In a garden in Paris, a woman sits drawing the petals of hyacinths. She is shading in curves and striations, down to the folds along the tips and the green nubs of calyxes. She has had time to come to know them well, as they bloomed in the Tuileries in warm weather and in greenhouses at Nöel.

In 1735, Madeleine Françoise Basseporte became the first woman ever to become the official painter of the Jardin du roi (the King’s garden) for Louis XV.

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte's drawing of hyacnths, narcissus and a moth in her 18th century album of flowers. Drawing in the collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, press photo courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

Hyacinths were newcomers to France in her time. They came to Europe from Southwestern Asia and the Eastern side of the Mediterranean, from Syria, Lebannon and Turkey, a relative of plants as far-flung as asparagus, agave and bluebell.

‘Drawings can be spontaneous … and they can give a rich and layered understanding of Paris.’ — Sarah Grandin

Her meeting with one is a rare convergence in more ways than one — in the 1740s she is an artist, and she makes her living this way.

And this winter, almost 300 years later, a conversation in a Paris cafe has led her drawings here. The Clark Art Institute offers Promenades on Paper, a newly opened exhibit of drawings from the Bibliothèque nationale de France (the national French library).

Drawings can be spontaneous, said Sarah Grandin, Clark-Getty Curatorial Fellow, walking through the exhibit before opening day. And they can give a rich and layered understanding of Paris, from palaces to street vendors.

The show takes its name from the rise of the strolling sketcher, le flâneur — artists like Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, who would go walking with a guidebook in his back pocket and draw in the margins.

The 17th century was a time of massive change in France, a time of new technology, rapid growth and the unrest that led to the Revolution. The city was expanding, and artists were loitering on city streets to take in the action.

Jean-Baptiste Hilair sketches gardeners picking fruit in the Orangerie in the Jardin des Plantes. Press photo courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

A treasure hunt through the archives

Grandin has gone to Paris with Clark director Olivier Meslay and curators Esther Bell and Anne Leonard to find them. Grandin has joined a team of curators from the Clark and the BNF to comb through a collection of more than 15 million elements in the library’s collections — prints, photographs, cards, newspapers and many more.

“We don’t know what we have,” she said.

But they have had a luxury of depth and focus, and a chance to find and show work that has never been shown before, Many of these drawings have never received this kind of attention, Grandin said, and this is first exhibit of this period ever put up. The BNF has shown drawings from the 17th and 19th century, but never 18th century.

