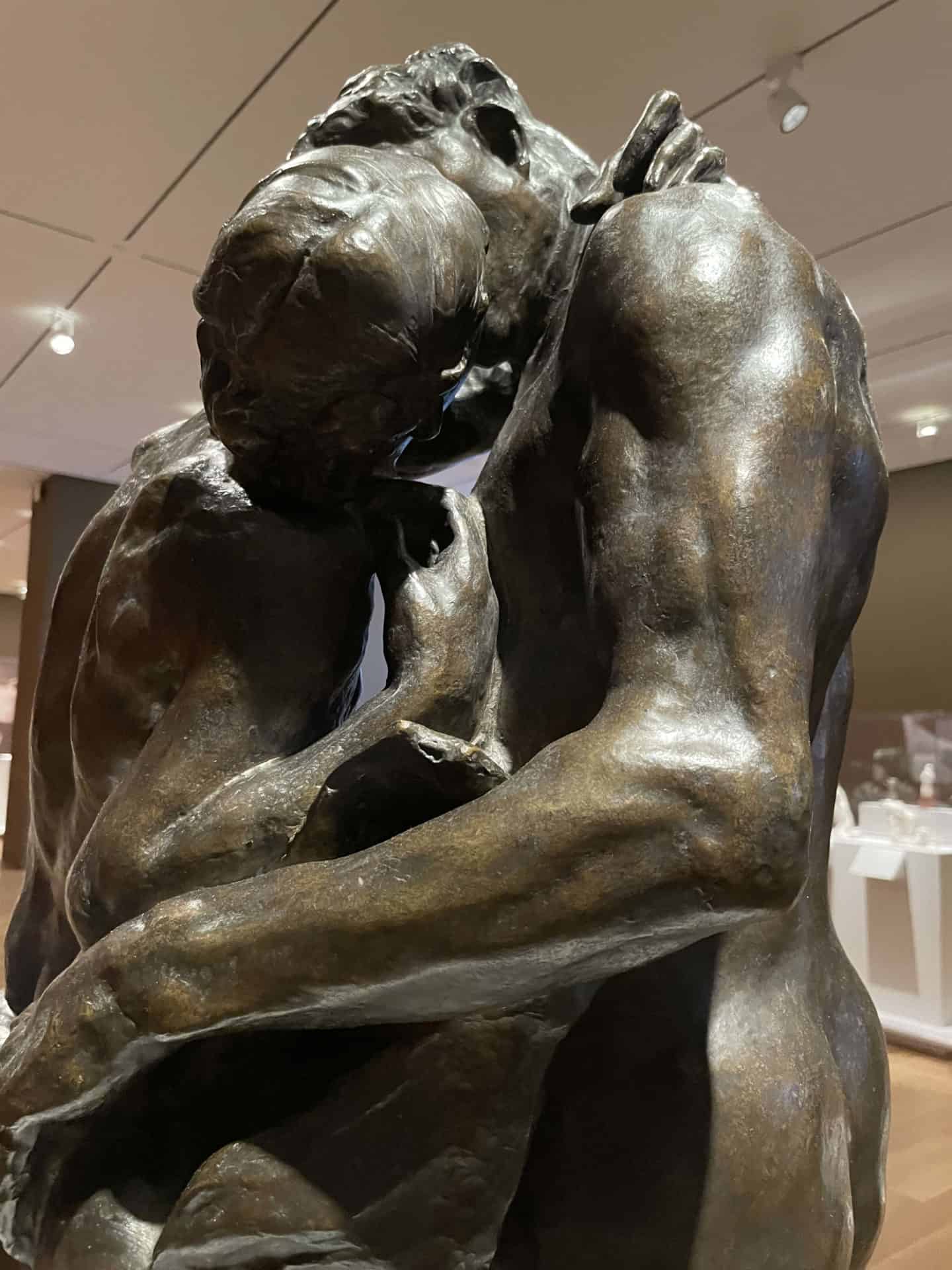

The two of them hold each other skin to skin. Her hands open on his shoulders, close and familiar, and their bodies blend together in smooth stone. Psyche and Eros lie together on a summer morning, clear to view at the opening of the Clark Art Institute’s largest summer show.

