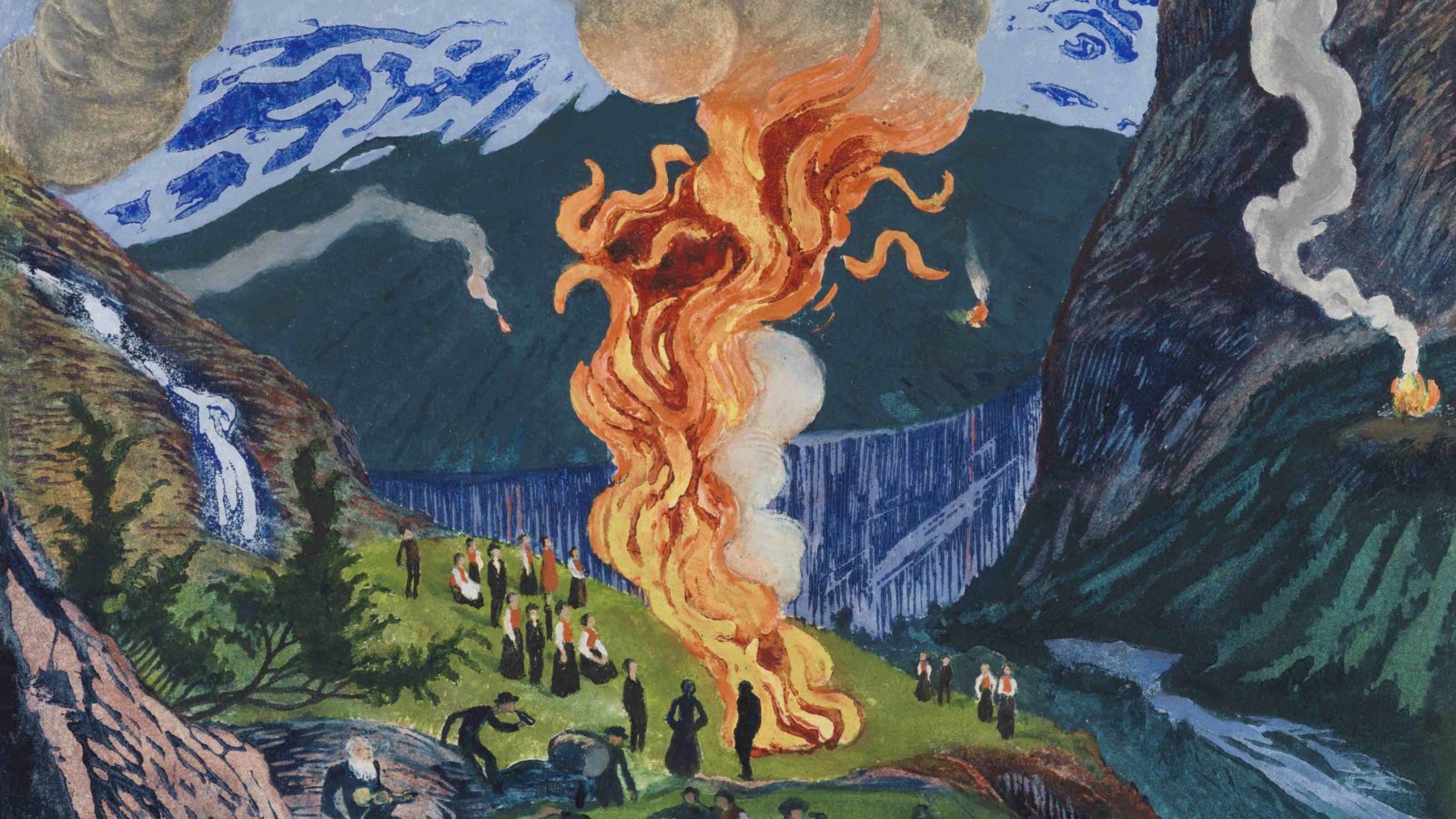

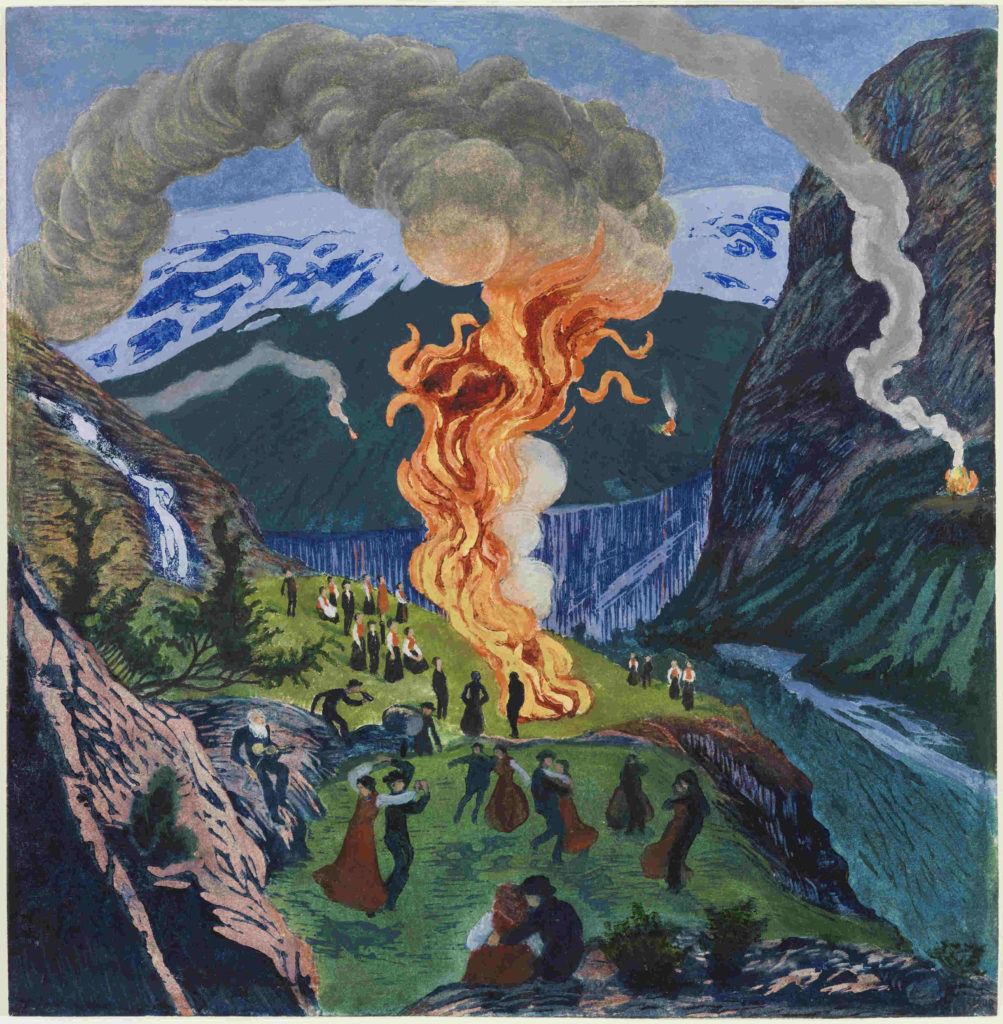

It’s summer solstice, and the bonfires are lit. People from up the valley are piling tall cones of green branches. The flames churn golden and flow downhill over a glacial outcrop and coil like a dragon around the embers.

Distant fires are burning on the steep hillsides. In this high valley in Western Norway, the snow on the ridges is reflecting the sky — and on the longest day, it is still light near midnight. Men and women are dancing in the grass in a dell above the lake, where a waterfall rushes down to the shore and firelight glows on the water.

Nikolai Astrup paints them as though he is standing on the slope, listening the Hardanger fiddle carry across the dell in the summer night. The traditional instrument has eight strings — the four on an Irish or American fiddle, and four below them to thrum low under the melody line.

