Today I learned that Great Barrington will name its middle school in honor of a native son, a man known around the world for generations. Some people in his hometown have not gotten to know him yet — and some feel a deep connection with him, and feel his ideas beating like a pulse, shaping national debates today.

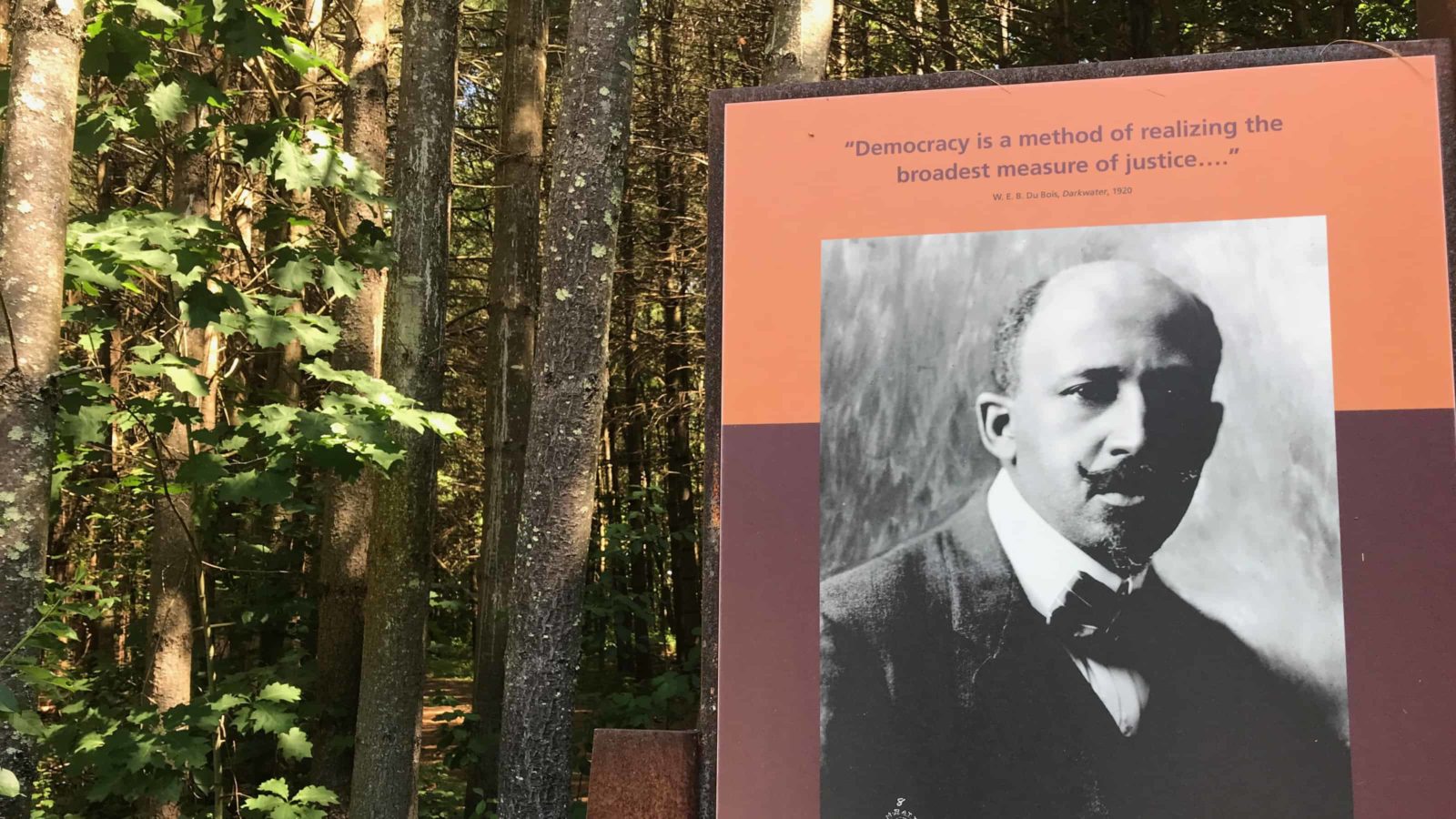

Pine and oak mingle along quiet paths at the National Historic Site of W.E.B. Dubois' boyhood home in Great Barrington.

The path runs cleanly between old white pines. They look more than a hundred years old and five feet thick at the base. It’s a quiet place. The air feels clear in the light. A boy used to sit here by the water when he felt alone or angry. He used to come here to find calm and daydream.

From here he went out to cross oceans. He lived in New York, Berlin, Accra. He traveled the world in his lifetime. He helped to shape ideals of independence in Africa and freedom and democracy in America. Today I imagine him as a young man, as he might have been when he lived in the Berkshires, lying on his back on a pine log, tired after a long day and burning with ideas.