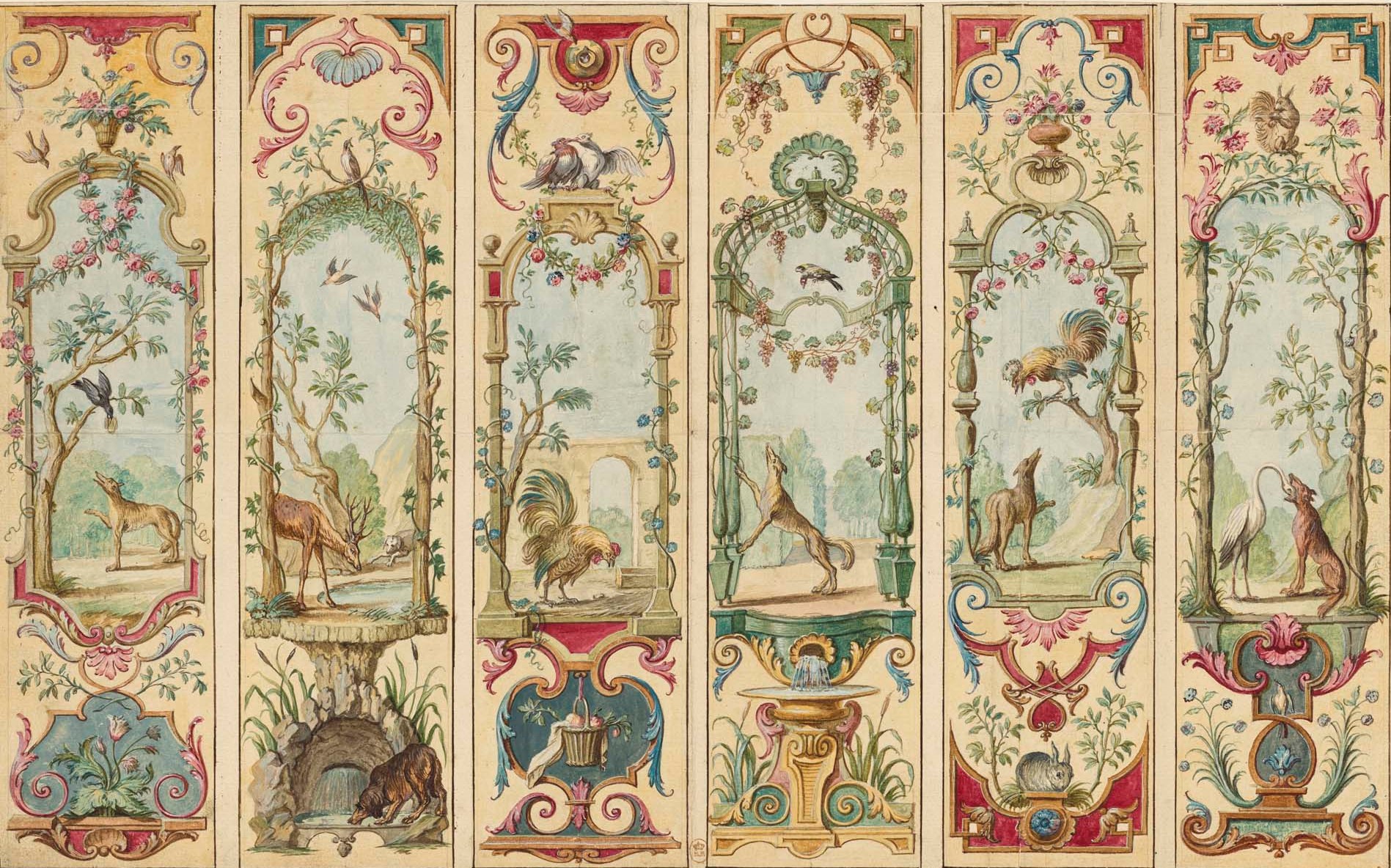

A drawing for a proposed folding screen shows twining vines, birds and animals. Press photo courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

Many of them even the BNF curators may never have seen before. Maybe a third of those 15 million works have not yet been fully catalogued, said Corinne Le Bitouzé, deputy director of the Département des Estampes et de la photographie (Department of Prints and Photography) of the BNF. She calls this collection of mysteries La Matière.

La Bibliothèque national de France has a mission, she said, to preserve what might otherwise have been destroyed.

The eye of the beholder

Drawings can act as documents of time and place, Grandin said, and they can hold layers of story. Basseporte was drawing her hyacinths in a time of curiosity in her country, and botanical collection … and colonialism. Basseporte corresponded with scientists who travelled widely, and she taught scientists and artists, women as well as men.

She knew Carolus Linnaeus, the leader of one of the best known systems for classifying plants and animals around the world, well enough to write to him often and and share inside jokes.

