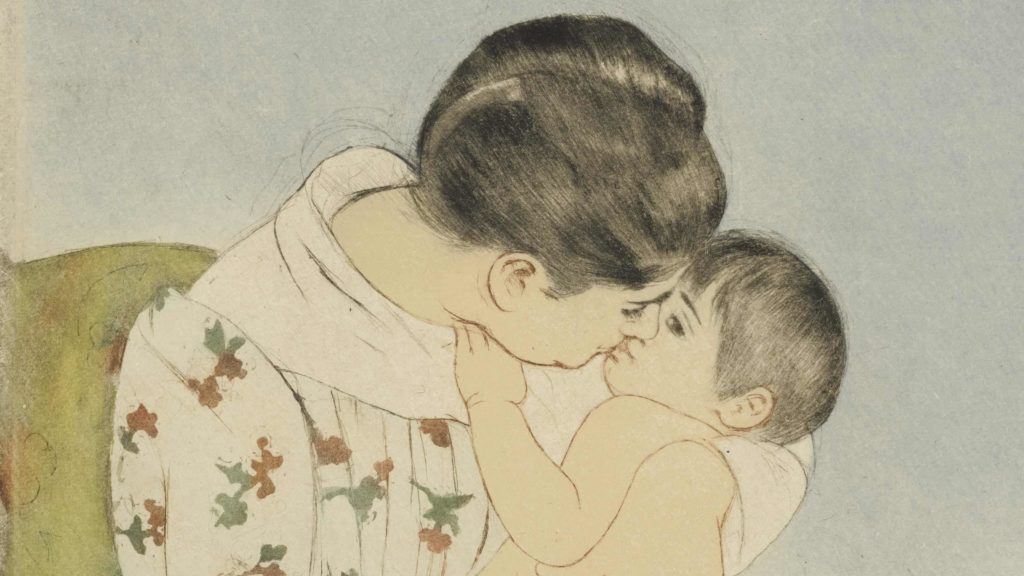

A woman is sitting in in a moss-green cloth chair, holding her son. He looks about two years old, and he is lying relaxed against her, holding the collar of her dress with one hand. She is wearing a light summer print in red flowers and green leaves, the sleeves loose and the neck a fold of white cotton, her hair in a French roll, and she is leaning down to him.

It’s called A Mother’s Kiss. Mary Cassatt brings an Intaglio color print into Hue and Cry, the Clark Art Institute’s newest winter show.