He wanted to be a Black man and an American. He felt those ideas as “two thoughts, two souls, to irreconcileable strivings,” and he imagined intensely a world where they could reconcile. He wanted to use all the powers of his body and mind, and he wanted that freedom passionately. He risked his life for it.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was a boy here. His family lived here for 150 years. For two or three lifetimes, how many generations — as long as the span from the end of the Civil War to today — they held this land and farmed it. He knew its scents and sounds familiarly at night.

He worked for generations for ideas that cut deep today. He wanted his son to live safely. He wanted his people and his wife to have the right to vote, to go to college, fall in love and do good work. He wanted the Housatonic River to flow cleanly. He loved the beauty of spirituals and languages, music and art from all parts of he world.

“We’re still trying to explain that everywhere else in the world, people know Du Bois is from here, and they get excited,” Gwendolyn VanSant, founder of Multicultural Bridge, told me this summer, one afternoon when we were talking about the beauty of his writing and the depth of his influence.

Before I came to the Berkshires, I knew Du Bois as the writer of Souls of Black Folk. I remembered reading it in summer afternoons years ago, and most clearly I remembered the passage when his first son was born. He was a confused young father, holding his child for the first time, and he wrote with awe and love and pain.

“How beautiful he was, with his olive-tinted flesh and dark-gold ringlets, his eyes of mingled blue and brown …”

He was afraid for his son, afraid of what a hostile world would do. And then in the spring when his son was two years old, he was burning with a fever. I didn’t know when I first read those pages that Du Bois looked frantically through those hot Atlanta spring days, and no white doctor would treat a black baby dying of diphtheria.

The baby’s name was Burghardt, after his grandparents. He is buried now in Great Barrington, beside his grandparents, his sister Yolande, and his mother, Nina Gomer Du Bois.

His father wrote that he was buried before the world called his ambition insolence and held his ideals unattainable. As I have lived in the Berkshires, I have begun to get to know Du Bois, in his writing, in conversations with professors and dancers and landscape designers and college students who have found themselves in his words. They talk with me about a brilliant man who wanted the freedom to think with power and intensity.

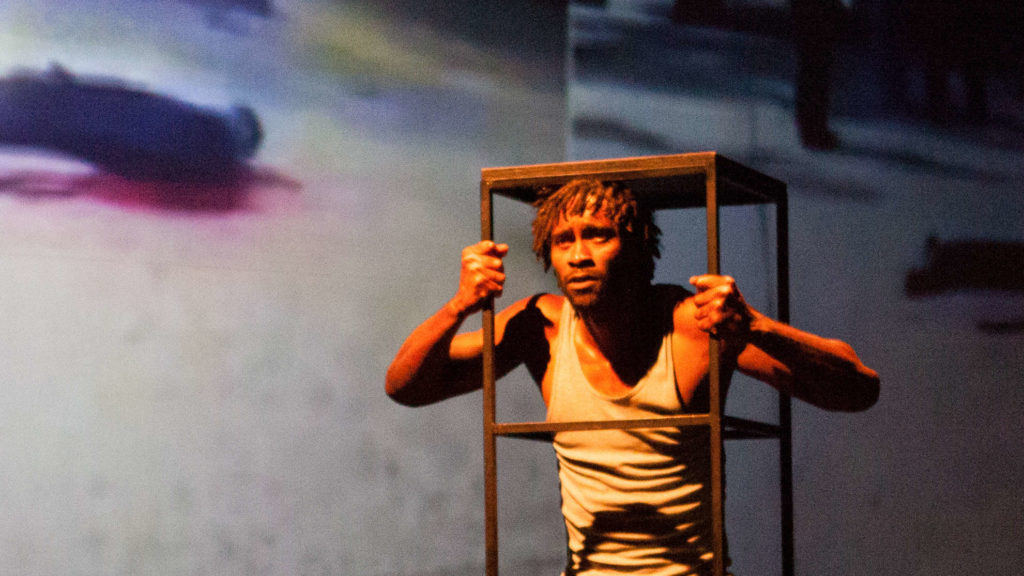

I remember the young actor who talked with me after a performance at Double Edge Theatre a few summers ago. He played Du Bois in his 20s as he was leaving the Berkshires and coming to Fisk University.

He was alight with the natural high of the performance and with the glory of feeling as though he could share this time and place for awhile with a man he admired so deeply. He said had lived with Du Bois’ writing for more than a year as he created the character. He had discovered fiction as well as essays. Living in those stories, he became a man of power and dreams and natural magic. He could make the world new — he could fly.

