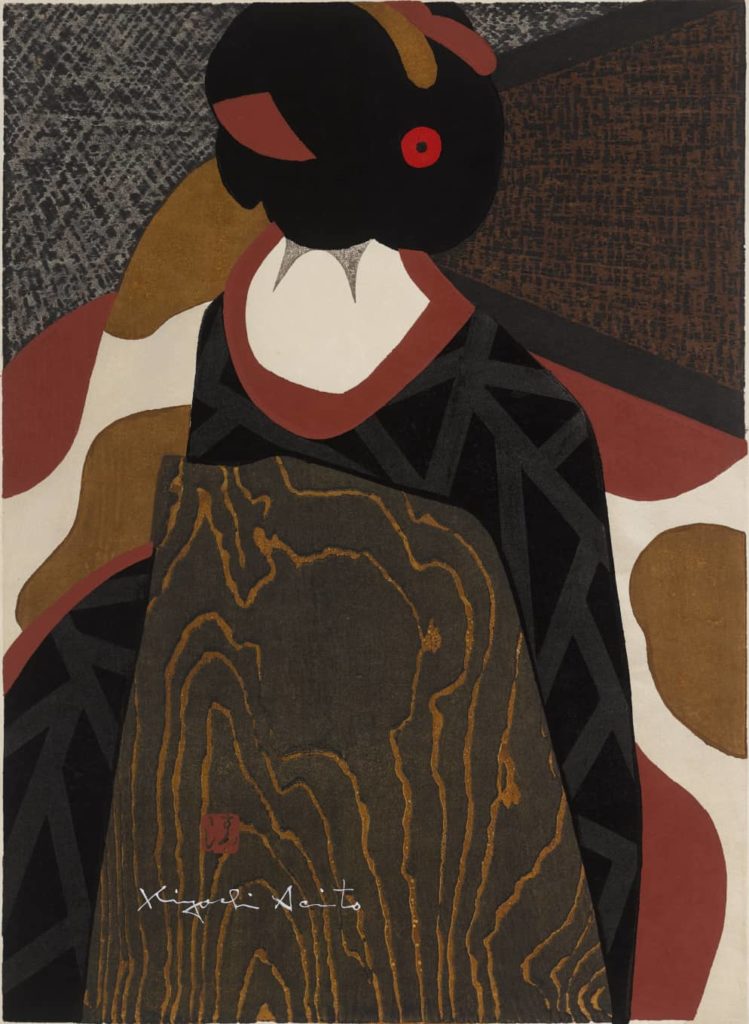

Saito Kiyoshi is walking through a street lined with machiya, tall, lean wooden houses. Afternoon light slants down an alley-way, and he can see someone in silhouette walking from the shadow into the sun.

I’m looking at his woodblock print, Gion in Kyoto (1959), in Competing Currents, the newest show at the Clark Art Institute, and I’m wondering about him.

Gion is an old and well-known Geisha neighborhood in Kyoto. When I look for it, I find tea houses and restaurants serving kaiseki, light courses in a river of small bright dishes. The Kenninji temple around the corner has a garden of stone raked as smooth as new snow.

Saito Kiyoshi's print Gion in Kyoto shows a figure walking from light into shadow in a passage from a city street, in bold and earthy colors. Press photo courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

