The wall is a map and a memorial. Roughly 1500 handwritten toe tags form clusters push-pinned to the wall. In real, physical space, they mark places in the sand between Mexico, Arizona and New Mexico. Each one shows the last place of someone who died trying to cross the Sonoran Desert between the mid-1990s to today.

They form part of an art exhibit, Hostile Terrain 94, opening nationally and globally, from 2020 to 2022, and now it is open here.

After nearly two years of work and a pandemic in the way — as artists across the country talked with students and professors — Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts’ Gallery 51 has finally opened a show that starkly illustrates the violence and peril that exist around the US-Mexico border and the struggles and trauma of the immigrant and refugee experience within the U.S. The show calls people to take part, to understand and talk about the gravity and weight of immigrant experiences.

UCLA Anthropology Professor Jason De León created the map, and he found each place it marks. He is a trained archaeologist (he explains in the exhibit), and he and his team do field work in the desert. They collect objects people have left in their crossings, and sometimes they find the people themselves, that is, their bodies.

Everything they find, they place into a database, and each tag in the map explains that they have found a person who has died while crossing the border, many of them after they have reached the U.S. side. Sometimes they know only that someone has died. Sometimes they find their names, their photographs — sometimes they can talk with families in the countries these people have left.

Hostile Terrain 94 has grown out of this work. It is a participatory art project sponsored and organized by the Undocumented Migration Project (UMP), a non-profit research-art-education-media collective. They seek to memorialize the thousands of people that have died trying to cross the US-Mexico border.

HT94 is traveling the world, and at MCLA, the show has grown beyond this one project — as Erica Wall, curator and director of the Berkshire Cultural Resources Center at MCLA, has brought in nationally known artists whose work also encompasses immigration and many themes that belong to it. Around the map of HT94, Vietnamese American visual artist Trinh Mai Thạch has created installations and paintings, and the Sanctuary City Project by artists Sergio De La Torre and Chris Treggiari has created prints from conversations in the Berkshires.

Dr. Anna Jasayne Darr, associate professor of Sociology and Anthropology at MCLA, first brought HT94 to Wall’s attention, and the map has become a focus for people to come together and talk, even in Covid times.

Students and people in the MCLA community have written out the toe tags, and anyone who comes into the show can now take part. Two tables stand below the geolocated toe tag map of the desert, with more tags for visitors to complete to get closer to more than 3000 toe tags De León has found sources for.

The Undocumented Migration Project map of toe-tags asks for participation as it memorializes those who have passed away crossing the border.

MCLA students worked on the tags over the spring, filling in the information De Léon has gathered. They treated the experience with care, Wall said. Many students left notes to the lives they were honoring; with a closer look at the wall, some tags say, “happy birthday,” if a student writing the tag had noticed an individual’s recent birthday, among other messages.

“The journey across the desert is physically and mentally treacherous,” Wall said. “There is a rising mortality rate of people coming here seeking asylum. This has been happening for decades, and still has never found any real resolution.”

“We ask each individual that fills out a toe tag to consider the gravity of what they are doing. When you understand that you are creating a toe tag for someone’s life, it is intense.”

Now that the show is open, Wall is looking for people to help make the map more complete. The orange toe tags signify that a person has been identified by name, age and gender, she said, and the white indicate that a person has not yet been identified.

