Artist Trinh Mai works on a life-sized portrait of ehr husband, Hien, as she creates an art installation in her studio in Southern California. Image courtesy of the artist.

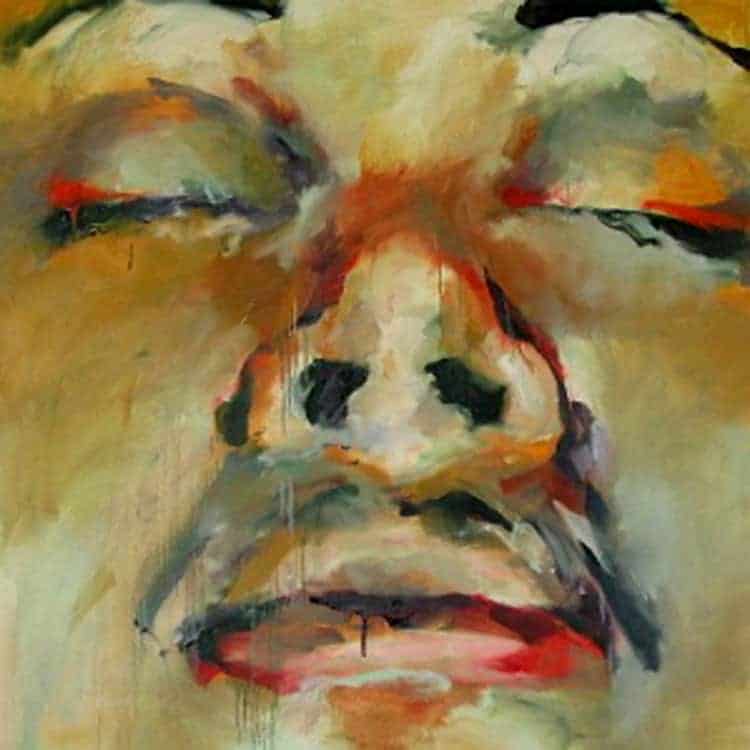

In her studio in southern California, Trinh Mai Thạch turns to show a life-sized portrait of her husband, Hiền Văn Thạch. She has drawn him in charcoal, tall, broad-shouldered, muscular. He stands with his hands at his sides, looking out at anyone who looks up at him.

“There he is,” she said, “vulnerable.”

She is an artist exhibiting nationwide in museums, universities and arts centers from San Diego and Seattle to Minnesota, to Cambridge, and she describes Hien as a man of compassion and strength. She met him as a football player at San Jose State. He came to America as a young child and grew up in a close family in a poor neighborhood in the central valley of California. He has studied immigration law and works with teenagers facing the kinds of challenges he has faced, helping them to win scholarships, to get to college.

He stands in this portrait with his weight balanced and his hands open. She is expanding a new work around his image, she says. She may map his body, and his scars.

This one, she said, holding a print she has made of the design on his skin, was never stitched. He would not go to the hospital then, he told her, because it would frighten his parents to see him that way, and he loved them and would not cause them pain.

