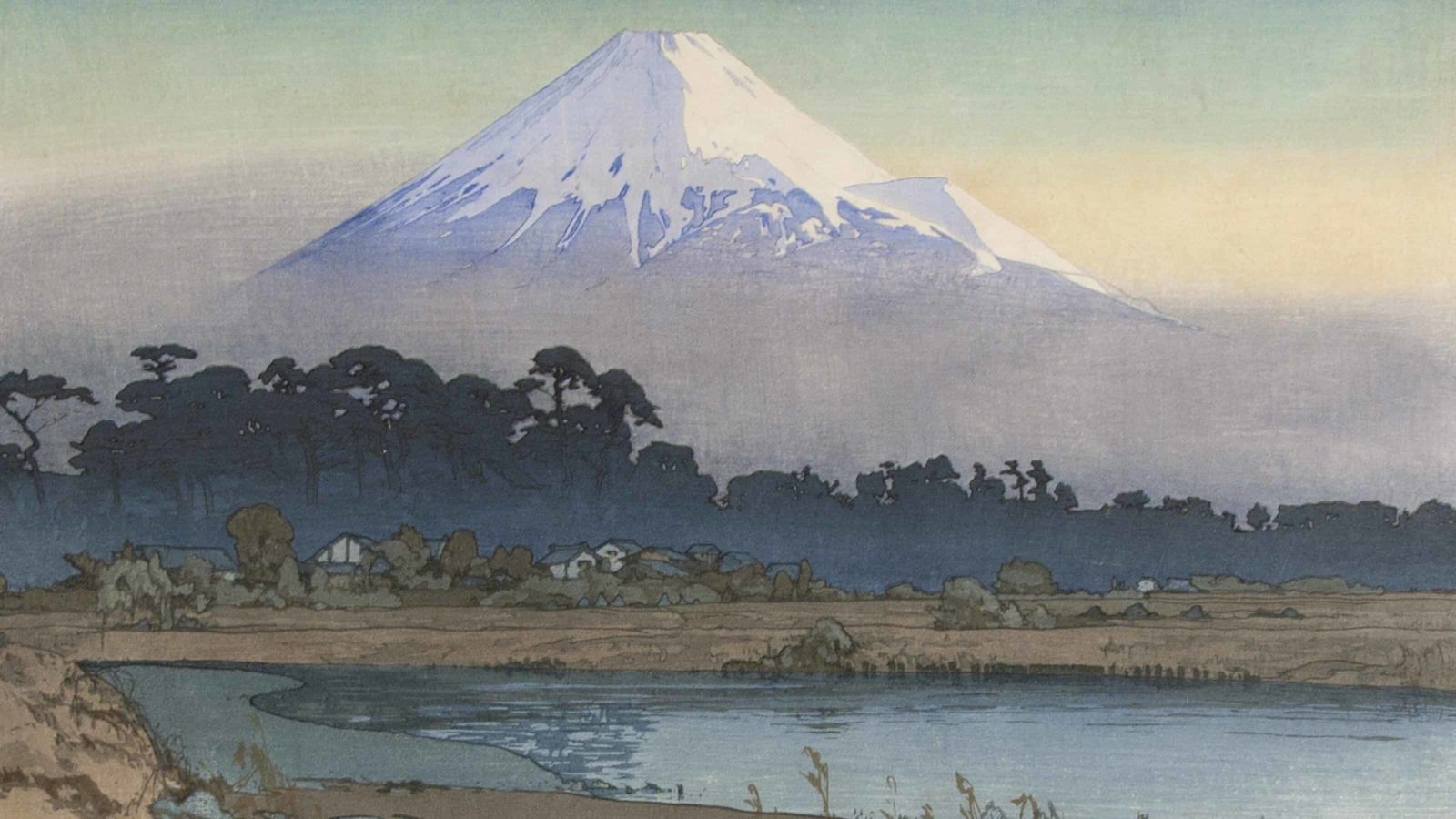

A thief in a tree casts the illusion of a giant serpent. A wave breaks on Miho beach, and sails fill in the wind in the distance. They show as flecks of light against the foothills of Mount Fuji.

