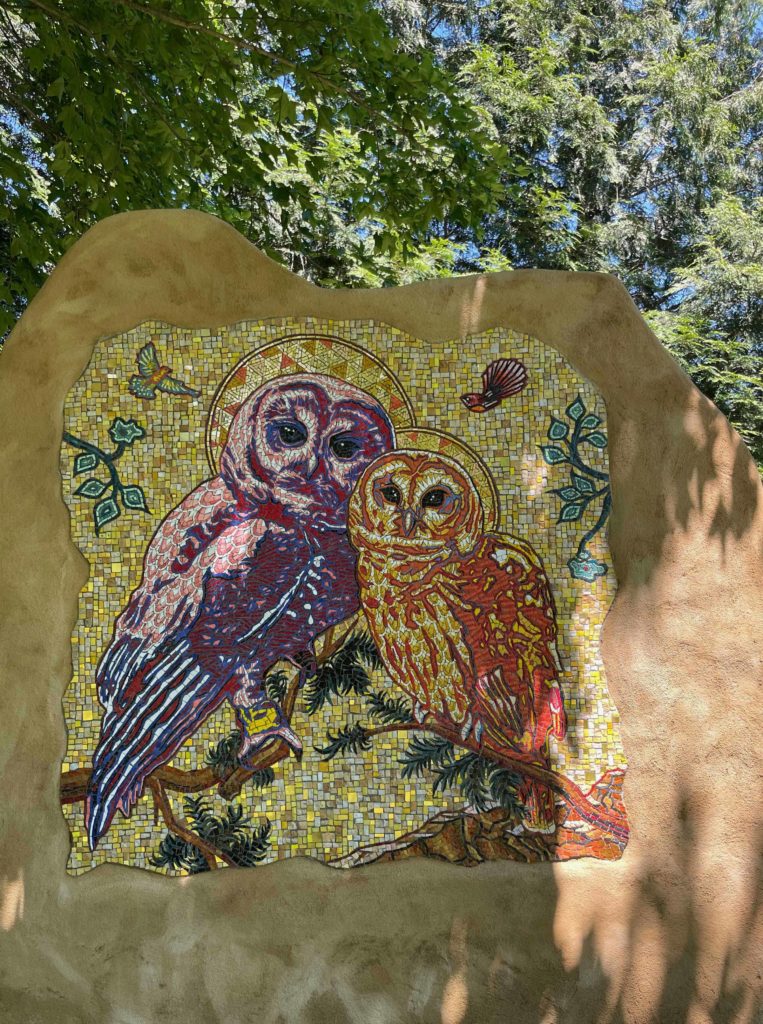

Glass tiles gleam like stone under water. They reflect light in wide eyes. Two owls look out of a mosaic in a stucco wall that seems to ease into the land around it, like a new outcrop from a vanished temple, with plants growing in the crannies and at its feet.

Interdisciplinary artist Peter Gerakaris has learned a new medium as he has worked over the last year to prepare a new work for Taking Flight, this summer’s sculpture show at the Berkshire Botanical Garden in Stockbridge.

Outdoor sculpture is growing across the region this summer, as the pandemic begins to ease and museums reach out to people eager for safe ways to come outside and find color and creativity. New collaborations and expansions are emerging.

Immi Storrs brings her earthy and visceral bronze sculptures to the Berkshire Botanical Garden.

In Vermont, the North Bennington Sculpture Show partners with Bennington Museum, and Salem Art Works comes to the Southern Vermont Arts Center, gathering more than 100 works between them, said Jamie Franklin, curator at the Bennington Museum.

In the Berkshires, public art is growing far beyond the ongoing work at Art OMI in Ghent, N.Y., and Turn Park in West Stockbridge. The Clark Art Institute opens a whimsical exhibit of Claude and François-Xavier Lalannes’ bronze sculptures, and SculptureNow returns to the Mount. In early July, Chesterwood will open a new summer show, Tipping the Balance: Contemporary Sculpture by John Van Alstine, and Enchantment will fill the grounds at the Norman Rockwell Museum with dragons and sylvan gods and goddesses, to accompany their indoor exhibit of fantasy and magic.

At the Botanical Garden, well-known art collector Beth Rudin DeWoody is gathering a unique flock of birds. She suggested the idea in response to the garden’s theme of flight this summer, and she has reached out to artists she knows well, she said —Concha Martínez Barreto, Tracey Emin, Rachel Owens, Ian Swordy.

