Young artists are painting in broad strokes. They are standing around a table spread with a long roll of paper, and together they’re making a pattern of vines and leaves and flower petals shading from rose to cream. The flowers are open as large as the palm of a child’s hand.

The painting began with a walk in the woods. Earlier in the day, the group went for a walk together and brought back whatever caught their eye, a leaf or a pine cone or an acorn. Then they picked one to draw until the shape began to feel abstract and new.

Just off Main Street in North Bennington, Patricia Pedreira has re-imagined the Sage Street Mill as an “arts and wellness generator,” with Saturday art studio conversations, art exhibits, an after school arts club for students and digital studio for entrepreneurs.

The Sage Street Mill holds a day camp in arts and wellness with a wall of things campers feel thankful for.

From December 27 to 31, they will expand their newest program for kids, a Winter Wellness day camp, said Ahmad Yassir, manager of Sage Street Mill Initiatives, Programs and Partnerships. He is an artist and teacher and a Bennington College alum, and he has lived in North Bennington now for five years. He grew up in Lebanon, he said, and studied in Bosnia Herzegovina, and he has lived and taught in many places, in Lebanon and Turkey and Somaliland.

Here he guides his students in an art studio with tables and paints, wood and clay and scraps of cloth, full of found objects and color. It opens into a sunny open room where the group can gather for morning circles and meditation, and outdoors they can explore a creek and paths through the woods, and a lake close enough to walk to.

“It is so important for kids to have a safe place to connect and socialize, make art and explore nature,” Pedreira said by email, both inside our beautiful art studios at the Sage Street Mill and outside in nature.”

She is an art therapist and an artist, Yassir said, and their education programming has taken root from her ideas. He has observed with her and has grown their camps and workshops, as he has grown his own artistic practice. at the mill, they want to create a sense of trust, he said, and a balance of indoor and outdoor explorations, arts and yoga, and structured and flexible time.

They want to create a sense of trust, he said, and a balance of indoor and outdoor explorations, arts and yoga …

In the summer, he led a wellness camp with a group of kids anywhere from 6 to 12 years old. He tries to get to know each camper and to see them grow, he said, even in a week or two. He wants to be open to their interests and excitements, and it has been invigorating and fun for him too, to teach in person again after a year and a half of not being able to come into a classroom together.

Each day they open with a morning circle, he said. He will have ideas and possibilities, and he will invite them to help plan the day. The whole group may sit quietly in the yoga studio for a meditation or stretch themselves with sound games and animal games. They will have time in the art studio and on the trails, and they will come back into circles through the day to reflect on conversations with each other or talk about minor tensions and untangle them.

“We are a unique kids camp and place, Pedreira said. “Here we offer creative opportunities for kids to learn and express themselves through the arts, along with … wellness practices such as mindfulness, daily arts and gratitude journaling and teamwork, all while having fun.”

In the arts studio, the campers have the freedom to play with their own ideas, Yassir said. He will often give them a prompt, and then they can choose a medium to work with. They may spend the morning painting on wood or making sculpture from blocks. They may imagine an island or a town. They may walk the trails on the mil’s five acres and up the path to Lake Paran and gather natural elements to bring back.

“We want the kids to be open,” he said. “Kids are used to drawing on paper, over and over, so we work with found objects.”

Sunflowers bloom outside the Sage Street Mill in North Bennington.

He gives his students time to make plans, and to start a project one day and come back to it the next. They each have a journal for writing and drawing and jotting down ideas, he said. He remembers one young artist making a sketch on paper. He saw her painting the same image on wood, copying her sketch exactly, and he asked her whether she could find anything in the studio to bring her new inspiration. And she began to add to her painting, drawing in new colors, purple grasses and sunset clouds.

He wants to give all of his students room to follow their curiosity, he said: “If we go on a hike and we stop to look at a tree or a leaf or a bird, not everyone will be interested.”

He also encourages them to look closely. He and his students have created projects inspired by Andy Goldsworthy, the internationally known artist who will create sculptures out of snow or leaves or stones, moving them to make shapes and forms and photographing the work, and then leaving them to resettle over time. He’s changing the landscape lightly.

Yassir and his students talk before they head outdoors, he said. He will not expect them all to stay in a neat line on the trail, he said. They talk together about how they all want to be when they are outside, so they will pay attention and take care.

“Especially when you see kids who want to take a stick and hit a tree,” he said, “there’s a lot of aggressive behavior toward nature. Goldsworthy’s called an earth artist. He’s not invading, not destroying anything for his own profit, but he’s creating a pattern.”

Yassir and his students talk about what it means to them, that they live in a place with protected forests and lakes and rivers. In winter he plans to walk with them on the trails in the snow and play games in the fields.

‘We want the kids to be open. Kids are used to drawing on paper … so we work with found objects.’ — Ahmad Yassir

They will also create projects together. He wants them to be open to the idea that art can be collaborative, he said. Not many Western artists seem to work in collaboration, he said. So he give his students them examples.

They may join in a quiet activity like drawing circles in different colors. Together they have explored solar panels and green energy, or maps of the town and the lake. And then they range farther. He shows them works from artists from the area, and artists from many places around the world. He has brought them photographs from places where he has lived. The images sometimes surprise them, he said. He shows them Lebanon, and they see green wooded hills.