They are the first of Auguste Rodin’s sculptures ever to come to America. And when they first came here in 1893, they were put away in the dark.

Bronze lovers embrace in Rodin's 'The Kiss' in 'Rodin in the United States' at the Clark Art Institute. Photo taken with permission from the museum

“They were sensual, and also natural,” says Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, curator of this exhibit of more than 75 sculptures and drawings. “Too strong a feeling of nature disturbed the Americans.”

‘They were sensual, and also natural. Too strong a feeling of nature disturbed the Americans.’ — Antoinette Le Normand-Romain

In Rodin in the United States: Confronting the Modern, she is considering how America saw the artist and his artwork for more than 100 years.

She knows him well, from long contact — Le Normand-Romain is exhibition curator and former director general of the National Institute of the History of Art in Paris, and before that she served for 12 years as the former curator of sculpture at the Musée Rodin, just across the river from the Louvre.

In her writing and curation, in books and essays and exhibition catalogs, she has presented Rodin as the first Modern sculptor, one of the earliest Modernist minds in the world. Here she follows his work across the Atlantic.

Walking through the show, as she guides the press tour, she makes clear how often women brought them here. And they are creative, intelligent, forceful women, making careers of their own work in their own right — a sculptor, a dancer and choreographer known around the world, a journalist, Agnes Ernst Mayer, who studied at the Sorbonne, wrote for the New York Sun, published an art magazine with Alfred Steiglitz, fought for Civil Rights and public education and married the editor of the Washington Post …

Psyche and Eros came to Chicago in the hands of an art curator — Sarah Tyson Hallowell — Le Normand-Romain says, as she pauses beside two bronzes, Assemblage of a Watchman and A Seated Bather, each small enough to hold in two hands. Hallowell brought three of Rodin’s marble sculptures to an exhibition that drew more than 27 million people.