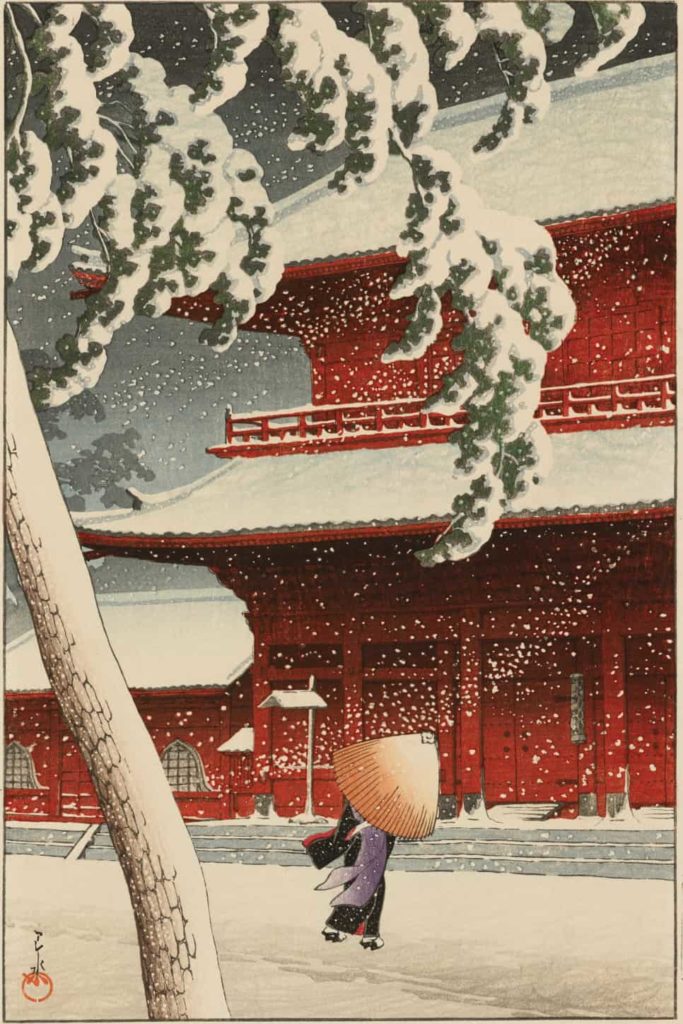

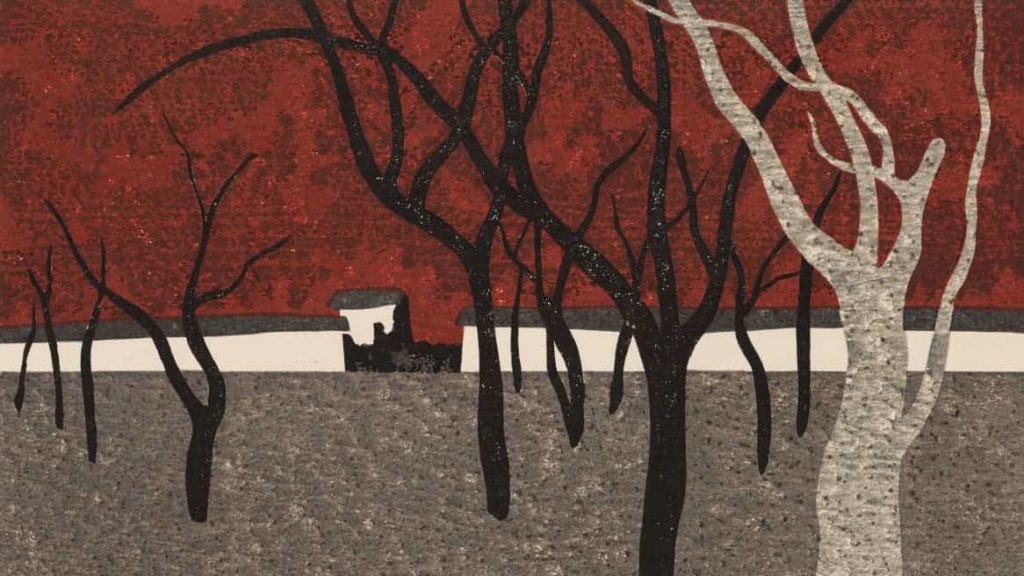

Anne Leonard, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, that color prints were contraversial in Paris in the 1890s — while artists experimented and fought for the form, critics scorned it and the Salon forbade it. At the same time, Japanese woodblock prints had been influencing the Impressionists for decades.

A close-up shows Mary Cassatt's Intaglio print 'A Mother's Kiss' appears in Hue and Cry at the Clark Art Institute.

