“There were people on the café terraces, boys and girls on the boulevards, bicycles racing by on their fantastically urgent errands. Everyone and everything wore a cheerful aspect, even the houses of Paris, which did not show their age. Those who were unable to pay the steep rents of the houses were enabled, by the weather, to enjoy the streets, to sit, unnoticed, in the parks.”

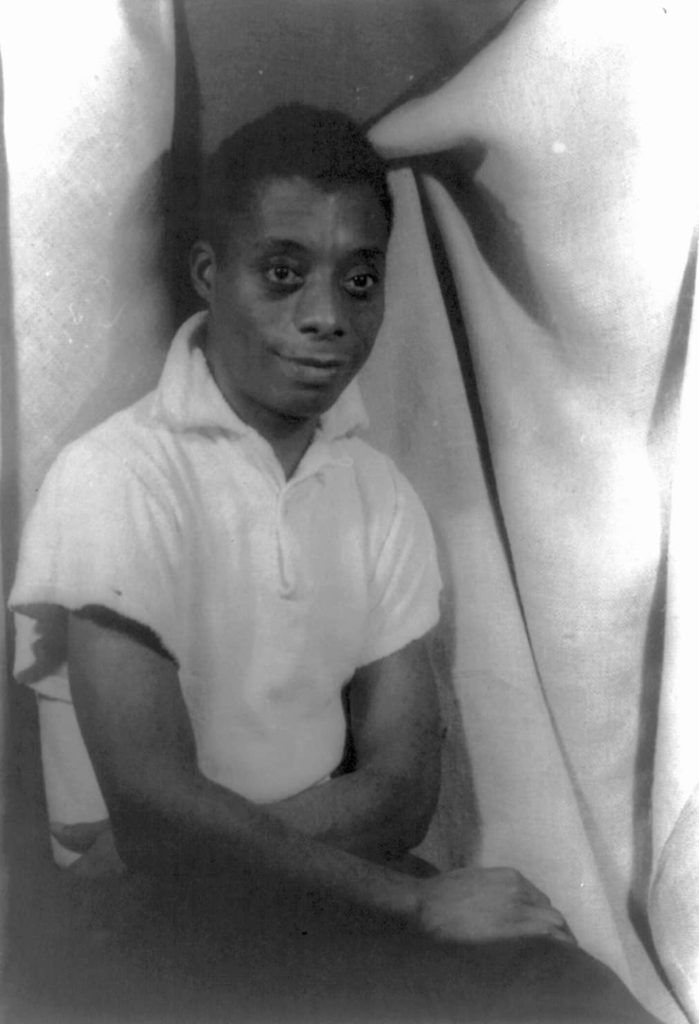

On a late summer morning, James Baldwin wrote about the newspaper vendors and the people waiting outside the bakeries because of the bread strike. He was waiting for the Conference of Negro-African Writers and Artists to begin at the Sorbonne. It was September 19, 1956 — he had lived in Paris for eight years and expanded his reach as a writer internationally. He had published two novels and a collection of essays, and he would spend the weekend with intellectuals from Africa, Europe and America and write about their conversations in a story for Encounter magazine.

His account of this weekend of conversation reaches around the world — Baldwin listening to Aimé César and Richard Wright, and to M. Lasebikan of Nigeria speaking in Yoruba and English on the structure and beauty of Yoruba poetry, “from the devotional to a poem which described the pounding of yams … a poem about the memory of a battle, a poem about a faithless friend, and a poem celebrating the variety to be found in life.”

As Baldwin describes it, that weekend has something like the feel of college days, the lights in the quad at night, curious people meeting in hallways and common rooms and leaning together in seats scooped out of sculptures on the lawn, talking until the night gets light.

And at the same time that conference had a political power I find hard to imagine now. No one had seen anything like it — not in centuries — a Yoruba poet walking into a hall at the Sorbonne and setting his country’s writers in conversation with Baudelaire and Balzac — and his country’s artists with Van Gogh, who wanted to see Africa and never did, or Picasso, who appropriated African masks and geometries in his work.

‘ … the days when we walked through Les Halles singing, loving every inch of France and loving each other … the jam sessions in Pigalle … the morning which found us telling dirty stories, true stories, sad and earnest stories, in grey workingmen’s cafes.’ — James Baldwin

I first read Baldwin’s account, “Princes and Powers” in the collection Nobody Knows My Name on a spring day, as a documentary on Baldwin’s life came to Mass MoCA to launch a summerlong Lift Ev’ry Voice Festival and I prepared to interview the film’s director.

Three months later, on a September evening, Kate Bolick and Darryl Pinckney spent an evening talking about Baldwin in the opening of the Touchstones series at The Mount in Lenox. Bolick, a bestselling author, journalist and contributing editor to Atlantic, curates conversations with writers she admires.

She sat down with Pinckney — a novelist, journalist, longtime contributor to the New York Review of Books, Slate, Granta and others — to talk about his work and his recent time editing a new Libary of America volume of Baldwin’s later novels: “If Beale Street Could Talk,” “Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone” and “Just Above My Head.”

Baldwin wrote more than 20 books in his lifetime, fiction and nonfiction, plays and poetry, and he fell for words early on.

“I read ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ compulsively, the book in one hand, the newest baby on my hipbone,” he wrote in “The Devil Find’s Work” — 8 years old, an older brother caring for his younger sisters, reading “A Tale of Two Cities” while his stepfather took out anger on the children and his mother cared without understanding.

“He made being bookish ok for black kids,” Pinkney said.

In Pinkney’s childhood, many people around him felt liking to read was shameful and even alien. Baldwin seems to have faced that kind of feeling with determination. In “The Devil Find’s Work,” when he read and re-read Charles Dickens and Harriet Beacher Stowe, his mother became so concerned she took the book he was reading and hid it on a high shelf. He scaled the wall to get it back.

