On a sunny morning, a group of young people stood in the meadow below an open ridge, reading a poem that Theresa (Miller) Beaudieu, a member of the Stockbridge Munsee Community Band of the Mohicans, wrote and set here in 1997.

‘… Your feet once stood here

imprinting the earth

where I stand

in moccasins I will never see

dancing

bending in this same sun

to a song I will never hear. …’

Stephanie Wright was talking with the group about the Stockbridge-Munsee, the Mohican people who lived for hundreds of years in this river valley. They live now in Wisconsin, and they return here often, and they have written and preserved a story on this ground.

“They were very good at telling stories,” Wright said with warm admiration. “That’s how they passed on their culture and their traditions.”

She was leading a lesson in storytelling. She asked the group to tell their own stories, and they were eager to share.

“I think Leila told us her story for five minutes,” she said. “She wanted her story told. We made books to tell our stories. We asked permission from the rocks and the trees before we wrote.”

Wright is a teacher with Multicultural Bridge, their Community Engagement Coordinator and lead educator, and a permanent substitute teacher in the the Southern Berkshire Regional School District, and the young people around her that morning were learning in a program Bridge calls their Happiness toolbox. Bridge has run the program for 10 years now, and it has transformed to navigate this challenging year.

As Berkshire schools are re-forming with safety guidelines around Covid-19, students are learning at home, or partly at home, or at school a few days a week, with masks and distancing — and Gwendolyn VanSant, director of Bridge, and Wright consider the ways their teaching has adapted.

They shape their programs around positive psychology, they said, building confidence and growth, strengths that feel even more important to them now, when many kids and teens are feeling isolated.

On that late summer morning they met with a small group outdoors at the Thomas and Palmer brook reserve, more than 200 acres on the southwestern slope of Threemile Hill ridge, between Beartown State Forest and Monument Mountain.

Berkshire Natural Resources Council keeps this land in Great Barrington on the way to Butternut. VanSant lives half a mile away, and she has gotten to know those trails since Covid-19.

“It’s a magical space,” she said.

In the meadow around the Stockbridge-Munsee dedication, Wright was teaching Berkshire history from many perspectives. She and VanSant and the Bridge students made books with Great Barrington artist Suzy Banks Baum. They also visited the historic studio at Chesterwood, Wright said, and talked about Abraham Lincoln from a Civil Rights perspective and a historical perspective.

They talked about James Van Der Zee, the photographer born in Lenox who became nationally known for his portraits from the Harlem Renaissance and beyond.

“We had a lot of storytelling,” Wright said. “Everyone felt valued. And the youth taught about what they’re passionate about.”

Teaching in a pandemic summer

“I got a different perspective on the students this year than in any other year,” Wright said. “Even though some felt hesitancy on the new digital platform, they were eager to get on in the morning and do what we were saying and listening intently. When Carmen had them get up and stretch, they were doing everything we were saying.

“In the public classes teachers were saying their children aren’t engaging on the screen.”