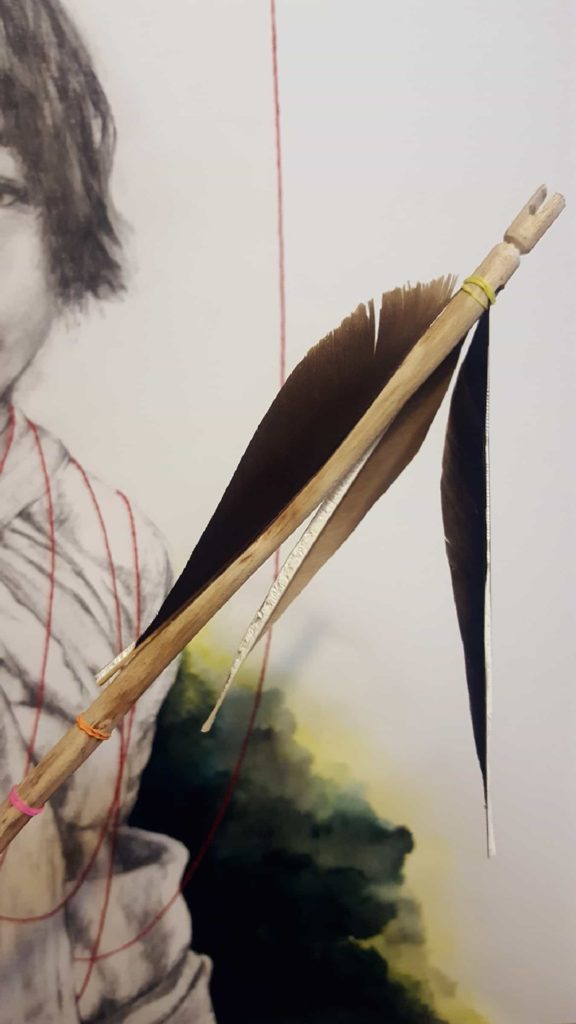

Trinh Mai creates arrows for an art installation in her studio in Southern California. Image courtesy of the artist. Image courtesy of the artist

Further into the gallery, next to the map, artist Trinh Mai’s work comes into view. Mai is a nationally known artist born in the U.S., and she lives now in Southern California. Her parents came to this country from Vietnam during the war, after Saigon fell.

She uses visual art as a tool to explore her family’s lives. Her paintings, collages and installations become an aperture, she writes, to tell the stories of “we, the enduring People” — she travels across mediums and disciplines with her work as she re-imagines her personal and inherited memories that convey an immigrant’s experience.

Mai’s That We Should Be Heirs extends on the wall past the Undocumented Migration Project map and, she will also invite people to take part in it. She has set openings in the wall, each as wide as the palm of a hand. The round holes are filled with a few scrolls wrapped in thin red thread, with pockets of colored yarn and a stone in each one.

“This experience is about preserving history and legacy, putting these stories of trauma and refuge in a sacred place,” Wall said.

The tiny scrolls are tightly rolled sections of unread letters from Mai’s Bà Ngoai, Mai’s grandmother, she explains in her description. The yarn comes from cotton grown at the American farm where her husband Hien’s family worked after they came to America from Vietnam, when he was a young child, and Mai collected the stones from the Pacific Coast.

Mai considers the Vietnamese belief of giving the dead a proper burial so souls can rest, Wall said. The installation will ask students and community members to bury their fears, traumas and burdens on handwritten scrolls on the wall. The stones in the holes represent this heaviness and pressure.

“For millions and billions of years, these stones have endured tremendous pressures,” Mai wrote. “They have been thrust against hard surfaces, tumbled over rough edges and broken down by violent falls, all to become exactly what they are — scarred but refined, imperfect but beautiful.They are us.”

‘This experience is about preserving history and legacy, putting these stories of trauma and refuge in a sacred place,’ — Erica Wall.

Mai’s stones form a pattern throughout her work in this exhibit, Wall said. They stand at the foot of a life-sized portrait — in Flesh of My Flesh, Mai has drawn and painted her husband, Hiền Văn Thạch. The stones ground him in the place his painting occupies, Wall said.

“The stones are from here,” Wall said. “(They hold) this idea of belonging and place, what you bring with you when you come here and what you make of it when you’re here, what you think refuge and sanctuary is, and your understanding of what you’ve left behind.”

‘(They hold) this idea of belonging and place, what you bring with you when you come here and what you make of it when you’re here, what you think refuge and sanctuary is …’ — Erica Wall

Hiền stands resilient to the aggression against him. Finches sit on his shoulders in bright paint against the charcoal drawing. Arrows outline him — real arrows. Mai has crafted them herself, by hand, as the Indigenous people of California have traditionally made them, and she collected feathers to fletch them and wood for the shafts on hikes along the coast.

“She made the arrows show his wounds,” Wall said, “some apparent and others not apparent. She says ‘I want you to see the scars.'”

Psalm 91 inspired the portrait, Mai writes: “You will not be afraid for the terror by night, nor for the arrow that flies by day; A thousand shall fall at your side, and ten thousand at your right hand, but it will not come near you.”

She made it as a prayer of protection against the forces against immigrants in the US, she writes, against ICE and other structures of persecution.