One morning he brought them traditional cloth from Somaliland to see and a book about fiber art around the world, from blue and white dyed batiks to South American weaving and Persian rugs. Then the group designed their own woven carpet and drew it full-size on a long sheet of paper, with a tiger looking out at the center.

He and his students talked about the difference between making something by hand and manufacturing by machine, he says. Arabic has a word for that kind of individuality — abrash means the unique irregularities that come from an artist or maker, when each work they make is different.

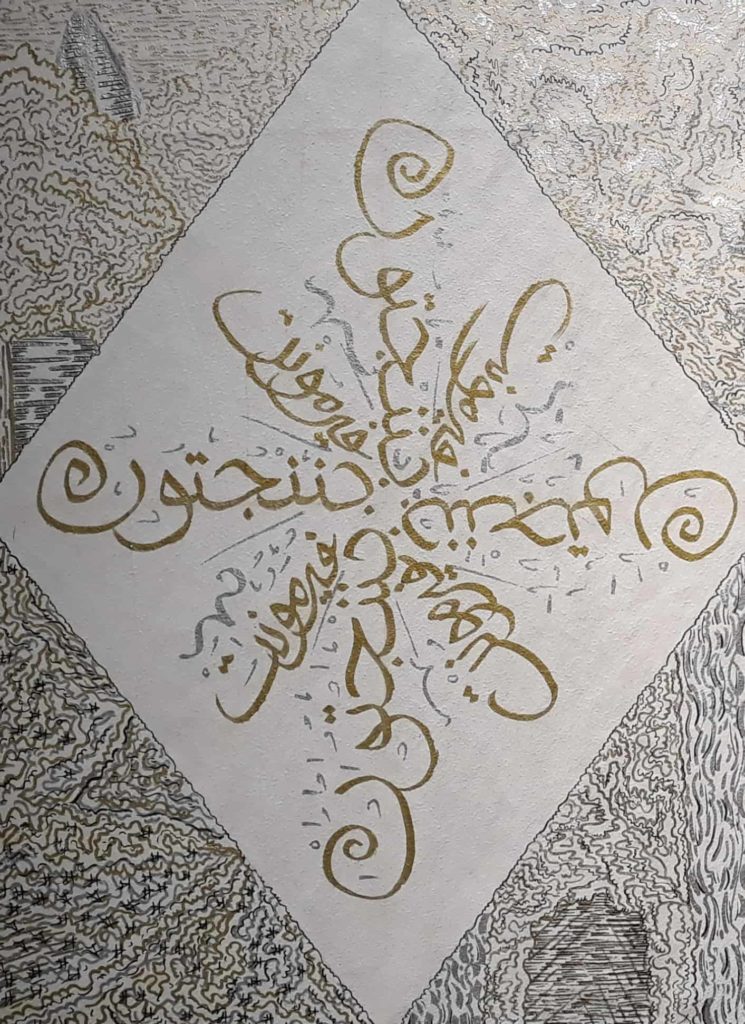

North Bennington artist Ahmad Yassir blends calligraphy, geometry and individual expression in 'Local Abrash.' Press image courtesy of Bennington Museum

“Lead instructor artist Ahmad Yassir brings amazing teaching skills and experience to the Camps,” Pedreira said. “Kids love to learn from Ahmad, especially drawing, printmaking, building and painting… He provides fun opportunities for kids to work on their own individual art projects as well as team projects.”

So Yassir gives his students ideas as varied as the explorations in his own sketchbooks

He has shown them his notebooks and talked with them about his art practice, he said.

As he turns the pages, he explains what has caught his eye.

Here he is sketching trees that follow the grain of the wood or the patterns in the bark. He draws the movements of a dancer or the shadows of the spokes of an umbrella. He highlights architectural details, real and imagined, and takes notes on similarities between Quaker and Islamic art. He draws with organic dyes like beet juice and looks for shapes in natural forms, a ridge line or a mushroom. And he evolves his own symbols.

For his students, he said, working on art projects, on their own or as a group, gives them time to talk together, and it can give kids of different ages a good way to connect. They will have time in the studio, and then they will gather for snacks and lunchtime.

“This might be something I’m bringing from my own culture,” he said. “It’s important for me that we eat together, and it helps to set a rhythm … It brings conversations.”

The kids talk about what they’re thinking about and what they want to do, he said.

Sometimes they will talk about what they are feeling, or something they are going through.

“This past summer,” he said, “some kids I got to know enough enough, even in a week or two, that when they had an odd feeling, they would let me know. They would get used to approaching me.”

They would trust that he would listen and be open.

He feels the importance of making connections and sharing perspectives. For many of his students, he said, it may be the first time they have had a teacher of color, or the first time they have met someone from the Middle East. And as they talk with him, they get to know him, and they realize they share background with him. He lives here, and he is a Bennington College alum.

He explores many of those thoughts in his own artwork, he said, themes of connection and understanding, individual expression, culture and history. He wants his works to invite questions.

“I want them to be open to conversation,” he said.

He has work on display now, just up the road in the Bennington Museum’s Transient Beauty winter show.

In a diamond pattern like the one his students have drawn for their rug, he writes in calligraphy, flowing script in gold. He has not given the translation there, he said, because he would rather have people ask him. He would rather have them think and wonder, and ask questions. And if they ask, he will gladly share the stories in the work that bring together Arabic script and Vermont.

He has surrounded the words in geometric patterns like snowflakes and the stars of Arabic tiles, and trees like the balsam firs on the ridges and the cedars he grew up with in on the Mediterranean.