If Sol LeWitt were alive today, would he be working with a programmer in fractal algorithms? Listening to the way he worked, it can be easy to imagine him experimenting in the digital age. He would take a line or a shape and set it to repeat. He would imagine space filled with vibrant color, primary reds and blues and yellows, orange and green — he would define a pattern and set it in motion, and let it move … And then he would put it in someone else’s hands to make the colors physically real.

People often recognize LeWitt through his huge and vivid wall paintings, but this spring the Williams College Museum of Art is taking a look at his life and his work through his printmaking. Their new retrospective, Strict Beauty, follows LeWitt across more than 40 years.

Seeing a more complete body of work allows new connections, says David S. Areford,

guest curator and professor of art and art history at UMASS Boston, and it has given him a new perspective on LeWitt as an artist.

A pattern of tapering triangles and diamonds in autumn colors, one of Sol LeWitt's series of Complex Forms prints, appears in Strict Beauty at the Williams College Museum of Art. Press image courtesy of WCMA.

“I used to think of him as cool, intellectual and detached,” Areford said.

Now, as he takes a broader and deeper look into LeWitt’s work, he thinks of LeWitt as deeply concerned with creating an engaging experience. His works draw people in with their vast scale and hues and energy.

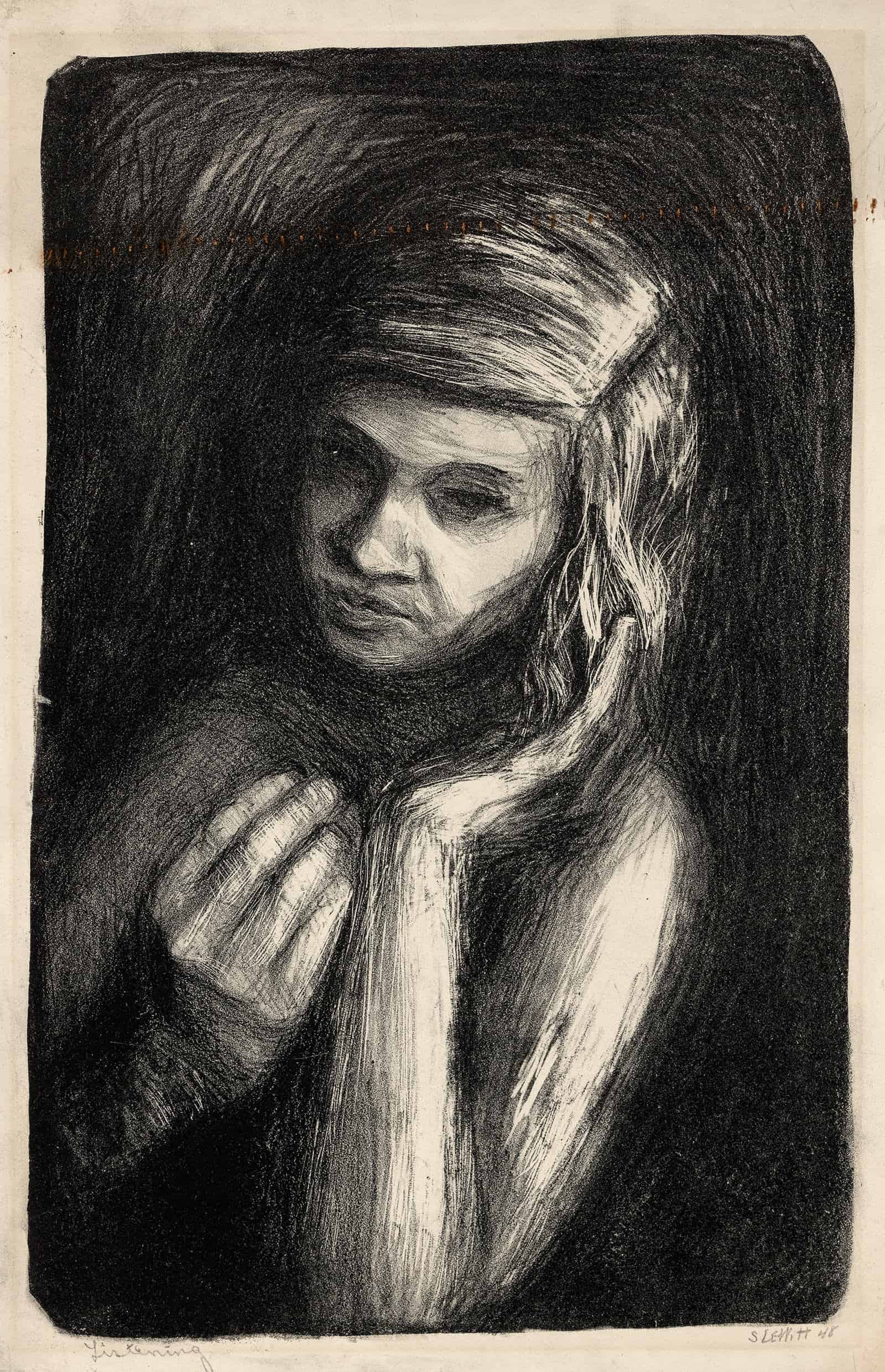

The opening prints here he thinks will surprise people. Anyone expecting massive geometric color will walk in face to face with lithographs of a woman cupping a hand to her ear, a group of people tired and self-contained on a bus, a man hunched under an umbrella and reading an election notice in the dim drizzle, a caricature of a pontificating politician.

Sol LeWitt's lithograph Listening, a woman with her hand cupped to her ear, appears in Strict Beauty at the Williams College Museum of Art. Press image courtesy of WCMA.

