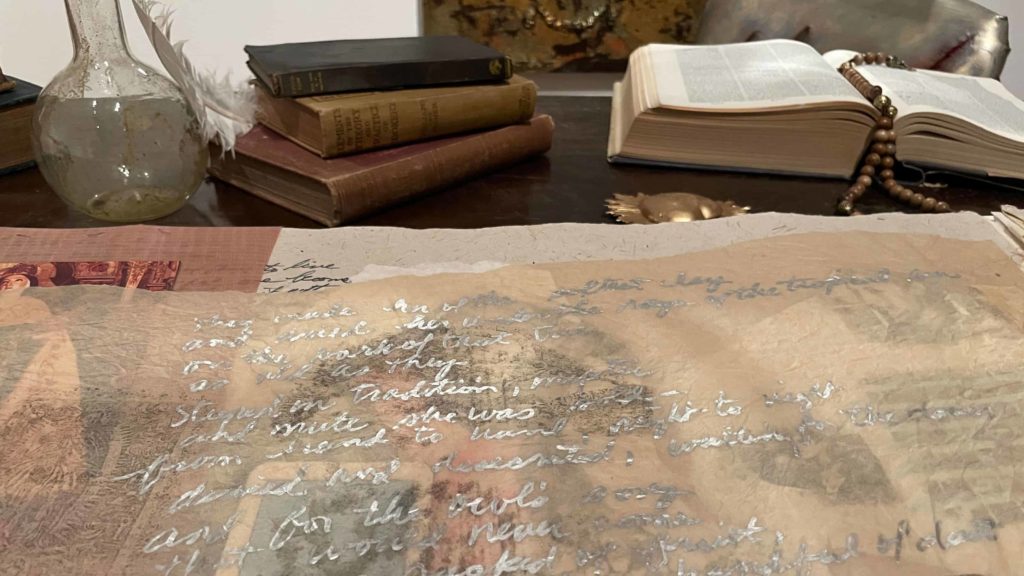

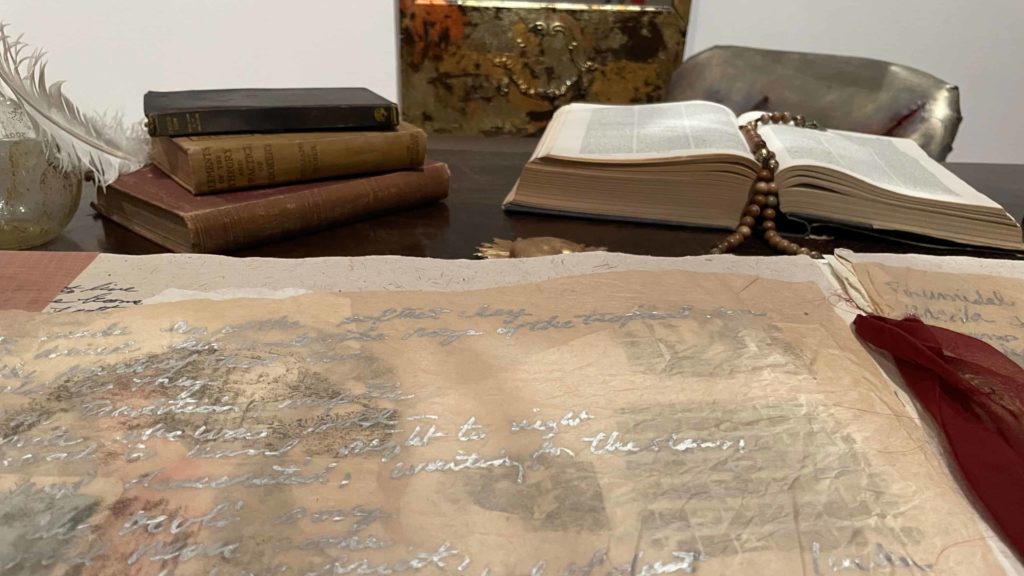

Rounded glass bottles with tall lips lie near a microscope and wooden beads strung like a rosary. Long overlapping pages spread out in different kinds of paper, written in different inks — a light translucent membrane lies over a dark red sheet as thick as cloth, and broad silver script flows over a fine black tracing as though someone has drawn a room walled in shelves filled with books and paintings and carved panels.

WCMA has reopened, after more than a year closed in the pandemic, and I am transfixed by Amalia Mesa-Bains’ Library of Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz.

I’ve been walking through the galleries up here, surrounded by women, artists challenging and encompassing and closely observing the world — and by libraries. Mesa-Bains is an internationally known Chicana artist living in California, and here she is creating a world, imagining the mind of a woman who lived three centuries ago.

She creates sacred spaces, like ofrendas, home altars to honor and remember someone loved. And she has made this one for a nun born in San Miguel Nepantla, Mexico, in 1651.

I knew Sor Juana Inez by name. Years ago my brother gave me one of her a poems that he had translated in high school Spanish.‘How have I offended you (world), when I only intended to put my understanding in beautiful things? …’ So I knew her clarity — but I hadn’t realized her humor or her passionate curiosity.

‘I looked on nothing without reflexion; I heard nothing without meditation, even in the most minute and imperfect things.’ — Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz

She studied Greek and Latin and Nahuatl, the language of the Mexica, the Aztec, and she wrote poems in Nahuatl. She wanted to dress as a man so she could go to university — and she chose to enter a convent so she could still talk with scholars and write poems, plays and music — at least for awhile.

She met pressure there, inside and outside the order, and she answered a public attack with a public declaration of the vigor and joy in her mind. When her superiors tried to forbid her books, she says, she studied the perspective lines in the wall of her room, the force that leads a top to spin in a spiral, the chemistry of quince syrup and the geometry of the harp. Any sound or movement could lead her to pick up an idea and turn it over and strike it on another like a flint and steel.

“I studied all the things that God had wrought, reading in them, as in writing and in books, all the workings of the universe. I looked on nothing without reflexion; I heard nothing without meditation, even in the most minute and imperfect things.”

What books would she have had in her library while she was alive, what scientific instruments and maps?

Here, Bains has invoked her with a mirror in the shape of a triptych or a wide-sleeved robe and a desk covered with objects. Ideas spill against each other — a Copernican drawing of the solar system and a book on evolution. A globe sits turned so that as I walk up close to it I am looking at the coastline along Djibouti and Eritrea, the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea.

And here is a cookbook like an inside joke. In her letter championing learning, she challenges her accuser, who would banish her to ‘womanly’ spheres, “… And what shall I tell you, lady, of the natural secrets I have discovered while cooking?”

She describes the transformations of an egg in butter or in syrup as vividly as she recalls her dreams, when her imagination would “work more freely and less encumbered, collating with greater clarity and calm the gleanings of the day, arguing and making verses.”

I wonder if she had Nahuatl poems in her library, when she wrote the sonnet I still have on my desk, about finding richness in thoughts, not in things.

In Nahuatl, a writer’s poems, her words, her breath, become the highest kind of art, (according to Charles Mann in 1491). Two hundred years before Sor Juana, the poet Ayocuan Cuetzpaltazin describes writing poetry as natural and clear as birdsong — he set poetry as the one real thing in a quick life, and the act of creating as the closest humans come to knowing God.