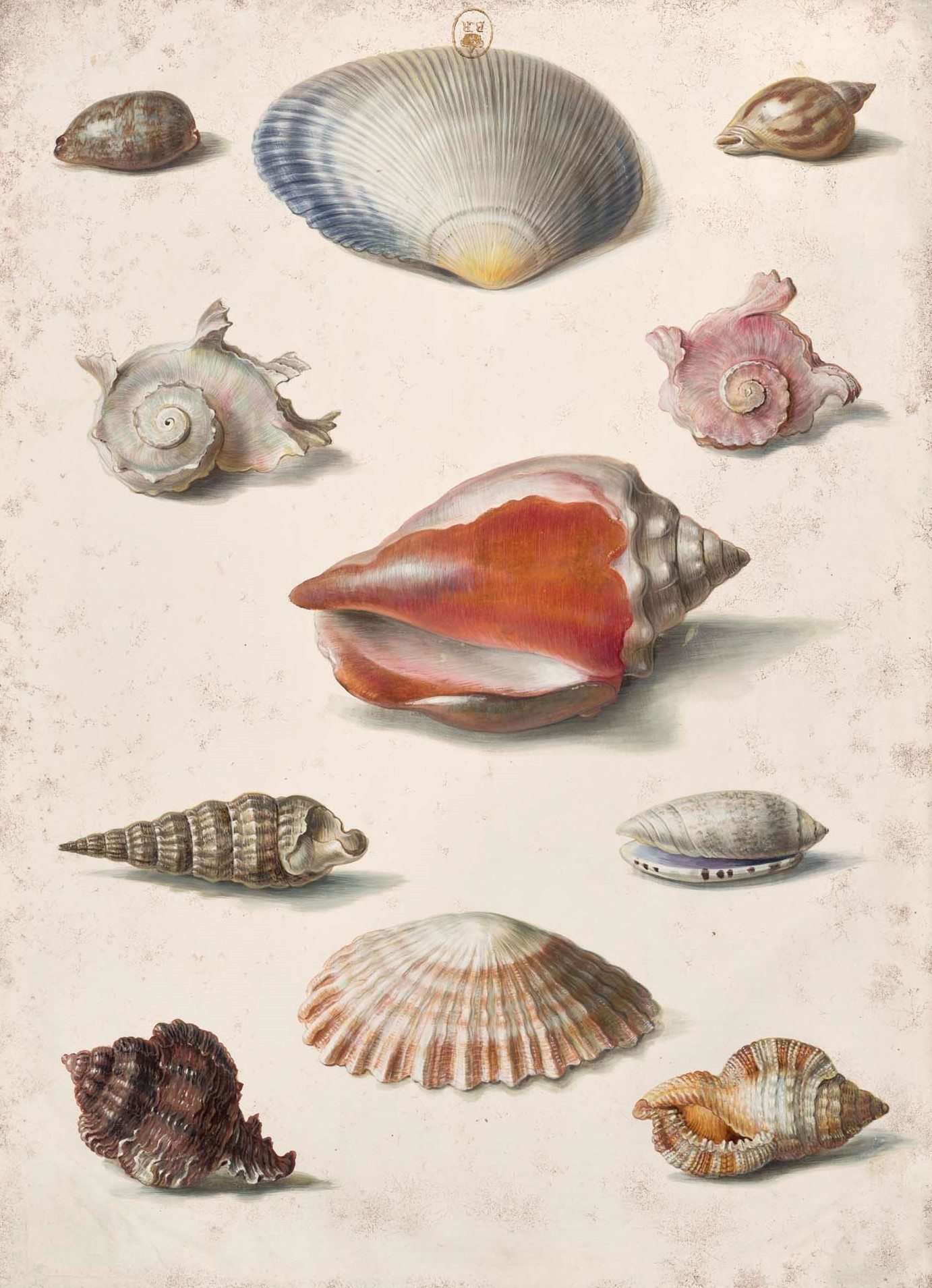

Artist Émelie Bounnieu illustrates many kinds of shells in a drawing in the collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Press photo courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

She drew flowers to preserve their details quickly at the height of their bloom. Their colors stand out vividly in gouache on vellum leaves — morning glories and johnny-jump-ups, white lilac and hellebore, butterflies and moths.

Basseporte held her position as garden artist for 45 years, Grandin said. The king supported her work, as she kept a close eye on the bulbs and blossoms and insect life in his 18 acres of gardens along the Seine. And few records give glimpses of her life. Her collection was seized by the revolution and put into the Museum of Natural History, and rare examples of her work have come into the bibliothèque afterward.

“We don’t have a book dedicated to her,” Grandin said, “through some scholars are researching her life and work. Painting from nature was study available to a woman when historical subjects were not.”

