‘The wildness comes from despair?

‘… Sometimes it comes because something has changed inside. A light has gone out … something that makes us feel joy, feel compassion, feel for others.’

A group of friends are keeping a light alive for each other. They are talking in a lighted room on a winter night, like college students in a dorm or actors in a coffee shop.

In The Summer at Gossensass, internationally acclaimed Cuban-American playwright Maria Irene Fornés follows three women fascinated by Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler in the months when the play was first written — as they stand together for the right to create, to define their own experiences and choose their own intimate relationships.

‘I had never read a play that so completely explored my own experience of being a woman in this world’ — MCLA professor Laura Standley on Maria Irene Fornés

Across the 60 years and more of her career, Fornés has had a profound influence on theater in this country and beyond, says Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts associate professor of theater Laura Standley. She considers Fornés one of the most influential playwrights of the last 75 years.

Fornés wrote more than 50 plays in her lifetime, and she won high honors — nine Obie Awards, and her play ‘What of the Night?’ (1990) was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Drama — her plays have been performed around the world, and yet many people in America have never heard her name.

Standley and one of her students, Georgia Dedolph ’24, want to change that, This winter and spring, MCLA has opened a year-long Fornés Festival in celebration of her life and work, they explained in a talk on campus on a sunny afternoon, opening two semesters of programs and events.

The college’s MOSAIC (visual arts), Fine and Performing Arts Department and Theatre Program are joining in a national initiative with the Fornés Institute, an organization dedicated to preserving her legacy.

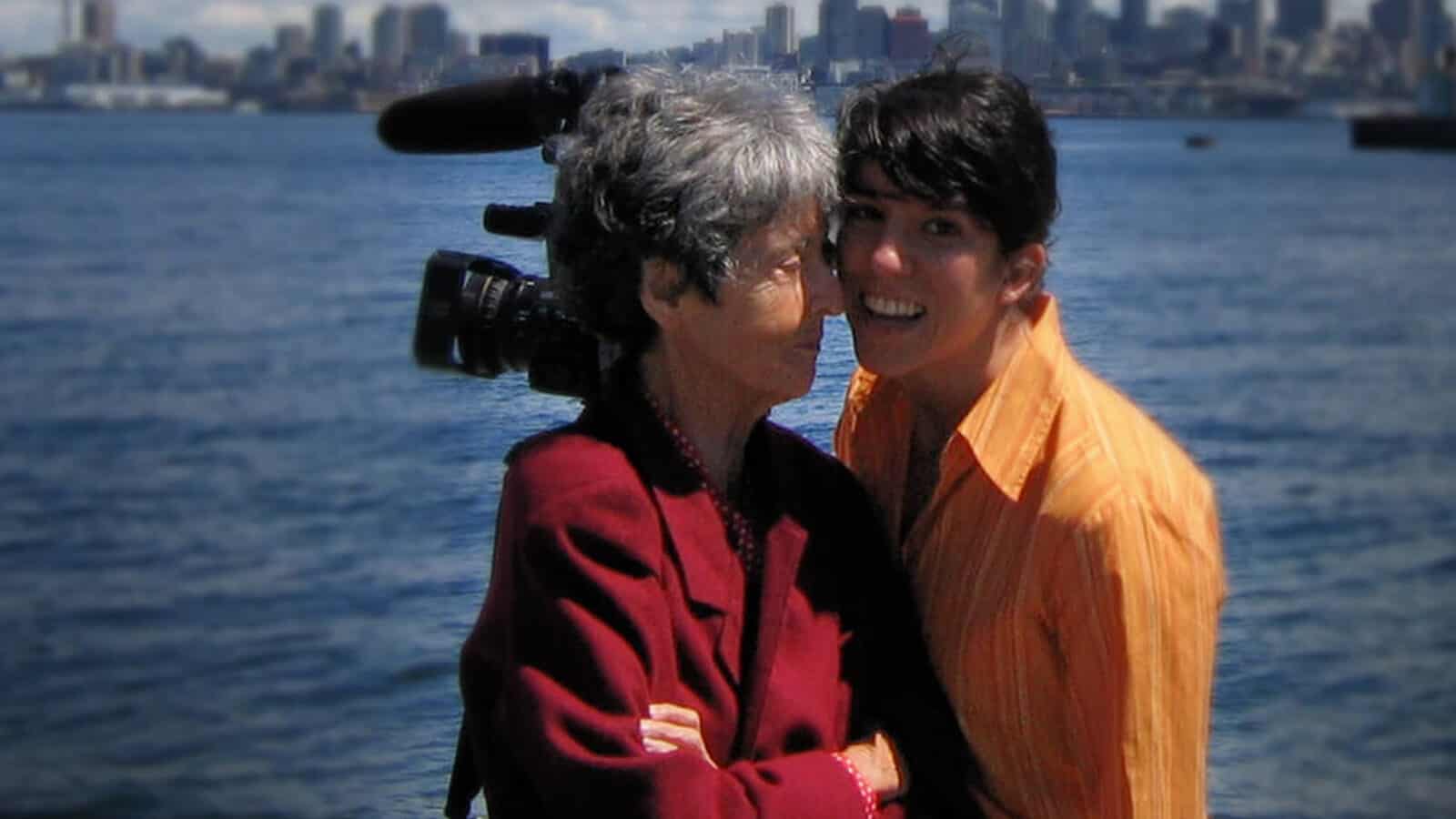

Maria Irene Fornés and filmmaker Michelle Memran grin broadly on a windblown street on the Malecon in Cuba in 2004. Photo courtesy of Michelle Memran and The Rest I Make Up

Standley recalled vividly her first encounter with Fornés’ storytelling. She had the chance to perform in Fornés’ Fefu and Her Friends and found herself immersed in a fascinating and powerful exploration of curiosity and friendship, unlike any play she had ever encountered.

