On a winter night, a man in a wool sweater, knitted hat and glasses applies ink in a film of color. He is adapting easily to its thickened texture in the cold. Artists and printmakers are standing around a limestone block, and sheets of paper are hung carefully on the walls and spread out to dry.

In an etching, a collage of boys’ faces overlie beams and bolts and a tunnel arch. The background is highlighted in red and yellow, rubbed like old paint on cement.

In a lithograph, two women are holding each other as though they’re dancing, lean and muscled in loose orange and saffron dresses. Light on their dark skin seems to show the strength in their arms. One looks out wearing sunglasses.

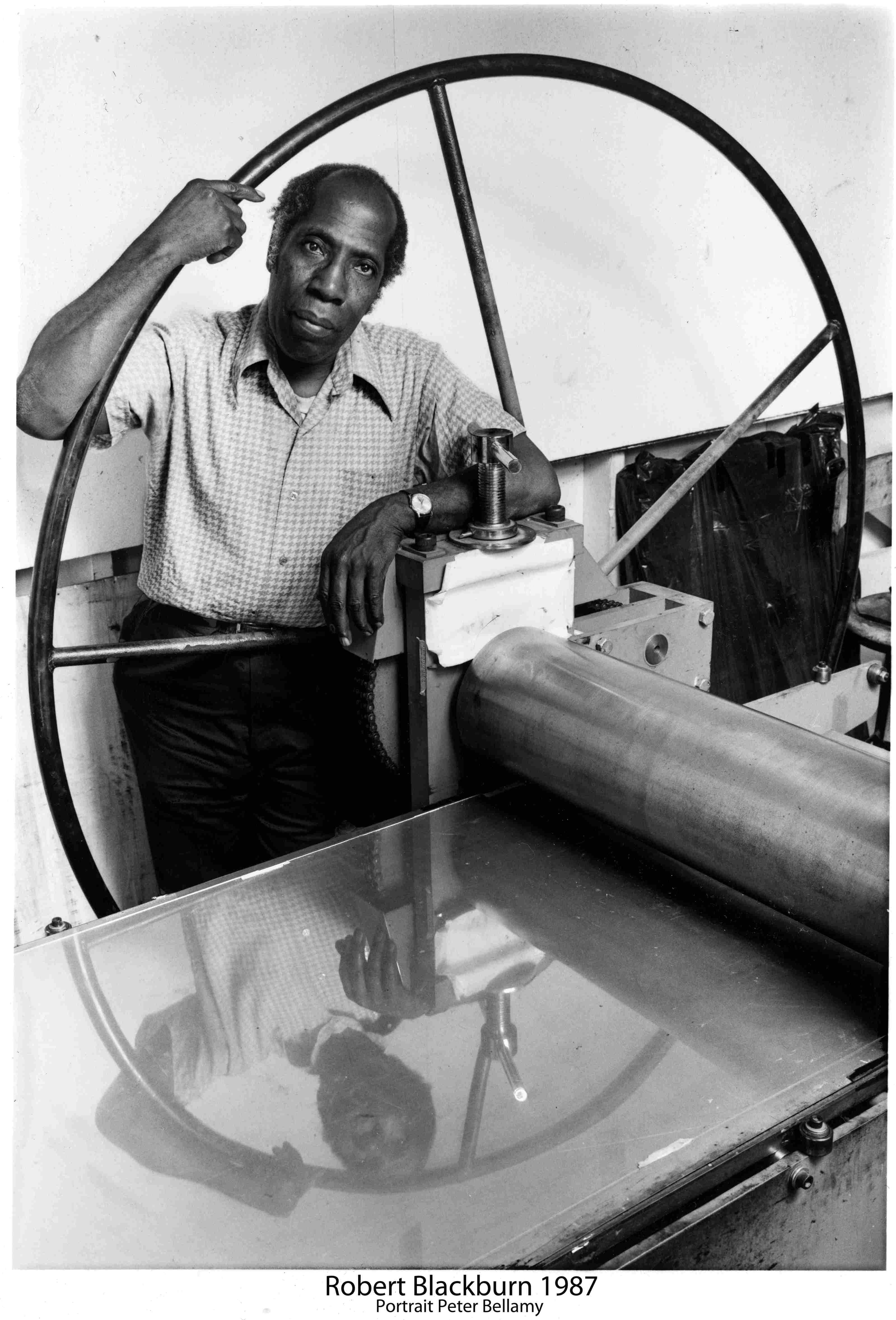

In 1947, on West 17th Street in New York, Robert Blackburn founded the oldest artist-operated and directed printmaking workshop in the country (in the words of Cherokee artist Kay Walkingstick, introducing a Blackburn exhibit at the Bronx River Arts Center and the Hillwood Art Museum in 1992).

It was an open and experimental place, where he could grow his own art — and he could grow a community of artists in New York and around the world. It was an upstairs loft where young painters could find equipment they had no access to.

A nationally known artist like Romare Bearden might spent a Saturday working on an etching like The Train. South African film-maker Dumile Feni, who had created a monumental 40-foot work at the UN and represented his country at the Sao Paolo Bienniale, pulled prints for Ruth First — Lilian Ngoyi.

Robert Blackburn's lithograph, Refugees (aka People in a Boat), 1938, shows a group of men rowing a crowded dinghy at night. Press image courtesy of the Hyde and the Collection of NCCU Art Museum, North Carolina Central University, Gift of Christopher Maxey

