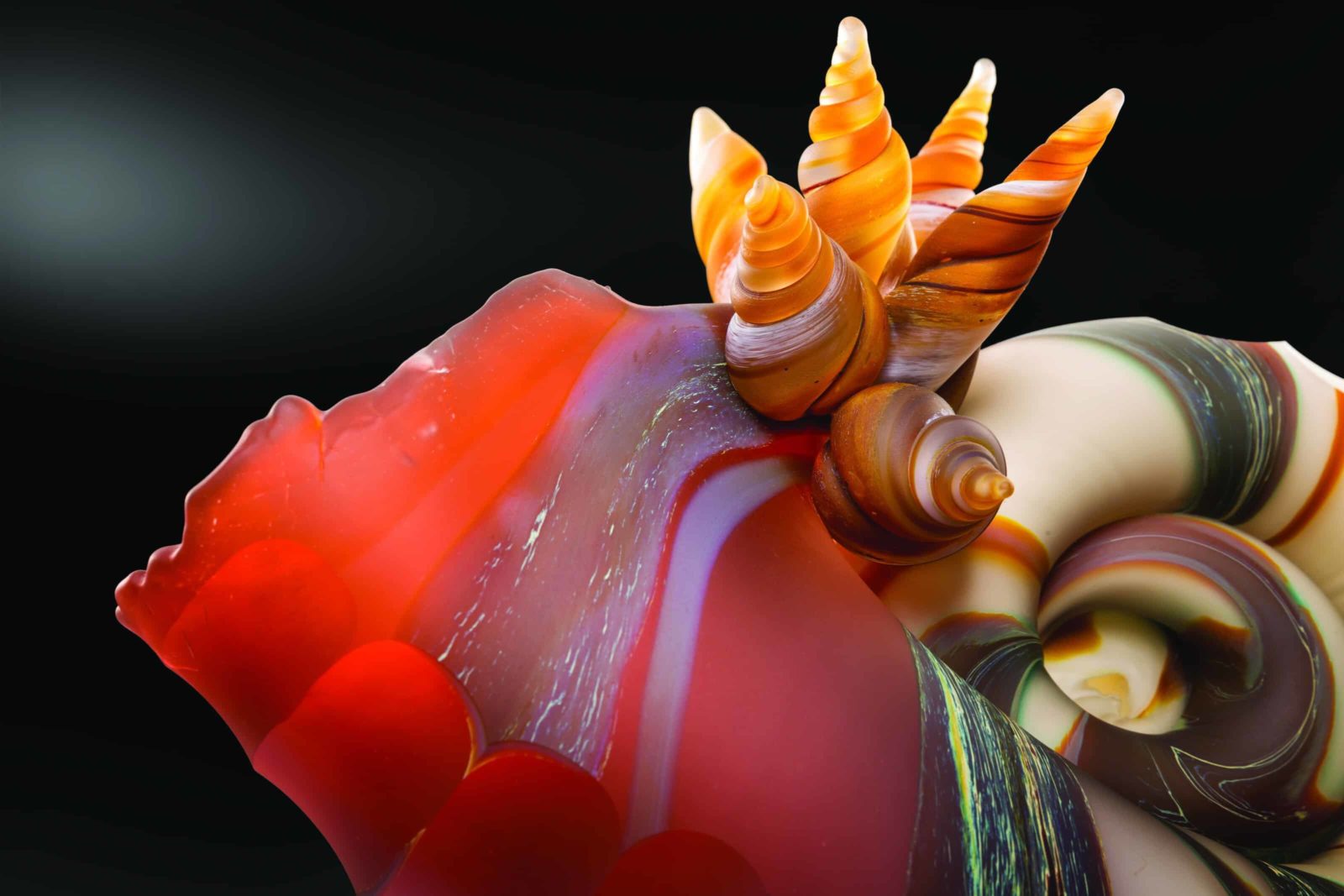

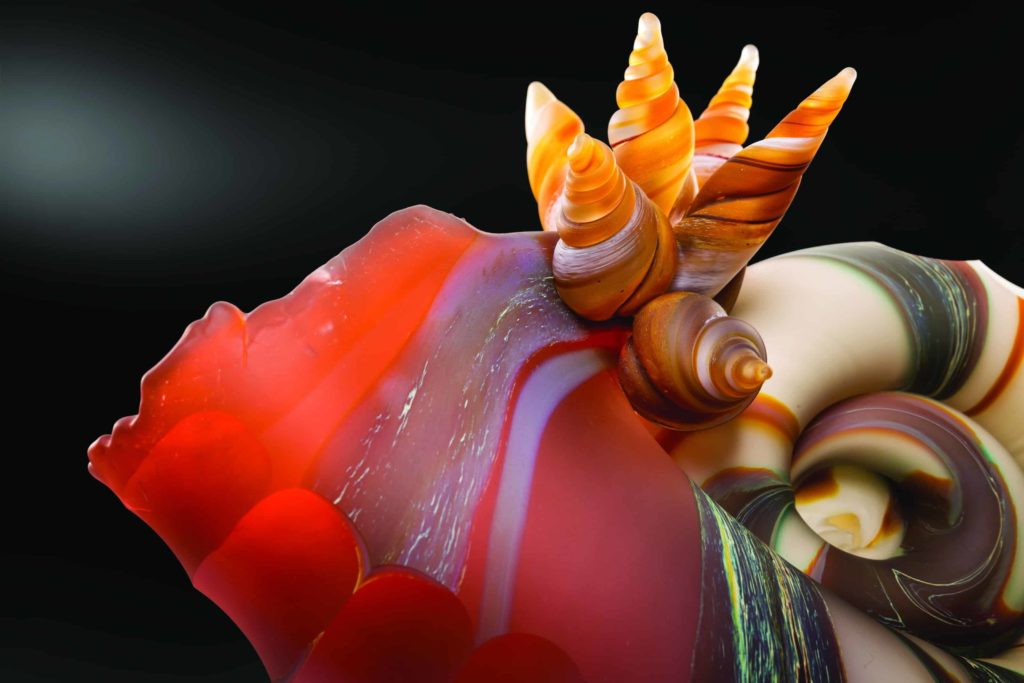

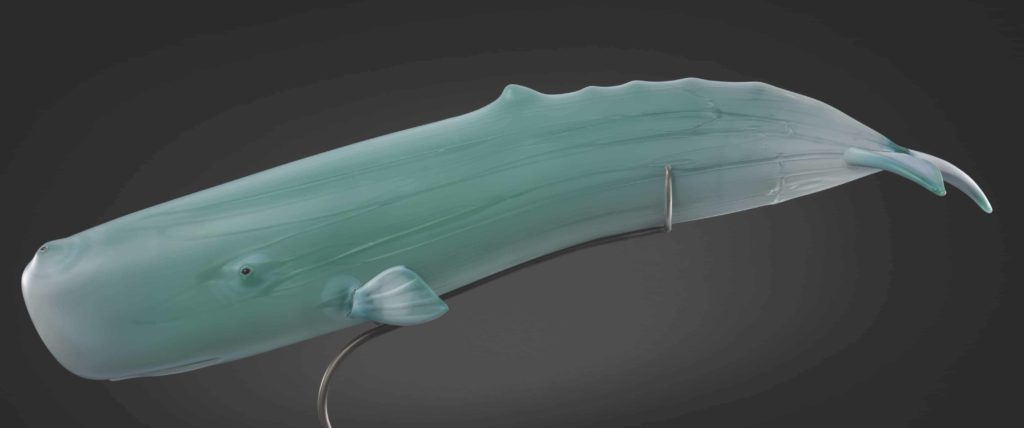

Streaked petals open like water lilies in Herman Melville’s Garden. A sperm whale dives with skin like striated ice. Barnacles cling to a shell. And they are all made of glass. Three internationally known artists — Kelly O’Dell, Raven Skyriver and Paul Stankard — sculpt plant life and sea life in a show at the Schantz Gallery in Stockbridge.

On the West Coast, Skyriver and O’Dell live and work near the ocean in Washington state, shaping sea turtles and salmon and the spiral fossils of ammonites that swam in the open sea more than 65 million years ago.

On the East Coast, Stankard has transformed paperweights into a high art, a swarm of bees in a glass globe.

“Each person brings a magical response, an intelligent response,” Stankard said, talking by phone from his studio in New Jersey.

“Glass is the most common man-made material,” he said. “It goes back 5,000 years … but only in the last 50 to 60 years has it had a fine art expectation” — not useful but beautiful, expressing an idea.