They are graphic and experimental, Areford said, portraits and scenes in lines like charcoal, with layering and shading and textures. They show the influence of the 1930s and 1940s in their socially conscious and urban scenes, some satirical and some showing a sense of family or intimacy.

They are some of LeWitt’s earliest print work, made between 1947 and 1954, in college at Syracuse and in the early years after he graduated. He would have been a few years too young to serve in World War II Areford said. He started college at 16, and he was 17 when the war ended, in 1945.

What was it like for a young secular Jewish art student, growing up in a community that carried the fear and the weight of the Holocaust, coming to class on campus with older GIs who had served oversees?

LeWitt discovered lithography as a junior, Areford said, and took the course four times — he embraced printmaking as a democratic art form, and it would continue to matter to him as a way to reach people with his work.

In the years that followed, he would struggle to be seen, Areford said. The show has only one print from LeWitt’s first 10 years in New York, while he was holding down day jobs, working in graphic design and architectural firms, and art was something he eked out in his spare time.

‘I used to think of him as cool, intellectual and detached.’ — David Areford

By the 1970s, he was making silkscreens. He had begun making wall drawings and structures as well, Areford said, and also books and photography, works on paper, washes and drawings. He experimented in different media all his life, and in many kinds of printmaking through the years.

Often he worked with a printmaker who would do the hands-on making. LeWitt said he wanted to remove himself from the work, Areford said. He wanted a sense of order. He wanted to “set an idea in motion” and let it go, and he liked to be surprised by the outcome. By an idea he meant — not a thought or a feeling, no sense of his own character or experience, not a mathematical equation or expression — but a pattern.