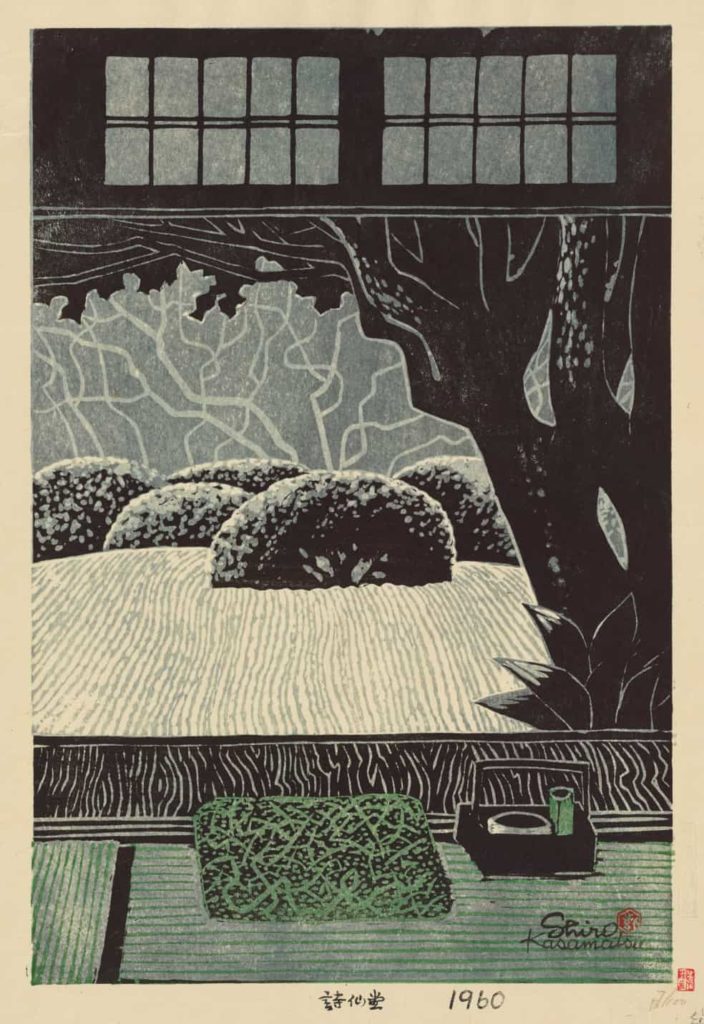

I imagine Saito standing there in the courtyard, feeling the fine gravel settle under his feet and thinking of winter days. And then he’s sitting at home in whatever corner he has set up for his wood blocks and his inks. They are both expensive, and he makes do with cutting different parts of this scene into block and coloring them in a few bold shades.

You need a virtuosity and agility with cutting tools to make a print like this, says Anne Leonard, Manton curator of prints, drawings, and photographs at the Clark. She points to lines as fine as the stroke of a pen, distant figures and effects of shadow.

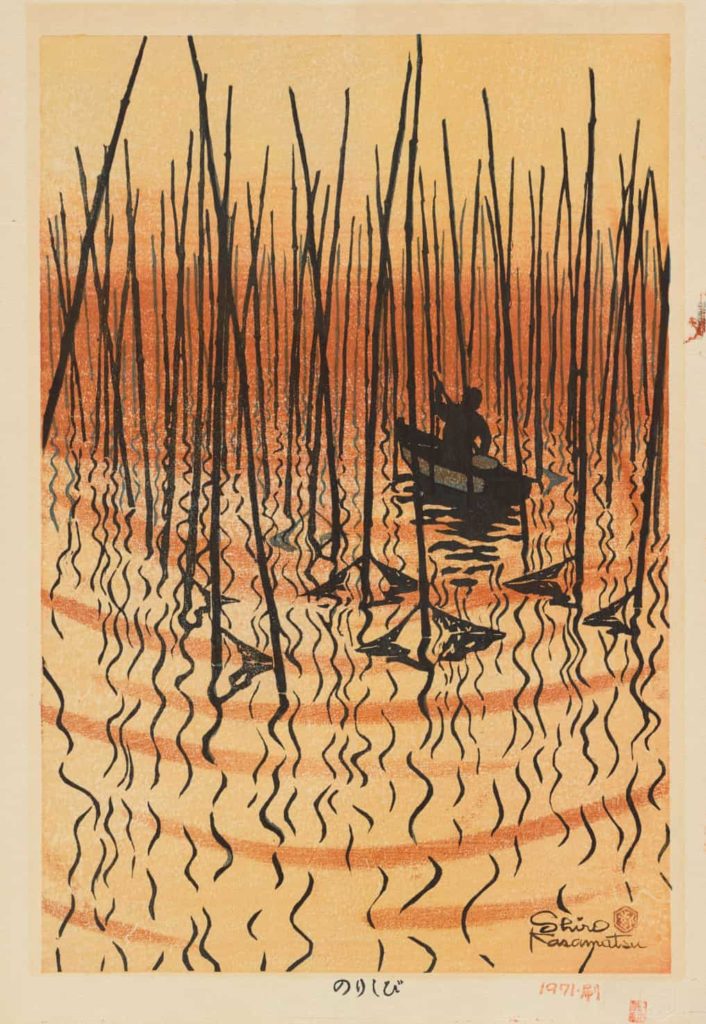

The carver would pare away the wood to leave only the surfaces to hold the ink, she says, and then print one color at a time in overlapping layers. Saito and his fellows would play with the texture and and surface of the wood. The ripple of the grain could become folds of silk in a woman’s obi (her wide sash bound around a kimono) or the furrows of light snow over meadow grass.