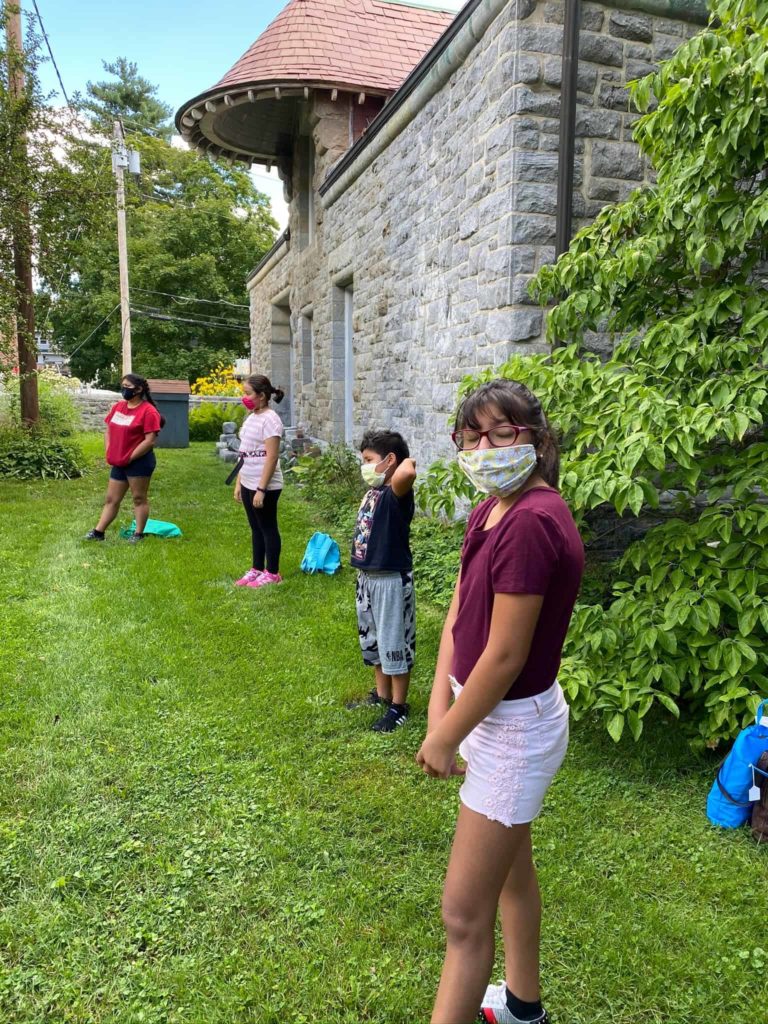

Bridge has created some activities the kids could do together in person, some they could do together online, and some they could do on their own time. When they met physically, they would bring groups of 10 to 12 kids together, VanSant said, so with the staff and hosts they had fewer than 25 people.

“They were glad to be around their friends and be safe,” she said. “During it we had masks on and a lot of ‘put your arms out, put your wings out’ to keep a distance.”

Their instructors are teachers and scholars and local artists and youth who have grown up with Bridge programs.

“We have academics with Ph.Ds,” VanSant said, “and we have 12-year-olds teaching their native languages.”

Damari Taylor, a teenage youth leader, talked about the traditions in braiding hair.

“She taught all the kids to love their hair,” VanSant said. “She taught head massaging and braiding — she taught them all a special braid, and they all were braiding their hair.”

The Youth leaders bring their own enthusiasm, she and Wright agreed. They encourage and excite the younger students and become role models for them.

“The children were so engaged,” Wright said, “and they wanted to do what the instructors said.”

She considered the challenges in teaching on Zoom in a virtual classroom.

“If you’re stoic and not engaging, monotone, you’ll lose your students,” she said. “They’re not going to come the next day. We were getting in touch with children themselves and their feelings. How they were coming to the classroom. Sometimes (they were) sad.”

She held their attention, telling them Berkshire stories they often had not heard, acting out Elizabeth Freeman getting hit with a hot poker. Freeman came to the Berkshires enslaved, in the house of Colonel John Ashley, and when the newly formed Commonwealth adopted its constitution, she sued for her freedom, took her case to the the state courts and won. In her days enslaved, Col. Ashley’s wife is said to have struck her with burning hot iron, and Freeman stood her ground.

The students respected her courage, Wright said. And when the group talked about James Van Der Zee, the children all wanted to take photographs. History and artwork and the outdoors came together, and confidence, and curiosity.

Learning history from many voices

The group went to Chesterwood together.

“None of the kids had been there,” VanSant said, “and they loved it.”

She remembered Lincoln in the background, that standing monument.

“It was a blazing hot day, and kids were on the trails,” she said. “They went on the hike and had a beautiful time exploring the sculpture.”

Some of them have lived here all their lives and had never been there before, Wright said. Sharing the new experience with friends and adults they trust, they feel safe in a group where they can express what they are thinking openly. And now they are back in school, they will be able to tell people what it’s like.

“Because we were in our family, our Bridge family, it didn’t feel intimidating,” VanSant said. “I’ve been working with arts organizations on audience engagement, how you welcome different people.”

She talked with her group about Daniel Chester French and Abraham Lincoln.

“I got questioned because I was teaching the old dead white guys,” she said, laughing. The teenagers asked her why she was telling those stories, while Wright talked with them in her programs about Elizabeth Freeman and James Van Der Zee.

“And I said it’s good to learn about Lincoln from a black woman,” VanSant said.

She encouraged them to ask questions.

“Learn what you learn in your history books,” she said, “and look up more facts and think about what it was like (for more people, in that time).”

She sent them history books to do more research.

“People told me afterward I was zesty,” she said, “and I said, it’s the kids. If you fill someone else, it will fill you.”