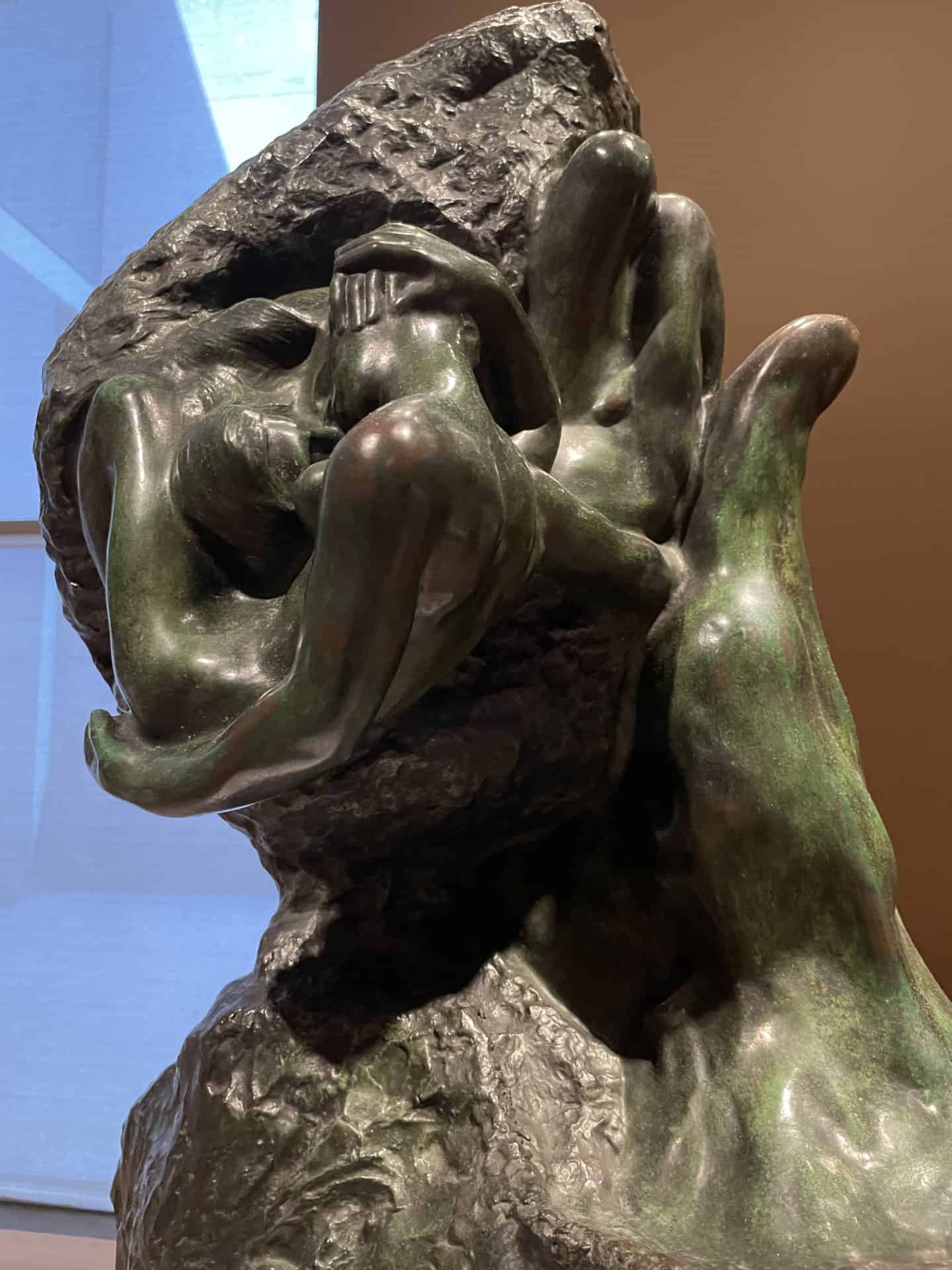

A bronze palm cups two human figures in Rodin's Hand of God.

That quick sentence begs a hundred questions. Who was Hallowell — and how did a woman hold a role in curating a show that brought in as many people as a third of the population of the whole country at the time — a generation after the Civil War, when women had almost no foothold in the art world in America or in Europe?

The Clark’s own recent show of women artists in Paris in the 1890s shows how rare her influence was. Hallowell was a Quaker woman from Philadelphia, probing out past the leading edge of the art world on two continents, 50 years before women affirmed the right to vote.

In the 1870s, in her 20s, she had already made a career as an agent and curator between Europe and America, working with some of the most widely known artists of the day, in both continents, from James McNeill Whistler to John Singer Sargent. In 1878 she organized the Inter-State Industrial Exposition of Chicago.

By 1890 she was near the height of her career, bringing Degas, Monet, Pissarro, Alfred Sisley and Pierre-Auguste Renoir to her home city. She served as assistant chief of the exhibition. And she went on to become the Paris agent for the Art Institute of Chicago.

So she would have come to Rodin’s house and to his studio. She knew him and his circle. She could well have known Camille Claudel — his student and colleague, fellow sculptor and artist in his atelier and then in her own. Hallowell could have talked with her while she was at work with clay … and seen Loie Fuller dance under the new charged medium of colored electric light.

