The actor playing Tybalt remembered a playground fight. He remembered the blood and the kids standing around cheering it on. He and Mercutio were sitting with me around a rehearsal for Romeo and Juliet, and in that moment the feuds in the Italian city streets felt as real to him as his own high school.

I remember this conversation at Shakespeare & Company 20 years ago. They were two stage veterans talking with a cub journalist from the local weekly. I’d bet they walked in expecting to rehash the press release.

And then we got talking. Actors talk for a living, and they can keep a conversation going endlessly. But we kept talking … and they got off script. They let the conversation move between us, into their own lives.

We kept talking … and they got off script. They let the conversation move between us, into their own lives.

They were there in the room, feeling the tension in the play that ratchets into violence. In the scene they were going to play together, a meaningless confrontation leaves a young man bleeding in the street. They were thinking of the cost and the pain. We could be having that conversation today, and it would feel painfully timely.

(I’m imagining Romeo as a hipster-professional, texting his friends while he waits for his dinner reservation alert, and Juliet rocking short spiky hair and vivid ink, dancing to Nicki and Beyoncé …)

Even then I knew how it can feel when a conversation goes right. You’re holding a space together where the two of you can talk honestly. You’re opening a door so they can tell you what matters to them, what moves them, sometimes what they love or what they fear. You’re building trust. You’re making connections, and ideas flash back and forth between you until you lose track of time.

A universe of conversations

Even in a pandemic winter, at the quietest time of year, I get to talk with so many people … I get to spend a rainy Monday with writers in residence at the Mount and a winter evening with the musicians of Sol y Canto and compare vintage sewing machines with the artists at Wallasauce … and more.

A conversation like that can move you into powerful and unexpected places. It can be sad, raw, exhilarated, angry. When it’s hardest, it can also often be most satisfying. Talking with people can be raw and painful and rock-bottom courageous — and it can be a natural high. A good interview can give the kind of rush I find playing live music at a cider festival with friends in the fall, or watching fire spinners on a mountaintop before a hurricane — when someone has been willing to tell me, this is why I’m here.

I think about that this time of year, as I’m starting to reach out to summer interns, especially in this seemingly endless Covid time, when we’re beginning to see each other face to face again. In all these Zoom calls, I’ve become vividly aware how rare and powerful talking with people face to face can be. And my interns teach me, every summer, how few people know it.

Talking with people is a skill. The way parents talk with their children, the way a rabbi leads her congregation, and the way a I once heard a passerby casually ask a guy in Portsmouth about why clapboards in that wall seemed to fit closer and closer, as though the wall were sliding together — they’re all a skill people learn and practice. The guy on a coastal back street in New Hampshire turned out to be a carpenter restoring his own Colonial house, and he started telling the house’s story and his own.