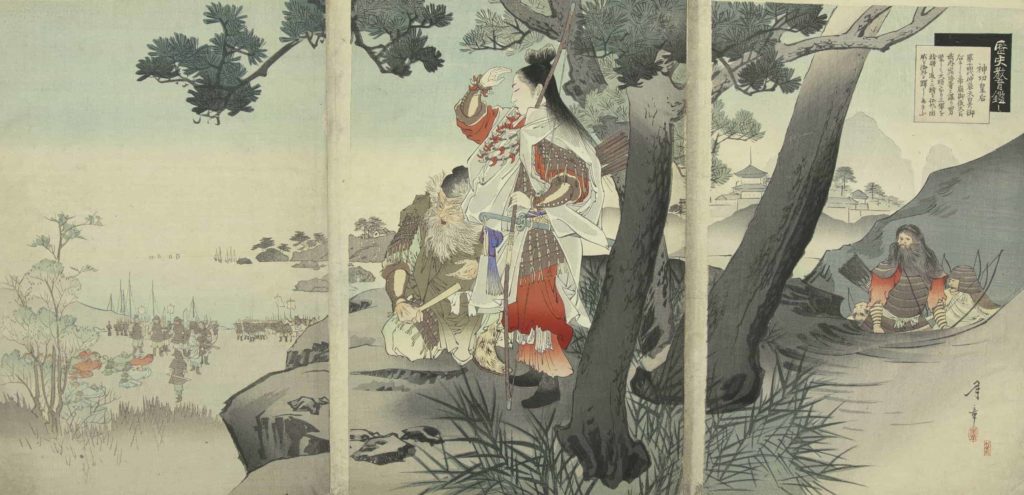

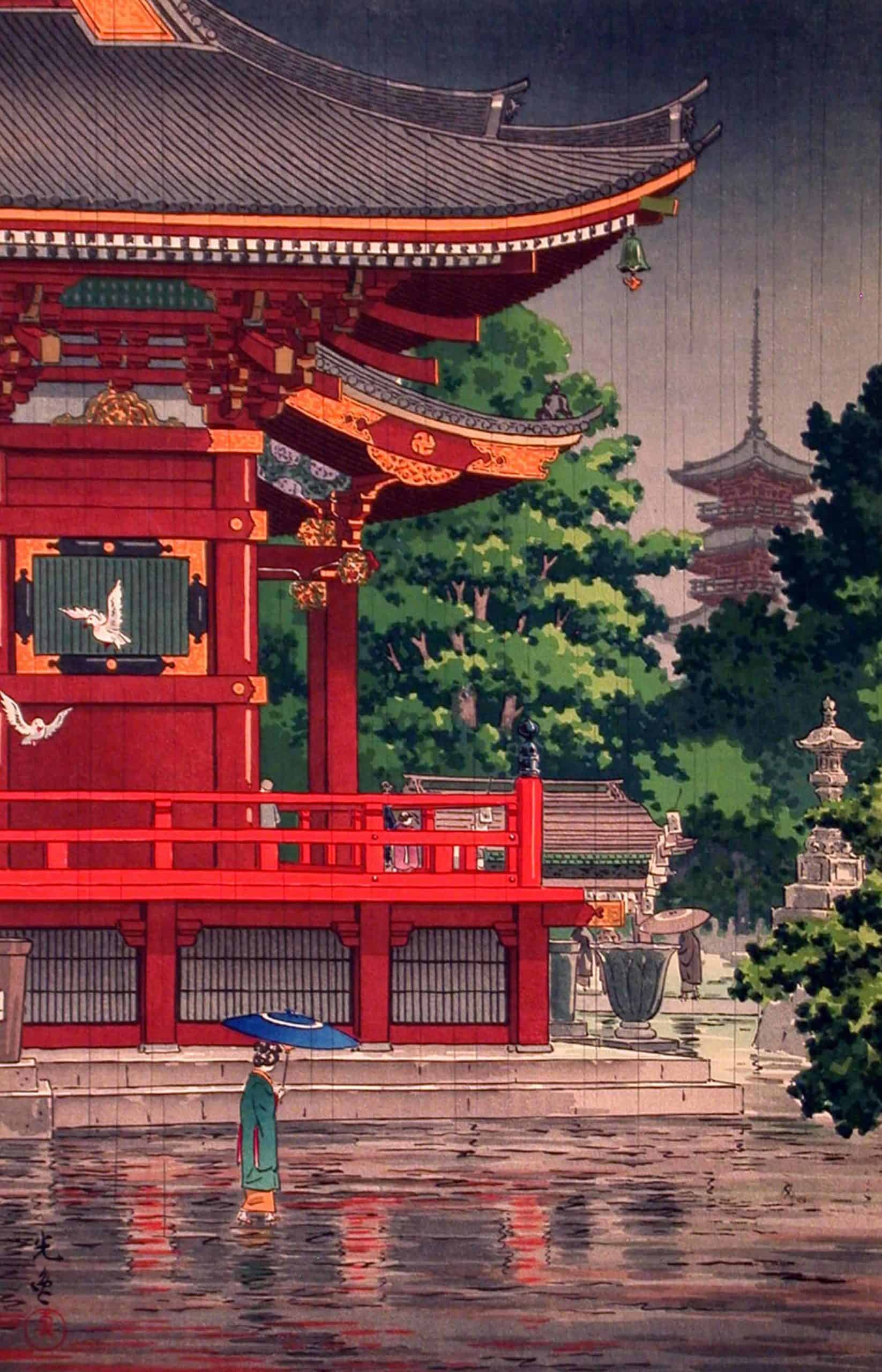

Landscapes and legends fill this room in images of Japanese art from 1720 to 1940. They imagine worlds in fine shades of light and texture as sharp as salt water. Pilgrims approach a temple in the snow. A woman bandit raises her blade.

In 200 years, Japan moved from stability to civil war, and through rapid change to World War II. And in that time a new artform grew until it reached a new audience in Japan and then in a wider world. It moved Impressionists and Modernists in the West, as Japanese artists influenced them and drew from them in turn.

While artists in Paris painted in summer heat in cheap studios in Montmartre and watched the dancing girls at Le Chat Noir cabaret, Ukiyo-e artists in Edo (Tokyo) were refining a technique born in the red-light district.

Two linked shows will follow this trade of ideas in Ukiyo-e to Shin Hanga at the Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, N.Y., and a companion show, East Meets West, from the museum’s collection.

Ukiyo-e began as fantasy, said Jonathan Canning, director of curatorial affairs and programming at The Hyde Collection. Ukiyo-e means the floating world. They are intricate woodblock prints, and they began in scenes of pleasure — actors, magic, beautiful women in caught in intimate moments.

And they grew beyond Edo in a unique form of printing, an artform in its own right.

Seeds of the floating world

Ukiyo-e began in a rising middle class. In 1600, the forces of the Shōgun unified Japan, Canning said. Samurai nobility supported the classical arts. The government isolated the country and limited trade and travel, and influential merchants, machishū, lost political power — but internal trade gave them money to spend.

New technologies gave them a new artform to spend it on.