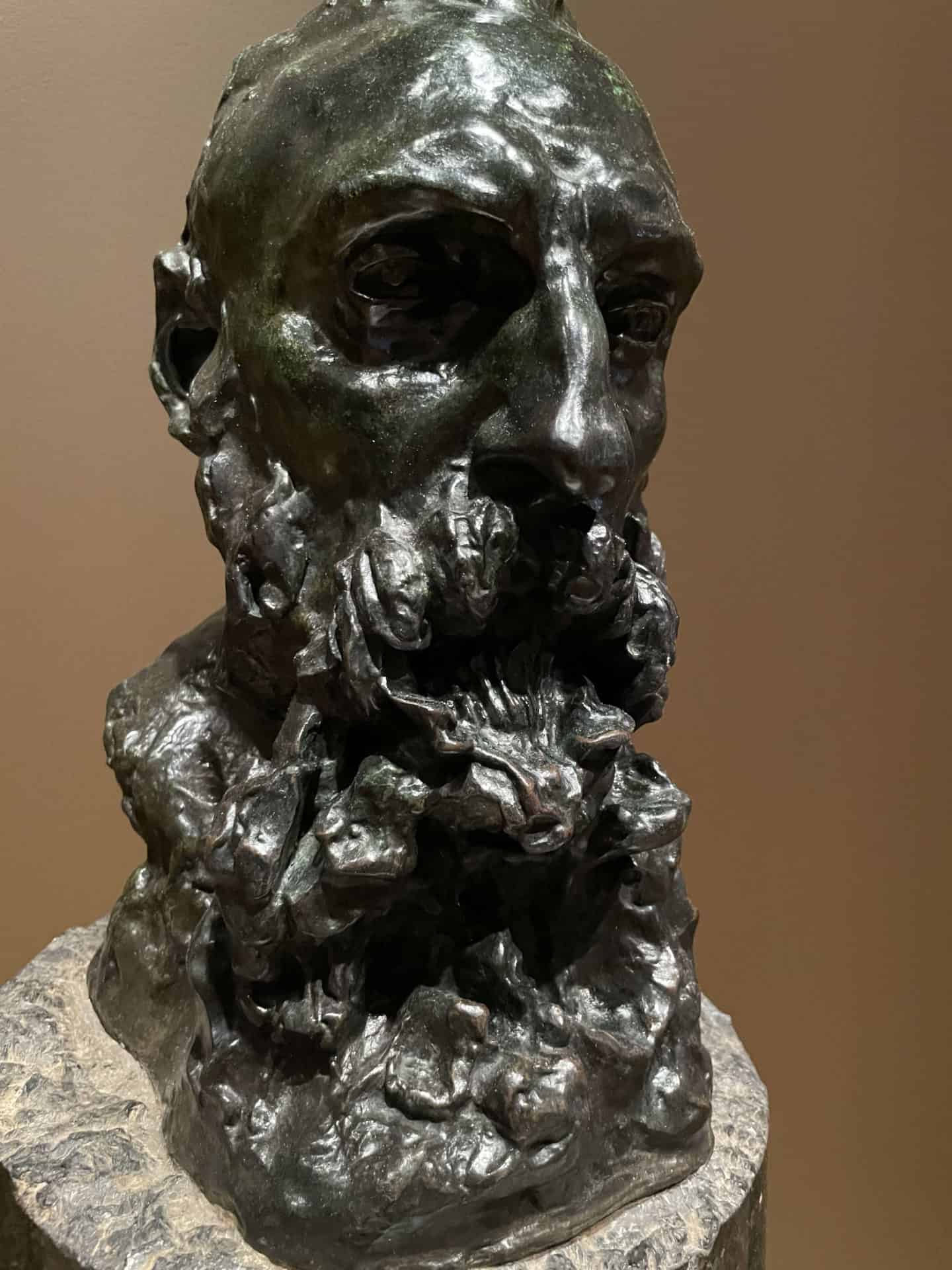

Standing eye to eye with Claudel’s bronze bust of Rodin, Normand-Romain fields a question about Rodin and Claudel’s relationship. She says Claudel was a student of Rodin’s like any other, and she moves away and closes the conversation.

But she has also written a book about Claudel and Rodin and curated an exhibit bringing their work together.

For some 20 years, Claudel earned national recognition as an artist in her own right. She exhibited this bronze of Rodin at the 1892 Salon in Paris, and the panel beside it explains that she has her own museum now, a building in clear lines of artisanal clay brick in the old town center of Nogent-sur-Seine, in her childhood hometown.

Camille Claudel — a life realigned

At the Clark this summer, in the reading room the museum has created upstairs beside Rodin’s colossal figure of Honoré de Balzac, and there Camille Claudel — A Life by Odile Ayral-Clause gives a glimpse of the Paris where Claudel and Rodin both lived.