As a young boy, Du Bois lived here with his grandparents, his mother and brother. He has written about the Burghardts’ house as a comfortable place, living room with a wide fireplace, a kitchen with a flagstone floor, a broad elm tree and the brook.

The Clinton Church Restoration and the Great Barrington Riverwalk told me about the brook one summer day, in an event to honor DuBois’ legacy. That brook became his refuge as a boy. When his father left, his mother and her eldest two sons lived with her parents for two years. When Du Bois was five, she and the boys moved up the road, back to the center of Great Barrington, but surely he must have visited his grandparents often, all through his childhood.

He worked his way through high school and became the first person in his family to graduate. He earned scholarships. He found books and conversation and ideas wherever he could — in literary evenings at the Clinton Church, at town meetings, at the local bookshop where the owner let him borrow books and magazines.

His family lived in the rough working-class neighborhood on Railroad Street, and then for a few years in a quieter apartment near the church. His mother was working to support them, though I’ve read in local histories that she was partly paralyzed from a stroke, and from early on Du Bois was working too. He learned that his classmates would treat him differently, and some school authorities, and the local law.

He describes later, in 1920, “On being black,” the feeling of the relentless reminder of a world that shuts him out: “My white neighbor glares elaborately. I walk softly, lest I disturb him. The children jeer as I pass to work. The women in the streetcar withdraw their skirts or prefer to stand. …”

He found some champions here, but I can see him sitting by the river at dusk, looking for a place where the world will let him be. Ideas, intellectual excitement and the beauty of language can become a refuge of their own.

He became the first black man to earn a PhD from Harvard. He became a professor, an internationally influential writer. He helped to found the NAACP, and he edited its nationally read magazine, the Crisis, for 24 years. And the world heard him. When he died, in August 1963, 250,000 people gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

Today, he inspires composers, choreographers and nationally known architects. And they come to the Berkshires to be close to him.

His ideas infuse conversations here still. Local history, education, urban planning, philosophies of freedom. The RiverWalk read aloud an essay challenging Great Barrington to think about the river. The Housatonic runs behind the main street, hidden behind old houses and worn brick. You can easily drive through town without ever knowing the river is here, even now.

What would happen, Du Bois asked, if the town turned to face it? If that wide flowing water lived at the center of town, and the town looked out on it every morning, how could that change the town’s planning and perspective? It’s a question the environmentalists involved in the PCB cleanup have been wrestling with for a century.

The Housatonic River glimmers in morning light in Great Barrington.

Du Bois came back here almost all his life. He would meet his friend James Weldon Johnson, a nationally acclaimed poet writing God’s Trombones in a cabin behind his summer house. Randy Weinstein told me about their friendship, one afternoon when we were talking in his book shop beside the cemetery where the Burghardts are buried together. Johnson too loved the rhythms of storytelling and spirituals and sermons, the richness of oral traditions.

Du Bois wrote about the depth of those traditions. Decades before James Baldwin, before the Harlem Renaissance, before Langston Hughes wrote jazz poetry in the Crisis and Sterling A. Brown graduated from Williams to write poems with the voices of the rural South, Du Bois opened every chapter in Souls of Black Folk with music.

In the Dusk of Dawn he remembers his Great Grandmother, Violet, singing an African song to her children, as his grandmother and his mother sang it to theirs. Do bana coba, gene me, gene mel Do bana coba, gene me, gene mel Ben d’ nuli, nuli, nuli, nuli, ben d’ le … “And so two hundred years it has traveled down to us, and we sing it to our children, knowing as little as our fathers what its words may mean, but knowing well the meaning of its music.”

He wrote with the same respect when he first came to Africa. It was new to him and unfamiliar, he wrote in Dusk of Dawn, and he felt the hundreds of years of his American blood meet the land where people in his family with names he didn’t know had lived six generations before.

“Christmas Eve, and Africa is singing in Monrovia. They are Krus and Fanti- men, women and children, and all the night they march and sing. The music was once the music of mission revival hymns. But it is that music now transformed and the silly words hidden in an unknown tongue-liquid and sonorous. It is tricked out and expounded with cadence and turn. And this is that same rhythm I heard first in Tennessee forty years ago: the air is raised and carried by men’s strong voices, while floating above in obbligato come the high mellow voices of women — it is the ancient African art of part singing, so curiously and insistently different.

“So they come, gay appareled, lit by transparency. They enter the gate and flow over the high steps and sing and sing and sing. They saunter round the house, pick flowers, drink water and sing and sing and sing. The warm dark heat of the night steams up to meet the moon. And the night is song.”

And so that day by the River Walk musicians played compositions to honor him. Long notes on the saxophone, and the rhythm underneath like the river in the rain. The drum playing with the wind in the trees.