Saito was an artist in Sōsaku-hanga, creative prints, a movement that transformed a Japanese artform that had existed for centuries. He was a coal miner’s son from the north, and he taught himself and then studied in Tokyo. As a young man he painted in scraps of time after work. And then he discovered printmaking, and it transformed him, too. Between 1938 and his death in 1997, he exhibited and traveled around the world.

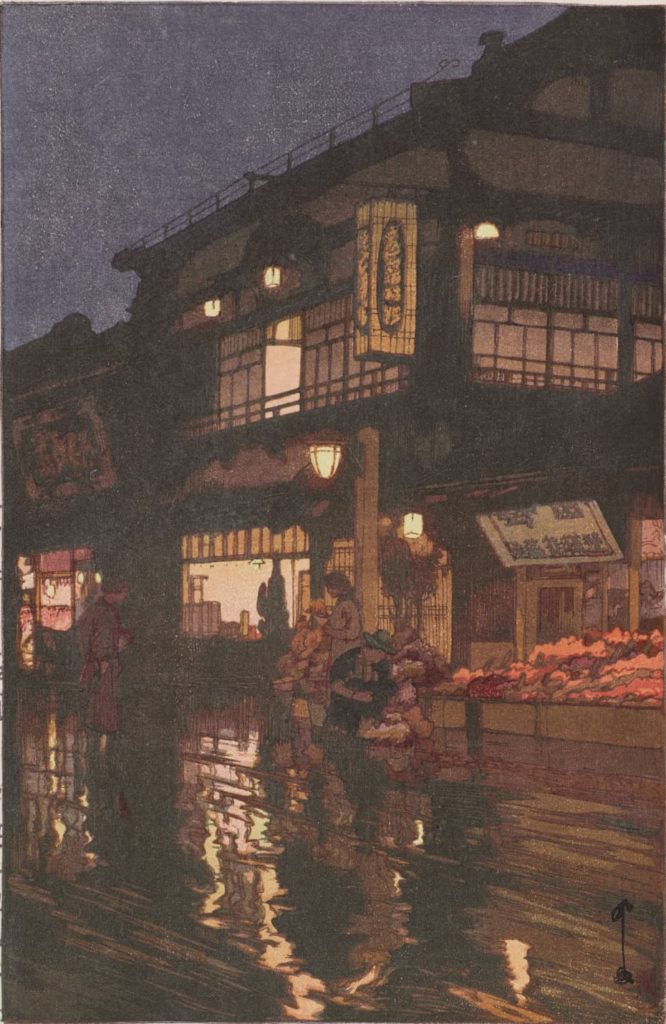

In the Clark’s library I find him in Paris, and then in India, catching cityscapes at night.

The tower of a minaret shows in the distance, and women are walking past wrapped in cloth that seems to gleam with dancing light, as though it’s woven with luminescence and glow sticks.

Sōsaku-hanga artists changed the artform because they would carve their own blocks, apply their own inks and show their own works, Leonard says. Earlier on, artists would work with woodcarvers and printers, even in Shin-hanga, the revival that carried wood block printing into the 20th century.

A fill moon rises over the water in Tsuchiya Koitsu's print, Suma Beach. Press image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

But how do the artists work, either way?

