In 1999, the summer Mass MoCA opened, Robert Rauschenberg came several times to see his work installed in the football-field-sized gallery in building 5. The 1/4 Mile or 2 Furlong Piece gathered images from athletes and animals to umbrellas and planets. In collage or silkscreened onto fabrics, aluminum and copper, they formed a massive record of his life, in progress for 20 years.

Lisa Dorin was a graduate students then in the art history program at Williams College, and she became the first curatorial intern in a long line to work with Mass MoCA. She caught glimpses of Rauschenberg, she says, as he explored the new galleries in the old mill.

This summer, Mass MoCA has opened its new building 6 and doubled the size of its campus, with Rauschenberg’s artwork front and center — and Dorin is the deputy director of curatorial affairs at the Williams College Museum of Art, just up the road, and co-curator of “Autobiography,” a retrospective show there digging into Rauschenberg’s newly opened archives.

Museums in the Northern Berkshires are working together, formally and informally, and in summer 2017 the organic exchange behind the scenes has become more visible.

With the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown and the Bennington Museum in Bennington, Vt., Mass MoCA and WCMA have launched Art Country, a new initiative to show the depth of visual art in the Berkshires and Southern Vermont.

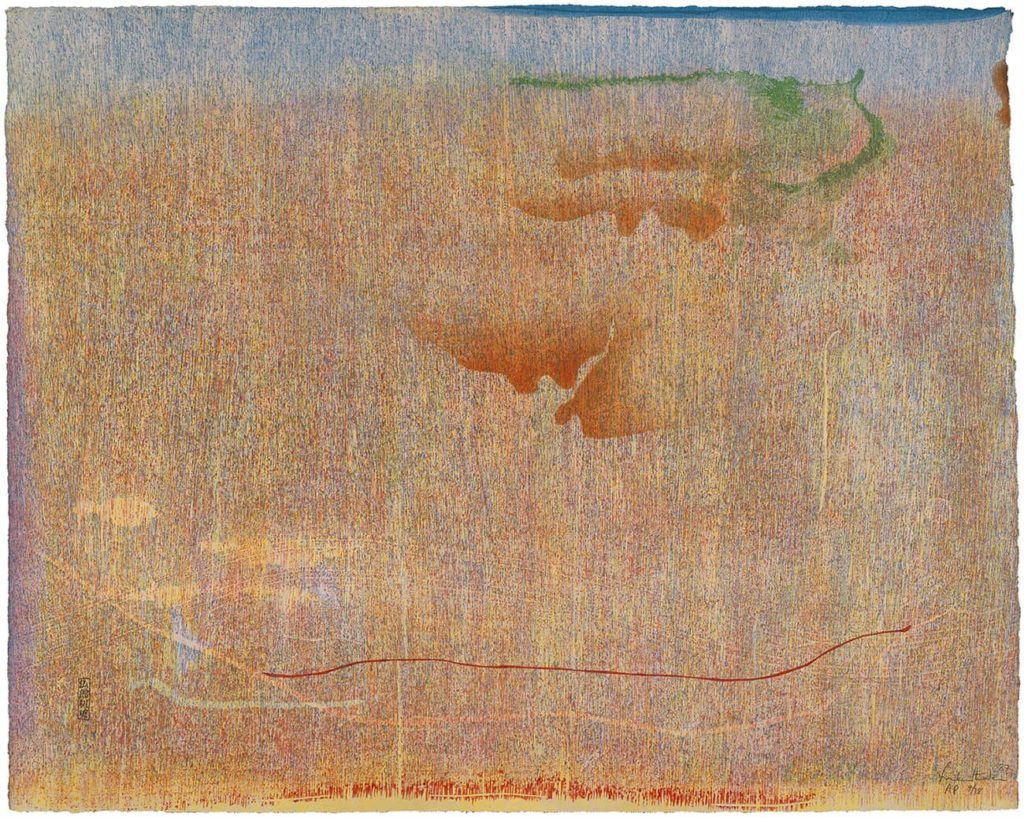

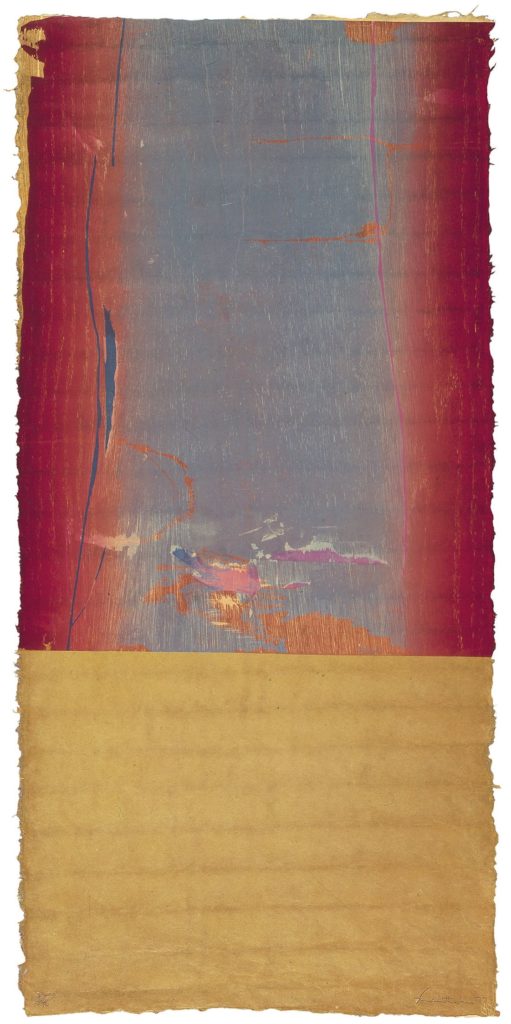

That depth surfaces naturally in ties between this summer’s shows: Rauschenberg, at WCMA and Mass MoCA, was leading and outrunning every art movement in his lifetime, and his work has inspired contemporary artists in both museums who have come through the Rauschenberg Foundation’s artists’ residency program at Captiva, Fla. And the Clark Art Institute and at the Bennington Museum look at Helen Frankenthaler, an artist working at the boundaries of her field from the 1950s to the 1990s.

Frankenthaler will hold the spotlight in two shows at the Stone Hill Center at the Clark — As in Nature, a look at her paintings across 40 years, and No Rules, focusing on her woodcuts — and she will appear in the central summer exhibit in Bennington.

The artist Morris Louis called Frankenthaler’s Mountains and the Sea “a bridge from Pollock to what is possible,” says Bennington Museum curator Jamie Franklin. She found a way forward from Pollock’s splatters of paint on canvas, executive director Robert Wolterstorff explains, staining her canvasses and soaking swathes of intense color into them, often without line or composition.

Her work often walked the line between representation and abstraction, as in Abstract Landscape, a work overlaying mountain ridges with bright shapes, says Alexandra Schwartz, curator of As in Nature.

Frankenthaler was painting the Green Mountains while another artist, coming into international fame, painted them from the far side of the ridge. Franklin and Wolterstorff will bring Frankenthaler into a show that will set Grandma Moses in the context of the art world when she was painting — the art world that received her into it. Moses’ first show outside Hoosick Falls, N.Y., was at the MOMA, Franklin says. And her work has more ties to Frankenthaler’s than may appear at a glance.