In time for midsummer, the Clark Art Institute opens a retrospective of more than 20 years of Astrup’s work, shown for first time in North America. He is loved in his own country and rarely seen outside it, said Olivier Meslay, director of the Clark.

“For me, it was a revelation,” he said.

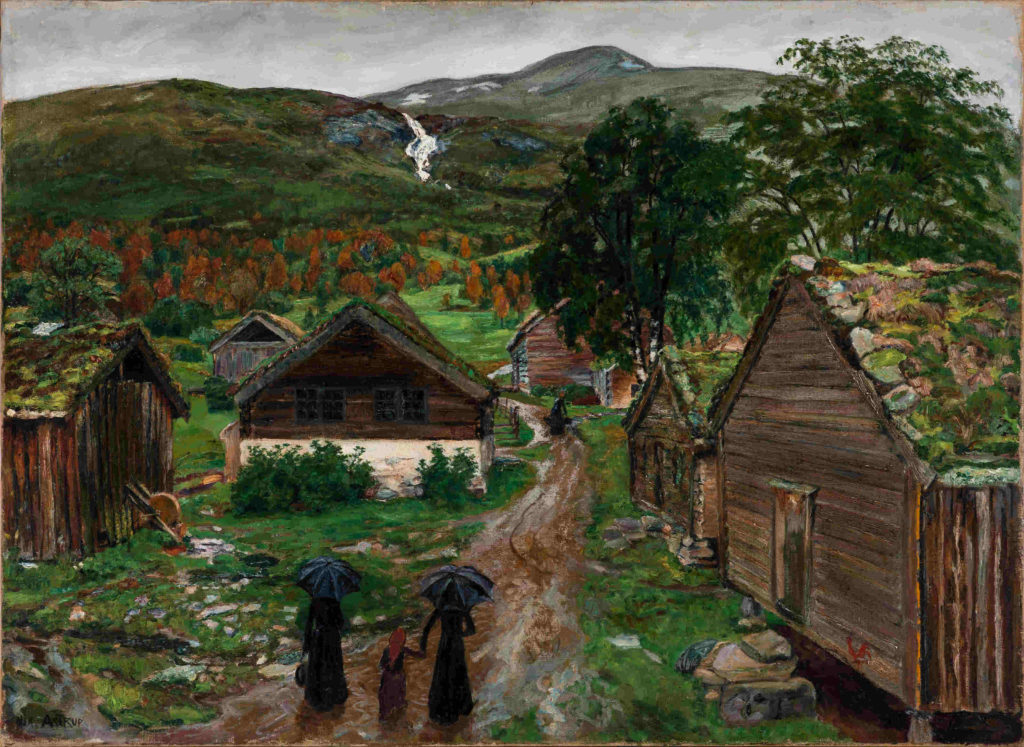

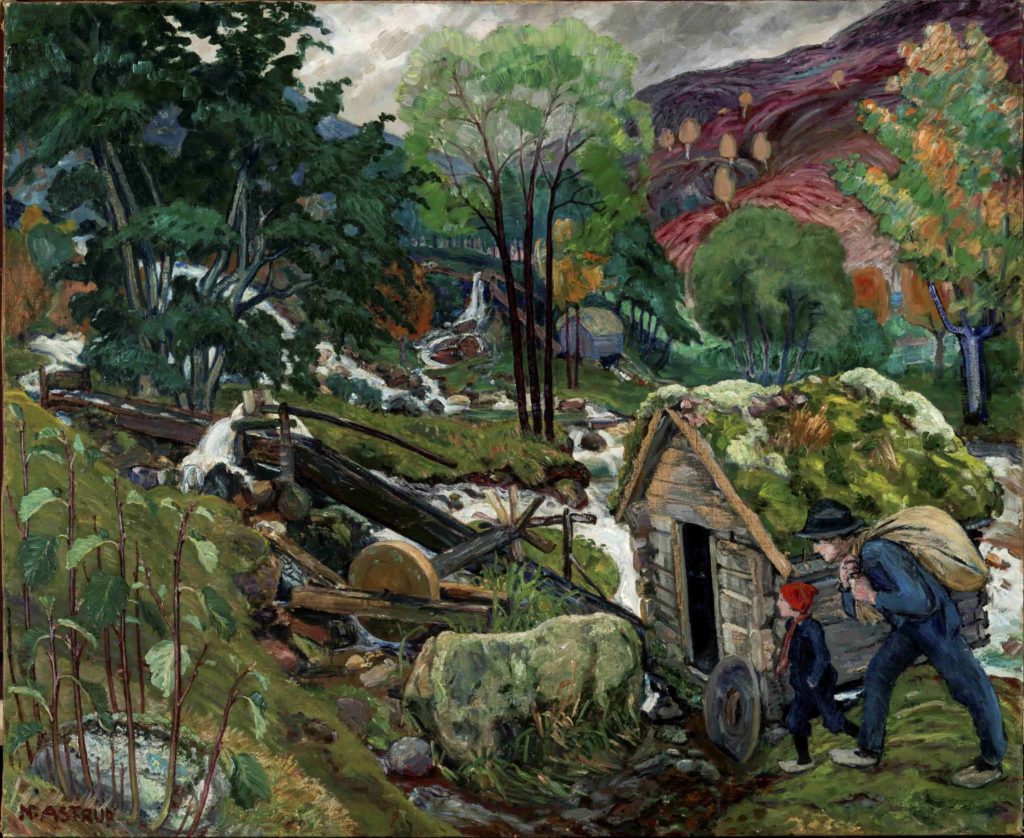

Norwegian artist Nikolai Astrup's painting shows the Parsonage, his childhood home. oil on canvas, KODE Art Museums and Composer Homes, Bergen. Image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

Kathleen Morris, the Clark’s director of exhibitions, introduced him to Astrup’s work, and he began to search for Astrup’s paintings in museums and private collections in Norway.

He found an artist coming of age at the height of Modernism who lived in a farmhouse with a turf roof. Astrup seems to overturn conventions and expectations. He and his wife traveled in Europe and North Africa, and he studied in Paris and kept up with avant garde publications. And he stood at the center of the movement for Norwegian independence, arguing passionately for folklore, pagan ritual and the conservation of native plants.

“He was an intensely inquisitive and intellectually disciplined man,” said MaryAnne Stevens, guest curator of this show, independent scholar and former Director of Academic Affairs at the Royal Academy in London.

She sees a clear eye in his work — in the detail of veins on a leaf and light reflected in water or glass — and the same ambition and care in his terraces of birch and cherry trees, the gardens of beets and potatoes, rhubarb and wildflowers he and his family would grow and preserve for the winter. He immersed himself in grafting and cross-breeding and pollarding, and preserving wildflowers and pollinators.

Astrup was born in 1880 and grew up here, in a small town in the region then called Jølster, above Jølstravatn lake, on the Southwest coast. He was one of fourteen children said Alexis Goodin, Curatorial Research Associate, Clark Art Institute. His father was a Lutheran minister and sometimes severe.

But Nikolai went to art school and traveled as a young man. He knew Berlin and Paris — he saw Toulouse-Lautrec paintings at the Salon des Indépendants and Ukiyo-e prints in Paris galleries and Constable at the National Gallery in London, and he followed Cézanne and Van Gogh in contemporary journals. He knew Kandinsky’s landscapes, half-abstracted in bright, broad strokes of color.