Skyriver and O’Dell are furnace workers he said, gathering molten glass and shaping it around a metal rod — they may blow a shape, pull the form while it is hot, turn it, carve it and texture the surface.

Stankard is a flame worker with a bench burner like a blowtorch. He re-melts glass rods in many colors and shapes them with tweezers and paddles to create miniature sculptures.

“I’ve learned over the years to bring detail, delicacy and workmanship,” he said. “I think at this stage of my career — I’m only 75 — I feel fortunate that I can go into the studio and re-interpret my past.”

He grew up in North Attleboro Mass. and spent summer afternoons in the woods, picking blueberries.

“I’ve always spent time out of doors,” he said.

He has always loved plants and flowers, and working with his hands. Stankard struggled with dyslexia before it was understood, and when his father transferred to Southern New Jersey, he went to Salem Community College to train as an industrial glassblower.

“There’s a rich tradition of glass in Southern New Jersey,” he said, “and the crown jewel of it is the Millville Rose Paperweight. I was fascinated by the idea that turn-of-the-century glassblowers would make paperweights.”

Workers in glass factories, many of them from Europe, would make glass roses on their own time at the end of the day. Stankard began the same way, playing on his lunch hour and working on the weekends.

Over the last 50 years, he has transformed the artform with techniques he has created himself. He is world-reknowned, Schantz said.

“I’ve invented a language,” Stankard said, “a glass vocabulary to interpret the plant kingdom.”

He wants to do in glass what a poet does with words, he said. He loves Walt Whitman’s bragadocious energy and his pleasure in making — “The narrowest hinge of my hand puts the scorn on all machinery.”

And he recognizes the joy in Emily Dickinson’s spare lines.

“I love the idea of having an aptitude,” Stankard said, “of focusing a career within a perimeter” — encapsulating flowers within a ring of hot glass.

Alongside him in this show, Skyriver and O’Dell are internationally known artists, and they are couple with a 7-year-old son, Wren.

They have established themselves in the deep glass art community near Stanwood, Wa., and they ran a recent successful Kickstarter campaign to fund a new studio they will build on Lopez Island, off the coast of Seattle, where Skyriver grew up. He is Tlingit and spent his childhood here in the Pacific and began blowing glass in high school.

O’Dell comes from Hawaii where her parents worked in stained glass and furnace glass. She and Skyriver met at the Pilchuck Glass School, an international center founded in the 1970s at the center of the young glass art movement.

There they were both students of William Morris, who brought artists from the school into his workshop as assistants, Schantz said. O’Dell and Skyriver were the youngest artists on Morris’ team before he retired.

With him they began experimenting with new textures, with ways to change the glossy and clear surface of glass right out of the annealing oven. They use a range of deft techniques — sand blasting, etching with acid — to suggest the feel of an animal’s skin or shell, a sea lion’s fur, a salmon’s scales, a sea creature under water. They may sift and melt ground glass into the surface of hot glass to add opaque hues.

“Think of sand paintings,” Schantz said.

Many of O’Dell’s creatures left the earth long ago — drops of amber, fossils in crystal, endangered or extinct rhinoceri.

Skyriver’s often live off the coast. A diving humpback whale trails a buoy and line around its flukes. Every year many whales die from getting caught in marine debris, Schantz said. Ghost nets, lost fishing nets, can float almost invisible or catch on reefs.

Among his whales, mahi and seahorses, last year Skyriver made a sea turtle, the only one like it in the world, Schantz said. His gallery helped to sponsor the work at the Museum of Glass Tacoma, because Skyriver needed space and resources beyond his studio to assemble it.

He made the flippers, the head and the shell ahead of time in his own studio, and brought his team to the museum to attach them. He and his team had to work quickly, Schantz said, within a couple of hours, and they had to keep all of the glass at 800 or 900 degrees, hot enough to attach but not melt, reheating the whole creature in a central oven like an open furnace, called the glory hole.

“With blown glass you can’t rework it,” Schantz said.

So, as Stankard encloses his blossoms and Kelly spirals her shells, Skyriver makes a final piece in one sustained movement — and the glass will keep its integrity.

This story first ran in the Berkshire Eagle. My thanks to Features Editor Lindsey Hollenbaugh. Image: Meditation in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Garden, 2016. Photo courtesy of Paul Stankard and Schantz Gallery