Immi Storrs casts her works in bronze, often textured with an organic feel like bone or clay and marked with her fingerprints. They are earthy and visceral, life-sized birds, some vividly lifelike and some more abstract, seeming to move with an energy of wingbeats. A crow hovers over eggs in a nest in a shaded corner near the pond. A songbird alights high on a pole.

She is delighted to see them outdoors, she said.

On a larger scale, Owens has also shaped a raven. DeWoody sees both a natural form and a commentary on the toxic substances poisoning the environment — this bird seems made of surfaces as slick an oil spill.

And Gerakaris is drawing on his own Greek heritage in a bright new work like a WPA mural or a fresco painted in fresh plaster — but this is a mosaic in glass tile. It is one of the few ways to work in color outdoors, he said, in a form that will last.

He has painted monumental murals in the past, but he often works in origami, paint, media that will not hold up in the weather and the damp. To make his first move into sculpture, he is working with one of the top mosaic artists in the country, Stephen Miotto, and his Miotto Mosaic Art Studios in Carmel, N.Y., and Friuli in northeastern Italy.

Together they are scaling up one of Gerakaris’ paintings. It feels like a dream, Gerakaris said, to see his work come together in a new form and to have it here in the vivid outdoor setting of the garden. He remembers coming here as a boy, growing up in New Hampshire.

The owls he brings here, to the lawn and flowering pathways near the Center House, come from a series of his paintings in the style of Byzantine icons, figures set on a rich golden background. But where the Byzantines would have set a saint or a Madonna in the light and place of power, here he sets birds, insects, orchids. And they are all endangered, he said. They are threatened for many reasons, forest fires, development, loss of the forests where they live.

The two here are spotted owls, displaced in the massive logging that leveled the forests in the Cascade mountains.

He finds something sacred and meditative in the processes of making them. Byzantine art has refined over the centuries, he said — the technologies he uses are almost as endangered as the species he honors: gilding, preparing a wooden panel with rabbit skin glue and a sacred red ochre that will receive the leaf with a luminosity that reflects back through the gold.

Feeling the materials in his hands moves him, he said. He feels a connection, hard to put into words but deeply real, between the work, the ideas he shapes, and the physical texture and movement of the making, and knowing the materials and what they can do.

“For a lot of artists, creating work is spiritual,” he said. … You tap into a tradition every time you set off to make one of these works.”

Mosaic too is a Byzantine tradition. He thinks of the walls of Hagia Sophia that have survived centuries and changes of government. He has seen many mosaics in Italy studying abroad and on his ancestral island of Crete, he said, and having the chance to work in this historic form is humbling. To break color into fragments and bring them together into a new whole feels like a kind of rebirth.

Peter Gerakaris' owl mosaic glimmers in dappled shade at the Berkshire Botanical Garden.

He has been continually amazed to see Miotto translate the nuances of paint into these chips of stone. Miotto would call him into the studio to plan and map the progress of plumage on a wing. He breaks the tiles into shards cut and chipped out of a pancake of colored glass, and the tiles are luminous, Gerakaris said. They often hold color behind a glaze layer of glass, and they gleam translucent.

“Each angle of light and time of day has its own luminosity,” he said.

Solid tesserae would seem darker. He and Miotto talked about gold tile for the background, he said, but in shade an opaque tile would have no light to reflect, so they have interspersed gold tesserae with stone and glass in yellow tones, to make an illusion of a golden wall that will look brighter than real gold.

To add to the challenge, he said, Miotto could not put the mosaic together in place. They have had to create it in the studio and move it to the garden, and embed in there a seemingly stucco wall.

The owls stand more than life-size, tall enough to look people in the eye. At this dimension they take on a mythical quality, Gerakaris said. In their expression, in their gaze, he hopes to invoke a spirit, an intelligence that can connect with a human mind, a kind of mutual respect. In that light, the garden itself becomes a sacred space.

“If we’re not caring for nature in a garden,” he said, “there’s no hope for us.”

He imagines the wall trailing with living vines in the center of the garden, around the corner from the bright color of the daylily walk.

As people emerge from the pandemic, he feels a pent-up energy and exuberance building broadly and he hopes to give some of what he has felt in making and in the garden, awe and wonder and a sense of play.

This story begins in an outdoor sculpture story I wrote for the Hill Country Observer in June — my thanks to editor Fred Daley. I have expanded on the Botanical Garden here.