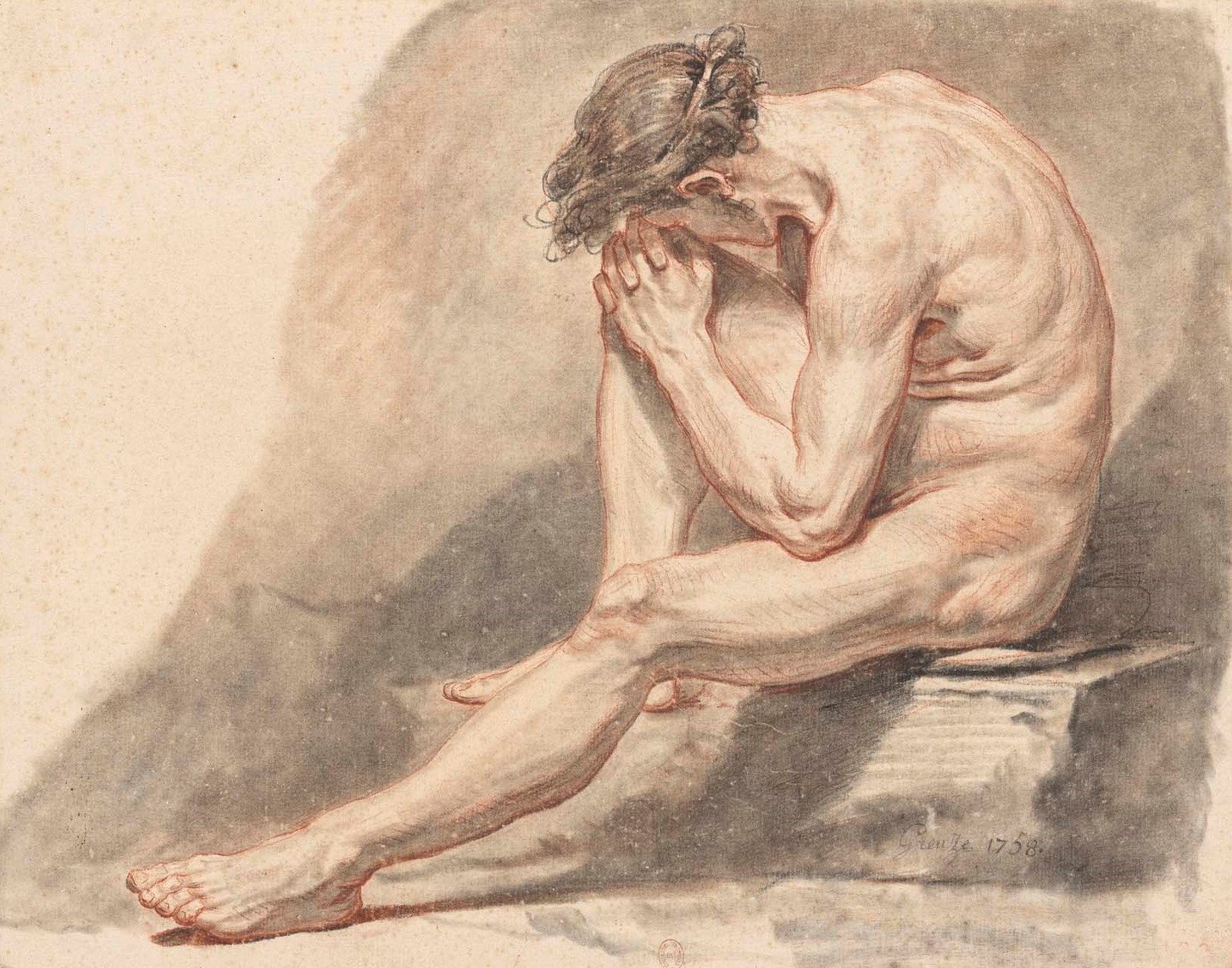

Women were also not allowed to draw from models. Women artists were barred from studying and drawing people from life, Grandin said. The Academie Française, one of the country’s chief centers of learning, accepted only four women a year and would not allow them into the classroom with human models.

Women found their own means to study, she said, some through the workshops of fathers, brothers and uncles. On the next wall, Émelie Bounnieu offers detailed views of minerals and shells.

“Her father was a painter,” Grandin said, “and during the Revolution he was the guardian of the print cabinet.”

So Bounnieu could see and study works of science, and her father’s influence may have brought her drawings into this collection.

‘We can see paper as a site of possibility unfettered by physical constraints, where imagination can run free.’ — Sarah Grandin

And drawings can show not only close observation and curiosity, but dreams. Grandin shows a series of drawings envisioned projects. Étienne-Louis Boullée’s vision of a cenotaph for Isaac Newton rises in a sphere like the night sky.

“We can see paper as a site of possibility unfettered by physical constraints,” she said, “where imagination can run free.”

These are some of her favorite drawings in the show, she said — they are whimsical and moved by a love of event and spectacle. Here is a theater, a proposed opera, here a set design for the Comédie Française, and here are costume ideas, some made real. A Norwegian nobleman prepares for his entrance in Ernelinde, and the mythological figure of Ixion lies bound with snakes onto a Wheel.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze draws a man sitting wiht his head resting on his knee. Press photo courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

Drawings could become illusions, Grandin said. By the 1700s, they could even become three-dimensional. She has found a zobrascope, a device like an early stereopticon for giving a sense of depth to a two-dimensional work, and a camera obscura.

They could also hold an almost journalistic realism. Around various corners, artists capture street scenes and current events. Claude-Louis Desrais’ sketches of Les Cris de Paris show street vendors from a man selling kindling to a woman turning a hurdy-gurdy.