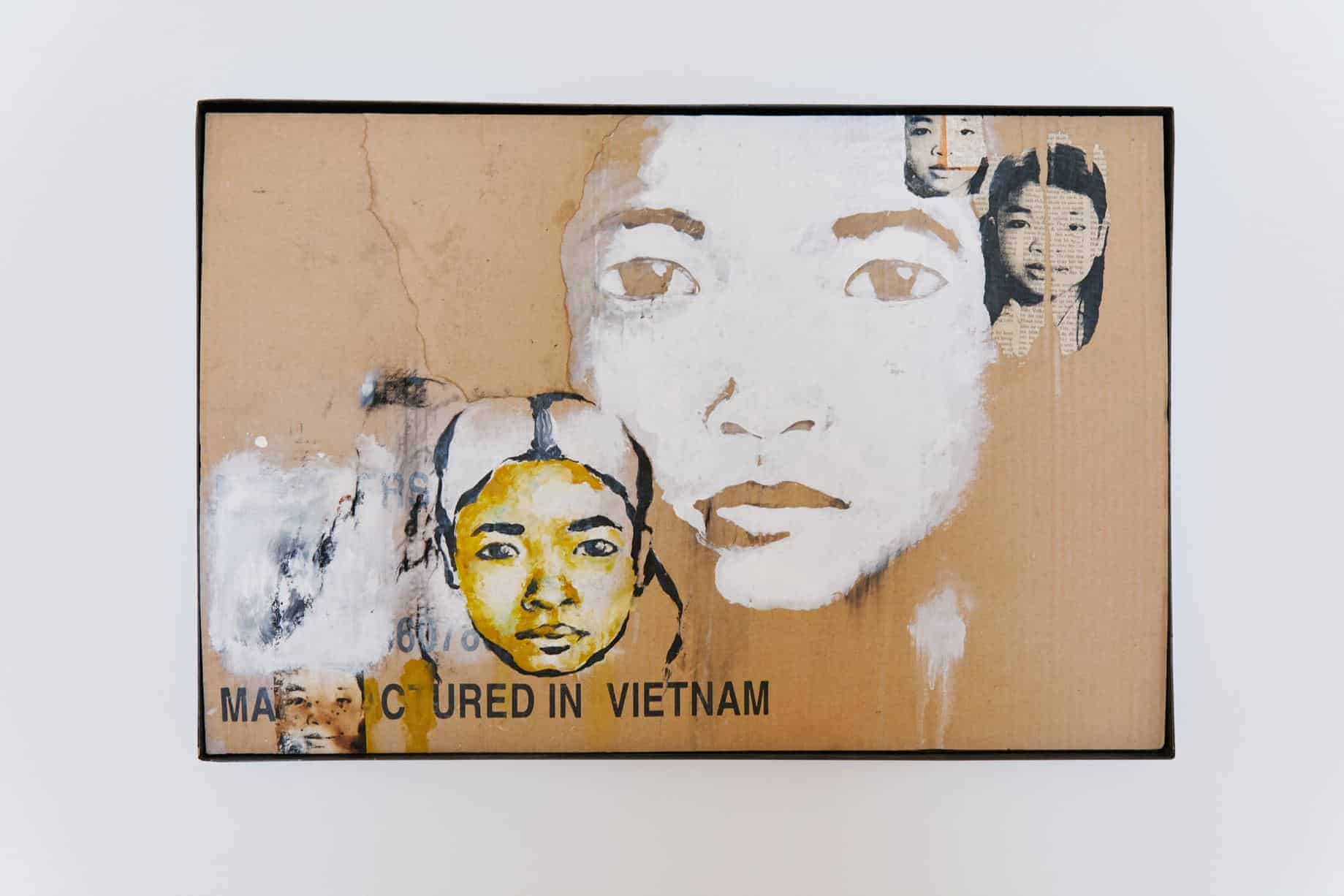

Mai's Ma cured in Vietnam is a portrait of her mother at age 17.

Across from the portrait of Hiền, a woman looks out in a collage of portraits, all images of her. In acrylic, ink, oil and Vietnamese newspaper, Mai has painted her mother as a young woman 17 years old, on cardboard from a box her family brought when they came to the U.S. Words are printed on the side, and Mai has obscured some of the letters — the ones left now read Má Cured in Vietnam.

She combines of memories and folklore — solid objects and photographs wound through with symbols, like the arrows, like the scrolls, carrying strong feeling.

Finches fly through many of her paintings. In And we shall come forth as gold, an American goldfinch carries a child by thin red string through the air, lifted from a golden landscape, in acrylic, charcoal and gold leaf. Mai has painted faint white finch images painted onto the light background, and they are easy to miss without a closer look.

From the Snare of the Fowler, tells the story of a Vietnamese greenfinch, Mai explains, as the bright green and yellow bird works tirelessly to untangle two refugee children from the snares that befall them.