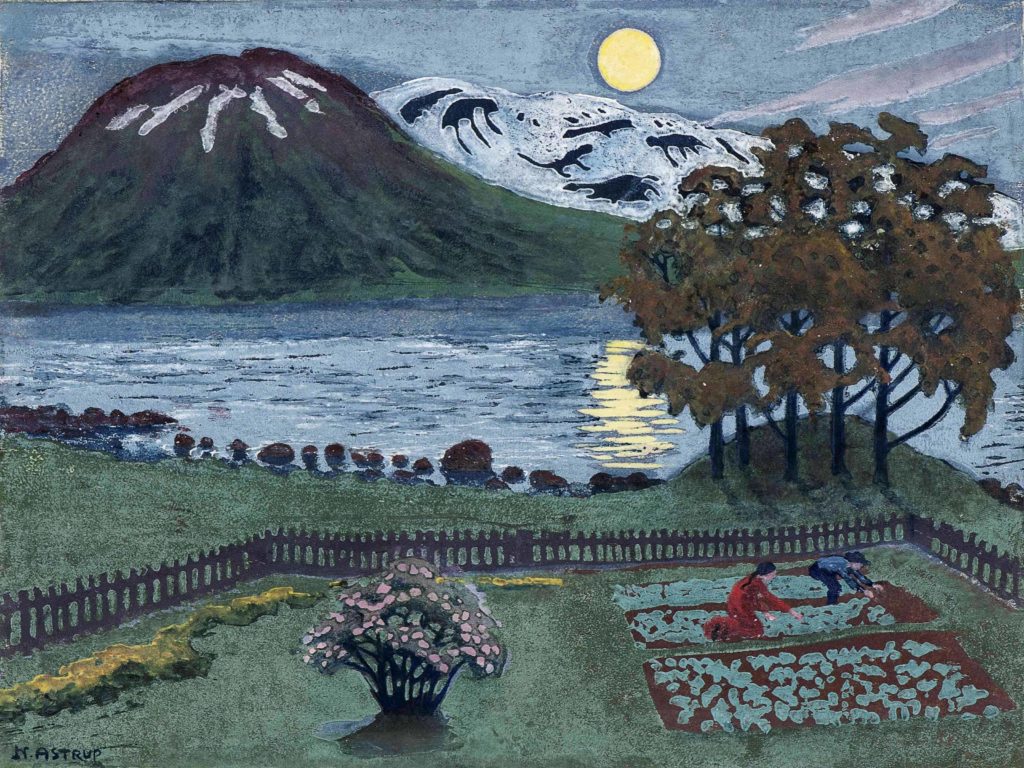

Nikoli Astrup created a woodblock print of his painting, 'The Moon in May, showing the garden on the lake shore at night. 1908 pring with hand coloring, collection of Nicolai Tangen, Oslo

He was 25 when Norway gained independence from Sweden, in 1905. For the first time since 1397, Norway stood apart from both Sweden and Denmark, Goodin said. An earlier generation had led a sense of pride in Norwegian culture. Henrik Ibsen and Edvard Greig were known around the world. Ivar Aasen created a dictionary, and Norwegian language in schools and newspapers. But Norwegians had been closely assimilated with their neighbors for centuries.

“Danish was the national language,” she said.

In Astrup’s generation, a movement was growing to define a Norwegian voice in art and music, writing and theater. While he was appearing in his first solo shows in Oslo, Sigrid Undset was making her name as a novelist. (She would become a Nobel Laureate in 1928, the year Astrup died.) Cora Sandel, one of his fellow students at Harriet Backer’s art school, was painting and writing novels in Paris, and Olav Duun was writing epic fiction in the new Norwegian language at Namdalen, up the coast from the Astrups’ farm.

Norwegians were celebrating images and folk artforms that felt uniquely their own, Stevens said. And Western Norway, with its mountains and glaciers, waterfalls and meadows, became a center for the movement.

