A serpent leans its head through an opening in the stone. In its open mouth, a man’s head is floating with closed eyes, as though he is asleep. A maize god looks down from above, wearing a headdress of corn husks.

At the center of a gallery at the Williams college Museum of Art, sculptures on a central pillar hold some of the light and orientation they would have held where they were made, in a pyramid in southern Mexico.

They belong to a faith where everything that moves has a life force. People have more than one soul. And the line between people, gods and animals can shift like a river in the rain.

Williams College Museum of Art has opened Seeds of Divinity, an exhibit of works from artists in five civilizations in Mexico and Central America — the Maya, the people of Teotihuacán, the Zapotec, Nayarit and Aztec.

Antonia Foias, chair and professor of anthropology, curated this exhibit with her students in a fall course.

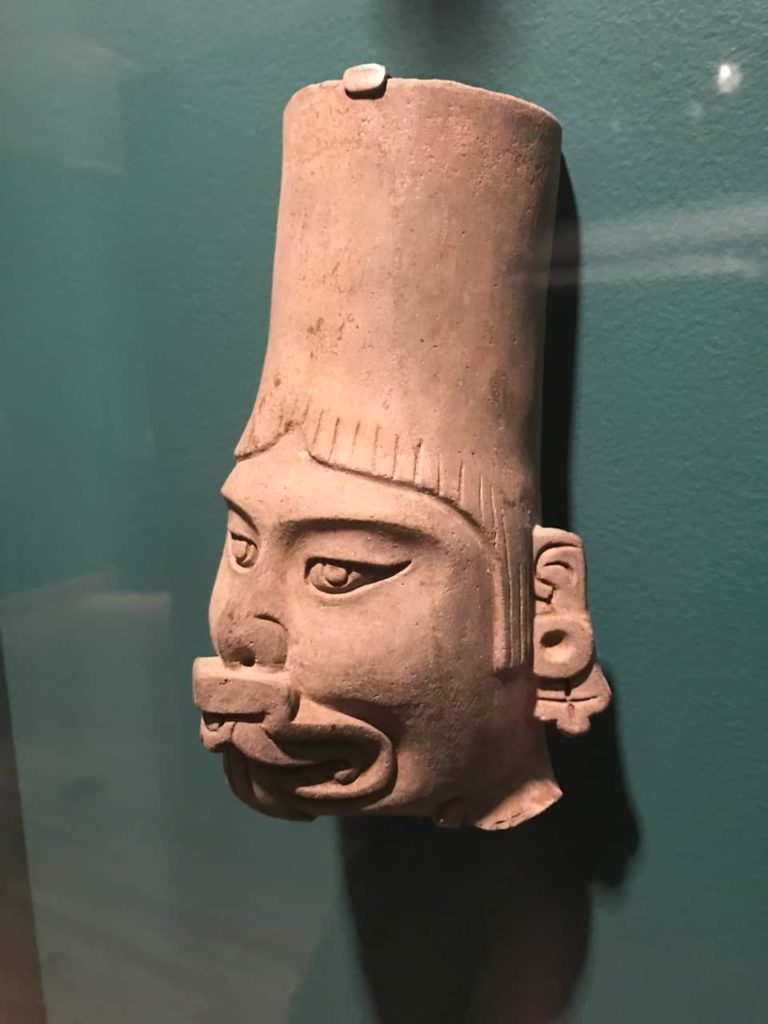

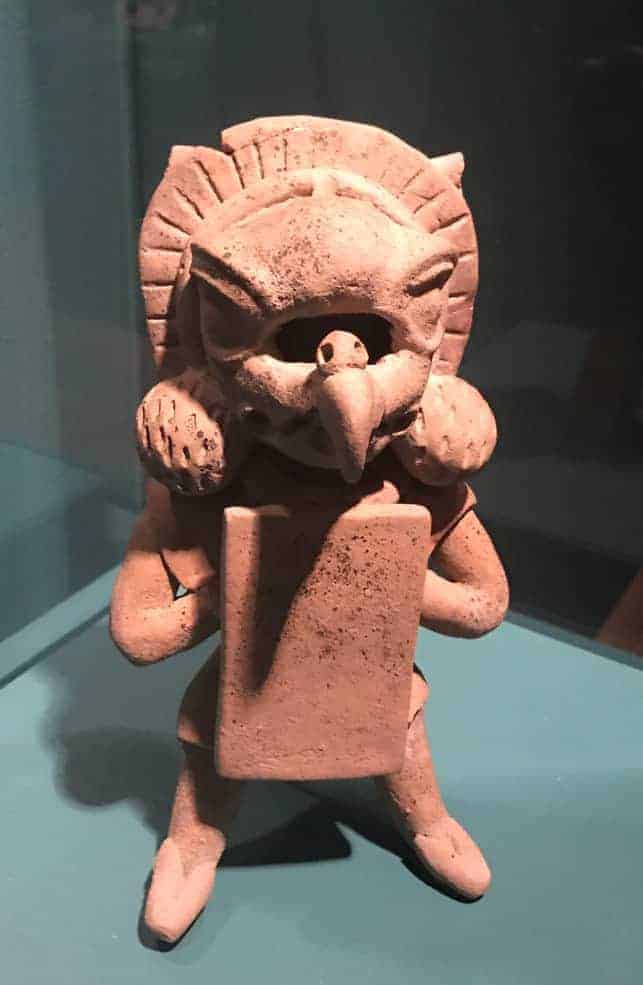

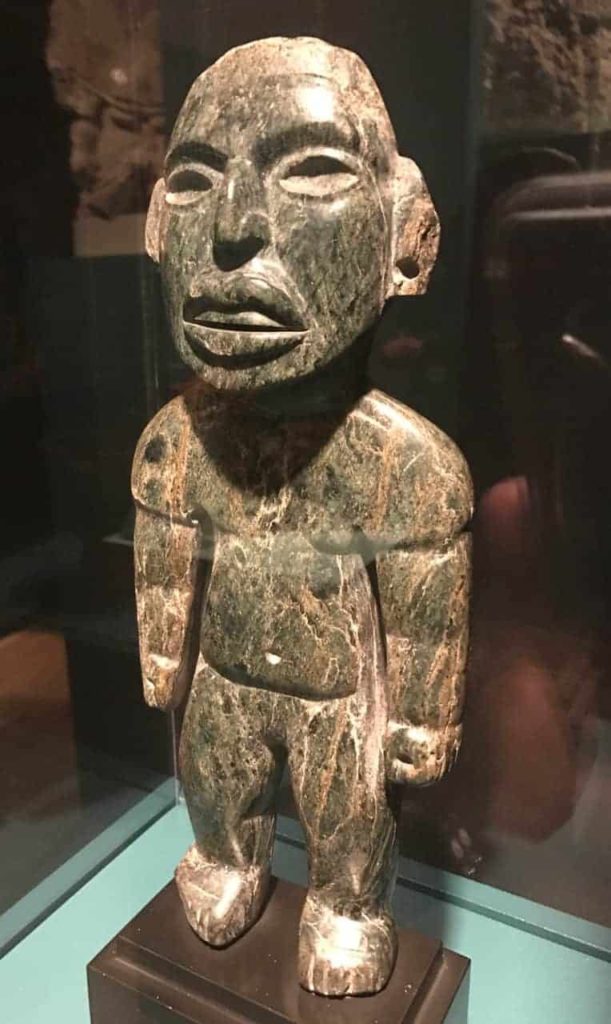

They began with a question, she said, as she walked among figures in clay and polished stone, offering bowls, a terra-cotta whistle, a clay rattle and rasp: Who are the gods, and how do people see them, think of them and interact with them?

These objects belong to people both past and present, she said. The artists who made them lived anywhere from 2300 to 200 years ago, and the faiths and people they come from, Aztec and Zapotec and Maya, are here and evolving.

More than seven million Maya live in Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador and Honduras today, and more than a million people speak Mayan languages.

“It’s a point we all wanted to make,” Foias said, “… these ideas about the universe, the world, humans and animals and the supernatural are still with us. They are alive.”

These faiths share a belief in a life force, she said. They see it in everything in the universe that moves. Mountains shake in earthquakes. Clouds cross the sky. Rain falls. Plants grow and pollinate, seed and die. They generate a force people take part in. And animals are so close to humans, they may share a body or a spirit.

Humans often have many souls, Foias said, four among the Maya and three among the Aztec. People have one soul in the breath, and one in the heart and the blood — the Mayan ch’ulel is connected to the pulse. One soul may take form in the heat of the body. And one soul takes an animal form, an animal spirit, an avatar.