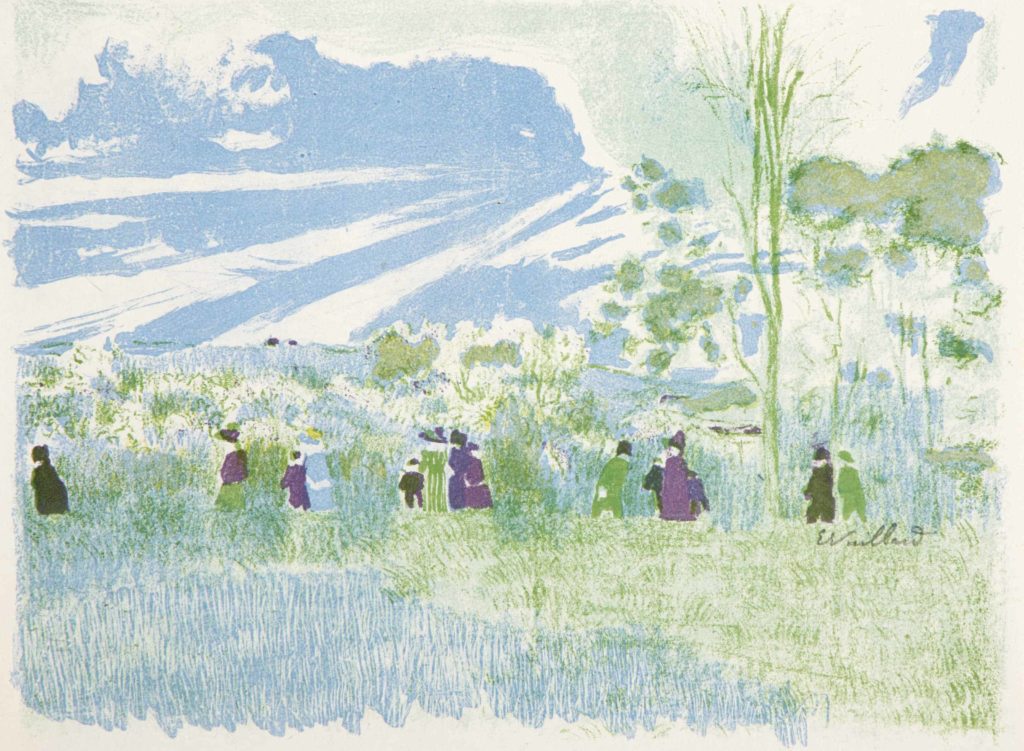

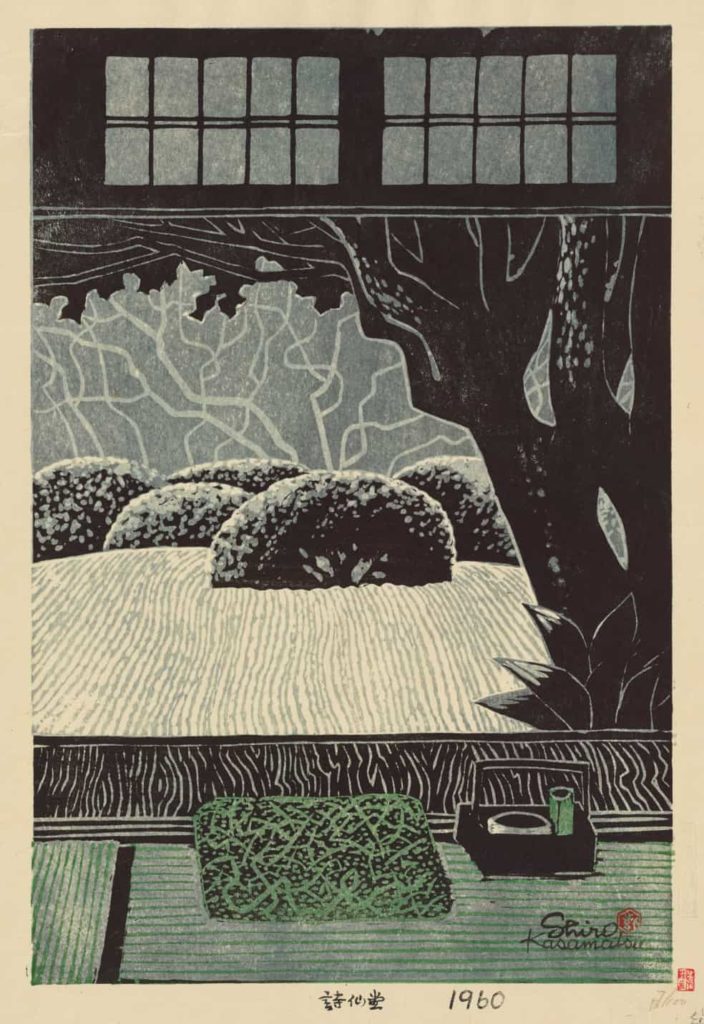

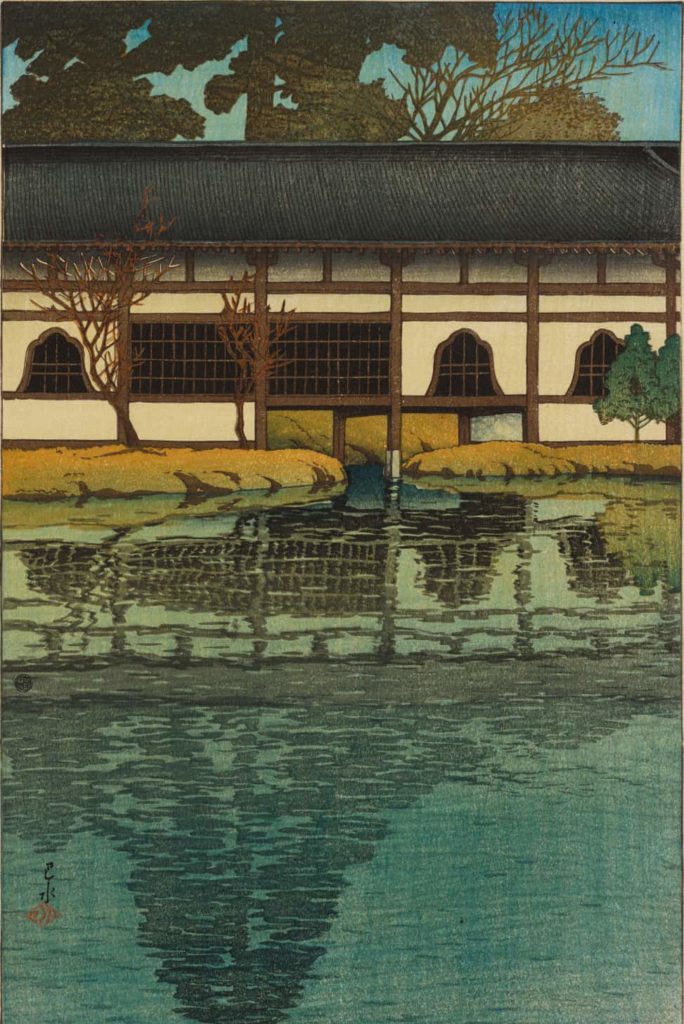

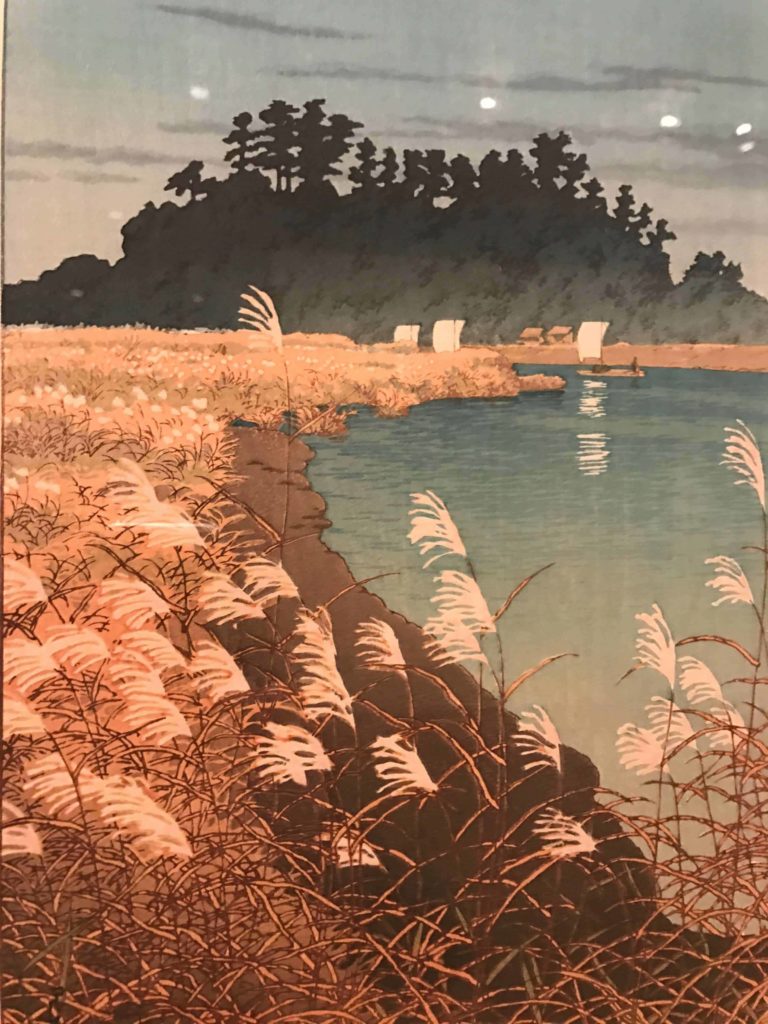

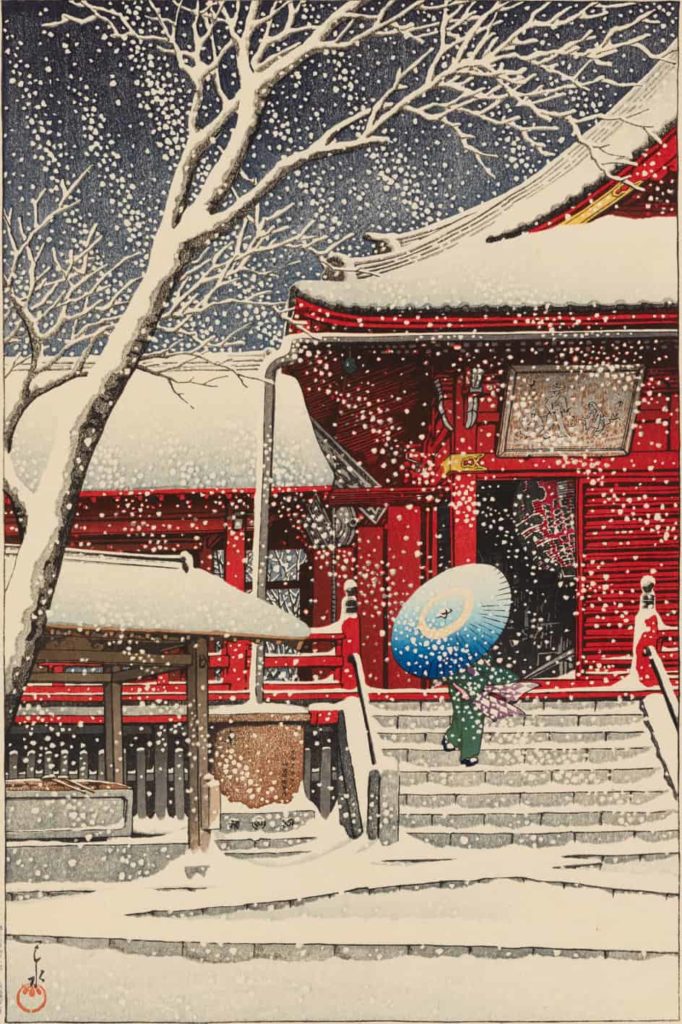

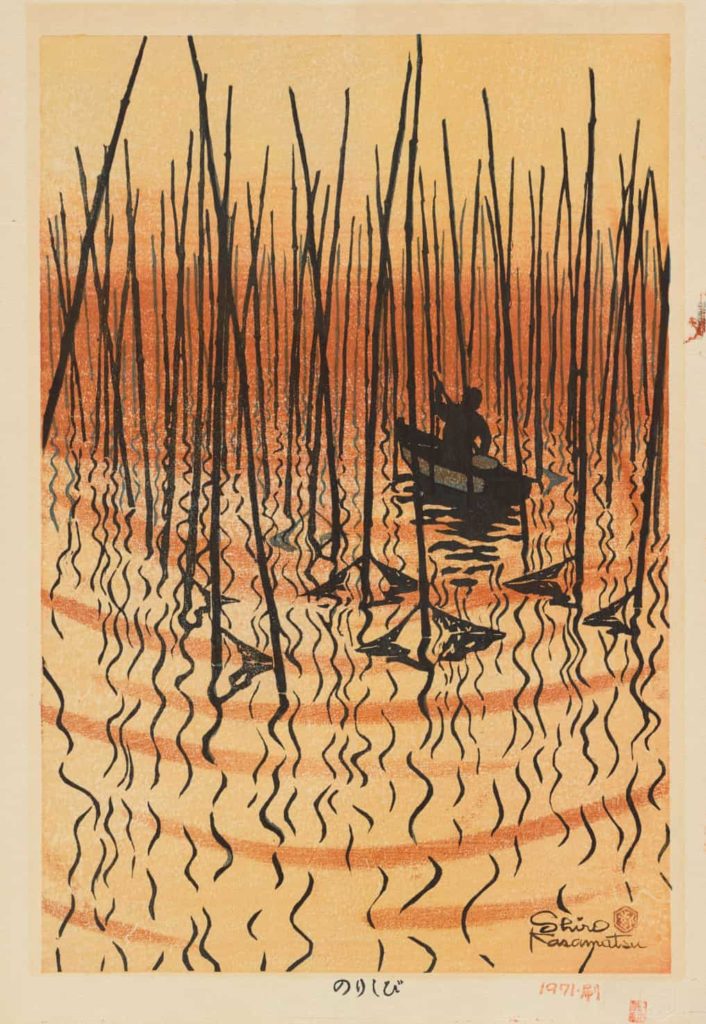

Across the Clark campus, a companion show, Competing Currents, shows their vivid, finely shaded colors. Looking at the full moon over Shima beach, I had to wonder how Mary Cassatt came to know these Ukiyo-e scenes, and what she thought when she saw them, how they influenced her work, and how she played with those influences and her own ideas …

And one thing I appreciate about the Clark is that when I walk out of a show with a headful of questions, I can wander into their library. Leafing through a catalog for Mary Cassatt: The Color Prints, I learn the print I’ve just been looking at has a clear point of inspiration. On April 15, 1890, the École des Beaux Arts in Paris held a show of 725 Ukiyo-e wood-block prints and 326 books, all leant from French collectors.

Cassatt saw them more than once. She wrote to Berthe Morisot the day she first came — “You who want to make color prints couldn’t dream of anything more beautiful. I dream of it and don’t think of anything else but color on copper.” And then they went back together.