In that congenial room, Blackburn developed lithography and printing as an artform, said Jonathan Canning, curator at the Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, N.Y. Blackburn influenced ideas of printmaking across the country and around the world. He ran the workshop for almost 60 years in his lifetime, and he made sure it is still running almost 20 years after he died.

On January 29, the Hyde welcomes his work and his story in Robert Blackburn and Modern American Printmaking, curated by Deborah Cullen-Morales and organized by the Smithsonian.

Robert Blackburn developed lithography and printing as an artform — and influenced ideas of printmaking across the country and around the world.

“He’s an artist in his own right,” Canning said, “[and] he’s very influential as a teacher and organizer of a printmaking studio in which he works alongside and brings on artists …”

Some of those artists are very well known, he said. And they might not have worked in the print medium without Blackburn’s influence, and without the workshop he started when he was 27 years old.

A revolution in print

Lithograthy begins with a smooth limestone block. Draw with grease crayons or a thick dark liquid — dampen the surface and then roll printer’s ink over the stone and the ink will only stick to the greasy surface. Set damp paper on top and run it through a press, and the ink will print to the paper.

Blackburn first discovered it through programs at the Harlem Community Arts Center. “Romare Bearden would drop by … and Richard Wright … Jake Lawrence, Sarah Morell, Norman Lewis used to come up and have rap sessions. As a matter of fact it was a real center of the visual arts,” he recalled (in a conversation with artist Camille Billops and Jim Hatch on December 1, 1972, from the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop.)

