Today students read graphic novels and James Baldwin. They follow the ways he weaves music into his novels and essays, in the names of songs and the rhythms of gospel and blues in his words. And then they write their own songs.

They dance to marimba and jembe drums. They study Swahili stone palaces on the East coast of Africa, and timber mosques in the Sahel, and filmmakers in Haiti … under the guideance of more than a dozen faculty, and colleagues in music, dance, theater and more.

Africana Studies at Williams College has evolved as an interdisciplinary field of study for more than 50 years. It emerged in the 1960s, in the Freedom Movements, says Williams associate professor of Africana Studies LeRhonda Manigault-Bryant, and it has grown to encompass the vast experiences of the people of Africa and the African Diaspora around the world.

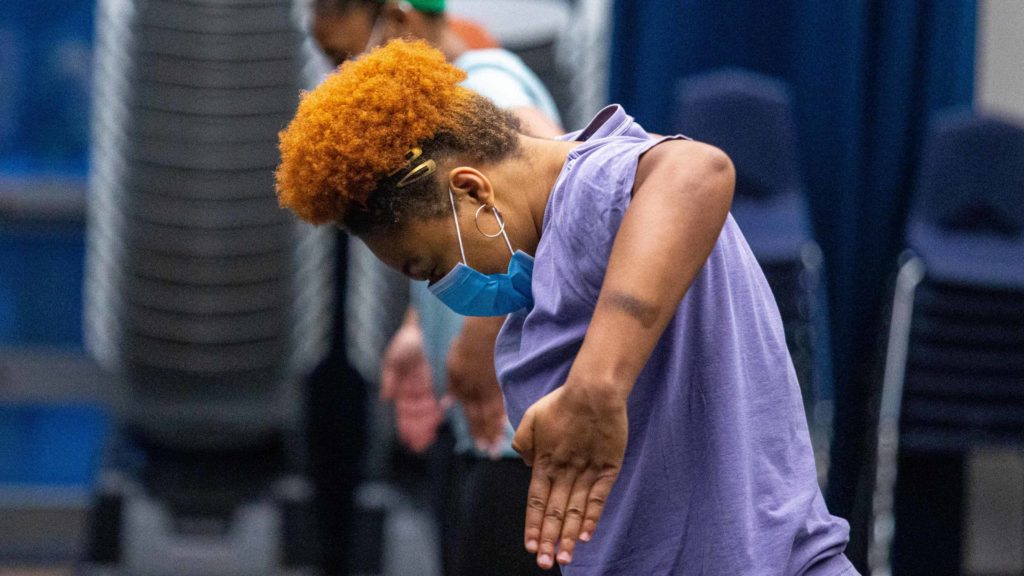

Students rehearse with Sankofa, the college Step team. Press photo courtesy of Williams College.

Students set change in motion

The program began, in many ways, in the spring of 1969 — on the morning a group of Williams students walked into Hopkins Hall and called on the college to hear them. They were young black men, she says — the college would not admit women until 1970 — and they wanted support from the college community.

They wanted room to think clearly about the work they want to do and who they want to be, Manigault-Bryant says, as any student wants today.

She has looked into that time, as she has curated an audio and visual exhibit from the college’s collections at Sawyer and Chapin Library. As she traced students and professors and alums, she has looked into visions of the future and movements in the college and in the country since the program began.

Renni Magee and Cody Hayman appear in Alien/Nation at Williamstown Theatre Festival — a play based on the Williams College student occupation of Hopkins Hall in 1969. Press photo courtesy of the theater.

They are fluid movements, she says, and they are often cyclical. The challenges those students faced in 1969 matter strongly today. They were saying, as the Black Student Union is saying in its own programming 50 years later: We belong where we are.

“That’s so much of what I get a sense of,” she says, “from Black Williams speaking through the archives. We belong. We are and we belong. And this can be a space for doing that work.”

History in the making

One step in the work began 4:30 a.m. on April 5, 1969. Thirty four members of the Afro-American Students Union walked quietly into Hopkins Hall, the administration building at Williams, led by Preston Washington ’70. They would stay there until 1 a.m., April 8, peacefully and steadily negotiating with the college, and the agreements they reached are still growing community and noticeable change today.