The finches are messengers from Vietnam that offer hope for flight and movement out of the tragedies of the moment, Wall said.

“Each immigrant artist we’ve worked with conveys that their migration was worth it,” Wall said. “Worth the risk. But even if it may be ‘better’ here, what it means to be here is incredibly complicated too. …

The string is intertwined — it’s not really letting you go. It’s a continual process. It binds you, and you can still be living your life normally — and it’s still there. The birds give a sense of hope, that we can move out of this, but it’s always there.”

Her work may be subtle, but it runs deep she said. She sees Mai’s work standing in contrast to the bold prints of the Sanctuary City project across the gallery.

“Trinh asks for care and participation in a more particular way,” she said.

‘The Sanctuary City Project challenges the weight and meanings these words have in our conceptions of migration.’ — Erica Wall

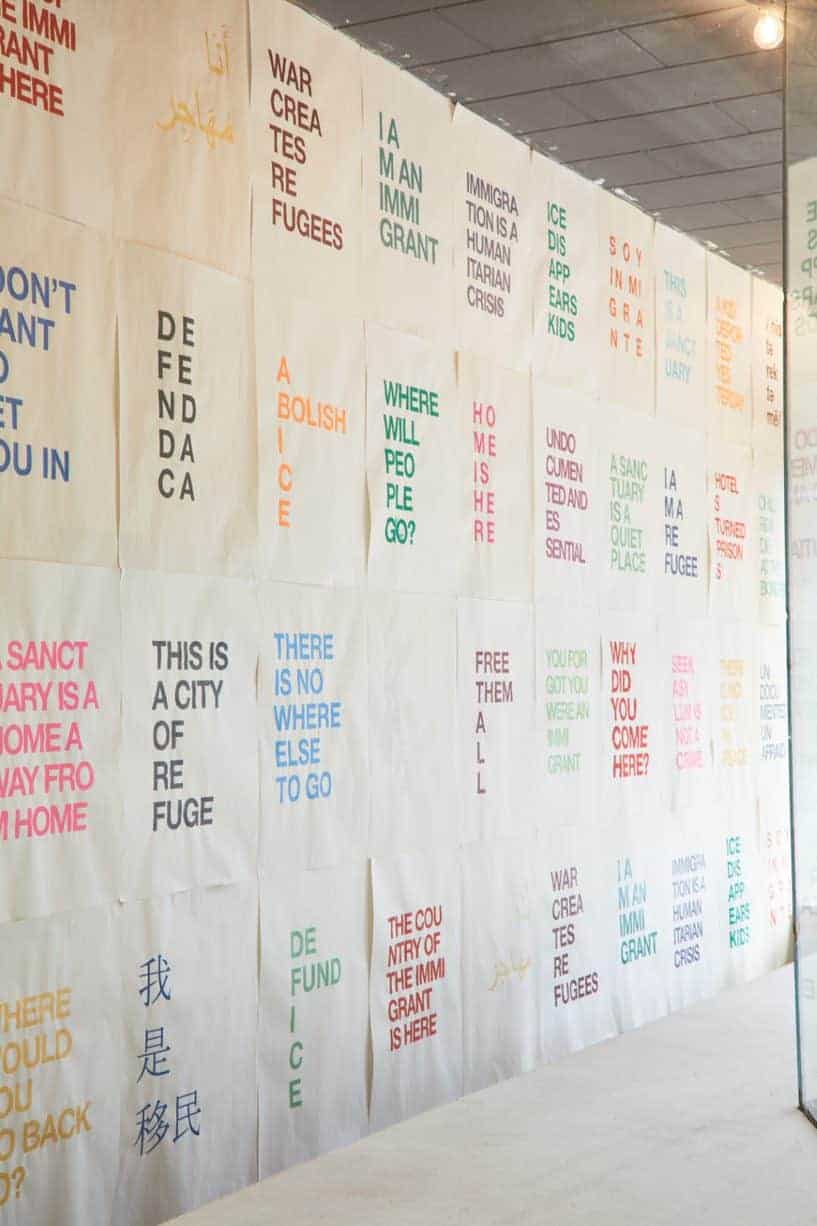

Across from Mai’s delicately curated work, the Sanctuary City Project has set bold vinyl letters to line the opposite wall — UNDOCUMENTED.

“You can read the word UNDOCUMENTED in many ways,” Wall said, looking at the word as the syllables come slowly apart on the wall: “Undo, do, men …”

The vinyl letters UNAFRAID stretch along the floor, read on the wall as raid, afraid, aid …

“The Sanctuary City Project challenges the weight and meanings these words have in our conceptions of migration,” Wall said.