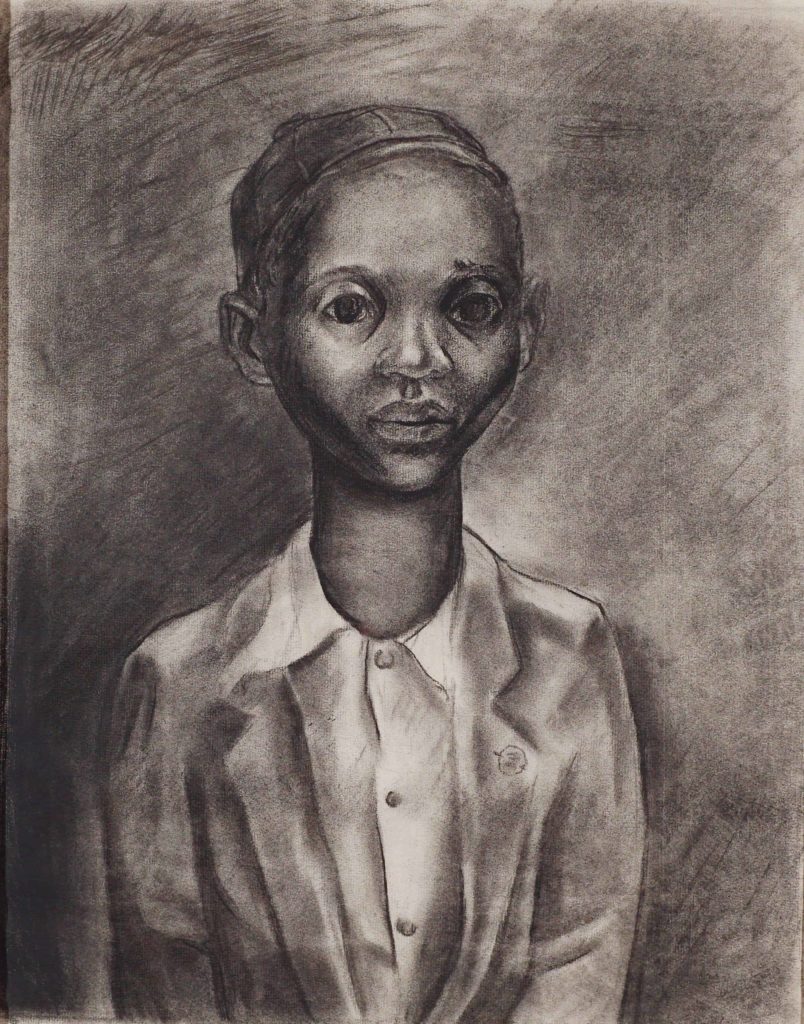

This was the 1930s, the height of the Harlem Renaissance, and the arts center drew artists, writers and dancers working with WPA. Blackburn was 13 when he first came there, he said, and he was the youngest — he knew one or two young teens there, mixing with artists and writers like sculptor Selma Burke and Langston Hughes and Claude McKay.

“He was in high school when he was meeting these WPA artists,” Canning said, “and I think one of the earliest works in the exhibition, he’s about 19 [when he made it], and that’s just extraordinary.”

Blackburn’s own art

As the Depression and World War II shook the country, Blackburn took art classes after school and work and won a scholarship to study at the Arts Students League. His early prints show the influences of Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera, and of social realism, Canning said.

Blackburn imagined clear scenes, showing people involved in physical energy and hard moments in their lives. In Refugees (aka People in a Boat), powerful people hold close together in a wooden dinghy low in the water. Blackburn’s parents had met on a boat coming from Jamaica.

‘Romare Bearden would drop by … and Richard Wright … Jake Lawrence, Sarah Morell, Norman Lewis used to come up and have rap sessions. As a matter of fact it was a real center of the visual arts.’ — Robert Blackburn