Those three days came out of a year of growing frustration and determination, Manigault-Bryant says.

Performers invoke 1960s protests at Williams College in Alien/Nation at Williamstown Theatre Festival. Press photo courtesy of the theater.

“Like any protest,” she says, “there were a large community of people who were participating, always a building up, a bubbling up, to these moments. Students here from 1968 to 1973 led a revolution on campus.”

It had been a long, hard year in the U.S. On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, and in the months that followed, protests called for change on campuses across the country — Cornell, Yale, Harvard, Dartmouth, Oberlin and more.

At Williams, students said, being Black meant living under constant pressures — a daily experience of condescension, superiority and unthinking exclusion. Some were blatant, some more subtle but no easier to deal with.

“Being at Williams is like being in a social laboratory,” Dick Jefferson ’70 told the Record, the college newspaper, in 1969. “It’s like being under a microscope.”

Williams was entirely male then, and very largely white. In the 1920s and 1930s, the college might have one or two Black students in each year, no more than five or six on campus at any one time, and in the 1960s they had about 40 out of 1000 students.

Jefferson’s classmate, Bill Coleman, said “Black guys here feel like mannequins on display.”

‘Being at Williams is like being in a social laboratory. It’s like being under a microscope.’ — Dick Jefferson ’70

He and Jefferson described white professors constantly asking them what Black people think, and white classmates ignoring them, or asking ignorant questions, knowing nothing about their culture or experiences or history.

“I was feeling that I was brought here for your education, not mine,” Jefferson said.

Neville Hughes ’69 used a musical analogy, the Record recalls: “All your life you hear nothing but soul music, and suddenly everyone up here digs the Beatles, and when white guys listen to your music, they act like they’re doing you a favor.”

Jaime Lee Rodney and Debbie Warnock recall a moment Williams students and staff, as he dances in Alien/Nation at Williamstown Theatre Festival. Press photo courtesy of the theater.

In this environment, Washington took on leadership of what was then the Williams Afro-American Society and is now the Black Student Union. He was a 20-year-old political science major from East Harlem, the Record said. And he led the group in opening conversations with faculty, fraternities (still powerful on campus then) and the administration.

He had a wife and a child on the way — and he would graduate in a year with an open letter to his infant son. As he wrote in his open letter to the administration, he wanted to set changes in motion while he had time and could take part.

In March, the society presented the college with a set of specific demands. They felt, Washington wrote, that they were seeing too little change, too slowly. They imagined a college where they could live comfortably and learn freely, share with excitement in a broad and diverse intellectual and cultural life and build skills to bring home to their communities.

They wanted to be involved in the conversation about creating the Afro-American studies, which would to go into effect in September 1969, and they wanted to expand the program into departments not yet involved — art, music, psychology, religion.

Performers invoke 1960s protests at Williams College in Alien/Nation at Williamstown Theatre Festival. Press photo courtesy of the theater.

They wanted support for the Williams Afro-American Society and a wider perspective in performances and events on campus. They had visions for a cultural center on campus, a leadership conference, connections with Black intellectuals, creative minds and activists, local community.

They wanted the college to bring in at least 25 Black students in each class of 250, and housing where Black students could live together. On the day they occupied the building, they found support on campus.

“Hundreds of students rallied,” Manigault-Bryant says, “trying to get the institution to move.”

The provost at the time, Stephen Lewis, talked with them as a representative from the college president. In the Record, he spoke of their commitment, their respect and the substantive issues they focused on.

Maxine Lyle, dancer and choreographer, co-founder of Sankofa, and Williams College '00, returns to Williams as an artist in residence. Press photo courtesy of the college.

“They are not willing to compromise their fundamental beliefs,” he said, “and it’s good to deal wth people like that.”

