In the days after the election, Safiya Sinclair sat in a quiet study and wrote new poems. She was walking around scared and depressed, she said. The feeling is strong, and it is also familiar.

“Some of America is waking up to what is a commonplace reality for many people,” she said, “feeling like you’re in exile in a place that is supposed to be your home. What makes it terrifying is that now it is mandated into law at the highest level of government.”

In past the year, as her first book of poetry has won awards for her tough and supple invocation of life in the Caribbean islands, she has come as poet in residence to the Amy Clampitt House in Lenox. She has been writing a memoir here about growing up in Jamaica in a conservative Rastafarian household. And this week she has turned to poetry to channel fear and pain into writing.

“It’s a good way to make sense of things that happen in the world,” she said.

She has held to it since her high school years.

“I had always had a longing, curious mind,” she said.

When she graduated high school at 15, she had no means of going to college. She submitted a poem to a national newspaper, and a Trinidadian she names as the Old Poet reached out to her and mentored her.

She would beg visiting family to bring her books, she said. She memorized Keats and Wallace Stevens and Sylvia Plath. But the few books she could get were Western, European, and almost all written by men.

“It was fantastic poetry, but I still had to make my own education,” she said.

And she found the same in the U.S., when she came to Bennington College on a scholarship. She found herself one of a few black students there, and at the University of Virginia, where she earned her MFA. At Bennington, she said, her classes taught only one black writer in her years there.

At UVA she met a poet she loves, Rita Dove, who has become a mentor to her, and Sinclair has found writers on her own — Audre Lourd, Lucille Clifton, James Baldwin — who have given her strength and a sense of community, of not being alone. But she has found fewer Caribbean writers, she said, and even fewer of her own generation.

“A lot of extraordinary circumstances have to happen, by chance or not, for a Caribbean writer to come to literature as a thing you decide to do against the odds, and then to thrive at it,” she said, “a lot of circumstances outside our control.”

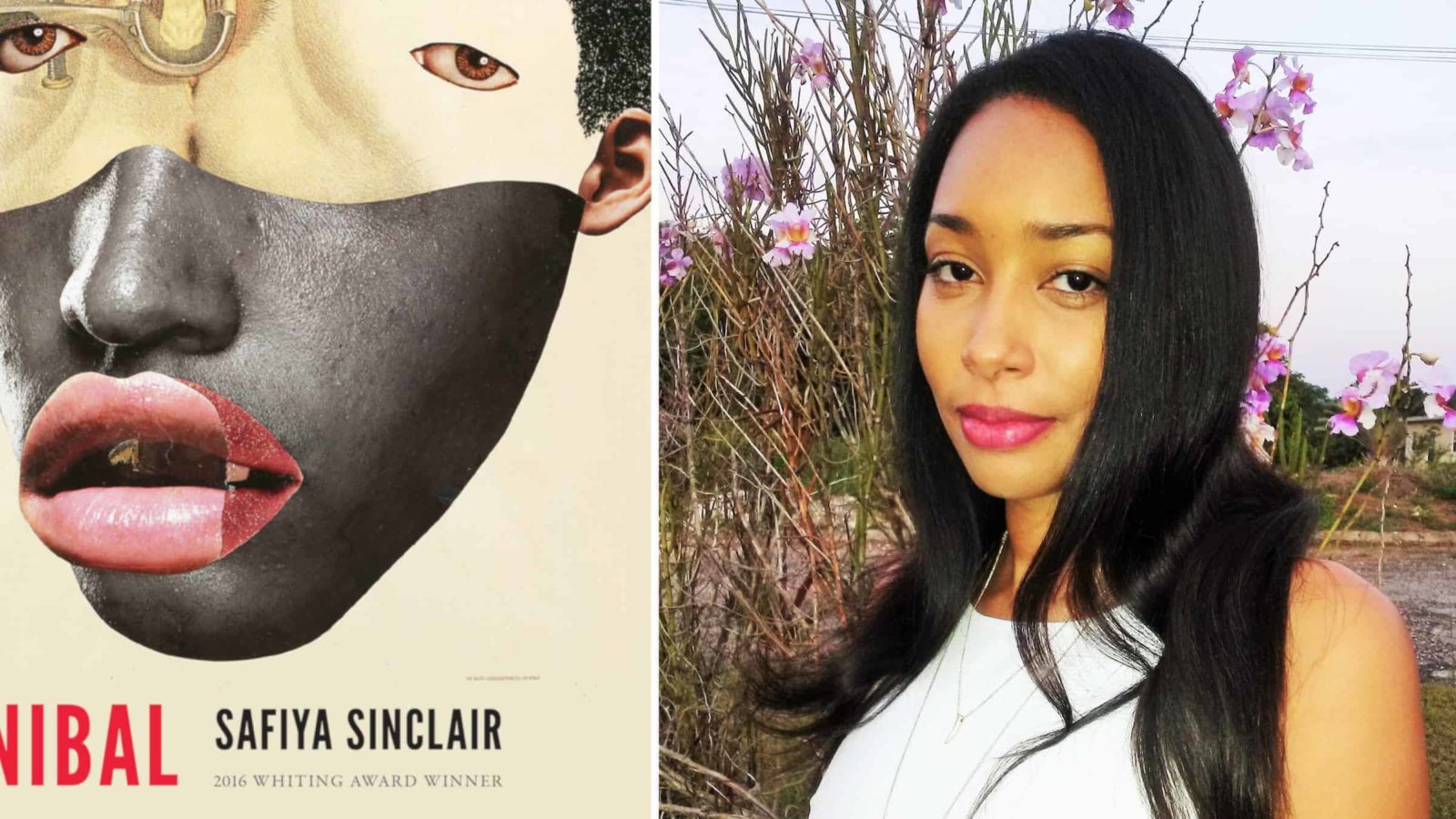

So she speaks from a perspective she has rarely seen in print, as she is now. Sinclair is a doctoral fellow at the University of Southern California, and her first book, “Cannibal,” published in 2016, has won the Whiting Award and the Prairie Schooner Book Prize in poetry.