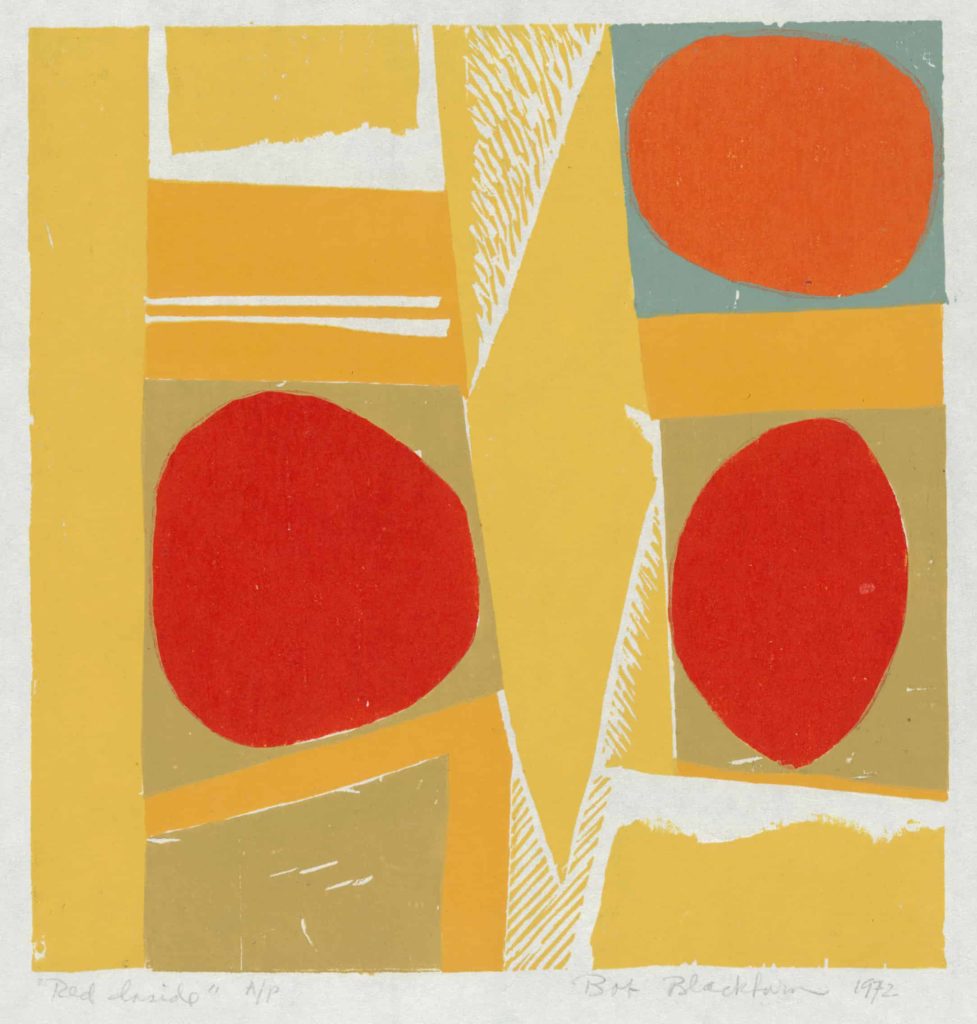

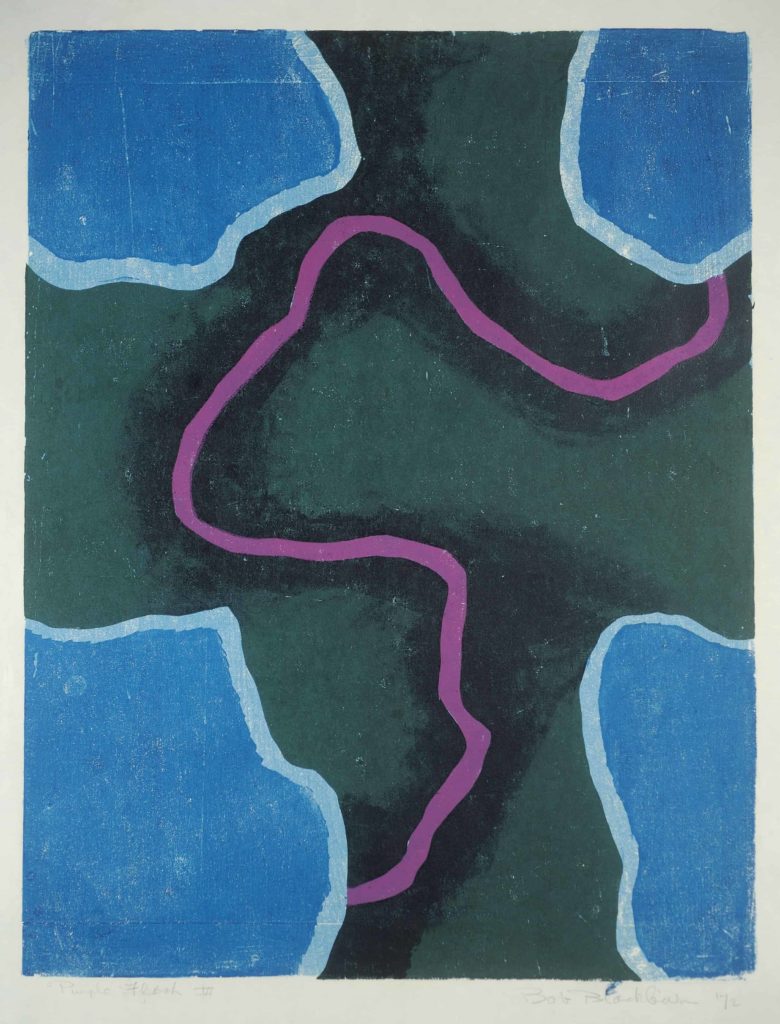

By the time he opened the print shop, he was he moving into still lifes with exaggerated or shortened surfaces, broad strokes and vivid color.