The students reached an agreement with him in the small hours of the morning. Before they walked outside, they cleaned the building and left handwritten notes for the people who worked there: ‘Thank you for the use of your desk. Nothing was disturbed …’

Explorations in a new and growing field

Some of the seeds took root within the year. The Africana Studies program opened in the fall of 1969, and 26 Black students entered in that year for the class of 1973. And 44 Black students would graduate in 1975, in the first class to have black women among the students.

Others have taken generations to germinate. The Davis Center, the a multicultural center, was established 20 years later, in 1989 — after another student protest, on Friday, April 22, 1988, when students belonging to the student group CARE (Coalition Against Racist Education) took over Jenness House, the temporary home of the Dean’s Office.

The concerns students raised in 1969 — some of the same concerns were raised in 1988, and again in 2011, Manigault-Bryant says.

“We’re looking at the ways these things cycle through,” she says. “… If we forget history, we’re bound to repeat it.”

Students rehearse with Sankofa, the college Step team. Press photo courtesy of Williams College.

In her exhibit, she shows a visual timeline from the college’s earliest Black alumni to students today, honoring the rich creativity in faculty and student work.

She honors professors and the courses they have offered, ensembles and performances. Choreographer Maxine Lyle, by a group of students including who returned as an artist in residence in 2020-2021. Kusika, the African dance ensemble, has grown with energy, founded by 1986 by professor of music Ernest Brown, percussionist and composer Gary Sojkowski, and director of dance Sandra Burton.

They often perform to live music from the Zambezi Marimba Band, an ensemble Brown founded in 1992. Students perform on brass, woodwinds and percussion — marimbas from Zimbabwe, broad wooden instruments with their clear tones, and Ghanaian marimbas, gyil, with a pentatonic tuning.

“Professor Ernest Brown has such a long and deep history,” Manigault-Bryant says. “He came in 1988 and retired in 2011, and his work as an ethnomusicologist, the creation of the marimbas for the Zambezi Marimba Band — he co-founded Kusika — all these things continue to have life. Kusika and Zambezi are part of the long-standing work Black Williams has done and continues to do, and Africana studies is part of that — I’m excited (to celebrate it.)”

One group of students created a Wild Seed meal riffing on Octavia Butler and celebrating her novels — speculative and science fiction, set when humanity is surviving on the edge of chaos. A young woman fights for her chosen family in a collapsing world. Beings travel between planets. The students set out three courses inspired by her ideas, with bacalao (cod fish in a Panamanian recipe), a collard green salad with blackberries and flax seeds, and a dessert made with figs and wildflower honey.

“Considering where we are, we have a very robust curriculum,” Manigault-Bryant says. “It’s a testament to the benefit of time, being able to stand and withstand the test of time, and that’s a very important thing. I am very excited about where we are — which isn’t to say there isn’t work to be done, because there’s always work to be done.”

That work has continued to expand among students and faculty, alums and visiting artists in activism and intellectual curiosity. and celebrations in music and art.

Awrdwinning South African choreographer Dada Masilo performs the title role in her re-imagining of Giselle in the '62 Center at Williams College.

Honoring 50 years of community

As Manigault-Bryant was researching her exhibit, Horace Ballard, then deputy director at WCMA, was curating an exhibit of James Van Der Zee’s photographs from the Harlem Renaissance. South African choreographer Dada Masilo opened the ’62 Center’s season with her internationally awardwinning performance of Giselle, re-imagined with new music.

And in spring, on the anniversary of the protest, the Africana Studies Department held a 50th year reunion and celebration, April 4 to 7, 2019, with students, alumni, staff, and faculty and distinguished guests.

The department commemorated dean Stephen Sneed, husband of MCLA professor of history emerita Frances Jones Sneed, and they welcomed Black alums across the generations. Making room felt important, as they planned the course of that weekend, Manigault-Bryant says. She wanted to make room for many people and many stories. She hoped many alums would come back.

“One of the things we really really hope,” she says, “especially for black students — black students have a complicated relationship with Williams, as a predominately white school in the Berkshire hills, and we want people to come who have had good experiences, or problematic or tough ones, to acknowledge that this is part of what it has meant and to get accounts or their experiences. Will you tell us so we can document it?”