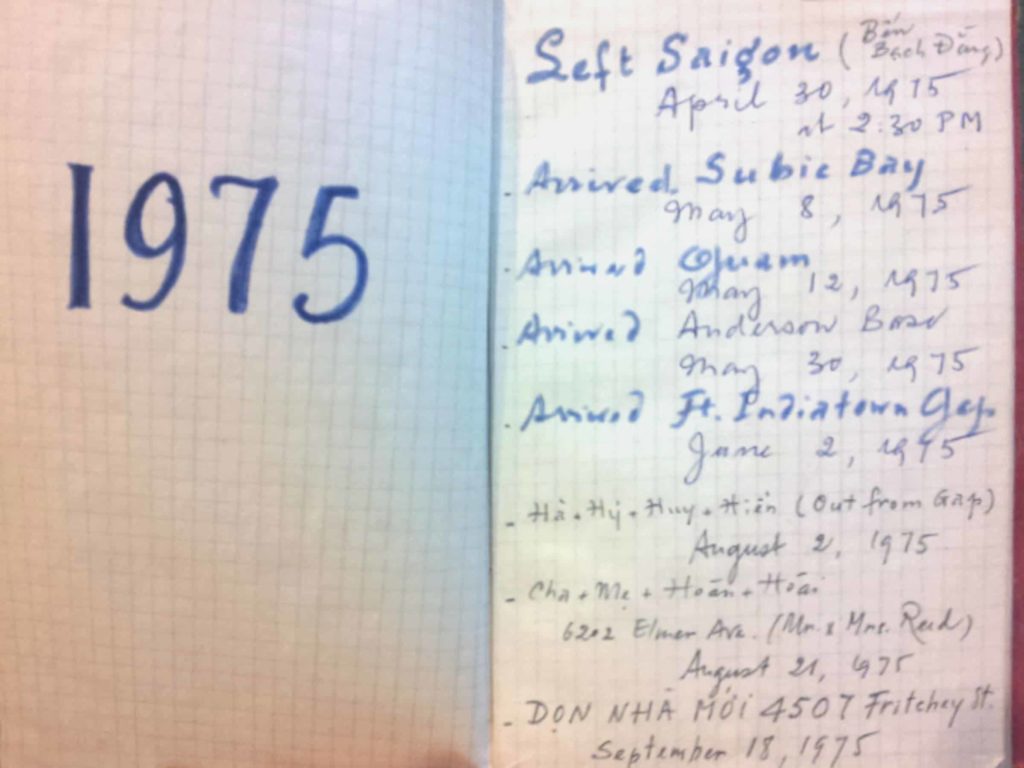

Hien is Vietnamese Cambodian American. Trinh Mai was born in Pennsylvania, and her mother’s family left Saigon in 1975 when the city fell. They got on a boat and hoped it would get them away, she said. Her father’s family also came from Saigon to Harrisburg with their own risks. Growing up, she would sit at the foot of their bed, and they would tell her stories about the homes they had left, the family they loved and their lives here before she could remember.

Family stories and experiences move deeply in her work, and she will talk with students in the Berkshires this fall and with the community as she works toward an exhibit at Gallery 51, an artistic collaboration and a global conversation around immigration that the Massachusetts College of Libaral Arts will hold for a full year.

Throughout fall 2020 and spring 2021, MCLA will take part in Hostile Terrain 94, an art installation happening this year across the country and around the world. Installations are opening in America before the election, as its themes encompass national debates.

HT94 grows from an art and research project MacArthur Fellow and UCLA anthropology professor Jason De Léon has created to remember the names and the lives of people who have died in the Sonoran Desert along the Mexican American border and to talk about the policies that have shaped that border land and the people who travel through it.

In the Berkshires, projects are growing around this installation, and MCLA will invite the community in. Professor Anna Jaysane-Darr has created a course around HT94 with virtual programming. Sanctuary City Project artists Sergio de la Tour and Chris Treggiari are holding a conversation in texts and in ink and, they hope, in person.

And they and Trinh Mai will talk with students and the community this semester, as all three artists prepare to show their work together at Gallery 51 this winter.

‘How many hundreds or thousands of miles did these feathers carry these birds, to arrive in a new place or the place where they were born, to bring a new generation into the world?’ — Trinh Mai

Trinh Mai plans to bring her portrait of Hien across the country.

“It is inspired by Psalm 91,” she said. “I have been thinking about prayers of protection, thinking of a verse. Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night, nor for the arrow that flyeth by day … a thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand, but it shall not come nigh thee.”

She memorized it so she will have it in mind as she works. And she thinks about arrows flying.

“Who are that thousand, that ten thousand? Children, families, people deported, families torn apart. How are we going through this — how is it in this crisis, when tens of thousands are detained and even more are fighting their immigration cases, that we can consider these the fortunate ones because they are still living? What doess this say about the state of the world?”

As the work takes shape for her, she has learned to make arrows by hand as the indigenous peoples in Southern California would make them traditionally, and she is awed by their genius.

She and Hien went hiking and found the wood for the shafts. She straightened them in water and over flame. She gathered feathers on their hikes, and one night as they drove home, Hien saw a great horned owl on the side of the road, just hit by a car.

“It was a magnificent creature,” she said. “I thought, I can’t take it … What should we do to honor it?”

And Hien looked up at her and told her this is a once in a lifetime chance. She could study it and see it closely and bring it into her art. The owl is a permanent resident, not a migratory bird. So she has learned to preserve the feathers, soaking them in three baths of water and laying them in the sun like a kiln. She holds up another shaft with mallard feathers, and in the sun they glow a dark iridescent blue.

She often involves birds in her work, often in high color.

“How many hundreds or thousands of miles did these feathers carry these birds,” she said, to arrive in a new place or the place where they were born, to bring a new generation into the world?”

The Sanctuary City Project welcomes all comers to print signs at its mobile print shop. Press image courtesy of the artists.