Traditional Japanese artists would often draw firm outlines and drip ink to fill them in. Now, in the new capital city, publishers working with artists and printers developed an intricate form of color printing. Artisans could make copies of an original work, and men who could not afford paintings could hang bright images on their walls.

Ukiyo-e began in the bath house, said Andrew J. Saluti, assistant professor and program coordinator for the Graduate Program in Museum Studies and School of Design at Syracuse University. He curated Ukiyo-e to Shin Hanga for Syracuse in 2013, and it has traveled since then.

Ukiyo-e began in Yoshiwara, a government-sanctioned district in the capital city. For the merchants it meant Geishas playing music, reading or writing poetry, plucking the stringed Shamisen. It meant popular stories, Kabuki and bunraku puppet theater.

For the women in these paintings, it meant culture, competition and prostitution. They were courtesans, Saluti said. Some of the earliest prints were manuals illustrating how to please and be pleased. One of the earliest artists in the show, Kitagawa Utamaro, became known for beautiful women, elongated forms and accentuating faces.

Asai Ryōi, a Buddhist priest and a writer of popular stories of contemporary city life, defined the new artform: “living only for the moment, savouring the moon, the snow, the cherry blossoms and the maple leaves, singing songs, drinking sake and diverting oneself just in floating, unconcerned by the prospect of imminent poverty, buoyant and carefree, like a gourd carried along with the river current: This is what we call ukiyo.”

Ukiyo-e grew beyond its beginnings, Saluti said. Gradually, as the prints became known and successful, the artists began to branch out. By the turn of 19th century, they were painting folklore, legends, demons and Samurai.

A publisher would commission artists for a series of prints on a theme. As restrictions on travel relaxed in the 1830s, artists became guides to travel through Japan and eventually beyond. Their prints mapped trails: Hokusai’s 36 views of Mount Fuji or Hiroshige’s 53 Stations of the Tokaido, a road between Edo and Kyoto by he sea.

