The Williams College Museum of Art has recovered a vanished room.

It feels like a kind of mythical medieval place, with a floor of handmade tiles and dark plaster walls, oak beams and diamond-paned windows with inset stained glass. It was designed almost 80 years ago, walled away and almost forgotten.

The young museum built the Edwin Howland Blashfield Gallery in 1938 to resemble a gallery at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, said Kevin Murphy, senior curator of American art. It was not a replica of a chapel or a real courtyard in a palace in Granada; it called to a medieval style and time.

In the next decades the gallery often showed works from the museum’s growing holdings from 12th- to 16th-century Spain and France. About 10 years ago, the museum was becoming a white-cubed kind of space, and the director at the time wanted more room for newer work. So the gallery was covered the walls in dry-wall and plywood, even the windows, and turned into a gallery for works on paper.

But Murphy said the new space never felt wholly right. The floor and the ceiling remained, and so it never fully became a blank, neutral room.

In the last year or so, he and former director Tina Olsen had been talking about spaces with their own character, as the reading room next door has kept with its shelves and woodwork. And Murphy suggested bringing the medieval room back to light.

This fall it has re-opened with his exhibit “The Presence of Absence,” a gathering of mostly Medieval objects, hoping to broaden their reach and the questions they raise.

“No other museum would let the Americanist go nuts with Byzantine through early Renaissance objects,” Murphy said. “If I worked at the Met and asked to do a project at the Cloisters, they’d probably put me in Bedlam.”

He thought of the Middle Ages in the Western tradition but slipping farther and farther into unfamiliar ground, and he wanted to draw people to these objects in new ways

a favorite place he has recently visited, the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles, whose founders, David Hildebrand Wilson and Diana Drake Wilson have a background in film, and create exhibits he finds beautiful, strange, disorienting and elegant, like a rooftop Moroccan courtyard with live doves.

In the middle of his medieval exhibit, Murphy has set a pigeon lamp — an oil lamp in the shape of a bird.

“We have no idea where it comes from,” he said.

The metalwork is supposed to be Belgian, but historians have placed the work anywhere from Persia to a Flemish colony in South America.

Murphy himself has tried to identify the kind of pigeon, with its top-knot and banding, short body and upright tail, and has found the closest resemblance in a breed from India.

He welcomes the mystery around the lamp, deliberately challenging the idea of a museum as a place where every object fits cleanly into a timeline.

WCMA has some 15,000 objects, he said, from the hands of Egyptian mummies to contemporary paintings straight out of the studio. It has never been a museum of exhibitions neatly arranged in chronological order, but of installations around ideas.

In his exhibit, he wanted to create a place where the objects belong, and finding a way through them takes thought, like a quarterback looking for gaps in the defensive line.

Icons hang from the ceiling. Limestone capitals rest on the floor. And the windows light the whole room.

“I’ve never been able to curate in a space that only uses natural light,” Murphy said.

In the afternoon, bright, sunshine rakes one capital. In the morning, the glow falls on the gilded paintings on the inside wall.