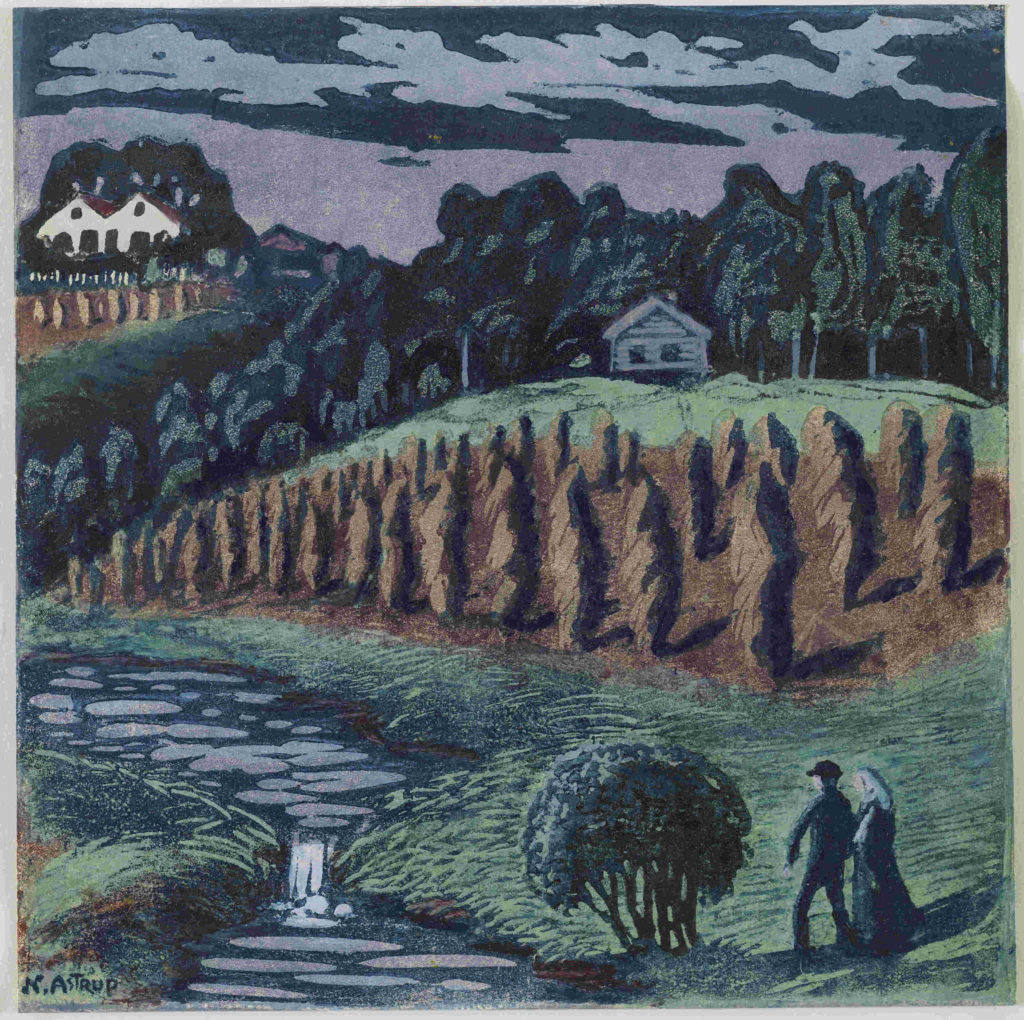

Astrup paints with an intense sense of place, she said. His work can vary widely in tone and mood and atmosphere, even when he has printed them from the same wood block. He captured the fjord-like lake below his dooryard in subtle shades of northern light, after the rain or in the glow of northern summer nights when the sun hardly sets.

He lived most of his life along that lake shore, said Tor Martin Leknes, director or art for the Museums of Sogn and Fjordane including Astruptunet, the museum that now preserves Nikolai and Engel’s house and gardens.

In 1907, Astrup returned to Jølster, and by now he was engaged to a local woman, Engel Marie Andersdatter Sunde. They married just before Christmas. Engel was a textile artist in her own right, Goodin said — she printed on cloth and embroidered, and she would work with Nikolai to preserve folk art and culture in the region. (Goodin will give a talk on their partnership and their relationship later this summer.)

Nikolai Astrup's painting recalls his wife, Engel, picking rhubarb in their garden. Oil on canvas, KODE Art Museums and Composer Homes, Bergen. Image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

Together, Engel and Nikolai began to rebuild and transform the old parsonage house where he had grown up. They saved and renovated old buildings from farms nearby and linked them with walkways and garden beds.

