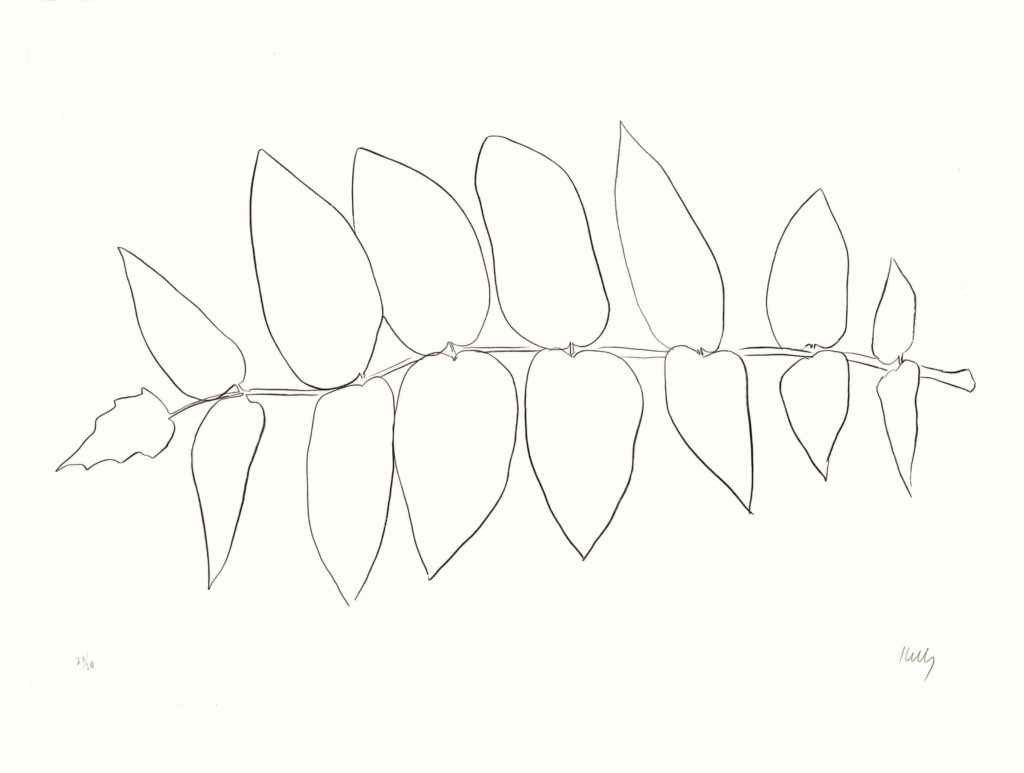

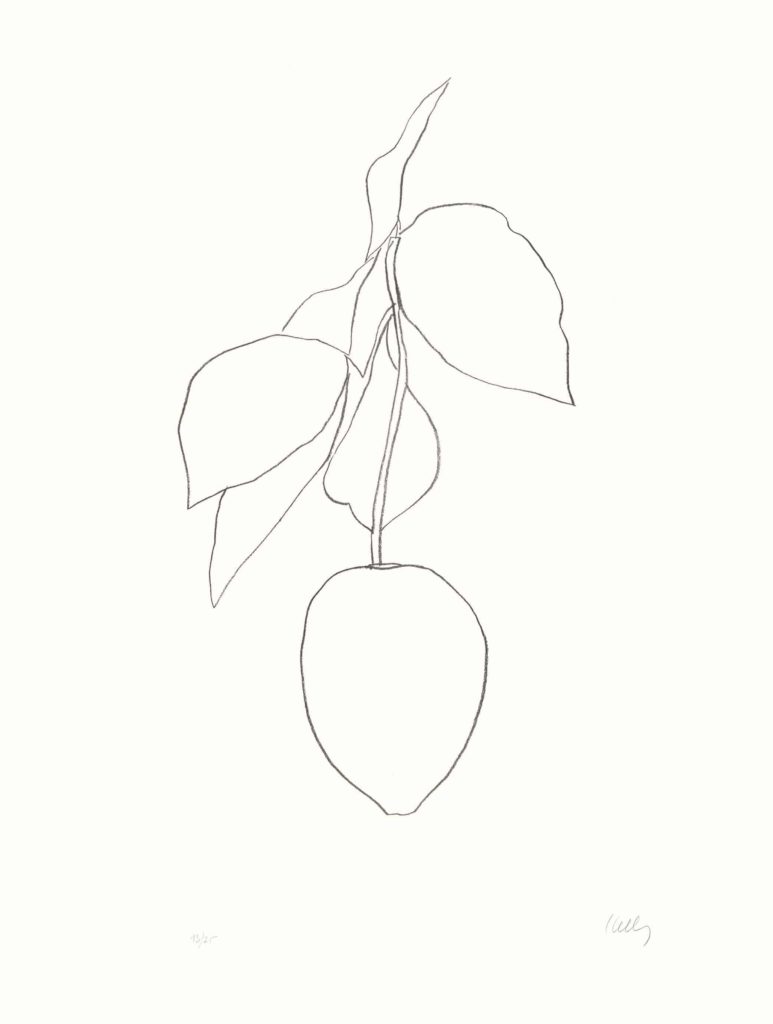

A line curves into a ripe pear, or a petal, or a stem. Walk through earth banks planted with larch, hawthorn and sporobolus grass and you’ll pass the stone lip of fountain with a flame at the center. Enter a doorway in a living wall of cyclamen, maidenhair fern and ivy — and here, in a restored 19th-century house, one of the most important painters, printmakers and sculptors of the 20th century has drawn the forms of leaves. Ellsworth Kelly’s Plant Lithographs, opened as the first national exhibition in the Leonhardt Galleries in the newly renovated Center House at the Berkshire Botanical Garden.

Kelly has held a leading name in the art world for more than 70 years. In the 1940s he served in World War II, and in the 1950s he studied in Paris and launched a career that would take him to the MOMA, the Whitney, the Tate, the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He became known for bright colors and hard lines, geometric abstractions, paintings on angled canvases or on several panels, metal sculpture.

And yet for more than 40 years, he has drawn the shapes of plants, and he painted quietly in a studio just over the border. He and his husband, Jack Shear, lived in Spencertown, N.Y., for 30 years, until Kelly’s death in 2015.

Shear, as the director of the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, curated and hung the exhibition, setting the prints against the light walls. The 20 lithographs rest below wooden beams, on clean plaster walls.

In renovating, the botanical garden has kept and emphasized the original form of the rooms, said Matthew Larkin, chairman of the board of the garden, who has had a hand in designing the new Center House. The broad boards in the wood floors were recovered and relaid in the renovation, and the doors are mottled like sycamores with the signs of time.

“We stripped it down to the bones,” Larkin said. “These minimalist and gestural drawings fit the place.”

Shear chose the 20 prints that hang here from a collection of 28 made between 1960 and 1966, and the foundation will rotate in new ones periodically in the summer and fall.

Madeline Hooper, vice chairwomen of the garden’s board, and her husband have known Kelly and Shear for 30 years and reached out to Shear for this summer’s show.

“It seems organically right,” she said, for Kelly and Shear to be part of the Center’s first summer at the garden, as 10 contemporary artists prepare sculpture for the gardens themselves.

Kelly and Shear both loved gardens and worked generously in their community, she said. He was prolific, and his work changed and evolved constantly over time.