“And the world expands,” Saluti said.

Toshiaki Nakazawa, (1864 – 1921), Empress Jingu Invading Korea, c. 1897: According to the Hyde Collection, several Japanese legends tell of the Empress Jingu, who ruled in 201 CE and was absent from Japan for three years while she conquered a promised land, which the country later traditionally identified as Korea. Courtesy of the Hyde Collection and the University of Syracuse

Printmaking as an art

Ukiyo-e caught had a lasting impact, he said, because they were beautiful, and they could reach many people. They were inexpensive, but used skillfully this kind of printing could have subtle and versatile effect.

An artist would work with a print shop, and artisans who cut and inked the wood blocks, and artists could make a living and a name.

“Many masters we focus on, Utamaro, Hokusai, Hiroshige, were artists, painters who rose to prominence because of the prints and the reach they had,” Saluti said.

As a printmaker himself, he marvels at the work this kind of printmaking could create.

“Moku Hanga, Japanese woodcut, is very unique,” he said, “especially when thinking about what a woodcut is, and especially if we compare it to Western woodcuts.”

In the West, etching and lithography grew with the development of presses and moveable type, he said. In the East, they grew with painting.

“The only thing that ties them together is that you’re eliminating negative space, creating a raised surface, a relief,” he said.

In the West a printer would roll over the block with a roller, a dauber saturated with ink, and print in a solid tone, usually in black and white.

“In the East,” he said, “because of the watercolor feel and transparency of the paintings, the printers developed a process, a painterly process, with much finer detail and more delicate transitions for color and line.”

“They create thin black outlines and wash-like impressions by painting inks on the block

with a variation and subtlety you don’t get in relief process in the West.”

Printmaking rode the tide with Ukiyo-e into the late 1800s and returned in the Shin Hanga movement in the early 20th century, and contemporary artists still use it the same way.

“The process has not changed — for three or four centuries,” he said. “Utamaro’s woman looking in a mirror has more than 20 colors, more than 20 impressions.There’s no better way to do that than to have many blocks carved and lined up … to create the image.”

The printers layered colors to create subtle shadings, sometimes painting more than one color on one block. The master printer might paint on inks in a way that makes them mix or set two blocks on top of each other so they blend into layered shades — not only for one print, but over and over again, consistently, to print 200.

Yoshida Hiroshi, Fujiyama. Courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

Japan and the West

In Japan, the Tokugawa government held the country stable for 250 years.

While they limited contact with the West, in Europe, city states were growing into countries; in France, a rising middle class led to revolution in 1789, and Napoleon consolidated the country again in the early 1800s. The artists gathering in Paris lived in a world he had changed.

Under the Shogun, Japan limited trade with the West, until the West forced a way in. In 1853, Matthew Perry, Commodore of the U.S. Navy, sailed gunboats up the coast toward Edo and trained his cannons on shore.

International trade would come with political and economic upheaval and civil war. But it would bring Ukiyo-e across continents.

Though the printing had not changed, the artwork had expanded its subjects, its colors and compositions.

The floating world had become the real world, here and now, as people knew it, Canning said. Images evolved from fantastic landscapes to beautiful places the artists had seen. A legendary empress stands on a cliff’s edge under pine trees. People and umbrellas cross a bridge in the rain.

The artists would condense perspective and intense action onto one plane. They might set an element in the foreground to draw the eye — a branch of plum blossoms, a slope of snow, a paper lantern. Natural shapes stand clear against vivid blocks of color.

Their eye and technique became familiar in the West. Japanese prints reached Paris by the 1870s, and artists collected them. Van Gogh, Degas, Mary Cassatt, James McNeill Whistler all knew them.

Artists in Paris painting outside the sanctioned art world, rejected by academies and salons, found something compelling in Ukiyo-e artists in Edo, Saluti said. Looking at their visions and influences and lives side by side, a contemporary eye might see them overlapping in many ways.

“There’s so much that ties into this,” he said. “The development of photography starts to change the way people view images.”

In Paris, Impressionists and Post Impressionists and Modernists were working in paint-spattered studios with nude models or heading out to sketch fields and harvesters, women in apple orchards and city streets at night. They were painting flattened perspectives, Cubist angles and abstract color.