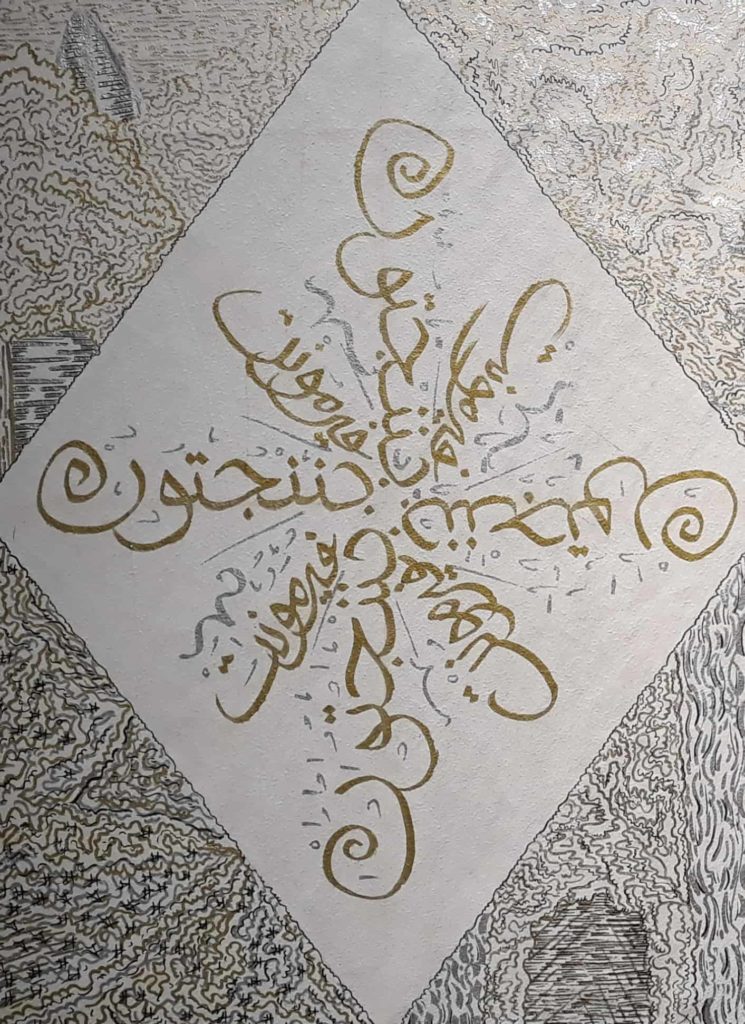

On a winter night at Bennington Museum, artists shared their work in the ‘Transient Beauty’ show, including Ahmad Yassir, who created a calligraphic blend of traditional and new work.

That kind of interaction is a skill, and it’s key to journalism as I know it. The ability to ask the first question and make the connection is a powerful tool. Guiding a conversation is also a skill. Helping the person you’re talking to, moving with them as a question leads to new thoughts — seeing the possible follow-up questions that can lead you both deeper in — feeling your the way along with with who has knowledge you don’t, though he may never have put what he knows into words — that’s a skill.

In the work I do, you need these skills to understand the story. Maybe you start with the practical side. Why do those clapboards look as though they’re compacting into each other? Why are they made of blue spruce?

Then you get from the practical story to the human story. Why are you rebuilding this house? Why are you using the same kinds of wood and the same tools the original builder used? Why are preserving old buildings and learning historic techniques and working at a pace that allows this kind of craftsmanship important to you?

Visitors take in the bright color of Sol Lewitt's murals at Mass MoCA.

And, maybe the hardest kind of question and the most pregnant — you need this skill to get far enough into the conversation to understand the person you’re talking with and hear their experiences. What does it mean that you have the kind of time this work takes? What resources do you need? What history are you preserving, and why do you care so fiercely about making sure it isn’t lost? What role does this work play in your life — is it a comfort, a fascination, a way of building friendship, a solace for loneliness?

And so the skill matters. You need to know what kinds of questions to ask and have a feel for how and when to ask them, when to keep quiet and let someone talk, when to push, how to ease friction, how to stand with someone when they’re feeling their way toward something vital they’re not sure how to say, how to listen for all they’re saying, all they’re implying unspoken, all they’re not saying that matters to them …

Cloteal L Horne will perform in 'Hang,' written by Debbie Tucker Green, at Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, directed by Regge Life. Press image courtesy of Shakespeare & Company

And it’s not a skill many people get to practice. Even people who believe they are interested in journalism may not have had the chance, and they may be intimidated by it. At least three or four times now I’ve had writers, freelancers and interns, get shakingly angry with me because I told them they needed to talk to people. And maybe they were tired, had other concerns, didn’t understand what I was asking — but I think they were afraid.

It is usually easier to read a website than to talk with a PR rep, and easier to talk with a PR rep than a curator, and easier to talk with a curator than an artist. Each step closer toward the creator brings you closer to the real story. And I have to keep calling for the real story, constantly, even with veteran writers — telling them why they need to talk to the creator.

And I do, because I know it’s hard, and I know it’s vital. In another of my first assignments as a fresh-out-of-college cub reporter, a local editor assigned me to write about a woman who had lived through the civil war in El Salvador — and then my editor read the story and told me to write it all over again, because I hadn’t gotten to the heart of it yet. I’ve been thankful for that story and that lesson for 20 years.

