A dark stack of peat at sunset may not feel like Van Gogh — not in watercolor. A river at dusk softly undercuts its banks of dark mud with a fringe of long grass. Farmhouses sit low in the background, almost lost against the tree line.

He was 30 when he painted it, in 1883, and he was just beginning to paint. At the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown a week ago, a boy looking at the river said if this were modern days, he would say it was like a scientist doing research on the animals in the water. He has come up beside me in the first room of the “Van Gogh and Nature,” exhibit, and I remember talking with curator-at-large Richard Kendall last spring as he prepared for this show to open — he would have loved that response.

He told me Van Gogh grew up walking in the fields around his house, learning the names of moths and stars, and all his life he felt drawn to the outdoors.

The Clark Art Institute's 'Van Gogh and Nature' came to the Clark Art Institute in 2015.

Not long after he painted the peat stack, on a colder day, he set out for his parents’ house in Nuenen, in the Netherlands, and he headed across country feeling bleak. He writes to his brother, Theo, on Dec. 6, 1883:

“My journey began with a walk of more than six hours — mostly across the heath — to Hoogeveen. On a stormy afternoon with rain, with snow. This walk cheered me up no end, or rather my feelings were so in sympathy with nature that it calmed me down more than anything else.”

What brought him into sympathy with winter slush? He had recently lost his job with a firm of art dealers, and the business of buying and selling art seems cheap and meaningless. He writes in anger and grief that the best artists may be scorned and forgotten and schlock may become popular. His world has changed without warning.

“I thought of you brother, on my long trudge across the heath on that stormy evening … I thought, I am disillusioned, that is — I thought — I have believed in many things that I now know are in a sorry state at bottom — I thought, these eyes of mine, here on this gloomy evening, awake here in the solitude, if there have been tears in them from time to time, why should they not have been wrung from me by such sorrow that it disenchants — yes — and banishes illusions — but at the same time — awakens one?”

It is an unusually long and personal letter. After reams of short notes on pen nibs and paper, the contents of a box of prints and books, an observation on a sister’s trip to relatives, the feeling here beats across the page.

When I saw his early paintings in the Clark show, I had not yet read it. And I wish I had. Kendall told me that all of Van Gogh’s letters exist online, edited and searchable, and I have been reading them this summer in bursts — because I want to get to know the man. Kendall has me convinced that Van Gogh thought long and hard about the natural world, but the show didn’t tell me what he thought.

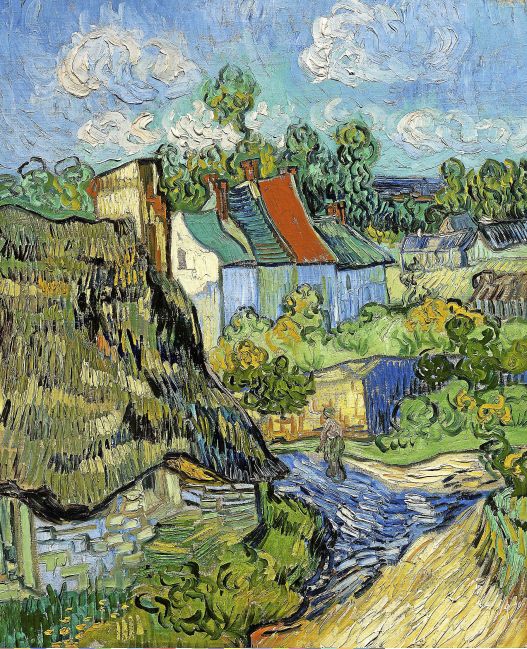

This show moved me strongly, in some places more than others. An avenue of fall poplars caught me, and a farm on a road of vivid summer-parched white sand in the south of France, and rain on a hillside above a town outside Paris … and I could see Van Gogh walking the limestone hills in Arles, identifying bird calls among the clipped trees and terraced olive orchards. But I wanted to know what nature meant to him and what he thought as he walked.

When I stood absorbed in that rare watercolor of the fields at night, I looked at the river and thought of the marshes in my old hometown, the horse shoe crabs and cormorants and periwinkles. That small boy was right, I think, about the part of Van Gogh who saw the life of the river and simply loved knowing what creatures lived there and how they lived.

But I also want to know the part of him that felt comforted by stinging snow. When he painted mowed fields in half-light, a channel of water, clipped grass, did the land feel bare to him, empty, sad or calm?

In his letter, he seems all of them at once. His world shifts — he leaves a trade, begins to paint in earnest, moves to a new home, feels the structure he has lived in collapse around him, feels himself shut outside a world of art dealers and buyers who seem to operate with a set of values alien to him. And maybe the change awakens, as he says, a new sense of strength.

“It’s no reason to lose one’s serenity,” he says, “if one should realize that one might have to lead a life of poverty while one had the skills, the talents, the aptitude with which others grow rich.”