“We see him move away from representation and the sort of social commentary images he depicts in some of his earlier prints,” Canning said, “laborers, the unavailability of work, daily life. Then he moves into abstraction … color and form and space.”

Artist and Master Printer Robert Blackburn's abstract print Quiet Instrument appears in a celebration of his life and work at the Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, N.Y. Nelson / Dunks Collection. Press image courtesy of the Hyde and the David C. Driskell Center at the University of Maryland, College Park

Even when his work could seem to give less commentary on daily lived experience, he was working with artists who were very much exploring contemporary themes, Canning said: “In 1974, the workshop produces a series called Impressions of Our World, and Blackburn contributes imagery there.”

He was holding those conversations as he was pushing the boundaries and technical abilities of the print process.

“We see him growing as an artist,” Canning said. “He was a highly skilled lithographer, [and] he starts trying different print techniques.”

“Creativity … powers him through a long career and an incredible span there, from the 1930s and the Harlem Renaissance right through the Black Power Movement …”

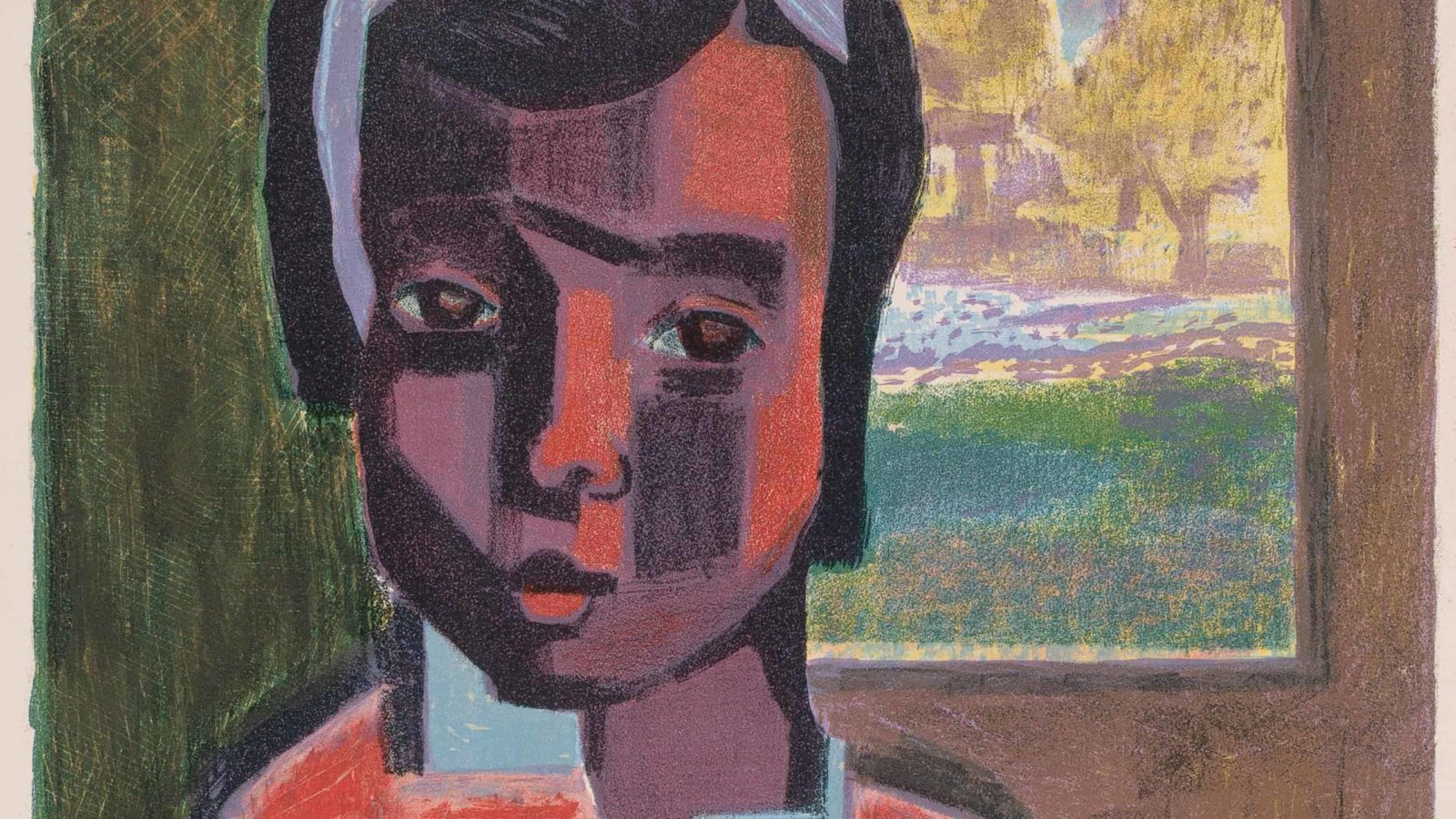

Along with generations of lithographs, the show holds his experiments in watercolors and woodcuts, viscosity intaglios, monoprints and etchings … In his 1950 print Girl in Red, a woman stands with her back to a window, looking clearly into the room. She is comfortable and confident, at the center in her own space. He invokes her in abstract broad planes of color, and the sunlight warms her forehead and her shoulder.

Founding the Workshop

In the early 1940s, Blackburn was working full-time, Canning said. It can be a challenge for an artist to have time and space resources for their work.

For a few years out of school, Blackburn held odd jobs and had no access to a press. Black artists had few grants to apply for in the 1940s, Cullen said (in a talk at El Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana organized by The Bronx Museum of the Arts — she also spoke with the Hyde on January 28 as the show opened).