At Chesterwood they explored the woods and fields. They saw the beehives there and talked about bee-keeping. Some got over their fright of bees, she said. Some students said their fear evaporated as they understood the bees — that bees don’t try to sting on purpose, that the females do all the work.

Later VanSant brought them to Gideon’s Garden and Woven Roots Farm in Great Barrington, sites where they could see the fields where the food is grown and the people growing and harvesting it.

The group talked about mindfulness and resilience, she said. Covid-19 has brought some opportunities with its challenges. This summer, the program has expanded, working with artists and organizations beyond the Berkshires. She met and brought in a company of hospital clowns who focus on diversity and representation, inclusion, race and empowerment.

“The kids help them problem-solve and have fun,” she said, “and we bring them into our culture.”

They talked with artists in Atlanta, California, Boston, who speak to the kids in Cantonese and Spanish and English. The kids had props too, clown noses and glasses, and a deck of cards with character strengths: kindness, bravery. They talk about those strengths throughout the program, VanSant said. They will sit in a circle, and the kids will choose a card to build on, that day. And they will support each other as they show strengths: “I see you being kind.”

The students respond, Wright said. They pay attention and get involved in ways she has rarely seen in a classroom.

“As a public school teacher, I don’t remember that,” she said. “For the whole two weeks we weren’t saying stop that, don’t do that, sit down.”

The students were looking closely and listening actively, and the teachers and leaders were talking with their students about how to practice both skills.

“They were following what we were doing,” she said, “and they were liking it. They didn’t want to leave — they wanted to keep going. We put curiosity and kindness first. We put the two together. And I think they went up to it, 100 percent.”

They were eager, she said. They showed a zest for learning.

“Those children were in their homes,” she said, “so they knew their parents were there. … When they go into public buildings, brick and mortar, it may make a difference. You have rules and regulations at school. You have to walk this way and sit this way. … We have allowed those children to be their own unique and authentic selves.”

Recognizing resources and challenges

For some families, the parents weren’t home during the day, VanSant said.

“Jonathan was 8, and he was with his grandparents. He was and calling them and asking where the zoom link was.”

VanSant is keenly aware that families have different resources and constraints.

“People need to feel heard and understood,” she said. “We made sure everyone had (what they needed). We had some people who said ‘I want my kids to do it, but we’re on our computers for work.’ ”

Too often people can feel excluded from a program if it asks for materials or resources they don’t have, Wright said.

“If you don’t have the book or the pencil or the sewing kit, they say, oh well,” she said. “Happiness Toolbox turns that 180 degrees,” and the families in the program feel respected. “They feel that love and kindness, and they express it back.”

Bridge sent each family a tote bag with all of the materials students would need for all of the projects, and they set up several ways to be involved.

For each day, the kids could watch a video the night before, to see what they would be talking about in the next session. Bridge led interactive activities online, and they recorded the lessons, so kids who could not get onto a computer during the classes could try the activities on their own time.

“They can look at those whenever they feel like it,” Wright said. “On a Sunday afternoon that’s dull they can do one of those projects.”

For the field trips, VanSant organized pickups and rides to make sure anyone who wanted to come, and could make the time, could come with them. Parents often went with them when they could.

“The community, the compassion, the love, the empathy — you get there the best way you know how,” Wright said.

On the last day, VanSant said, the kids and teachers sat down together to talk about the experience.

‘They were following what we were doing, and they were liking it. They didn’t want to leave — they wanted to keep going. We put curiosity and kindness first. We put the two together. And I think they went up to it, 100 percent.’— Stephanie Wright

“We had to do two shifts with parents and kids,” she said, “because everyone wanted to come. We sat in two circles and went around and talked about something they learned and a gratitude and what they valued. I had tears in my eyes, and everyone said something different. Nothing was left out.”

They said they could see how they could learn now, in Covid, Wright said.

Damari’s younger sister, Cailee, 8 years old, told VanSant the program has made her feel more confident

Her oldest sister MOney, now 19, talked about community feeling and the love she has felt there. And Damari has taken on some of the organization to keep the program going in the fall.

The younger kids want to keep meeting, VanSant said, and Bridge is planning an ongoing monthly interactive gathering. Damari is creating a physically distanced Halloween event and supporting Bridge’s New Pathways conference, coming up Nov. 8, with professor, scholar and nationally known activist Angela Davis.