The Sanctuary City Project's Undocumented/Unafraid vinyl can be read in multiple ways.

Most of the work of the Sanctuary City Project takes the form of more than 30 original screen print posters that evolved out of the stories and complexities of the immigrant experience gathered by community interaction data and immigration research.

Artists Sergio De La Torre and Chris Treggiari started the project as research in 2008, as detailed on the SCP website, and the idea stemmed from their interest in the idea of a Sanctuary City after the San Francisco Bay Area experienced many immigrations enforcement raids. In 2017, the project began its public engagement with the Sanctuary City Print Shop at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts.

De La Torre and Treggiari’s work open dialogue through billboards and posters within a community, Wall said, asking questions to provoke thought and start conversations. Their projects use bold print to point attention to ideas of immigration, belonging and social change, while they also seek to directly address the violence and death of individuals crossing the U.S.-Mexico border.

The bright SCP Posters cover walls in Gallery 51.

Through 2020 and the pandemic, Wall, BCRC and the Sanctuary City artists collaborated to produce billboards that displayed questions and a phone number to call to answer. Each billboard asked one of two questions: Why did you come here? When did you forget you were an immigrant? The billboards stood throughout Pittsfield and North Adams, trying to engage the community in the SCP’s research work.

The SCP print posters, banners and data projections bring the realities and tragedies of the immigrant experience into the MCLA and surrounding community, as they seek to provoke change and action.

In the spring, De La Torre and Treggiari displayed posters around the MCLA campus, and now they stand brightly as part of the Gallery 51 exhibition Hostile Terrain. They are short quotes in bright ink on an off-white background. One reads, “A sanctuary is a quiet place.”

The billboards sparked conversations between community members and the SCP, Wall said. Many of the people who chose to respond answered positively — many people in the Berkshires have connections with immigration at different times — English and French incomers in the 1600s, people from many parts of Africa who were forced to this country and made lives here, Italian and Irish, French Canadian, Polish and Chinese mill workers a century ago, new families from Africa, Central and South America and Mexico …

‘The students were challenged to think about how they see their own family story, and what it means to be an immigrant,’ Wall said.

The artists have felt some pushback as well, Wall said. In the billboards and in class discussions, the artists have talked with people who have not considered themselves as an immigrant or thought about the connections to migration in their family history.

“Many times, we separate ourselves from attachments to ideas of immigration,” she said, “but these ideas are not far removed from all of our family histories.”

De La Torre and Treggiari worked with Melanie Mowinski’s Introduction to Design course at MCLA, and they created their own posters about immigration in the same vein. The artists asked the students to think about their own connections to experiences of migration and belonging, and they created print designs after interviewing family.

‘There are a lot of intersections in the stories of immigrants, and the main intersections are the trauma, the fear and the not belonging.’ — Erica Wall

“The students were challenged to think about how they see their own family story, and what it means to be an immigrant,” Wall said.

Student artists Ana Sheehy, Jack Vezeris, Ryan Powers, Paige Wandre, Joseph Vigiard, Andrew Cruisce, Sean Soucie, Ian Crombie, Abby VanSteemburg, and Alana O’Connor have created 12 student posters, and they hang across the gallery from De La Torre and Treggiari’s prints.