A fill moon rises over the water in Tsuchiya Koitsu's print, Suma Beach. Press image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

It was not the first time Cassatt had felt the power of Ukiyo-e or the first time she had explored printing in her own work. She would have known Japanese woodblock prints for some 20 years — she had many of them on the walls of her studio. And she had been making etchings and aquatints since the 1870s.

But this gathering in 1890 inspired her and Morisot with new energy. They spent the summer near each other in the country, and Cassatt returned to Paris to work with the color press in her studio. And she exhibited a set of 10 prints a year later.

She wrote that she had made them under the influence of these Japanese artists … though did she mean the effects they could achieve in carefully inking their blocks, their clear tints, their moments of abstraction, or their subjects?

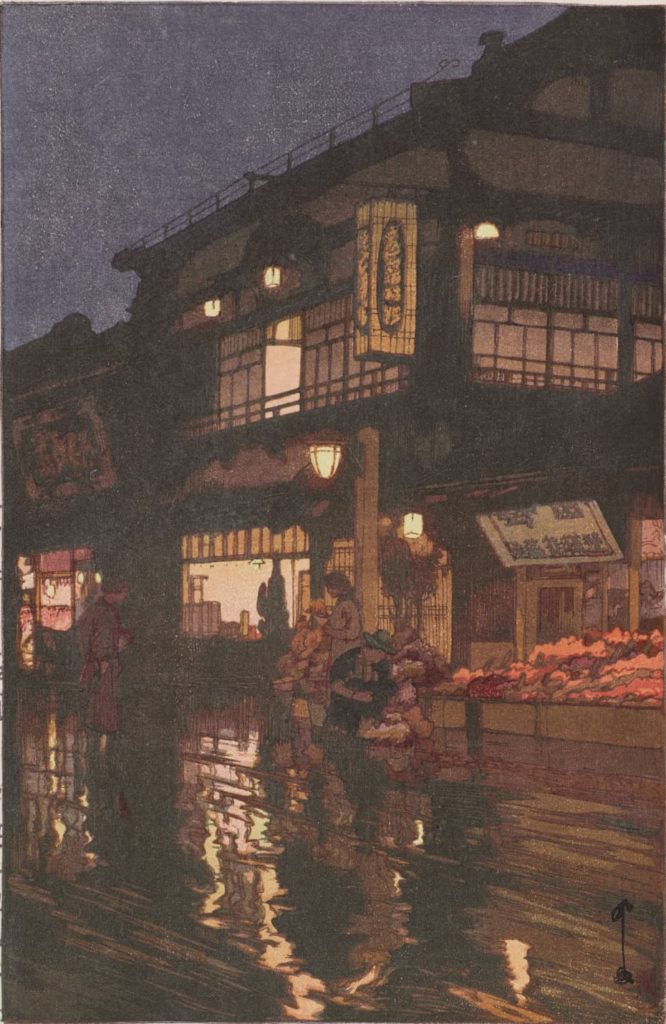

Ukiyo-e prints often show moments in daily life, as guest curator Oliver Ruhl told me in the fall — a picnic by a waterfall, a restaurant in a lighted street, full moon on the tideline, women walking in the rain … geishas applying makeup and actors backstage. And they often have a rich appeal to the senses. They were made for pleasure. And in Tokyo, as in Paris, they were almost all made by men.