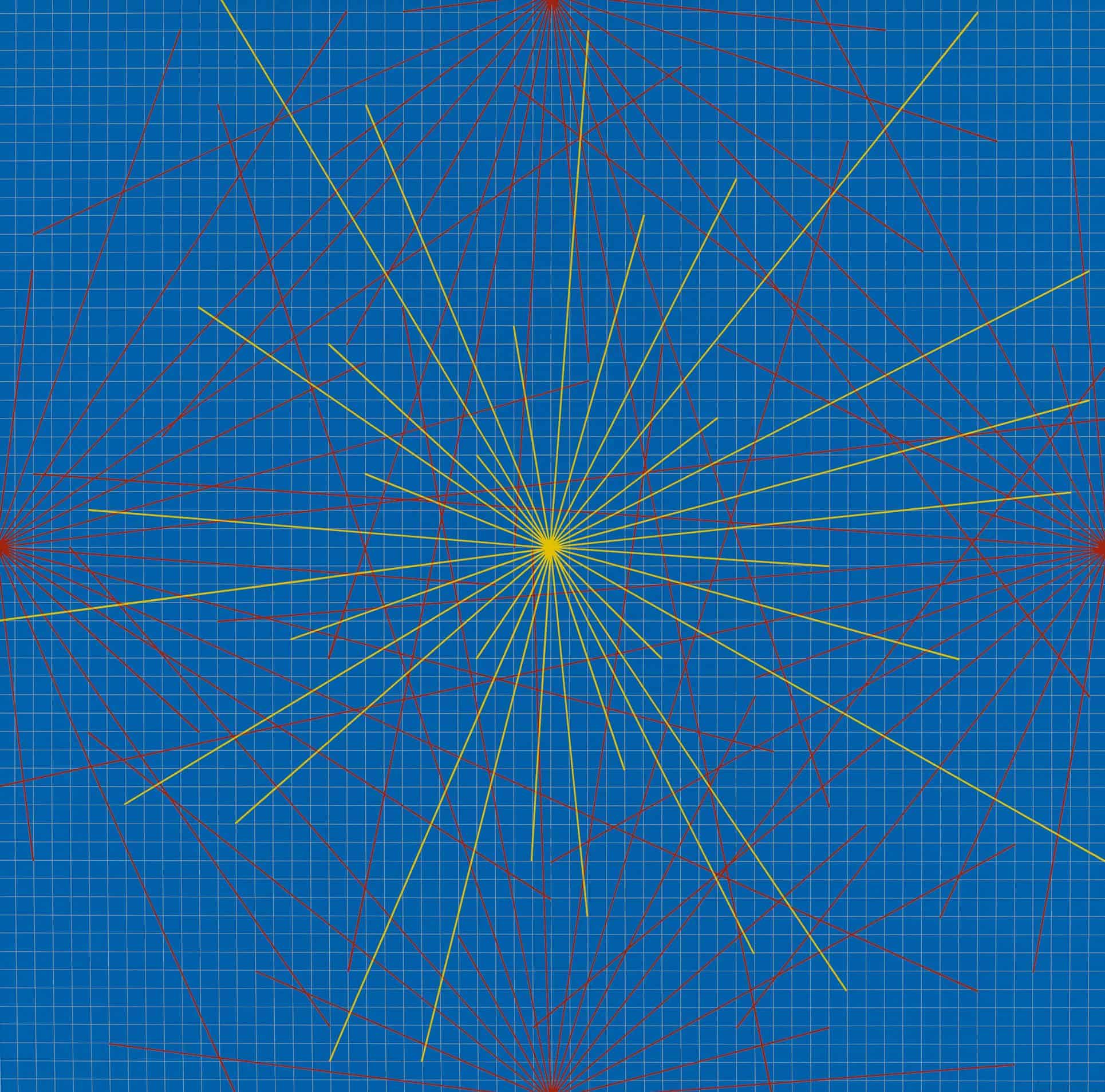

Sol LeWitt's silkscreen Lines in Color on Color to Points on a Grid appears in Strict Beauty at the Williams College Museum of Art. Press image courtesy of WCMA.

A series of prints show radiating lines over solid bright color. LeWitt talked about geography in these images, and movement across space, Areford said — LeWitt compared these silkscreens to 14th and 15th-century navigational charts, but they hold no sense of physical or identifiable places. They have more in common with the special effects for hyperdrive in science fiction films — lines across a vacuum of space. LeWitt called one of these prints “Star Wars.”

He was interested in a very simple visual vocabulary, Areford said. Early on, people thought his work was mathematically complex, and he said not at all, that he knew nothing about math.

He might share an enthusiasm for literature or music, Samuel Beckett, novels and plays with a sense of illogical or irrational. In his artwork, he felt a tension between control and relinquishing control, Areford said. He would take a line or a geometric shape and set a pattern, and repeat it according to rules for color, size, shape, orientation.

And then Areford sees a shift in LeWitt’s vision.

“He begins to loosen his rules,” Areford said.

It’s the late 1970s, and LeWitt was in his 40s. He had met Carol Androgio, who lived near him in New Jersey and had family in Italy. They traveled together, and eventually they moved to Italy together. They married in the early 1980s had two daughters.

Areford suggests an influence in the marble contrasts in Italian architecture. Did these changes in his family and emotional life influence his artwork as well? As he gets to know the woman he will marry, as they move to a new country and their children are born, his prints shift from the hypercontrolled lines and solid backgrounds in the 1970s silkscreens to these fluid forms and vivid colors.

WCMA’s Deputy Director for Curatorial Engagement, Lisa Dorin, agrees, laughing, that energy and color grow in his work in these years, and seeing LeWitt’s work like this, unfolding over time in the context of his life, raises questions like this. In Italy too, Areford said, LeWitt asserted his Jewish heritage, as when he faced social pressure to have his daughters baptized.

Sol LeWitt's Shul Print, a vividly colorful Star of David, appears in Strict Beauty at the Williams College Museum of Art. Press image courtesy of WCMA.