He read with an intense need to understand his world or to take himself out of it.

“He has an intimacy with language,” Pinkney said, considering the beauty of Baldwin’s novels. Baldwin became intimate with words, as many and varied as he could find.

“I read everything. I read my way out of the two libraries in Harlem by the time I was thirteen.” … he said in an interview with Jordal Elgrably in the Paris Review in spring of 1984. He learned to write by reading. “I’m still learning how to write. I don’t know what technique is. All I know is that you have to make the reader see it. This I learned from Dostoyevsky, from Balzac.”

In 1948, when he was 24, he left America for Paris with 40 dollars in his pocket and a burning need to get out of New York before grief and anger at his home country made him desperate. His best friend had committed suicide, he told the Paris Review, and he did not want to follow.

France brought him friendship, recognition and hard times. He wrote later about “the days when we walked through Les Halles singing, loving every inch of France and loving each other … the jam sessions in Pigalle … the nights spent smoking hashish in the Arab cafes … the morning which found us telling dirty stories, true stories, sad and earnest stories, in grey workingmen’s cafes.” (This quote of his comes from a May 1961 article in Esquire magazine, “New Lost Generation,” referred to in an article in the New York Times.)

France brought Baldwin heartache too. Entrée to Black Paris, a blog and website of Parisian explorations with a James Baldwin Walking Tour, recalls his deep and understandable anger when a friend loans him clean sheets before Christmas and accidentally gets them both arrested for receiving stolen goods.

In Paris Baldwin published his first novels, “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” about a young black man confronting his strongly religious father, and “Giovanni’s Room,” about a young white American in Paris who falls in love with an Italian bartender.

“‘Giovanni’s Room’ is a very brave book,” Pinkney said.

He remembered reading it at 13, on a family vacation, long before he understood what most of it meant. It moved him then, and it moved him later, rereading it as an adult. Pinckney’s own partner is the British poet and former Oxford professor James Fenton.

Baldwin became widely popular for his novels, especially for “Another Country,” with its riffs on individual and freedom, self-expression, sexual exploration, blues music. And at the end of his life, he became unpopular, Pinkney said, because he would not compromise or tone down his anger or step back from telling the truth about what he saw.

“Well, in retrospect, what it came down to was that I would not allow myself to be defined by other people, white or black,” Baldwin told the Paris Review. “It was beneath me to blame anybody for what happened to me. What happened to me was my responsibility. … I was very wounded and I was very dangerous because you become what you hate. It’s what happened to my father, and I didn’t want it to happen to me.”

He left his country for a time and found a new footing. And then he faced his country, he returned to it, and he marched in the Civil Rights movement and asked his country to face him squarely.

‘… if the word ‘integration’ means anything, this is what it means, that we with love shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are.’ — James Baldwin

Movements like Black Lives Matter are still asking, more than 60 years later. Bolick, reading “If Beale Street Could Talk” and watching the debates about violence by and against the police, said Baldwin’s writing feels more than timely today — it felt necessary.

His clear-headed strength led the Progressive to reprint his 1962 Letter to My Nephew in 2014 because it, too, felt timely and necessary to them — to hear him insist on his right to belong in the country where he was born and to talk about all of the people living there with him: “But these men are your brothers, your lost younger brothers, and if the word ‘integration’ means anything, this is what it means, that we with love shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are.”

That same clear belonging makes “Nobody Knows My Name” a stark analysis in the 2016 and 2020 elections — “I have the right and the duty, for example, in my country to vote,” he wrote; “but it is my country’s responsibility to protect my right to vote.”

How long can someone remain loyal to a country that shows no loyalty to him? I am trying to understand, to imagine, the integrity and the frustration of the young man Baldwin quotes here, like a faithful man finally walking away from a partner who keeps playing him false: “I might … consider being integrated into something else, an American Society more real and more honest — but this? No thank you, man, who needs it?”

In this partnership of man and nation, Baldwin comes out stronger.

He told the Paris Review that he still loved his native country, acknowledging the pain of it: “I think that it is a spiritual disaster to pretend that one doesn’t love one’s country. You may disapprove of it, you may be forced to leave it, you may live your whole life as a battle, yet I don’t think you can escape it. There isn’t any other place to go — you don’t pull up your roots and put them down someplace else. … If you try to pretend you don’t see the immediate reality that formed you I think you’ll go blind.”

‘I don’t think you can escape it. There isn’t any other place to go — you don’t pull up your roots and put them down someplace else. … If you try to pretend you don’t see the immediate reality that formed you, I think you’ll go blind.’ — James Baldwin

And the pain went deep. Pinckney, editing Baldwin’s last novels, saw him worn down by the hostility he had to face, the pressure of being a public figure and trying to care for his extended family.

“As this optimistic, loving soul, he had no place to go in the end,” Pinkney said.

But I think love lived in him still and kept him writing. Writing helped him to survive pain and anger, insults and fame. But he did not write out of rage or grief alone.

“No one works better out of anguish at all; that’s an incredible literary conceit,” he said to the Paris Review.

Reading “If Beale Street Could Talk,” one of his last novels, I feel the anger and fear and sadness, and it comes because of deep friendship and courage.

Tish, the narrator, is fighting for Fonny, a sculptor falsely arrested because he had “found his center, his own center, inside of him: and it showed … and that’s a crime” in this country, she says. Their staunch love for each other and the strength of Tish’s family grounds the book. This is tough-minded and time-tested love. Their believable tensions vibrate like a chord.

“The love and the laughter come from the same place,” Tish says, “but not many people go there.”

James Baldwin did.