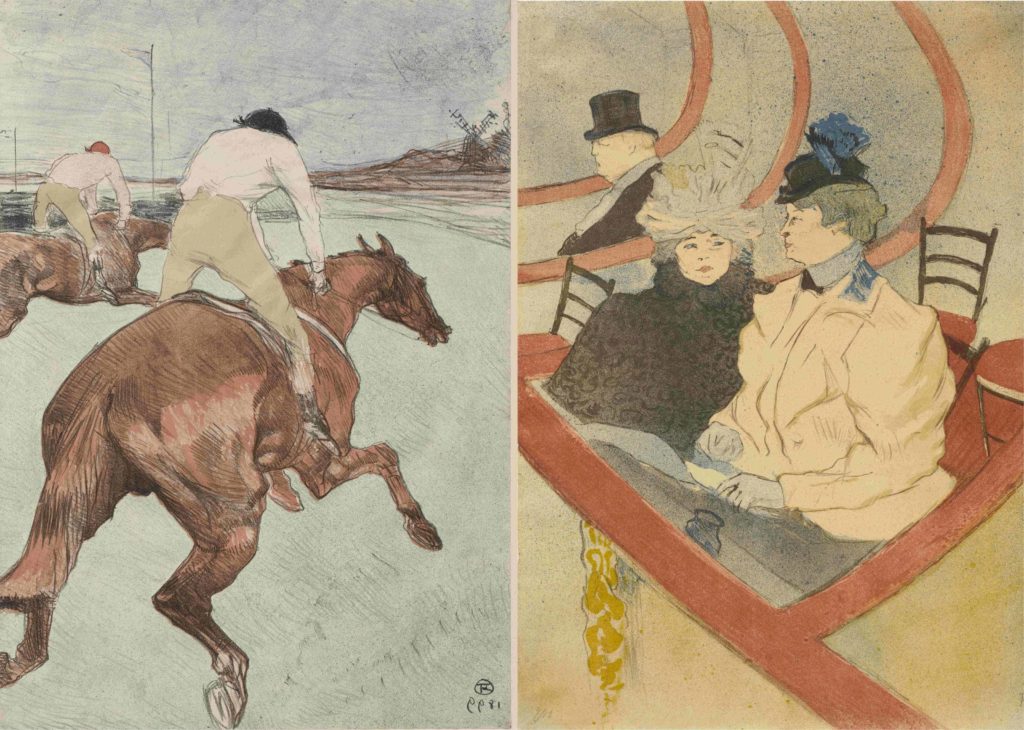

A woman artist who wanted to show her work could not paint the kinds of vigorous encounters men would, Nancy Hale says in her biography of Cassatt — a woman could rarely even paint scenes outside her own house and garden: “what mattered was not so much what a woman did as what she could be ‘seen to see.’” Cassatt could go out dancing with friends, but she could not publicly show an image of two women waltzing together at the Moulin Rouge, as Henri de Toulouse-Laurtrec does in this show.

Henri Toulouse-Laurtrec's The Jockey and In the Grand Tier appear in Hue and Cry at the Clark Art Institute.

And so I am intrigued to find that in this same sequence of prints, Cassatt has shown a woman standing over a washbasin, wearing a bathrobe or towel casually stripped to the waist. Here is a woman moistening an envelope to seal a letter, and here is and another sitting on her bed, half dressed, putting up her hair.

Did printmaking give her room for a different kind of intimacy in her work? As she describes it, her printmaking was an intense and hands-on practice. She inked each plate individually, and she would redo the colors, create ‘errors,’ overlapping tones or scraping off pigment, wiping the ink for effect.

Hale describes her absorbtion — Cassatt spent many days working in her studio from 8 a.m. until daylight failed and then spent her evenings on printing. “The printing is a great work,” she wrote in a letter. “Sometimes we worked all day (eight hours), both a hard as we could work, and only printed eight or ten prints in the day.”