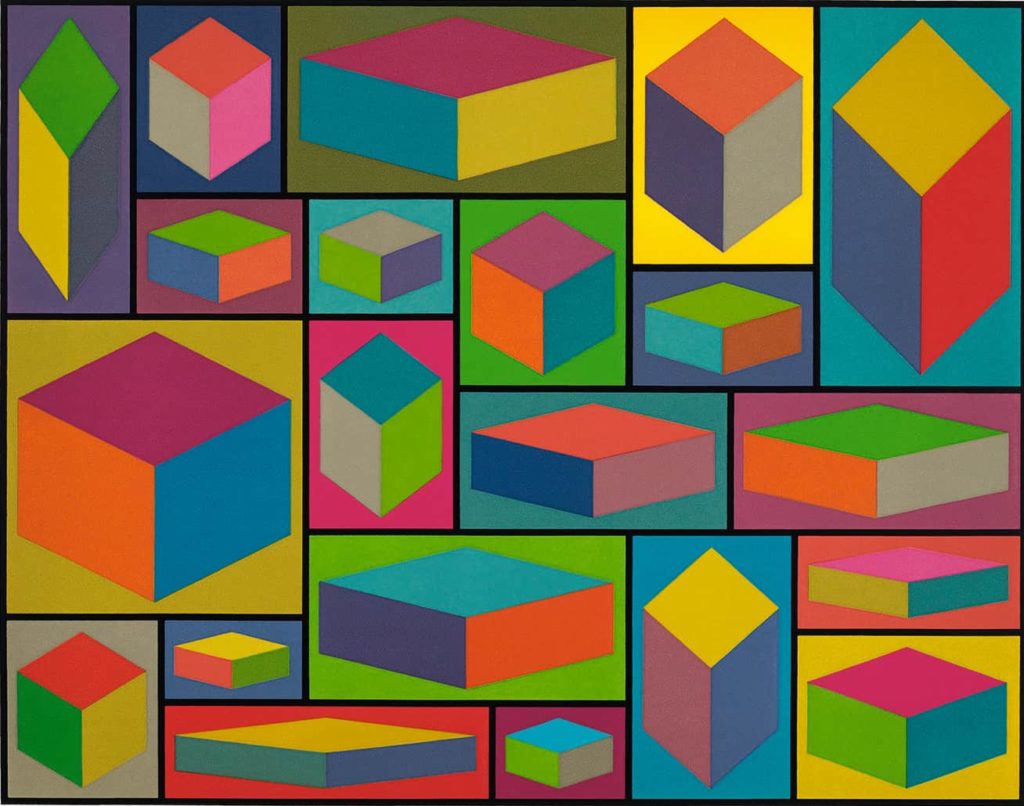

By the late 1980s, he was moving into complex forms — double pyramids, asymmetric and subtle in color, intuitive aquatints and large, asymmetrical shapes drawn as though they are three-dimensional. His patterns become irregular and his lines more curved. Some of these prints have an almost a crazy-quilt quality — triangles and diamonds and rhombuses bending to fit together as though the surface is folded.

For some of these prints with more fluid shapes, Areford said, LeWitt drew the original freehand, and then assigned facets and directions for color. He was working with layering transparent colored inks.

By the 1990s he was experimenting with bolder, graphic forms. On some level, Areford finds these impersonal — they have no sense of a hand drawing a line. These prints are “opaque, not nuanced or layered,” he said, showing a bright 1998 silkscreened poster for the Mostly Mozart festival at the Lincoln center.