On the lakeshore, their home grew into a homestead, the old clapboard house surrounded by small barns with living roofs — earth over birch bark seeded naturally with grasses and wildflowers. They give natural insulation in the cold. Goodin said.

The Astrups lived on a hillside so steep, Nikolai built terraces and pathways so he and his family could till their garden. He planted fruit trees by hand, she said, and worked to build up the soil. Family and friends would gather on summer nights and sip Engel’s rhubarb wine with long views of the lake.

(The Clark will have a rhubarb tasting on August 1 with Darra Goldstein, acclaimed food writer and scholar and Williams faculty emerita in Russian; she will talk about Norwegian traditions from her travelogue and cookbook, Fire + Ice, and serve a sparkling summer cooler and dessert made from rhubarb, in honor of the Astrups’ garden.)

Through the next 20 years, Nikolai would paint his own home, the house and the lake, the mountains and boreal forest, in many different ways. The show follows his work as it evolves over time. Goodin traces the influence of Japanese printing as he experiments with his own.

In his largest scale wood block prints, a bright clump of foxgloves stand front and center, tall stalks and bells of flowers. They grow in disturbed ground, Goodin said, and two tree stumps show the disturbance of men, but the scene is a rich late summer tangle of green. Quietly in the middle ground, two girls come into the clearing with baskets to pick wild blueberries.

The scenes begin to shift in perspective. Moving around a corner, Goodin comes to a new body of work and traces an artistic crisis in its bold, blurred lines. In Astrup’s lifetime, even in his years in Paris, the Impressionists of his childhood are giving way to Modernists, and Goodin sees the influence of his contemporaries in his work.

Modernism is usually an urban and industrial artform and way of thinking. It grows from the argument that man can control his surroundings through science, technology and the shear weight of manufacturing.

She sees Modernist elements here in the ways he paints one scene from different perspectives, looking from above, scrunching a hill int the foreground, almost tipping the ground forward out of the frame.

“He will look at one subject from a variety of viewpoints and put them together in a non-linear way,” she said, “and disjoint the scene.”

In these years, he was often struggling, she said, mentally and physically. He wanted to experiment in new forms far from the realistic and quiet landscapes that had brought him early success. And as he was looking for direction in his work, his health was failing. After years of illness, Nikolai died in 1928, at 47, leaving Engel with eight children to care for. She would live until 1966, just before the new year.

The show pauses in that moment … and then moves into a room pulsing with light. Here are the solstice fires in wide open scenes wound around with myth and magic realism. Here is a fertility ritual in high summer, painted in broad strokes and vivid color, and bringing with it love and new growth, and music and ideas persisting through centuries.

Flame lights a hillside above a lake in Nikolai Astrup, Midsummer Eve Bonfire. Woodblock before 1917, private collection. Image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

In these scenes, natural elements take on subtle forms. A dancer flings out his arms, and the firelight throws his shadow onto the boulder behind him, giant-sized. A pollarded willow reaches out to the evening sky. A mountain in the snow transforms, and a woman is lying on her back with her knees drawn up, clear on the horizon.

“He infuses his scenes and landscapes with references to the myths,” Stevens said, “… and we have to winkle them out.”

In a summer field, poles are holding grain to dry in the damp climate — and with another look they turn into tall, lean, rangy beings, lanky and russet gold. They are walking away across the field, and one turns to look back over a shoulder.

Astrup was creating a visual language, she says, peopling the land with spirits and from folktales. He was drawing on animistic beliefs centuries old, that a tree or a mountain, a river or a fire can have a soul.

And the solstice fires burn with a visceral energy. They fascinated him, Goodin said.

He was never allowed to go to those revels as a boy. His father, the Lutheran minister, had disapproved of the movement and the music, the pagan influence and the unrestrained glee of spinning on a hillside in a summer night. The Hardanger fiddle was banned in churches even into the 20th century, she said.

On midsummer eve, the Clark will bring one here. The low, deep hum will rise at the foot of Stone Hill, and a bonfire will cast a glow on the water of the reflecting pool.