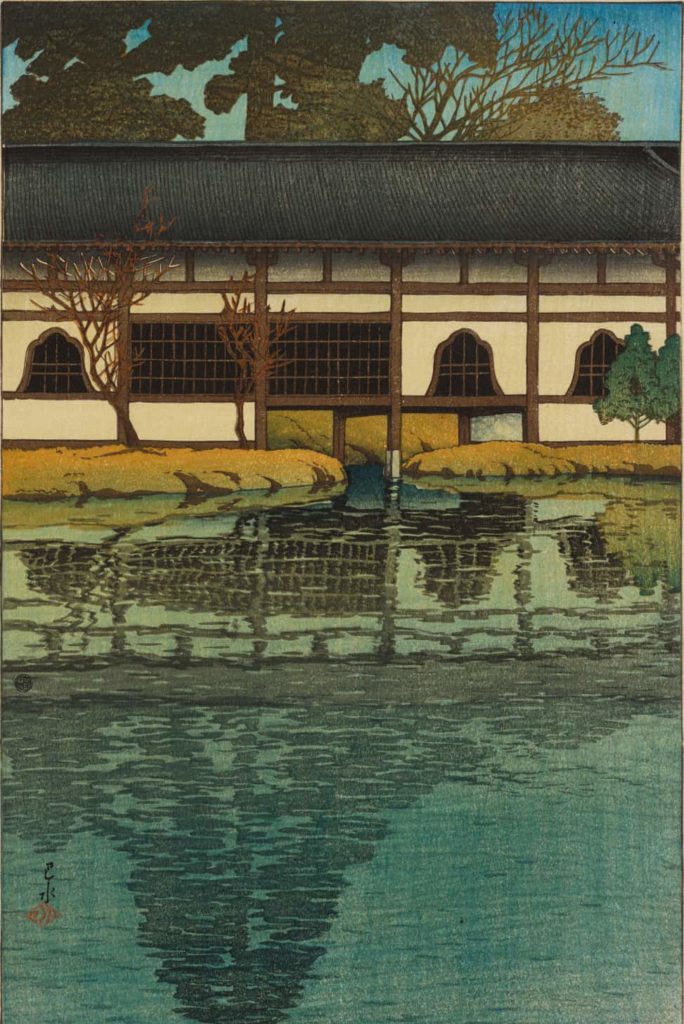

Leonard walks through the show with me and looks closely at the shifting shades of blue in a river as the water deepens or catches the shadow of a bridge. She points out a person standing by the rail, small but clear in a blue coat, and the precision it takes to show the lighter wood of the railing as they lean against it.