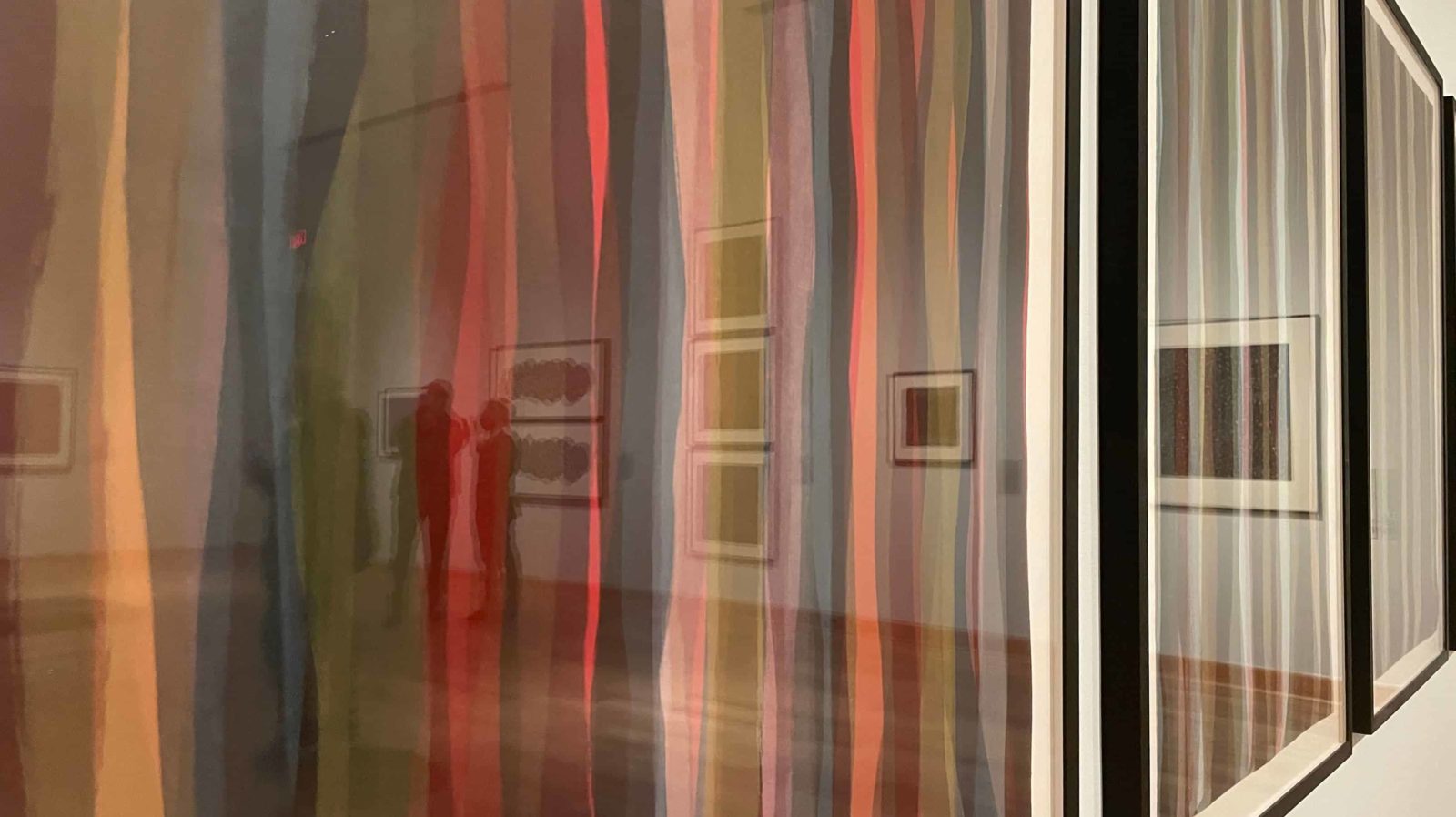

Curves of color form Wavy Brushstrokes Superimposed, one of Sol LeWitt's later prints, in Strict Beauty at the Williams College Museum of Art. Press image courtesy of WCMA.

Here are the vivid color people often recognize from his wall drawings moving in bright bars or curves and mazes. Areford traces influences from abstract artists like Mondrian, with his broken bands, rhythms and syncopations in patterns of color.

LeWitt is experimenting with more complex shapes now. Some are playful, and some open-ended, as in a series of shapes within a cube, which could go on infinitely. Some are some symbolic. Beside images of half-architectural intersecting planes, Areford has set the Star of David LeWitt designed in 2005 for Congregation Beth Shalom Rodfe Zedek, his local synagog in Chester, Conn.

“It’s the only building he designed,” Areford said, “and it was based on Eastern European wooden synagogs. And he made this painting for the cabinet that holds the Torah scrolls. The cabinet opens and the star expands on both sides. It’s a celebratory expression of his heritage.”

The star is vividly bright. But now, in these later years, he is shifting his patterns again.

In prints he calls Brushstrokes, the shades are blurring into each other like abstract oils. He tells his master printer to move the block across the page at intervals, or turn it 180 degrees and re-print, superimposing layers of ink. And here thick lines are curling in one color over a another like the leading in a stained glass window, suggesting the abstract forms of leaves, or the surface of a river.