Hubert Robert shows the high vaulted stone arch of the stables at the Villa Giulia rising three stories high. Horses stand on the ground floor, still loaded up with burdens, and a ladder runs up to a loft of loose hay.

In contrast, designs for possible artwork in Rococco — “a voluptuous, effervescent, asymmetrical embrace of nature,” Grandin said.

‘It’s a process of discovery. … Sometimes we found things we didn’t expect.’ — Sarah Grandin

Drawings cover a wide range in background and place and time. Finding them, she said, became a kind of grand treasure hunt through the archives. In all those 15 million works, a few hundred thousand are drawings — a large number, but a small percentage.

The collections may have thousands of drawings for every hill and river and corner in Paris and through the country, all organized by place, so that she once found a drawing of a tavern tucked between maps.

“It’s a process of discovery,” she said. “… Sometimes we found things we didn’t expect.”

The curators would look through boxes sectioned by artists, kings, media. One held prints and drawings from 1715, Grandin said, and maybe three out of a hundred would be drawings. She and her team chose to focus on drawings because the BNF wanted to explore this area of their collection, and because often very little is known about them. Prints can be rare, but can they can exist in other collections — drawings are unique.

And they can hold depths of local knowledge. Saint-Aubin drew in the margins of sales catalogs from auctions — precise thumbnail sketches of artworks with the names of the artists and details. He captured a detailed record of the art world in his time and the people and the work he saw every day.

Couples walk in the park in Beaumarchais. Press photo courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

He also sketched also personal and subjective scenes. Grandin invites close inspection of a small, bright painting of artists in watercolor and ink on vellum, from a May exhibition. Young artists show their work outdoors on a spring morning.

“He was in the thick of things and in the margins,” Grandin said.

In heightened times, drawings can move through daily experience to life-changing and literally visceral. This was the century of Napoleon’s campaigns and the Revolution, when the guillotine operated in the Place de la Grève, leaders turned on each other, mobs sacked palaces and the Tuileries burned down. Artists saw the violence of the uprisings up close.

And sometimes the BNF has preserved more than ink and charcoal. Drawings can be close to daily life — carried in a pocket, jotted down at the counter of a tabac — and even closer than that, Le Bitouzé said.

In this show, Grandin and her fellows have included a portrait of Jean-Paul Marat, the revolutionary leader famously murdered in his bathtub. He was a journalist as well as a doctor and an artist “at a time when artists could be exposed (by Marat himself, most notoriously) as counter-revolutionary.”

Seeing him, Le Bitouzé shares a memory. Among the BNF’s collections of newspapers and millions press photographs, she said, they have copies of his journal L’Ami du Peuple (the Friend of the People) — daily newspapers more than 200 years old. And one copy preserved at the BNF is marked with his blood. It may have been in his rooms when he died.

Drawing as domination

Drawing can also act as conquest, Grandin makes clear. In the final room of the exhibit, the Clark and the Bibliothèque present the work of artists and engineers who traveled with Napoleon in the forced occupation of Egypt in 1798.

The Bibliothèque has some 800 drawings previously unknown to the public and other art historians, Grandin said. Napoleon meant them to be reproduced in 23 volumes of a ‘Description of Egypt’ — huge volumes. The exhibit makes clear the costs and violence in this approach.

“He was conquering Egypt both on the ground and through paper,” Grandin said.

‘(Napoleon) was conquering Egypt both on the ground and through paper,’ — Sarah Grandin

Napoleon came with engineers, scholars, 150 people, Grandin said — map-makers and archaeologists were leading digs that were not sanctioned by the leaders of Egypt, and scholars were making off with objects of cultural heritage centuries old. They seized many objects, and later the British took many of them from France, and many are still in the British Museum — like the Rosetta Stone.

Here an Abyssinian bishop looks out of one portrait, a leader of the Ethiopian church. He stands tall, shoulders open and expression calm, wearing a black turban as a Coptic cleric would. Beside him, in another portrait in a brighter room, Amir al-Hajj holds prayer beads and sits in the light of arched windows. He was an officer who led caravans for the pilgrimage to Mecca.

These drawings can be accomplished and beautiful, Grandin said, and in some ways the aspirations of the artists may have been hobbled by the military and colonial practices they are implicated in. In drawing another country without taking time to know the place or the people, an artist may reveal his own lack of knowledge.

“To come in and ‘correctly’ depict monuments from another culture is incredibly problematic,” she said, “and we have tried to address that.”