She has chosen the title carefully — reclaiming it. She explains in the book: “The word ‘cannibal,’ the English variant of the Spanish word canibal, comes from the word caribal, a reference to the native Carib people in the West Indies.”

“I discovered this root myself,” she said. This kind of language “still shapes the way we say and think about things in ways we don’t understand. I am a Caribbean woman, but ‘Caribbean’ itself is rooted in this word.”

When Columbus fought to subdue the people of the islands, she said, the people who resisted he named Caribes, and the ones who were more welcoming he named Tainos.

So she has turned the word on its head to find beauty and independence in it.

“In the tropics nothing grows politely,” she said. “It’s part of our culture and our roots. If resisting white supremacy and post-Colonial evil makes me caribes, then yes, I claim that.”

‘In the tropics nothing grows politely. It’s part of our culture and our roots. If resisting white supremacy and post-Colonial evil makes me caribes, then yes, I claim that.’ — Safiya Sinclair

She writes the life of the islands in visceral images — conch shells and coral, lizards and jackfruit, Jumbie birds and poinciana trees, the hard wear of physical labor, the wreck left by Colonial violence and the slave trade, and the rhythms of Jamaican patois.

Patois is blended from West African languages, especially from the Akan people of Ghana, and English. And it has become deeply important to her.

“A lot of people in Jamaica think if you speak in Patois you’re uncultured, uneducated, lower class,” she said. “Growing up, I didn’t speak it. I found it shameful to do so. After coming to America and interacting with people outside of my home, it made me consider my Jamaican self more closely. It’s something I don’t want to lose, and something I want to celebrate.”

She incorporates it in her poetry in many ways, knowing that some readers may not have the context for it. Some have even tried to stop her from using it. In an undergraduate workshop, she has had a story returned to her with comments in pen, telling her to write it “in English”

“It was an important point,” she said. “Instead of turning me against patois, I said no, my language isn’t going to be colonized or watered down, demeaned, diminished. I turned toward it as a source of strength.”

‘… I said no, my language isn’t going to be colonized or watered down, demeaned, diminished. I turned toward it as a source of strength.’ — Safiya Sinclair

Her brazen, forceful self is her patois self, she said. She honors and shares the beauty of it in the structure of her lines, in their sound and meter. In the poems in “Cannibal,” she is uses spacing, makes verbs out of nouns, and blends in words of patois and Jamaican folklore.

“Kamau Balthwaite says ‘the hurricane doesn’t roar in pentameters,” she said. “… because of where we’re born, our poetry has to reflect our natural world, with all its violence and all its beauty. I come back to the page to reflect and write down the music that I’m hearing.”

She reflects that tempo in a poem like “Pocomania.” Pocomania is a Jamaican folk religion, she said, with its own dancing and singing like entranced chanting. She has invoked the rhythm of a ritual — father, father, father echoing in her lines.

In “Dreaming in Foreign,” she invokes Jah, a Rastafarian deity, and the lines feel to her like a Reggae song — her father is a Reggae musician.

“When I say it out loud,” she said, “it is very like a spell.”

How time holds me under

a shadow I cannot name, the bush-music and its sweet

bangarang. Do not wake me. …

‘How time holds me under

a shadow I cannot name, the bush-music and its sweet

bangarang. Do not wake me. …’ — Safiya Sinclair

She writes here in the voice of Caliban, the man born on the island in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. She recalled him in Shakespeare’s play, being enchanted by the island, the sounds of the sea and the night woods, and not wanting to wake up.

In the last poem in “Cannibal,” Caliban speaks the words spoken about him in the play, the ugly insults. He claims and masters them.

I abjure you

and wear your gabble like a diadem

this flecked crown of dictions

this bioluminescence …

In the title of the poem, “Crania Americana,” Sinclair said, she directly confronts the pseudo-science of measuring the skulls of human beings to measure their minds. Caliban is measuring the kind of mind that would distort what it sees so brutally.

“I’m trying to give Caliban a voice,” she said. “He is a reflection of the Caribbean soul. Being at home but not at home. Speaking a language that is not quite yours while thinking in another language and moving your body in another language.”

He helps her to understand and express a sense of exile she has felt in many ways — in leaving Jamaica, in being black in America, in being a woman and growing up in a strict household where women’s bodies were seen as shameful.

“I have had to work to get to a point where I am confident in this body,” she said. “This is my body, and this continues to be relevant. I’m taking this body seen as scary or weak or vulnerable and making it a place of power.”

She writes for herself and for her family and to give voice to the people struggling in the country where she was born.

“I wanted to give voice to women like my mother,” she said. “Their labor has lifted me up. I wanted to give tribute to them while thinking of the macabre history of the Caribbean that has led us to this place.”

And so she hopes to make something that will go on and look back to the people who have led her to be here, because they have supported her, or because they have survived against the odds so that she can be alive and writing here today.

“There’s something so potent in the poetic form,” she said, “distilling, packed in this small space. This thing you built will outlive you and last. This voice will go on beyond me, and has. I’m lucky to see that, and how powerful that can be.”

This story originally ran in the Berkshire Eagle — my thanks to features editor Lindsey Hollenbaugh. In the photo at the top, awardwinning poet Safiya Sinclair has published her first collection of poetry in 2016. Photo courtesy of Safiya Sinclair