“Helen Frankenthaler’s Mountains and Seas is a memory painting of a landscape,” he says, as Moses’ paintings were memory paintings and collages. “It’s Nova Scotia, waves pounding on the shore.”

In this show, they will show Silver Coast from her honeymoon on the coast of Portugal.

In planning their own summer, WCMA has turned to one of Frankenthaler’s agile contemporaries. As Frankenthaler explored new etechniques in the woodcuts in No Rules, writing that artists should “go against the rules or ignore the rules — that is what invention is about,” Rauschenberg was ignoring and rewriting the rules in his own way.

He was known for mechanical imagery, expressionistic brushstrokes, and blending sculpture with painting, says Susan Cross, curator at MASS MoCA — and for moving ahead of his time: “He was so current, so prescient, he feels so new, and he was doing it in the 60s.”

WCMA has planned “Autobiography” knowing that MASS MoCA would also honor Rauschenberg, Dorin says. She and Williams art professor C. Ondine Chavoya, and a fall art history class, dove into the newly opened archive of Rauschenberg’s papers and paired their findings with artworks across the decades, from photographic prints made directly from his body to footage of dances he choreographed.

At MASS MoCA, Rauschenberg’s A Quake in Paradise (Labyrinth) will sit at the entrance to the new Building 6 — a maze the artist designed in images on clear panels.

“It’s a print work, but a sculpture you have to move your body through,” said Larry Smallwood, deputy director of MASS MoCA.

It will accompany The Lurid Attack of the Monsters from the Postal News Aug 1875, a 1981 sculpture incorporating antique saws. And MASS MoCA will keep up the momentum with work by artists Rauschenberg has inspired, including Lonnie Holley and Dawn Dedeaux’s collaborative work with found objects, some from Captiva that belonged to Rauschenberg himself. While at WCMA, Meleko Mokgosi, Williams College ’07, includes prints he has made at Captiva using Rauschenberg’s techniques.

Rauschenberg would have enjoyed seeing his work here and the connections it has made, Smallwood says: “I think he’d get a real kick out of all of this. He seemed to have a great time here.”

Frankenthaler also has roots in the mountains. She graduated from Bennington College in 1949, and in 1979 she returned as an artist in residence at Williams College, says Jay Clarke, curator of prints, drawings and photographs at the Clark and curator of No Rules. In 1979 the Clark held a show of Frankenthaler’s prints.

So the new partnership between the four museums has grown out of a shared history among them and two colleges.

“The unspoken coincidence is that we all trained here,” Franklin says.

Robert and Dorin and he are all Williams art history graduate students, and Mass MoCA’s director, Joe Thompson, is a Williams College alum.

That experience can give deep ties to this place. When Franklin first came here for graduate school, he drove across the country with his family in one car, and he remembers vividly seeing the sun setting in Pownal Valley.

“In 1950s, it was touted as one of the most beautiful places on earth,” he says, when Frankenthaler and Moses knew it.

He thinks it still is.

The story above first ran in the June 2017 Berkshire Magazine; my thanks to Anastasia Stanmeyer.