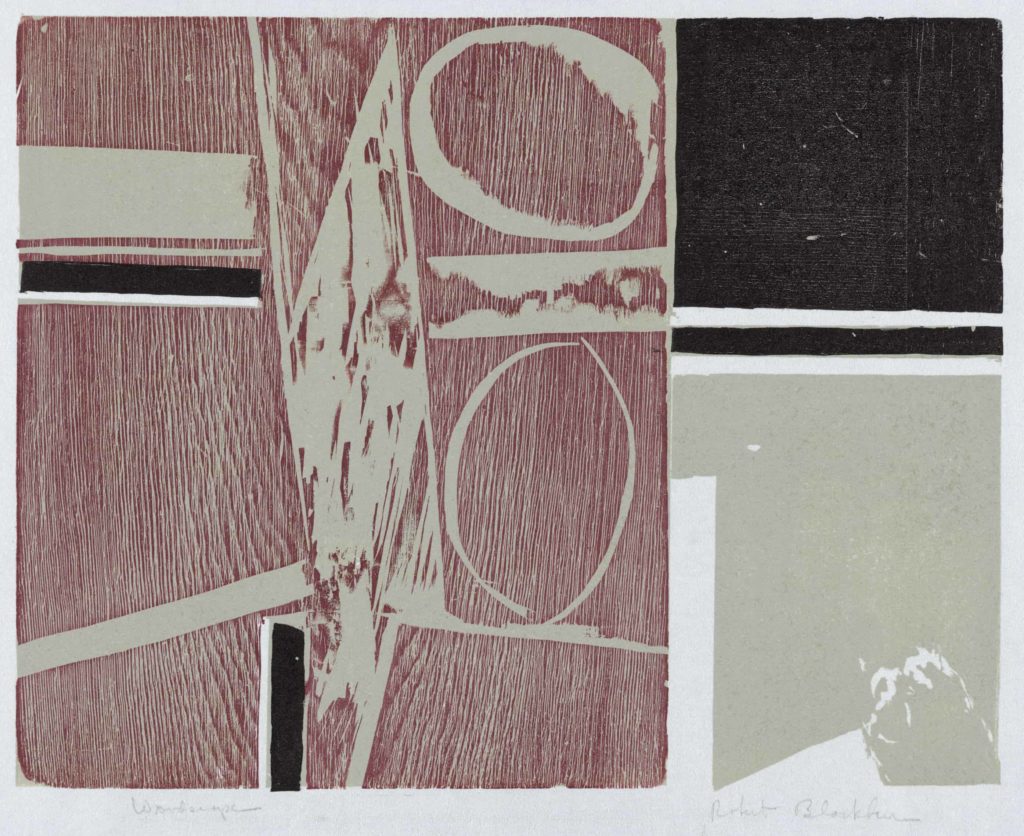

Artist and Master Printer Robert Blackburn's abstract woodcut Red Inside appears in a celebration of his life and work at the Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, N.Y. Nelson / Dunks Collection. Press image courtesy of the Hyde and the David C. Driskell Center at the University of Maryland, College Park

So Blackburn made his own way, she said. Late Oct. 1947, he got his own press and moved into a West 17th St. loft with four other artists.

“That’s the traditional artists area,” Canning said. “That’s where John Slade had his workshop and his studio in the ’20s and ’30s. And then [later] it moves to Chelsea.”

“After work he would work from 5 pm. to 2 a.m. on his own litho press,” Cullen said. “Over time, the others moved out and he kept the space.” She shared a memory from Tom Laidman, one of the founding members of the workshop who worked with Bob until Laidman died in 2010.

‘There was no elevator, and everything in the place went up on our backs, including the presses, stones, lumber for building, coal for the stove’ — artist Tom Laidman

“When I came there in 1950, the Shop was on West 17th Street in a four-story red brick building,” he recalled. “There was no elevator, and everything in the place went up on our backs, including the presses, stones, lumber for building, coal for the stove in the middle of the shop.

“We froze in the winter, roasted in the heat in summer, and the heat didn’t make the printing any easier. We went through all kinds of maneuvers to keep the images in the stones from filling in.”

Blackburn welcomed in artists, friends and friends of friends. The community grew, until it became an informal cooperative and then, in 1971, a nonprofit.

“The structure of it changes over time,” Canning said.

“The atmosphere was friendly and intimate,” Laidman said. “There was an open arrangement where … students and artists had unlimited access. There were three or four litho presses, and we’d all fight for press time. Bob was a dynamo of energy.”

