In Veracruz, on the coast of Mexico, a singer on a warm night is playing a rasguedo, a flamenco strum, the fingers of his right hand flicking down in a rapid fan. In Seville a composer turns from church music to write a secular song on a flat-backed lute with doubled strings.

Across an ocean they influenced each other, and the living pulse of their exchange beats today in their music. Jordi Savall, Catalan composer, performer on viol da gamba and director of the early music ensemble Hespèrion XXI, will explore that mix of traditions in concert with the Mexican musicians of Tembembe Ensamble Continuo at Tanglewood in Lenox tonight (July 7, 2016).

Together they will perform Spanish songs written in the 1500s and folk music from Cuba, Mexico and South America. And they will look closely at a conflict that he said feels all too familiar today.

They will perform work from Renaissance Spanish and Mexican composers, and they will improvise to structures in Spanish music and folk music in the New World, Savall said by phone as he traveled between performances in Spain. One work was written by a composer for Phillip II when he was the most powerful monarch in Europe, and another swayed dancers in the streets in Cuba.

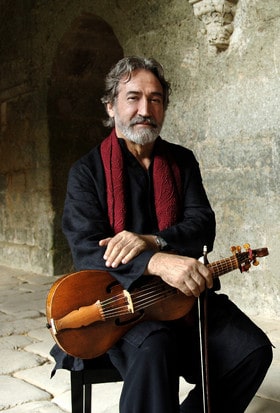

Jordi Savall, director of Hesperion XXI, will perform at Tanglewood. Press photo courtesy of Tanglewood.

What matters is the quality of the music and the interpretation, Savall said. Most of the music connected with oral traditions is music for creating a special atmosphere, a moment of joy. Many times people who have come far from home or people living in fear, in slavery and under force have used music to create their own freedom space. He has recorded Sephardic songs as deep as classical compositions.

“All of these old tunes, Mexican or Celtic or Sephardic, have helped people to survive,” he said. “They have a strong power and spirituality. That is why still, today, after so many years, they touch our sensibility. It is a great moment.”

One world crashed into another when Spanish soldiers came to the Caribbean, Mexico and South America in the 16th century. They came with illness, violence and homesickness. One musical tradition in this performance, Jarabe Loco from the Gulf Coast, has elements of African and Huastecan music from the people who lived here before the Spanish came and the people they brought by force.

Further south, in Lima in 1780, the Bishop recorded what he could of the lives and culture of the people in his city in an illustrated manuscript, the Codex Trujillo del Perú.

“It is a very beautiful collection,” Savall said.

He recorded dances and music, not court entertainments but the music people played among themselves, at home and at festivities.

Savall and the ensembles will improvise their own variations. In Jarabe Loco they always have a new text in relation to the country and to the place, he said, in poetical and rhythmic form. And they will build on the traditional music of the canarios — he sang softly in the rhythm of a 17th-century Spanish dance, patapa-patapa-toure.

Spanish Renaissance music has a strong connection to folk music, he said. Even composers of religious music wrote and collected popular songs for guitar.

“Sometimes music is composed by great composers, and sometimes it is passed down from generation to generation,” he said. “People loved this music and used it to be happy.”

He imagined the musician and composer who recorded some thousand fiddle tunes in Boston, in what is now called the Ryan collection.

“He was far from home,” Savall said, “in Boston, he heard Irish music in a pub, and life was again possible.”

“They were making music together to recover hope. All these people coming from countries devastated by war and poverty, emigrating from one country to another to make life more rich — they used music as a way to remember.”

He includes this music in the concert of the people who came to the Americas from Europe and the struggles they faced, he said, like people forced away from home today, like people in refugee camps, children living in terrible conditions, with no hope and no way to make a better life.

He remembered playing music for children in that chaos and instability.

“They were so happy to listen, to dance, to forget for a moment,” he said.

The memory shook him.

“It is not possible to continue without change,” he said. “There are more than 70 million refugees, and we cannot stop the conflicts. I ask myself how many more people need to die before we stop this.

“We have terror attacks, the resort of too many years without dialog and understanding, reacting with violence to violence. This is no solution.

“We need to resolve problems, taking care for people, giving life dignity and opportunity. People with no possibility of a normal life are ready to commit suicide.”

So he plays this music, to face the past and to recognize pain and beauty and the intricate rhythms of a 12-beat flamenco dance.

“We have to accept what we have done wrong,” he said. “We have music to give people sensibility and empathy. And that is important.”

***

Hespèrion XXI and Tembembe Ensamble Continuo have performed together many times over the years, Jordi Savall said, and Tembembe has recorded on his own record label, Alia Vox.

Savall will perform on an Italian trevle viol (c. 1500) and Pelegrino Zanetti bass viol made in Venice (c. 1553), with lute and percussion from Xavier Díaz-Latorre and David Mayoral of Hespèrion XXI.

And from Tembembe Ensamble Continuo, Ulises Martínez, Enrique Barona and Leopoldo Novoa will perform on some 15 instruments — percussion, maracas and tambourine, violin and harp and many members of the guitar family, from the huapanguera, a large, short-necked bass, to the small, slim jarana jarocha from Veracruz.

This story first ran in the Berkshire Eagle and runs here with their willing permission. My thanks to Features Editor Lindsey Hollenbaugh.