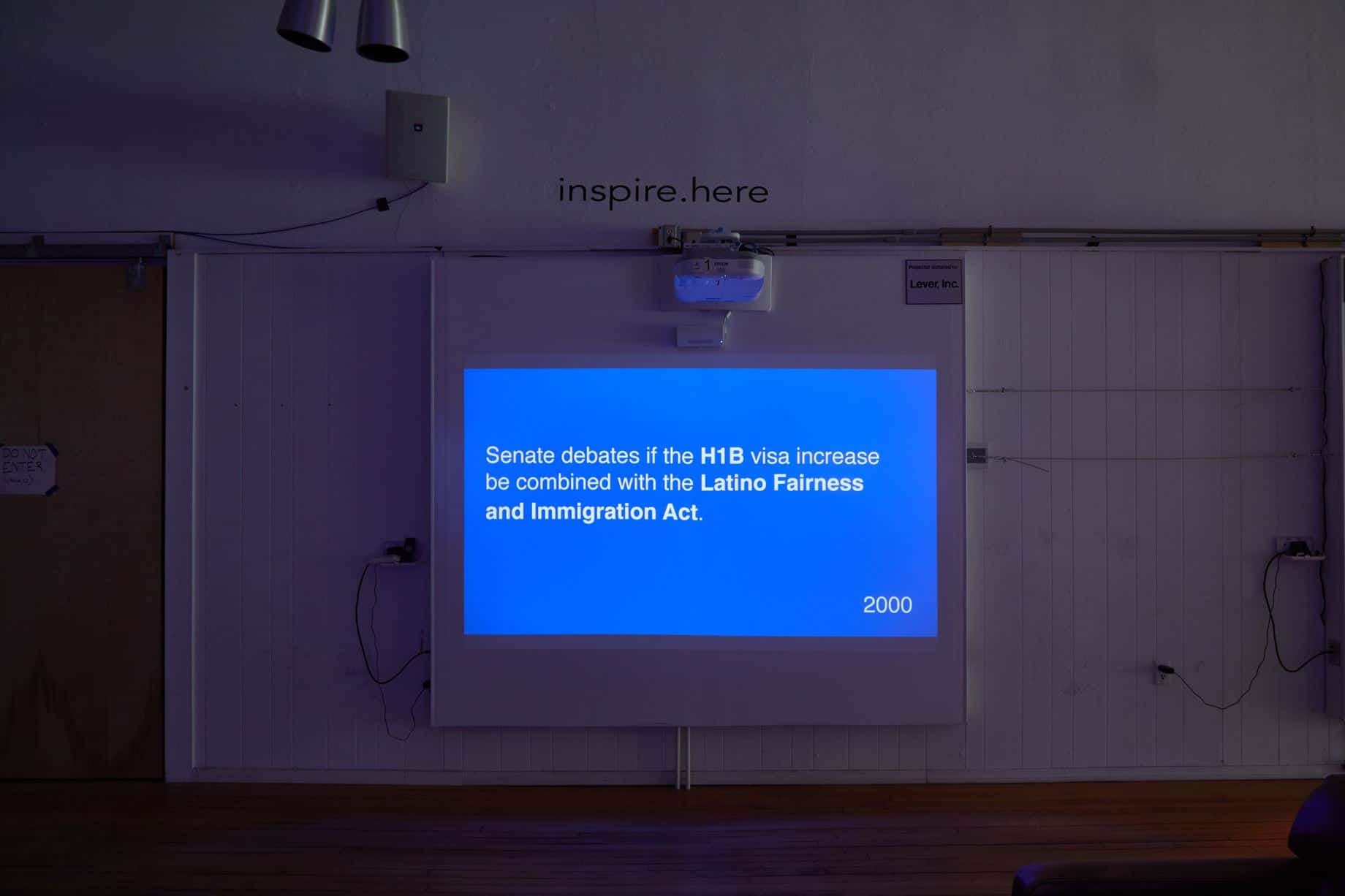

Farther along the same wall, brightly colored screens show facts about government policies on the South-Western border in the past few decades — decisions and changes to laws — and numbers that show how they have affected people. The projections point to forces that have changed and forces that have not, Wall said, and they share incidents and major policies that many people may not even be aware of.

“There isn’t any sort of resolution (in these projections),” she said. “They just ask for awareness.

They are a video documentation of policies around immigration along the Southwest borders, and in each administration, something changes or returns to what it was. It looks like something will be addressed or resolved, and another policy sets that back. … Sergio De La Torre says it’s ongoing, and it’s not just in the Southwest … and not just in the U.S.”

The SCP Projections alternate through a series of facts, laws and statistics.

When the sun sets on the ‘First Friday’ in August, anyone walking around downtown North Adams will see another kind of film projection coming into the open.

Gallery 51 will introduce a new pedal theater — a bicycle fitted with a projector and sound system that travels behind in a hitched carrier. The bike makes the theater portable and also powers it as someone volunteers to keep the wheels turning.

In August it will make rounds around downtown North Adams, and Gallery 51 will project videos by five immigrant artists who have created new work from their experiences, as Wall continues to move into the Berkshire community with stories topics of immigration and belonging.

The SCP’s work and Trinh Mai’s, and the Undocumented Migration Project, all encompass these efforts to bring the urgent circumstances of US immigration to the forefront of community conversations, she said.

“There are a lot of intersections in the stories of immigrants,” Wall said, “and the main intersections are the trauma, the fear and the not belonging. These intersections are important, and we all can connect to them. We need to keep finding intersections in our stories.”