“He was a very shy man,” she said, “and he worked all the time.”

He travelled, but he loved being home, working in his studio while his husband handled much of the public elements of his career. She remembers them sitting together in their own garden, a quiet place that felt as simple and modern and clean-lined as his drawings, planted with canna lilies and many kinds of trees.

She has seen him sit looking at a leaf or the sunlight on a wall. He would distill their shapes to a simpler line.

“He looked at everything in a way I’ve never seen another human being,” she said.

Larkin agreed, quoting the poet John Ashberry’s response to the plant lithographs, line without texture or shading or color: “They are not an approximation of the thing seen, nor are they a personal expression or an abstraction. They are an impersonal observation of the form.”

Kelly made some of these drawings from gardens in New York, and some in France — in Paris, Brittany, Cévennes, and Provence — as pencil studies in his sketchbooks, said Eva Walters of the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation.

For the lithographs he redrew his sketches and reworked them in a larger scale onto lithographic transfer paper, or he drew directly onto the transfer paper without a sketch. He had used this kind of transfer since 1949, in his first abstract painting, Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris.

“It had to be made exactly as it was,” she quoted in his words, “with nothing added.”

In late 1964, he came to Paris to work with Aimé Maeght, a French art collector and lithographer who owned galleries in Paris an Barcelona. Maeght had collaborated with well-known modernist artists, Walters said, including Henri Matisse — whose line drawings often inspire comparison with Kelly’s — Marc Chagall, Joan Miró, Alberto Giacametti and Georges Braque.

Kelly worked with Maeght and his master printer, Marcel Durassier, on two issues of Derrière le miroir, a journal for the artists who had given solo shows at his gallery. Durassier learned of Ellsworth’s plant drawings and suggested that they publish plant lithographs from his sketches, and they printed the collection of 28 in two suites, the first in 1965 and the second in the spring of 1966.

More than 50 years later, they have come to a garden he could have walked through on an early spring weekend, when the trees still show bare limbs, but the first buds and catkins are breaking through.

This story first ran in the Berkshire Eagle; my thanks to Features Editor Lindsey Hollenbaugh. Images in the story: Lithographs by Ellsworth Kelly, courtesy of the Berkshire Botanical Garden. Image at the top: Ellsworth Kelly, image courtesy of Jack Shear and the Berkshire Botanical Garden.