A singer performs on Stony Ledge overlooking Mount Greylock on Mountain Day at Williams College. Students celebrate a fall day with music and outdoor activities.

She wants to invite people in the Black alumni network to come to this space, to gather and to talk through and share these histories.

“I’m a black faculty member,” she says, “and challenges the students have are challenges I too know well.”

“One of the stories that comes out so clearly in the archives is that students think they encounter the rough edges of Williams — or is it the center? Part of the exhibit is to remind current and former students that they’re not alone. Everyone has their own path and narrative, but so many (themes) are the same.”

She went to Duke University, and she remembers … this year they lost Brenda Armstrong, one of the first black students there.

“The experience she had is not the experience I had,” she says, “not by a long shot, and yet what she experienced as claiming space in a predominately white space is challenging.”

Students perform wtih Kusika, the student African American dance ensemble. Press photo courtesy of Williams College.

Imagining the future

As she looks back, Manigault-Bryant looks as intently ahead.

“My wish for Africana studies, and this is just me, is wanting to wanting there to always be room, and pretty good room, to actually do the work that requires us to think critically about race and intersections of difference in thoughtful and robust ways, not just driven by politics, not just responding. (This is part of) what it means to be a liberal arts institution and educational institution. We would be remiss if we did not help our students, all of our students, grapple with the elements of race.

“It is one thing Black alums wish for Black students coming here, that they have room — more room, more space, faculty. It’s one of the most amazing things it means to be a professor at Williams. Not only are my students so bright, so gifted — I really get to know them.

“There are only so many ways that can be cultivated responsibly, and I want all of them to have the best experiences possible, and to do the work, to do the critical thinking about the work they want to do and who they are. And I want to disrupt the idea that who you are and the work you do are separate.”

The department gives an Ernest Brown arts award now, every year, to students doing work we know he would want to continue.

‘Not only are my students so bright, so gifted — I really get to know them.’ — Professor LeRhonda Manigault-Bryant

“It’s amazing to think of the ways he continues to live in our department. We shifted from a department who hired people in other departments who offered classes — now we’re hired into Africana studies.”

Looking at the program today, she sees a robust curriculum and a long reach. She considers its growing presence beyond the college. Some of the leading voices in her field have local ties. W.E.B. Du Bois, the voice of Souls of Black Folk, was born in the Berkshires — internationally known writer and activist, co-founder of the NAACP.

Among 20th century poets, Williams students in the program will study Claudia Rankine,

nationally recognized writer of six collections, a MacArthur Fellow and Williams alum.

“We have audio from Sterling A. Brown, who came back in his 70s, and they have those recordings digitized,” Bryant says. “That’s something I look forward to people encountering. We have an embarrassment of riches.”

Williams college students performed in a New Orleans-Style Jazz winter study class in winter 2019.

Brown, a Harlem Renaissance poet, has become one of America’s most influential poets and scholars. As a professor at Howard University, he taught and studied Black American folklore and literature for 40 years, and he brought into his own work the rhythms of real speech and the music of ballads, work songs, spirituals and blues.

He was also a Williams alum. Fifty years after that morning on Chapin Hall steps, Brown’s family gave the college his archive — his collections of books, manuscripts and record albums documenting his life and work, with manuscripts, photographs and sound recordings.

In the past year, the college has Jessica C. Neal has come to campus as the Sterling A. Brown archivist. She comes to organize and research his lifetime of documents, as former College Archivist at Hampshire College, Harlem Renaissance scholar and oral historian focusing on the ethics of documentation that focus on Black-led social movements, Black literary history and culture, art and liberation.

And she is planning a symposium in his honor in fall 2022 — a hundred years after he graduated.

When he returned in 1973, he spoke to what he learned at Williams,‘how to read, how to teach, how to think,’ and to what he could not learn at a then segregated Williams, ‘the strength, fortitude, humour and tragedy of my people.’

Bryant returns to the depth in her students’ words today — We belong where we are.

“It’s powerful statement,” she says, “and there’s no better time to offer that message and to embrace it.”