Two men face off on a round wooden platform, Their feet are playing percussion with the friction of the stage against the floor. Their movement has roots almost 3,000 miles away, in cockfighting rings in Mexico. But they are not posturing with the bravado and violence of a blood sport — they are dancing together.

Acclaimed artist Armando Guadaloupe Cortés invokes and challenges traditions from his native land in his art installation, Castillos, at Mass MoCA. And he returns this month in a series of performances to animate his artwork.

Their footwork becomes a test of endurance and coordination, and balance. — Armando Cortés

On February 3 and 4, he and fellow artist M. Elijah Sueuga will shape a call and response with film and sound. They call the work La Seca, the dry season in a stretch of land through Mexico and into the Southwestern U.S. — Sueuga’s ancestral homeland lies at the north end and Armando’s at the south.

And on February 18 and 19, Cortes and his brother Juvenal will perform a new version of aún los gallos lloran (Even Roosters Cry), the work they brought together for the opening of Castillos a year ago.

Their footwork becomes a test of endurance and coordination, and balance, Cortés said on zoom from his home and studio in Wilmington, in Southern California.

He has lived here for many years, but he was born in Urequío, a small farming community in Michoacán, Mexico, in volcanic highlands near the Pacific, as warm as Southern Florida.

He roots this installation and much of his artwork here, in the land where his family has lived for generations. He has built pillars and shelves of cedar wood and adobe and set elements in the niches, natural, spiritual, performative or healing.

A Datura seed pods sits on a pillar of adobe clay in Armando Guadalupe Cortés’ 'Castillo' at Mass MoCA.

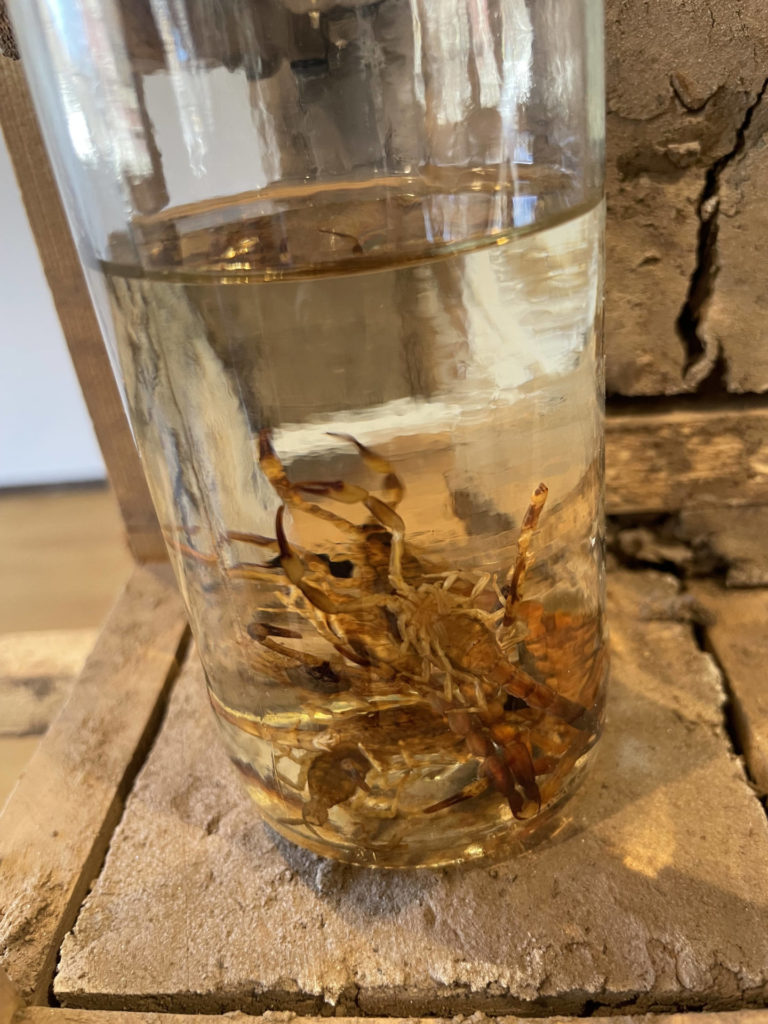

Some of them will appear in these performances. He has made a mask from an armadillo shell, the kind his father or uncles might have made and worn to holiday parties when his parents were young. And from a cedar knob hangs a pair of red leather boots with metal spurs.

They are a work on their own, he said, and he has inset them into this larger installation, because they are related to his performance in a way — their design draws on the way cockfighters will outfit some roosters with blades when they fight.