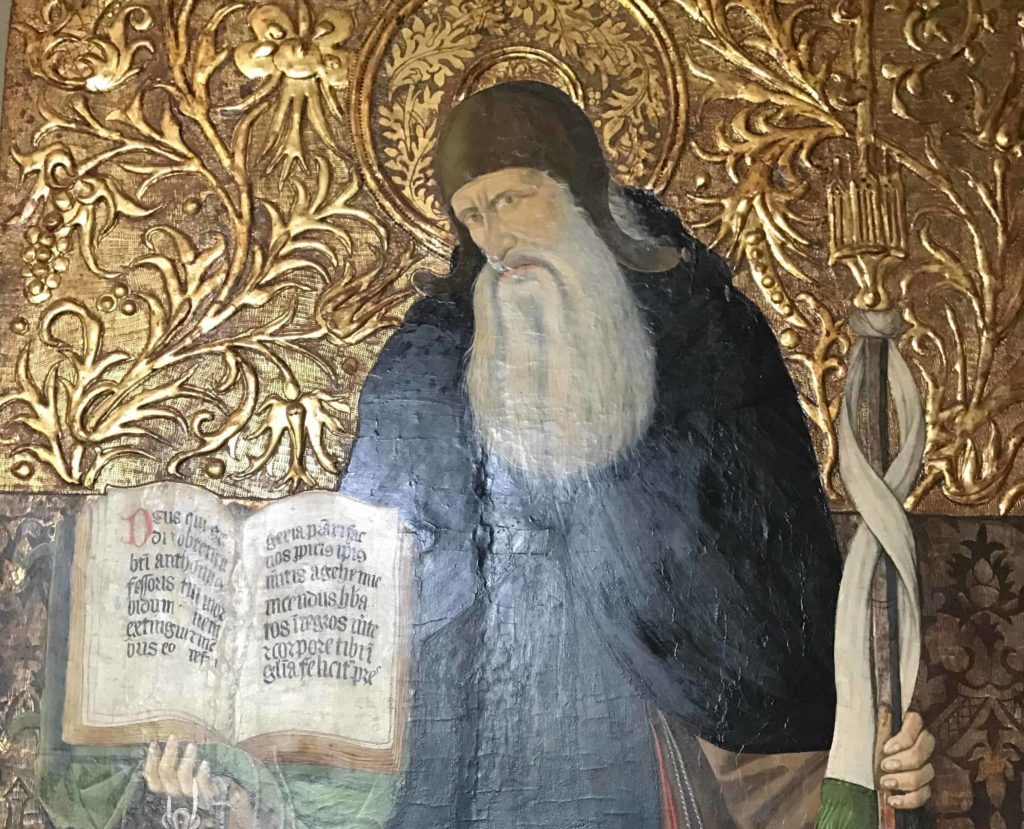

St. Lucy, always a saint of light and sight, stands in a golden haze with a tranced gaze, carrying a plate with its own half-lidded eyes. Murphy explains that for more than a hundred years, she was hidden too — a later artist overpainted her, and art conservators found and rescued her in the 1950s.

The exhibit explains her background, but often it focuses on objects in other ways.

“The information on the labels may not be what you expect,” Murphy said. “It’s not about the iconography, the subject matter, who the people are.”

Looking at a stone capital showing a damned soul, the show considers malicious spirits and how people today, whatever they believe, may bring the idea of a demon into an ordinary conversation.

A carved ivory triptych here once helped to determine workshop practices in the middle ages, because different craftsmen carved the central panel and the two wings. Murphy is showing it closed and asking instead how a workshop in 15th- or 16th-century France would have had ivory to carve.

Elephant herds are smaller today by many orders of magnitude than they were when this triptych was made, he said, and still elephants are killed for their tusks.

“Ivory and gold are still prized,” he said, “even though gold mining is incredibly hazardous to the environment. I’m from California, and whole areas there were mined with high pressure hoses, and river environments were just washed away.”

These objects touch on contemporary forces — climate, extinctions, hurricanes — and they may challenge the way people think of the time when they were made.

Europe had long and varied contact with the Middle East and Africa, he said. A real courtyard in a palace in Granada would have had walls of intricate geometric patterns and Arabic script, as the border between Europe and the Islamic empire stretched from Byzantium to Gibraltar.

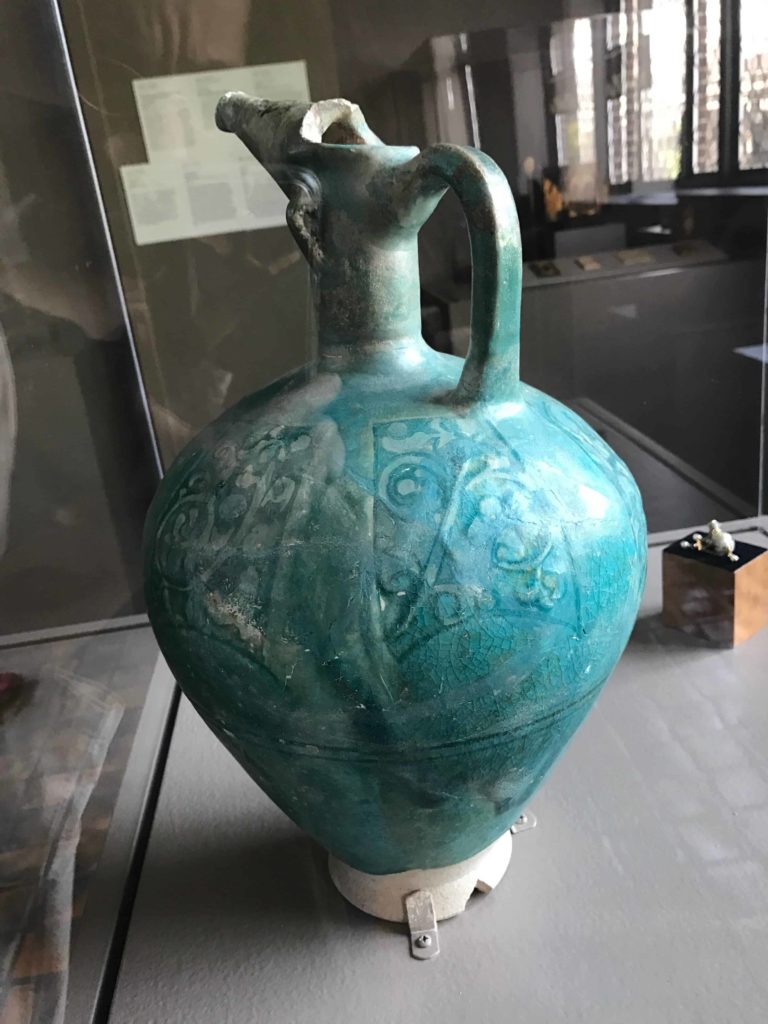

The triptych, carved on Ivory from Africa or India, sits near a Persian pitcher and a Byzantine coin stamped with an image of the emperor.

This story first ran in the Berkshire Eagle — my thanks to Features editor Lindsey Hollenbaugh.