‘The Country of the Immigrant Is Here’

In the Sanctuary City Project, de la Tour and Treggiari follow a timeline of immigrants’ experiences across 30 years. de la Tour is an associate professor at the University of San Fransisco, and Treggiari a teaching artist in residence at California College of the Arts, and they have collaborated on this installation over the past 10 years, from the Guerrerro Gallery in a warehouse in San Fransisco to the San Fransisco Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego, Minnesota Street Projects, Seattle University .…

Their timeline begins in 1989, when San Fransisco became a Sanctuary City, and it moves into the present, tracing the experiences of immigrants in America and the changing laws and policies that affect them. de la Tour and Treggiari want to open a conversation, they say. These experiences, present and recent past feel deeply timely to them, and they have talked with many people who have known little about them.

They have gathered years of research from articles and essays and government organizations; they show film footage of public gatherings across the country, and they surround them with a collage of prints made by hand.

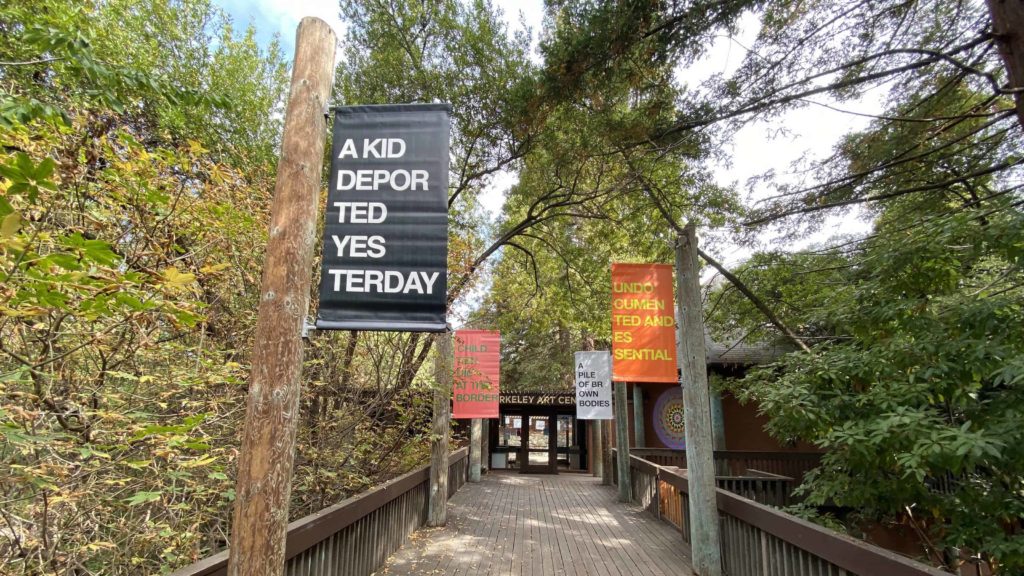

They begin by asking questions — When did you forget you’re an immigrant? What would you tell an immigrant? Traditionally they collect an archive of responses, and then they set up a mobile print shop. They spend time in a gallery or art center two or three days a week for several weeks. They silk-screen posters from answers they find compelling. The country of the immigrant is here. Why did you come here? A sanctuary is a quiet place. Undocumented and unafraid.

And they invite anyone who walks in to join them. People can feel and see the printing, push the ink across the screen and talk with them.

In the Berkshires, they are adapting to the pandemic and the practice of doing this work from 3,000 miles away. They are asking their questions publicly, on billboards, on postcards, in conversations with students and nonprofits and community groups. They invite anyone to reach out with an answer.

They want to hear diverse thoughts, Treggiari said. They want to talk with anyone who will genuinely talk with them.

de la Tour remembers a woman coming up to them one day. She looked young, white, punk-rock, and he thought she would see his point of view. She told him she didn’t understand why it was important to provide refuge to people escaping wars or climate change or violence — why should America be concerned?

“I asked her, who are we and they?” he said. “She said ‘we are Americans.’ And I said ‘I’m an American too.”

They could talk about the history of this country, and when and where her own family first came here.

“Be honest,” de la Tour said. “We are your teachers and your janitors, your boyfriends and girlfriends and lovers. We are your grandparents. We cook your food, drive your buses and bring your mail. Know who you are.”

The Sanctuary City Project creates installations with signs the artists print in their mobile print shop. Press image courtesy of the artists.

Hostile Territory 94 maps loss

The Hostile Terrain 94 installation opens its own conversation, through research, on what has happened on the U.S.-Mexican border across several decades.

In the mid-1990s, the U.S. adopted a policy of ‘Prevention through Deterrence.’

“The point was to funnel immigrants into the most dangerous points of crossing — the desert” said Jaysane-Darr, “shoring up the boundaries around towns. The idea was that people would choose not to cross. That hasn’t happened.”

What has happened, she said, is that more than 6 million people have tried to cross the desert in the last 20 years, according to De Léon’s research, and thousands of people have died.