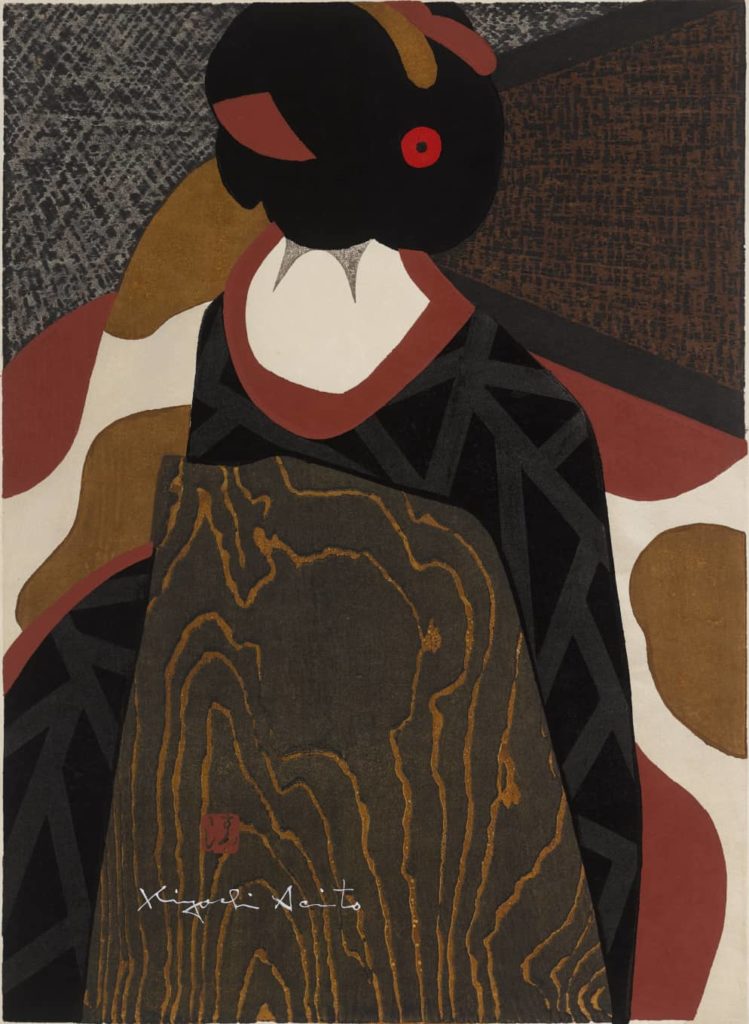

Hashimoto Okiie, Young Girl with Iris, 1952. Image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

The Prints catalog and the Clark suggest she earned recognition for them too, though it may have come slowly for her, at the time. Colleagues and collectors ignored her, and Degas, her mentor, damned her with faint praise.

But Camille Pissaro, who showed alongside her in 1891, called her prints rare and exquisite works and wrote to his son with astonished enthusiasm.

“It is absolutey necessary, while what I saw yesterday at Miss Cassatt’s is still fresh in mind, to tell you about the colored engravings she is to show … the tone even, subtle, delicate, without stains on seams … blues, fresh rose …”

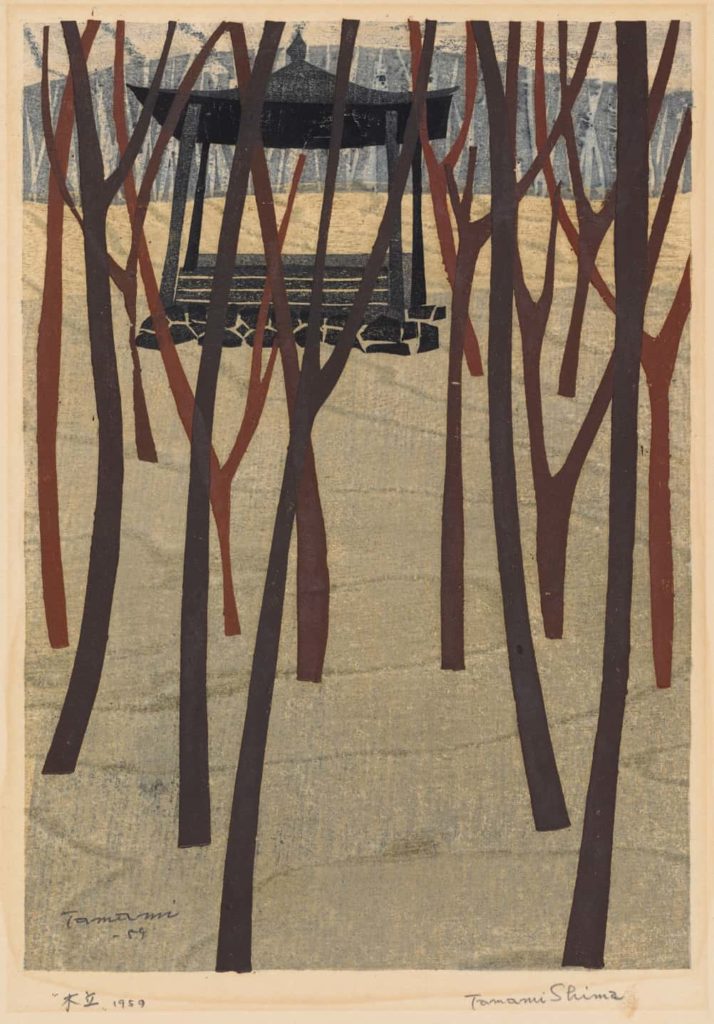

I’m glad to have seen them and the kinds of images that she saw as she imagined them. This meeting of Japanese artists and Parisian artists may have been partial — as much as I’d love to imagine it, Mary Cassatt likely never spoke with an artist like Shima Tamani, the one woman in Competing Currents, as Cassatt is the one woman in Hue and Cry. It would have taken time travel for the two of them to meet over a cup of coffee — but surely they could have had a lot to say to each other.

And in some ways this feels like a good place to bring them together. As I walk out to look across the snow-covered reflecting pool, I remember that the whole of the museum I’m standing in has been re-imagined and remade by a Japanese architect. In a collection of Impressionists, I’m standing in Tadao Ando’s vision of a mountain ridge in the snow.

Clouds and sun pattern the sky over Stone Hill at the Clark Art Institute.