Artist and Master Printer Robert Blackburn's abstract lithograph Purple Flash III appears in a celebration of his life and work at the Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, N.Y. Nelson / Dunks Collection. Press image courtesy of the Hyde and the David C. Driskell Center at the University of Maryland, College Park

Powering a community

Cullen knew that energy herself. As an intern for Blackburn, she worked with him at his workshop, and later she served as curator of the print collection at the nonprofit he helped to form, to keep the workshop alive past his own lifetime.

Not many collective spaces existed in the 1940s, Canning said. It was rare for artists to have a place like this, where they could come together. They could find the tools and inks they needed and work with printers who knew what the tools could do. They could learn and teach — and talk with each other.

“There must be so much sharing and discussion going on between artists,” Canning said. “… It becomes such an influential place for ultimately an international crew of artists to work, to share ideas and to experiment in different print techniques and media.”

Blackburn taught other artists, and he worked with artists as teachers. The Indian artist Krishna Reddy, a master printmaker and voice for abstract art in India, led workshops in viscosity — etch a metal plate at different depths and then print with inks of different thicknesses. In the 1970s, when he was creating the etching in this show, he was a professor at New York University.

‘It becomes such an influential place for ultimately an international crew of artists to work, to share ideas and to experiment in different print techniques and media.’ — Jonathan Canning, curator at the Hyde

Here he shows four boys — or are they the same boy in different times and places? — sitting on what might be sand at the tideline, in a space that feels limitless and divided into invisible rooms, with a sky like water or the grain of wood.

