The music came from Louisiana. Two fiddlers sang swift, warm phrases in Cajun French, repeated like a private joke among friends. Mitch and Jen Reed, known among the best Cajun fiddlers in the country and champions of the potato waltz in their hometown, played as though they were sharing a potluck in their own music room, with a tub of recorders and penny whistles on the table.

They explained Louisiana house dances, a tradition of neighborhood parties with a musician to lead the two-step, and they encouraged everyone listening to get up and dance.

The sound man played the bones. A friend who had come up from Kingston, N.Y., to see them tuned his banjo. They were enjoying each other’s company, they were enjoying the music, and relaxed delight ran around the room.

They told the stories behind the songs they played. A man who saw a neighbor sprint out of her hen-house pursued by a (harmless) blue runner snake burst out laughing at his window and then picked up his fiddle.

“It sounds French Canadian,” I said to the standing bass and mandolin players at my table.

The Reeds had taken up a waltz — not the kind of waltz that glides like icing sugar on one note for each beat — the kind of waltz that bounces on its toes, rollicking up and down runs of notes without taking a breath. This waltz called for spins and turns and an eager pace.

The phrasing reminded me of Quebeçois tunes I had learned in the Maine pine woods at fiddle camp (on a wooden recorder; I’m a middling wind player, one note at a time. Chords are a sweet mystery.) Those Canadian tunes have a quick, pattering humor, always throwing in another few notes, pulling the dancers on.

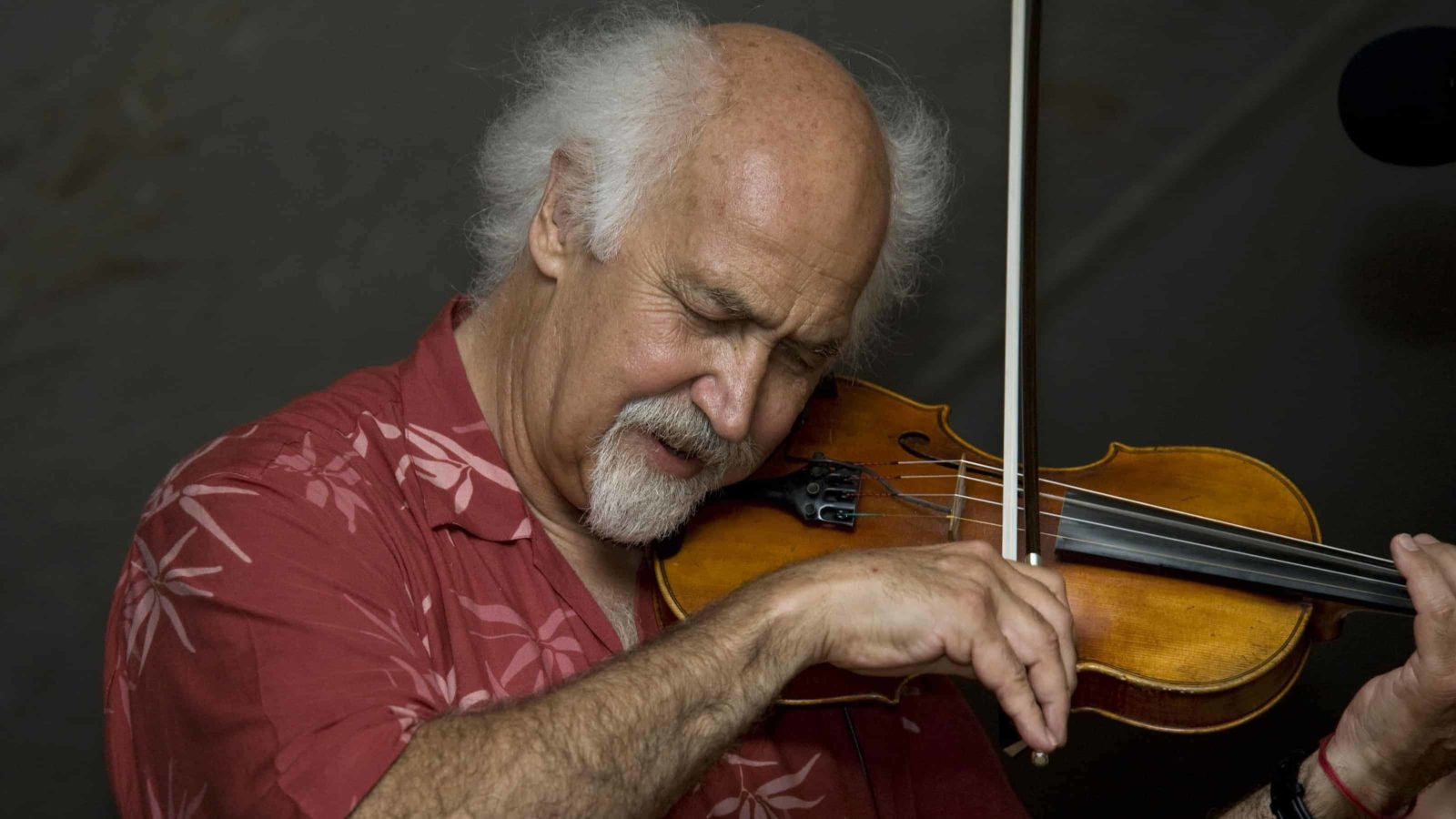

The mischievous humility in the call-and-response music sounded familiar too. Mitch Reed, the waltz champion, called out Pauvre Johnny peut pas dancer! (poor Johnny can’t dance), and brought me back to a stage in a tent on a summer evening where Quebeçois fiddler Guy Bouchard sang Ce sont les filles de St. Julie, putting a hand to his mouth at the chorus as though he had said something indelicate about the massive appetites of the beautiful girls, while his eyes danced.

It turns out I was almost right. Cajun is the Louisiana pronunciation of Acadian, and the Acadians were kicked out of Nova Scotia before the Boston tea party. Give me the descendants of French farmers playing music influenced by the descendants of African griots, and I am at home.

I had come on an impulse to Bounti-Fare in Adams on Saturday night. A flute-player from the music jam at Mass MoCA on Saturday mornings sent around an email about the concert. And here I was, sailing in a world I fell in love with in my graduate days in New Hampshire.

The Reeds’ house dances sound, note for note, like the picnics and dinners I’ve gone to on farms near Canterbury and Monadnock, where the hosts sell eggs still warm from the chicken at two dollars a dozen, and the guitars and fiddles and bodhrans gather around the wood stove, and someone sings the old marches. Someone calls a name or feels out a reel and someone else picks up a strum and the group catches on and the floor lifts off the room.

That kind of gathering can go on all night. You lose all sense of time in the music, and you look up hours later to find you’re out of breath and your hands are sore and you’re shaking with happiness.

Saturday night I was star-struck and too glowing to sit still. I bounced among the people I knew and laughed in the dancing contests, and two local guys waltzing together made my heart glad.

Then the banjo player, Tao Rodriguez, tuned up for a set and told us that his banjo had belonged to his grandfather — a guy by the name of Pete Seeger.

And then the Reeds invited locals to play with them.

Imagine it. These leading professionals are generous. Watching them together on stage, I had been thinking of the fiddle camp staffers who had played dances in their teens and cut CDs and come through Berkeley music school, playing with music as they played together, improvising, tossing around musical jokes, inventing harmonies, giving and taking the lead, speaking the language and losing sleep.

To sit in a circle with these people and feel a few notes, a piece of a melody or an underpinning, and feel part of the music, humbly and yet strongly enough for mischief, is a gift I will not forget.

This column first ran in Berkshires Week in my time as editor there, in March 2011.