He has played with the idea of the cock fight in earlier work, he said, but never in motion. Before this show opened, he had made an installation in the opposite shape — instead of the round stage, he created the seating for the arena, a structure moving away from the spectacle.

Here he felt very comfortable with Mass MoCA curator Susan Cross, he said, and with the space in the old mill where he was building this new work, and so he felt ready to perform.

Artist Armando Guadalupe Cortés, whose work is on view in 'Ceramics in the Expanded Field, gives a collaborative performance with artist M. Elijah Sueuga, converging on their interest in sound and shared geography. Press photo courtesy of Mass MoCA

The cock fighting ring is prevalent in Mexican culture, he said, especially in the countryside. People keep roosters for sport; it’s something he grew up with and still sees. But his real interest lies in in the posturing, and in the rules and beliefs that grow around the contest.

“One that always strikes me is that the physical strength of a rooster comes from his father, but the courage of a rooster comes from his mother,” he said. “So if a rooster, no pun intended … or yes, pun intended … ‘chickens out,’ the mother is blamed, and both the mother and her offspring will be killed.

“But if a rooster is not strong enough but puts up a good fight then the mother will be praised over the father. So it has these really gendered rules, and of course they’re coming from a male perspective.”

People put these macho ideas onto an animal, a bird, and the contest between the birds grows complex relationships with contests between men. Cortés explores them … and turns them inside out.

‘The physical strength of a rooster comes from his father, but the courage of a rooster comes from his mother.’

“Equating animal and human is another interest of mine,” he said, “and here I equate them and put the space together.

“But rather than just perform them, rather than creating a spectacle of macho bravado and maleness, the idea is that it’s this dance where we have to be in balance — where both persons are trying to perform a dance, but we have to keep up with each other’s pace, because as the weight shifts and as we’re stomping, that movement with our feet is physically throwing us off.”

The performance has an element of competition, he said, but but more a balancing act. The dancers have to work together. To perform their own movements, each one has to stay on the platform, so they have to respond to each other and move in tandem.

The deep red leather shoes with blades on the sides evoke violence more directly. For people walking through his show in the past year, he hopes they will act as a tease, an expectation.

“By not using them yet, it’s a play on not allowing them to be purely spectacle,” he said.“It’s my statement on performing when I am ready, when I want, as I want. And I’m going to use my dancing boots.”

‘It’s my statement on performing when I am ready, when I want, as I want.’

He will wear an element from his installation though — and this one comes from celebration. He has made the kind of mask his family would have worn for Los Posadas, the celebrations leading up to Christmas.

He also has masks here made by unknown artisans and craftspeople, similar to masks throughout Mexico, but these are from his family’s home region. They are traditionally used for dance and storytelling, he said.

The one he made comes out of a family story. Years ago, he was refinishing a wooden bench, and one of his uncles, a generation or two older, was watching. (“He’s my mother’s cousin,” Cortés said, “but in Mexico, your parents’ cousins are uncles, because cousins are the same as siblings.)

His uncle said, “You like to make stuff? … We used to make masks — your dad, your uncles, all of our grandparents — we all made masks.”

He talked about the kinds of trees, types of wood, types of fibers — and about one of his own cousins, who would wait until the last day before a festival to make his mask, sometimes until the morning of the festival.

“He was a good hunter and trapper,” Cortés recalled the story, “and he would go out into the hills, into the chaparral, and he would come back in an hour scraping an armadillo clean. He would wear the shell. It was intense.”

Cortés was working then as an exhibitions production manager at the Fowler Museum of Cultural History UCLA, where he earned his undergraduate degree. He knew the head conservator, and they talked about his family’s tradition and the armadillo shell masks.

Cortés learned that the museum has a huge collection of armadillo masks from that region. His family has taken part in a centuries-long tradition.

Artist Armando Cortés returns to his installation Castillos, in Ceramics in the Expanded Field, with a performance activating his artwork. Press photo courtesy of Mass MoCA

A generation ago, the practice was still living and present in their town, he said. Earlier elements wove through Catholic festivals — masks and dancing and weird creatures, like caricatures, demons and cows, might appear with saints and effigies of the Virgin.

And then, in the ’80s, the town became divided. A more formal church took hold, and the community celebrations have faded.

So he decided he needed to carry on the artform, while he still knows people who know how it felt. Then he will have the knowledge in wait, he said, for whenever he is ready to use it.

And he will know from their stories the holiday reunion energy of those days, when they would carve a mask for fun, for beauty, to show off, to wear the evidence of their skill and dance with all their neighbors late at night.