His Undocumented Migration Project has analyzed the effects of the policy since it began. Industries have grown around getting people across, Jaysane-Darr said — traders selling the travelers water jugs and equipment, guides and smugglers taking money to get them into the U.S. … or leaving them abandoned, extorted for money and robbed in the desert. And now an industry is growing surrounding detention camps, privately owned prisons and children separated from their families.

Her class, and MCLA, will come together to understand De Léon’s research and the people who have made this journey. The art installation will set up a visual image of the border, she said, and she and her students will create toe tags following De Léon’s guidelines, one for each person known to have died on their way.

One color will show when the body is identified and the artist knows their name at least, and another when De Léon knows only that some remains of a person show that someone died there.

MCLA will open the project to the community to be involved, Jaysane-Darr said. the idea is that people will fill in the tags in a group, to share the experience, though in Covid-19 they may not be able to share the same space. They will fill in whatever details De Léon can give about the person their tag represents. They can write a message on the back if they want to. And then the tags will go up on the gallery wall, along the line that marks the border, at the GPS coordinates where each person fell.

“It’s a witnessing, Jaysane-Darr said, “an honoring of the dead.”

Trinh Mai weaves stories through generations

Words and memory run strongly in in Trinh Mai’s work, as in Biển, Biến, Biến, portraits of people who have looked for freedom in a time of war and have died.

She will talk with students about her work in October, and with the community. She is planning a workshop on physically erasing fear, recalling a project at the San Diego Art Institute when she wrote the word fear itself in massive letters in graphite pencil and then invited people to help her physically erase the word by hand.

“There are fears that protect us and warn us of danger,” she said, “and there are the fears we grow in our own minds and hearts that hinder us in doing the things we know we ought to do, like taking a stand on things we believe in.”

This winter at Gallery 51, she will ask people to write about their fears. Write on a strip of paper. Roll it into a scroll with the words facing outwards, so they will touch the words they rest near. Bind the scroll with red string. Choose a stone and feel its weight. Then bury the stone and the scroll together.

These scrolls and stories form the core of her installation That We Should Be Heirs, as it has crossed the country. She has exhibited at the San Diego Art Institute and at the University of Washington in Seattle, led a workshop at Harvard, and now she will bring the work MCLA.

“It is inspired by a Vietnamese belief that to give the departed sound rest, we need to bury them,” she said. “What if we could bury our fears to give our minds rest?”

She begins with her own family stories and objects that hold meaning: “Bà Ngoại’s unread letters, cotton grown at the farm from which my husband and his family harvested when they first arrived in America, hand embroidery, holy water, stones collected from the Pacific Coast … Pacific Ocean water and wool.”

With the words people write, the fears they share, she creates a space where people can feel safe enough to sit with those feelings.

One student who worked with her told her, “I had to wait until everyone left the gallery, because I needed to be by myself in the gallery to address these fears.”

It was hard for them. It was painful. But it was a relief.

“If we could bury these fears,” she said, “we could make decisions with … sound mind and in confidence.”

She thinks of decisions made in panic — people who have given all of their savings to immigration lawyers who aren’t doing their jobs, people who have sold their homes, people who will do anything to protect the people they love.

That We Should Be Heirs can touch inherited trauma, she said.

“It’s so real. It’s in us physically — and also emotionally and spiritually and mentally — but it’s in our bodies. It saddens me that there’s less talk about inherited strength.”

She draws strength from her husband and her family, she said. She and her husband are supporting people who are fighting their own immigrant cases, people facing deportation.

She thinks of people who have been deported to Vietnam, people who had left war and persecution to find sanctuary and knew they faced danger if they were forced back. She knows of people who have had to go back and now are missing.