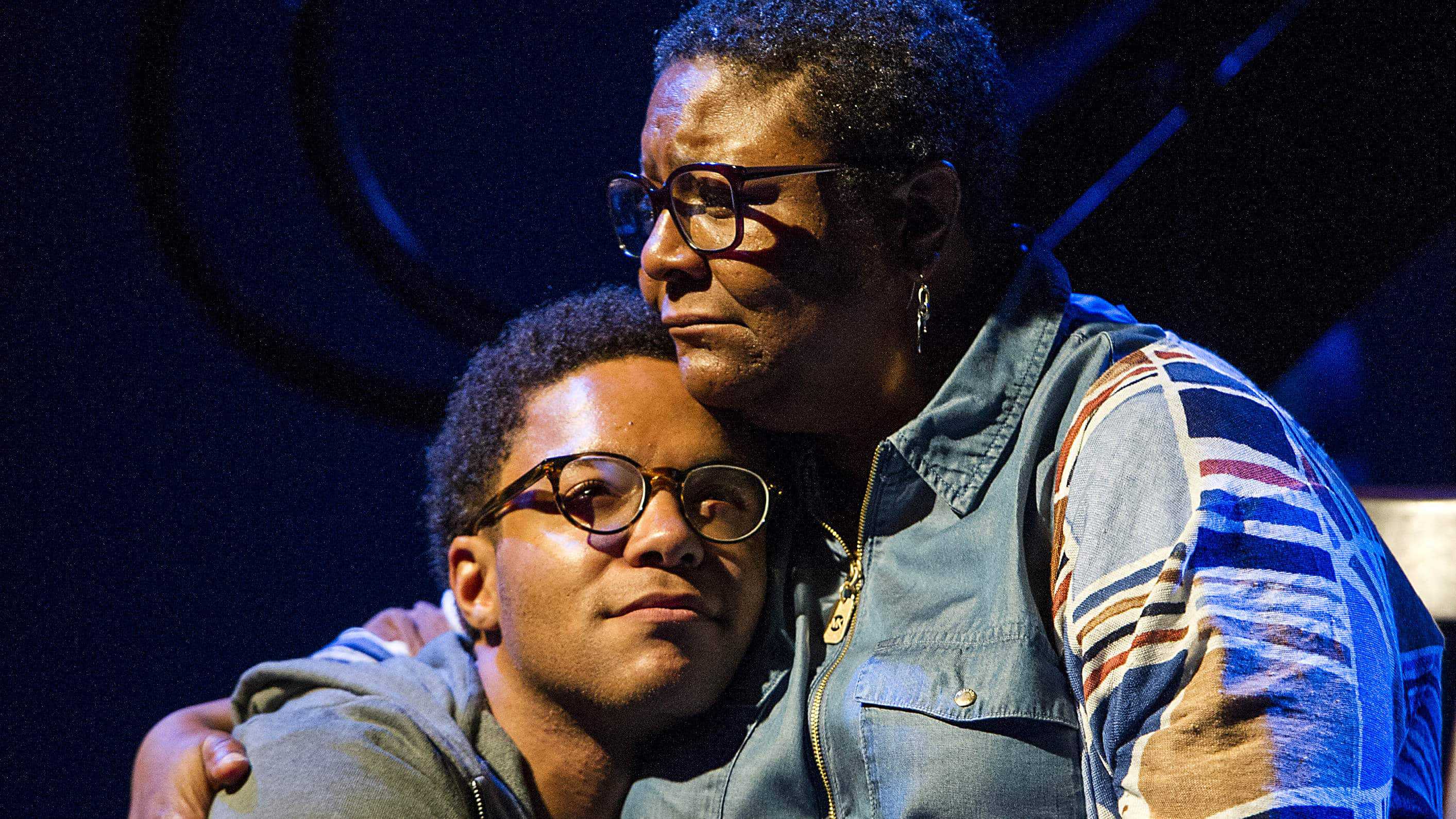

Myra Lucretia Taylor as Bethea and Christopher Livingston appear as Gideon in Harrison David Rivers’ 'Where Storms Are Born' at Williamstown Theatre Festival.

It took a certain amount of stubbornness for me, at 23, to sit on the couch with a woman who still wore the scars of the handcuffs from her political prison, but think how infinitely much more courage it took for her to sit there quietly with me that day. I’m still amazed that she would talk with me. This conversation didn’t take experience on my part. She knew how she wanted to tell the whole story, and she had determined to tell it. All I had to do was to sit with her and listen. And be open.

That’s what I want to teach my interns, if I teach them nothing else. The real point is, the work I do, the storytelling — it’s about people touching people. And that’s important.

Lewis Thomas, doctor, microbiologist and a warmly human writer, has an essay about a pleasure center in the brain that connects to about every other part of the brain — it gets signals from everywhere, and when it’s stimulated, it gives a pleasure stronger than hunger, pain or relief of pain or sensory stimulation. He thinks it’s the feeling, the certainty, of being alive. He calls it the pleasure of children at play and ravens diving into the wind, and of music.

Aimee Doherty and Deaon Griffin-Pressley appear in the comedy As You Like It at Shakespeare & Company in summer 2018.

Darwin, he says, wrote late in his life that he felt overwhelmed with data and could no longer read poetry. And that’s what I’m afraid of. I want my magazine to continue to exist, and journalism to continue to exist, and so I want them to find a way, within the best media we have, to do what they do well.

But apart from the media, when I’m sitting with my feet in the Green River and trying to explain what I want the media to be there for — I think good writing, like music, like painting and poetry, is alive. When you read it, you can feel the writer thinking. In journalism, you can also feel the person the story is about, thinking and feeling.

That kind of writing comes, I think, even in the ordinary town meeting and sewer pipe stories, from a practice of writing and interviewing and research and all. Maybe it all comes down to what the features editor told me shortly after I walked into the Eagle to run their Berkshires Week magazine awhile ago. He said, “talking to people is the fun part.”

How do I explain that to someone who hasn’t felt it?