Blackburn made two prints in this show the same way, and he learned from many of his friends. From 1974 to 1983, Romare Bearden taught monoprinting at the workshop and worked with Blackburn on his own monotypes — together they made more than 100 prints, often on Saturdays.

Blackburn himself taught in New York and across the country. Alongside his workshop,

he served for years as professor to the printmaking workshop at the Cooper Union and taught at Columbia University and the Pratt Institute, and he held lectureships across the country, from Rutgers to UC Santa Cruz (says the catalog to Through a Master Printer: Robert Blackburn and the Printmaking Workshop, an exhibit at the Columbia Museum in 1985).

“Blackburn welcomed many Caribbean and Latino artists,” Cullen said, “and many Puerto Rican artists worked in his shop, including Nestor Otero, Juan Sánchez, Nitza Tufino …”

Cuban artists came there too, she said, including Eduardo Roca ‘Choca’ Salazar, who had earned international recognition and shown his work from Bulgaria to Galicia to the International Engraving Triennial Exhibition in Japan.

As his influence spread, over the years the artists who came through his workshop would form their own communities, and Blackburn inspired new print shops in many places. In 1978 he traveled to Asilah in Morocco to found the Asilah print workshop there.

“It’s interesting to think how international modern art was in the 1970s,” Canning said, marveling. “The idea of setting up an international print workshop in Morocco in the 1970s seems extraordinary.”

Changing ideas

From his Lower West Side workshop, Blackburn was influencing the way artists across the country were thinking about printmaking, Canning said. He became a leader and a catalyst in a national movement toward prints in the 1960s and 1970s.

For Blackburn, printing was an artform in itself tangible, messy, changeable and organic. He made lithography and many forms of printing possible, Canning said, and in introducing them to well-known artists, he made them newly legitimate. Lithography had become a technique for illustrating books. Artists more often worked with woodcuts and etching and engraving. Blackburn showed them that they could use lithography for their own ends and take it back from commercial presses and newsrooms.

Acclaimed artist Robert Rauschenberg worked with master printer Robert Blackburn to create the print Stunt Man in shades of blue. Press image courtesy of the Hyde and Universal Limited Art Editions

Many artists have turned to printmaking for freedom in the way the work is made and put out into the world, Canning said — as Japanese woodblock prints (shown at the Hyde in 2018, and showing at the Southern Vermont Arts Center and WCMA this winter) gave artists a way to show their work and gave many people a way to see it.

Artists would come to Blackburn thinking of lithography as a way to make a perfect copy of an image, a drawing or a painting, Cullen said. He knew lithography as a creative process and a way to experiment. And he shared his knowledge widely.

From 1957 to 1963, Blackburn worked as master printer for another new print shop, Universal Limited Art Editions on Long Island, and there he met some of the most widely recognized artists if the time. In those five years, he printed ULAE’s first 79 editions, including work for Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hardigan, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Larry Rivers.

Many of them had never worked in print until they met him. Blackburn had been “thinking in print’ for more than 20 years,” Cullen said. His experience influenced these artists when they began working with the stone, and he taught them what was possible.

‘He defied the idea of lithography as faithfully reproducing a rigidly identical print edition.’ — exhibit curator Deborah Cullen

“He defied the idea of lithography as faithfully reproducing a rigidly identical print edition,” she said. And he turned perspective on it’s side. An easel is a vertical surface — a press, a stone, is horizontal.

In one powerful moment, Rauschenberg and Blackburn were working together, the stone cracked — and Rauschenberg put the fragmented prints together, and made them something new.

.

“I hope this show will be a real eye-opener for us,” Canning said, “and it will open our understanding of 20th-century art.”

It is introducing him and the Hyde to many artists new to them, he said. Looking ahead to their summer exhibit on the Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada, he thinks of the Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera who inspired Blackburn as a boy, and as he sees the prints for this show for the first time, he imagines new connections they can make in the future.

“I think this show could seed a lot of future exhibitions,” he said.