Claudel was 17 when she first came here to the city full of art schools and shared studios and artists from across Europe and America. She was studying at the Academie Colarossi and leading a group of artists and friends their own atelier (studio) in Notre Dame des Champs. She had a sculpture of her own accepted to the Societé des Artistes Français in 1883, when she was 19.

Sculptor Camille Claudel reveals Rodin in bronze at the Clark Art Institute.

‘… some elegant and svelte, the others knotty and tense … gnarled, furrowed … deep and dramatic.’ — Matthias Morhardt on Camille Claudel’s work

Ayral-Clause opens with a strong sense of Claudel’s creative energy and scope. Rodin calls her a woman of genius in his letters, and Claudel’s first biographer, the journalist Matthias Morhardt, presents her as Rodin’s equal.

Even in her first months as a student in his atelier, Ayral-Clause writes, Claudel modeled the hands and feet of many of the figures in some of Rodin’s major works, the Burghers of Calais and the Gates of Hell — the elements of any figure that he held pre-eminent.

Morhardt knew Claudel and Rodin, even in their earliest years working together. He describes her at work, absorbed in the feel of clay and the shape of muscle and bone in an ankle or a palm.

“To this day we could still find at Rue de l’Universite several of those hands, some elegant and svelte, the others knotty and tense …,” he wrote. “(Rodin) consults with her about everything. He deliberates each decision with her, and it is only after they are in agreement that he proceeds.”

She became a praticien, one of the rare sculptors who could carve marble — Rodin himself did not. And Morhardt saw a strength in her work distinct from Rodin’s, in her contrasts of light and dark, “gnarled, furrowed … deep and dramatic …”

“They did not look like Rodin’s art,” he writes, “any more than Michaelangelo’s art resembled Donatello.”

Claudel seems to have been conservative in some ways and radical in others. In 1893, when Eros and Psyche were closed in a Chicago back room, she was encountering opposition over her bronze of la Valse, a man and woman who dance close together, turning with the momentum of the movement, and almost naked.

The woman’s flowing draperie might raise a question … whether Claudel knew the woman whose name appears a few feet away, at the entrance to the room. She could easily have seen her perform. Most of Paris was watching.

Rodin's sculpture shows Camille Claudel encased to the chin in marble.

That same winter, in 1893, Loie Fuller was becoming a craze in France. She would dance with light and shadow, “her figure now revealed, now concealed (said the New York Spirit of the Times) in a white silk robe, and bathed in a new invention — colored stage light.

In Paris, her dancing and choreography were transforming the Folie-Bergère, drawing sold out crowds night after night.

She appears here too. In 1903, fast becoming one of the most famous dancers in the world, she brought Rodin’s work to New York in a show of art from her own collection.

“Fuller has a great admiration for Rodin and has more plaster and bronze than have ever been shown at one time in this country,” the New York Tribune wrote in anticipation.

Fuller’s show did not succeed, Le Normand-Romain says, though she does not go into detail. Rodin was angry at the time, she says, but he also held Fuller in respect high enough to dedicate a bronze cast of the Thinker to her.

Responses at the time suggest that the city responded to his work in many ways, loudly and viscerally, with anything but calm. The New York Times said as her show opened, May 9, 1903 — “Rodin himself is the sculptor most discussed, most condemned, most admired and copied at the present day.”

‘(Rodin’s work) seizes one along despite all protests; it excites and disquiets … but it makes one think and in the end compels one … to acknowledge it’s power.’ — New York Times, 1903

The writer here (unnamed in a review without a byline) also veers between condemnation and admiration, caught up in response to these bronze people and the feeling in them — Rodin’s work “seizes one along despite all protests; it excites and disquiets … but it makes one think and in the end compels one … to acknowledge it’s power.”

The story gives some sense of an educated American at the turn of the 20th century confronting Rodin’s sculptures for the first time, and feeling shaken. Dante looked back in this show too — in the Thinker, a beautiful nude man of mature age and a rich patina. And the poet Victor Hugo, powerful, pensive and equally bare, sat “on the rocks of Jersey like a Nocterne.”

Out in the channel islands, that bronze man holds the strength and form of the rocks at night and the incoming tide.