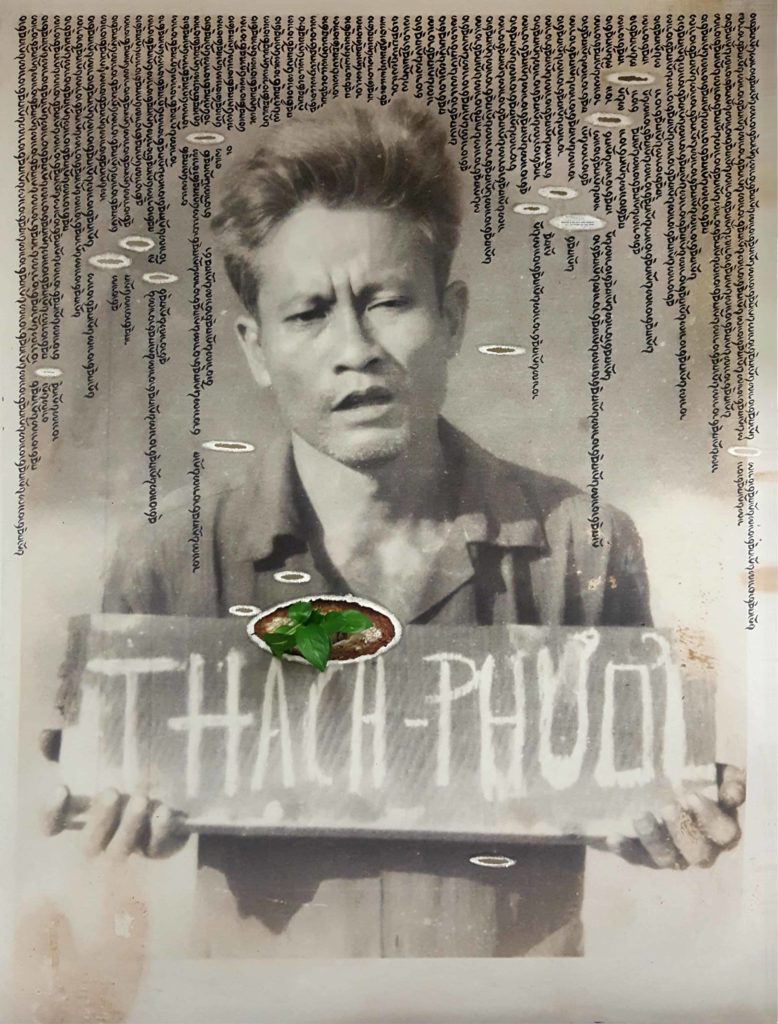

She looks at a photograph of Hien’s father, Phơưl Vân Thạch. It was taken while he was a prisoner of war in a re-education camp, she said. He holds a wooden sign: Thach-Phuol.

“His father was shot 17 times in the war,” she said, “and he survived.”

Once the blast was strong enough to throw him into the Mekong River, and the river carried him away.

“His hands are so gentle, even holding that heavy board.”

‘It saddens me that there’s less talk about inherited strength.’ — Trinh Mai

Trinh Mai’s parents worked hard for her and her brother.

“I am working as an artist because they supported me,” she said. “I’m privileged. They came with nothing.”

Her father and grandfather could draw beautifully, she said, remembering her grandfather’s sketches in the pages of her grandmother’s cookbook. Her mother loved music. In Pennsylvania her family would translate U.S. news into Vietnamese, put on concerts, cook for their neighbors to introduce them to the culture.

Her family moved to San Jose in the tech boom, she said. Her mother is an engineer, and her father works in technology.

Hien’s father had been an officer in Vietnam. In the U.S. his family worked in the fields when he was a boy. They had to help each other to put food on the table, she said. His mother packed lunches, and she was in charge of the younger kids. They were in the pepper fields, carrots, garlic, alfalfa. He was paid $1 a bucket to pick garlic, and the picking would cut his his hands. Worms in the alfalfa would stain their clothes purple.

And he remembers the cages where the farmers would catch birds to keep them away from the crops. His family would go into the cages and take home birds for dinner. They would put them into rice bags they had sewn with drawstrings to hold them closed.

“One day,” she said, “he’s in third or fourth grade, and he went into the cage and caught the bird. He was holding it, and he could feel its heart beating heavily. And then it started to speed up. He felt that it was afraid. He heard the noises it was making.”

He let the bird go. His mother saw, and she called to his father, “do you see this? Our son is letting the birds go.”

His father asks him why, and he says it was afraid, and I didn’t want to see it afraid. Then his father asked him, do you want to let all the birds go? And that day, they did.

“He and his dad are of one heart,” Trinh Mai said.

His father felt his compassion and honored it.

Not long after that, she said, Hien came home from school one day and found a Mexican family in the kitchen. They were living out of a van, and his father had invited them home. Hien and his family were living in a two-bedroom apartment, eight people together. Now 11 people shared it. They had no common language, she said. His family speaks Vietnamese and Cambodian, and the Mexican family spoke Spanish, and they lived together for a year.

“How would you explain this experience,” she said, “except through hardship and a need to survive? They communicated through food. The women cooked together and the children would play together.”

He still remembers the chile verde he tasted for the first time in that year they lived together.

***

MCLA and the Berkshire Cultural Resources Council will hold events and programming through the fall with Hostile Terrain 94 and the artists involved and more, including a community read and a series of virtual artist talks — Filling out toe tags on October 6 and November 10 and Artist talk O.M. France Viana on October 10, Vincent Valdez on October 17 and Trinh Mai on October 29