She traces these beliefs in the details of a figure’s body. A stone woman touches her pregnant belly. A creature half bat and half armadillo invokes Venus as the planet comes and goes, like them, at dusk and at dawn. The sculptures themselves tell stories.

“Objects are central to what I do,” Foias said. “For my students, it’s hard to take them to a Mayan site to excavate.”

So she led them to explore artifacts from WCMA’s collection, the Worcester Art Museum and Yale University.

She also talked with them about how these colleges and museums come to have collections of artwork from Mesoamerica.

In the 19th century, when Williams had no museum and no science faculty, a professor and a group of students formed a secret society — the Williams College Lyceum — to study the natural sciences. They formed expeditions, including an 1871 trip to Honduras and Belize, and they brought back artifacts.

That means often Foias and her students do not know where a sculpture came from, or who made it and when. These figures have been taken out of place. Some have lost the clothing and ornaments they would have worn.

A few records still survive from 500 years ago or more, but they are in fragments. Since the 1500s, Europeans have burned books and stolen artwork wholesale, and the diseases they brought have destroyed cities and communities and millions of people.

But people survived, and ideas survived — astronomy and mathematics, calendars and music, even a genre of Aztec poetry given wholly to flowers.

So in part, Foias and her students can understand how people have seen the figures in this room, when they lived in homes and temples. When people burned herbs in them, played music with them and prayed looking up at them, then for a time these vessels could become gods. A sculpture or an image of a person or a god carries their soul.

“Your being doesn’t stop with your skin,” she said. “It can extend to objects that depict you. And they are brought to life through rituals.”

One ritual they called opening the eyes. Like Egyptian or Hindu sculptures, the figures here would have had eyes of obsidian, pyrite or polished shell. Their eyes would reflect the light.

And when the artist sets in the irises and pupils, as the last touch, then the soul enters in. The sculpture becomes, for that time, a living incarnation. And in that time, gods and people can influence each other.

People may also take in the essence of god, in a communion.

“When they eat corn, they are eating the body of the maize god,” Foias said, “and so they have to give something back, in worship, in prayers and in earlier times, in blood. Blood was where you found the life force.”

And that reciprocal exchange keeps the universe whole.