The Hydes collected ukiyo-e because these artists did, Canning said, and they could see the influence of Japanese artists in the Western artists they knew. They collected paintings and sculpture, drawings and pen-and-ink works on paper, but not many prints.

Many Western artists experimented with etching and lithography, but not always as an art in itself.

“We think of an artist-printer like Rembrandt,” Canning said, who would walk the city with a notebook in his pocket and sketch, but Western printing techniques might not show the artist’s hand as clearly as a drawing would.

But by the time Whistler was making lithographs of London waterfront streets at night, Japanese artists were working more and more closely with their own print form — and showing Western influences in their work.

Yoshida Hiroshi, 1876-1950, created this image of Himeji Castle, 1926. The castle was first built in 1333 and rebuilt between 1601 and 1609. Courtesy of the Hyde Collection and the University of Syracuse

Shin Hanga — tradition re-imagined

In the late 1800s, ukiyo-e was falling out of fashion. But after the Civil War, a new movement would bring wood block printing back in force. The fall of the Shogun and the conflict in 1863 would lead to a major shift, as Japan was becoming both global and industrial, and to debate in the art world about how and artists should allow whether Western influences.

In the early 20th century, between the World Wars, Shin Hanga artists looked to the traditional form of Ukiyo-e with new vigor. Though they worked with artisan printers, Saluti, the well-known Shin Hanga artists in this show made printing and the craftsmanship of the blocks an artform in its own right.

Ukiyo-e and Shin Hanga artist Tsuchiya Kōitsu worked his way up from a print shop, and he had worked to get there.

Kōitsu was a farmer’s son. He came to Tokyo to train at a temple, but with the monks’ support he became an apprentice to a master Ukiyo-e artist, Kobayashi Kiyochiku. He wanted to draw. He wanted to paint.

He was young for an apprentice and made himself useful, doing odd jobs, watching the children, and in time keeping the books. He became a lithographer — until he was told he would die of lung disease if he kept it up.

It took nine years before he began to publish his own work, and he would always be a working artist. He supported a family. He made a living from hanging scrolls for Chinese collectors.

His Asakusa temple scene here shimmers vivid red in the rain. It may show a Western influence in its feeling of depth and space, Canning said, in the one-point perspective Western artists use to give a sense of distance, and in the realism of light and shadow on green leaves at dusk.

Kōitsu’s contemporary, Kawase Hasui, trained as an artist in both Japanese and Western schools and painted in watercolor, plein air, life drawing and oils. He worked closely with the artisans who made his prints. He might take months over the proofs, going over the hue of dyes and the textures that gave the affects of light and shade.

Taking a half-step farther, Yoshida Hiroshi often carved the blocks for his own prints. Saluti is drawn to Hiroshi, among the artists in this show, because his composition and process most closely linked ukiyo-e and shin hanga.

He mulled over Fujiyama — First Light of the Sun, and the landscapes Hiroshi drew as he traveled the world.

“He painted a Grand Canyon print in moku hanga, a beautiful impression,” Saluti said.

And it is here too.

Hiroshi created these scenes as prints from the beginning, Saluti made clear. Shin hanga, like ukiyo-e, might sometimes began with a painting or a watercolor, but even then the artist would paint with the process in mind.

“Many were always meant to be prints,” he said. “The artist would sometimes draw directly on the block.”

They would draw on a sheet of fine paper and then adhere it face down on the cherry wood or hardwood and make it transparent so they could see the drawing, so the printmaker could carve through, and the drawing often doesn’t survive the transfer.

Contemporary artists still use this technique, he said, and printmaking still influences artists today, in Japan and in America — just as Japanese characters, including some in this show, still influence graphic novels and film and video games, Canning said.

That thread from the streets of Edo runs through Paris cafés to the visual culture, pulp / pop culture, gaming and manga and comic books in Japan and in the U.S. today.

The stories behind the thief Hakamadare, and Omatsu, the woman bandit holding her sword, may still be alive and walking.

This article cites information from the Catalogue Raisonné of Tsuchiya Koitsu: Meiji to Shin Hanga, Watercolours to Woodblocks, by Dr. Ross F. Walker and Toshikaza Doi, and Water and shadow: Kawase Hasui and Japanese landscape prints, by Kendall H. Brown, James King, Koyama Shūko, Shimizu Hisao, and Miya Elise Mizuta. It first appeard in the Hill Country Observer in November 2018; my thanks to editor Fred Daley.