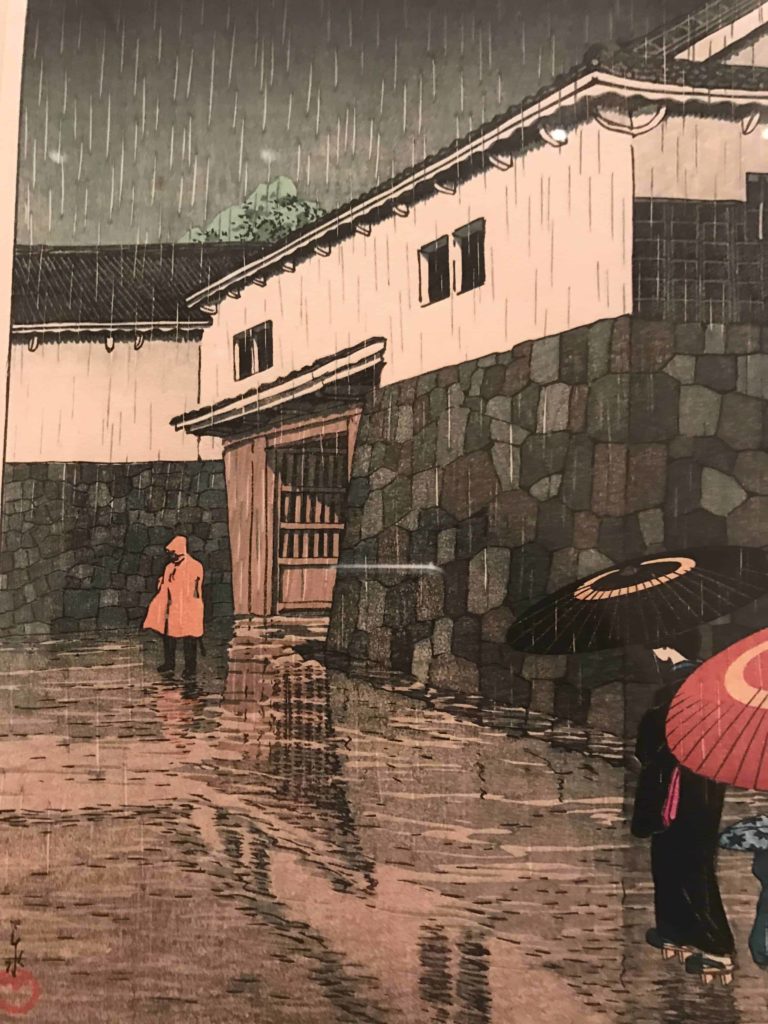

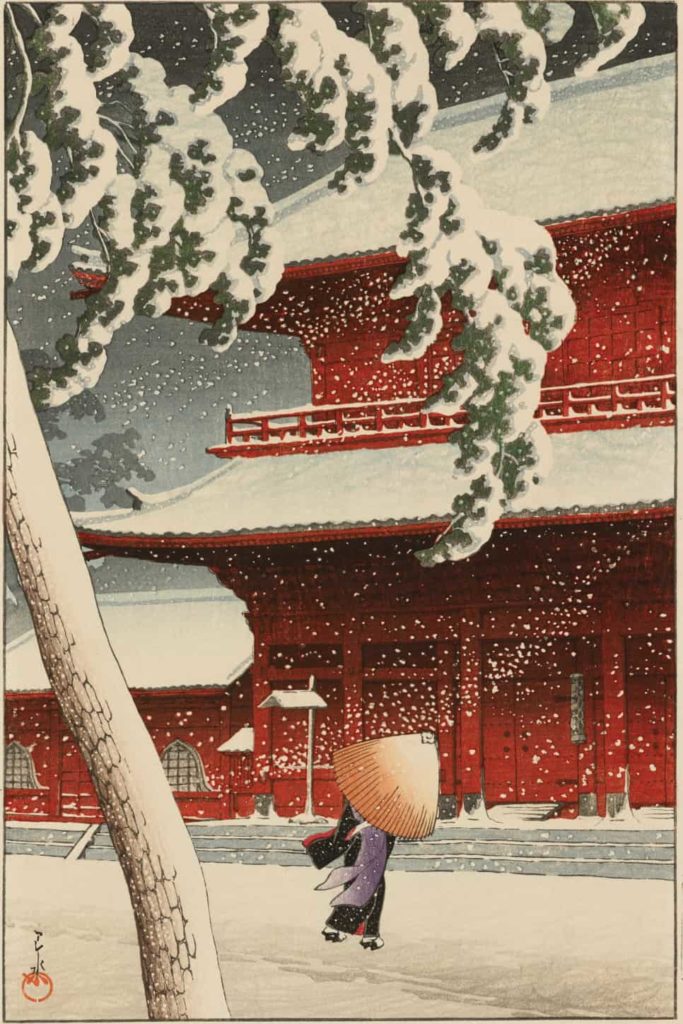

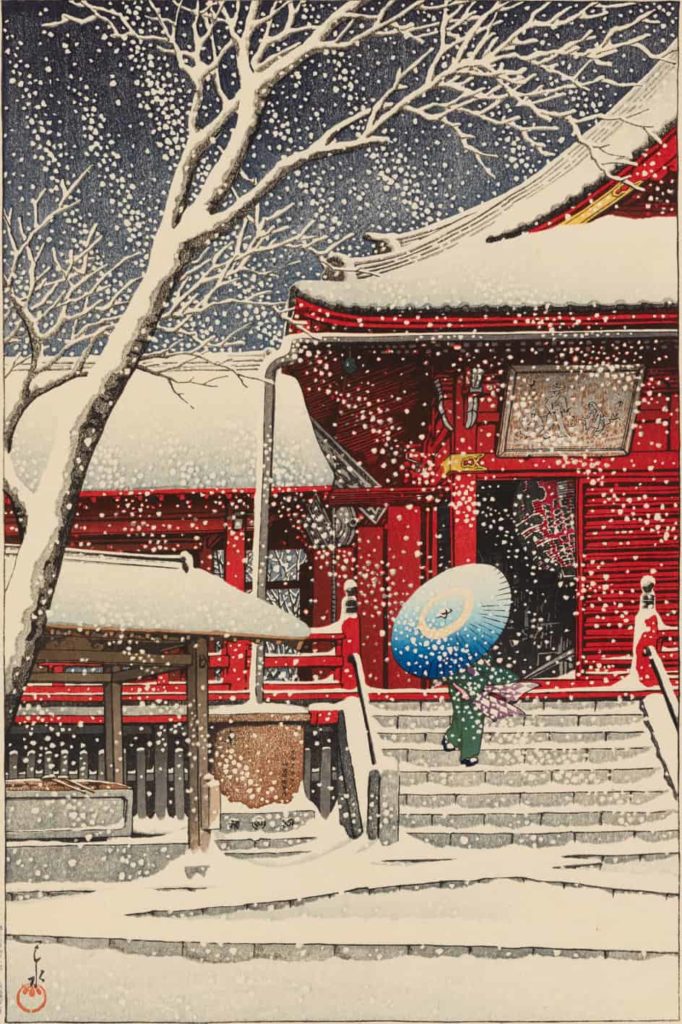

Among Shin-hanga artists, Hasui Kawase (1883 – 1957) comes strongly into this show, as he does in the art movements in his lifetime. Japan named him a living national treasure in 1956.

I wonder how he composed a scene like this in vivid, shifting color. If the woodcarver shapes the blocks and the printer sets the inks, how does Hasui guide the work? I can feel his eye in it, his own and different from his contemporaries — Yoshida Hiroshi’s city streets at night have another kind of intense light. And I wish I could find Hasui in his studio, the way I’d sit down with an artist in North Adams, and talk with him.

The closest I can come right now is the Clark’s library, where I can sit at a table by a long window, as the night comes early, and pour through Water and Shadow by Kendall Brown. He says Hasui studied Japanese painting, nihonga, and Western painting at the Aoibashi Yoga Kenkyujo (art school) — life drawings and paintings in oils and watercolor, pigments and inks.

Leonard sees these influences blending in Hasui’s work, in his perspectives, in the way a space can open into three dimensions, and the balance of a scene, as people move small in the distance beside a natural element, marshland along the coast or a centuries-old temple in the snow. She talks about the play of color and light and the control of line.

For his prints, Hasui would sketch and then paint in watercolors, Brown says. Sometimes he made finished paintings, and sometimes studies in color, genga, as guides for the prints. Then he worked closely with the printers and woodcarvers. He would go over proof sheets and debate over fine shadings of color — once for as long as four years. He would send back notes in the margins on how to get the effect of a puddle in the rain or a gleam at dusk — “blur the lights with red.”

He would travel, too. He always sketched and painted a place from life. He would go alone, Brown says, leaving his wife and his friends and fellow artists in Tokyo. His publisher would send him across Japan

He could cross the water to to Miyajima and come to Daisho-in, the Buddhist temple, and talk with monks making the pilgrimage from Tibet, and maybe see a sand mandala in the making. He could climb Mount Misen and look out from the top to see as far as Hiroshima.

Or he could sketch by the bay at Matsushima. The islands of steep rock are weathered into natural arches, and they carry pine trees and red bridges. Later (in and after the war), as shin-hanga ebbed and he worked more on his own, he would paint his own scenes in watercolors. I wonder whether working with a publisher set limits on him and how his later work might have grown.

Hashimoto Okiie, Young Girl with Iris, 1952. Image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

And how did Saito feel about working on his own — did it feel like a constant struggle to find the resources to make and show his work — did it feel like independence? Sōsaku-hanga artists, with their edge of Modernism and abstraction and homemade blocks, make me think of artists in New York and Paris who were holding their own shows because museums wouldn’t let them in. They were working in warehouses and apartments and showing in classrooms at NYU … and were Saito and his friends in Tokyo doing the same in their own way?

He grew up in Hokkaido, far enough north for taiga forest like Nikolai Astrup’s western Norway, or northern Canada — at its coldest, it can see 30 feet of snowfall in a winter.

He came to Tokyo at 23, working as a sign painter, and when he discovered wood block printing, he would not have had the resources Hasui drew on for years. Ted Hatlen, a friend who spent time with him in his studio recalls him working with a kiri, a carpenter’s awl. (As a professor at UC Santa Barbara, Hatlen writes the central essay in Kiyoshi Saito: Woodblock Printer, one of the Clark’s two books about him.)

Saito made his earliest series of prints as images of snow and shadow — he called them Winter in Aizu, where he was born, and where his family evacuated during the war. Later he would walk through the gardens and architecture of Kyoto, Nara and Kamakura and study Buddhist haniwa carvings. I wonder what drew him to unglazed terra-cotta figures more than 1600 years old.

The earliest Japanese wood block prints are Buddhist, according to this show, and something in the vigor and organic textures of those early images seems to call to Saito’s work. I feel a kinship in his colors, charcoal and dark chocolate and red ochre, and his stark, clear forms. In the dense crowds of Tokyo, in the rapidly industrializing core of one of the largest and most populated cities in the world, in the hard years after World War II, I wonder how he might have felt standing in a garden in the oldest zen Buddhist temple in Kyoto … and what he might have come looking for.