“I had never read a play that so completely explored my own experience of being a woman in this world,” she said.

Though she was studying theater in graduate school then, she had never heard of Fornés and her work — never read or heard about her her plays, had them assigned in class or had a chance to see them performed.

“They are diverse, experimental, complex,” she said, “and they center women … and they have been life-changing for many people, including me.”

‘(Her plays) are diverse, experimental, complex,and they center women … and they have been life-changing for many people, including me.’ — Professor Laura Standley

Fornés has influenced generations of awardwinning playwrights, she said, including trailblazing Latina writer Cherríe Moraga and Pulitzer Prize-winning writers Tony Kushner, Paula Vogel, Lanford Wilson, Sam Shepard and Edward Albee. She has taught and inspired generations of Latinx playwrights. She is often known now as the mother of contemporary Latinx theatre, a leading LGBTQIA+ forerunner and a genius.

Fornés stories continue to feel contemporary and deeply relevant today, Dedolph agreed, as she first made contact wtih Fornés’ work as a student in Standley’s classroom.

“I’ve never read a play I’ve related to more,” she said. “I read all of her published plays, and when (Professor Standley and I) were talking about a directing project for this fall, we had to do this. It’s necessary.”

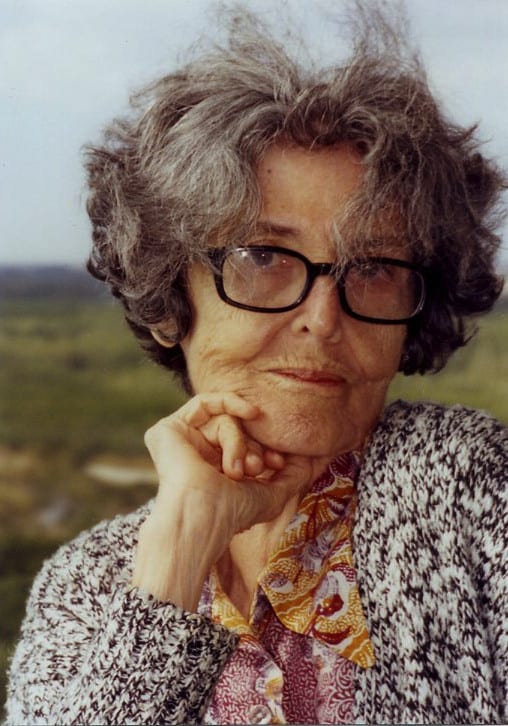

Maria Irene Fornés looks squarely and humorously into the camera in Miami in 2004. Photo courtesy of Michelle Memran and The Rest I Make Up

A festival of plays

December 1 to 3 — Maria Irene Fornés’s early short plays — “Tango Palace” (1963) and “Dr. Kheal” (1968) — directed by Georgia Dedolph 24

February 9 — The Rest I Make Up — screening of the film by Michelle Memran

March 29 to April 7 — The Summer in Gossensass with MCLA Theatre directed by Associate Professor Laura Standley

April 6 — Guest scholar Anne García-Romero, Associate Professor of Theatre at the University of Notre Dame, Fellow of Institute for Latino Studies and Kellogg Institute for International Studies, speaks on Fornés and her work

April 6 — Fornés Legacy Panel Discussion in conversation with Dr. García-Romero, Professor Standley, and the team on The Summer in Gossensass

She will lead the next step in the celebration, December 1 to 3, directing two of Fornés’s early short plays, “Tango Palace” (1963) and “Dr. Kheal” (1968).

She was born in Havanah, Cuba, in 1930, and came to New York with her mother and sister when she was 15. She left school early to work, Dedolph said, and she would always be self-taught and driven, with a deep and unceasing curiosity and humor.

She moved to Greenwich Village, Standley said, and absorbed herself in a world of abstract art, jazz, John Cage, Beat poets reading in the cafés. The Village in the 1950s and 1960s was a center of experiment, and Fornés worked with many innovative minds. She knew the collective of dancers, composers, and visual artists at the Judson Church Theater — Merce Cunningham, Anna Halprin and Simone Forti.

She became a key figure in the off-off-Broadway movement and explored experimental theater with performers like the circle at Café La Mama (founded in 1961 by African-American theatre director, producer, and fashion designer Ellen Stewart).

One of the better known stories about her, Dedolph said, tells the spark of her first play. By 1961, Fornés was Susan Sontag’s partner — they were sitting together in a café, and Sontag was struggling with writer’s block. A friend tried to invite them to a party, and Fornés said we’re going to write and brought Sontag home. Fornés pulled a cookbook off a shelf and pulled sentences that intrigued her and wrote the opening of a dialog.

“Her writing has a magic, gritty and rebellions quality,” Dedolph said.

‘Her writing has a magic, gritty and rebellions quality.’ — Georgia Dedolph MCLA ’24

She often turned to and taught writing in this kind of a collage, she said. Fornés would found the INTAR Hispanic Playwrights-in-Residence Laboratory in New York City from 1981 to 1992, where s taught generations of award-winning and widely produced Latinx playwrights.

She encouraged her students to find ideas anywhere, in photographs, newspapers, artifacts, overheard conversations — she once found a set of records for learning Hungarian. She encouraged writers to interview people and let those conversations offer starting points

Fornés wrote the conversations she wanted to write, Standley said. She took on pressures to conform (and uncountable harsh reactions from critics) and forged on with the courage to speak with passion and honesty.

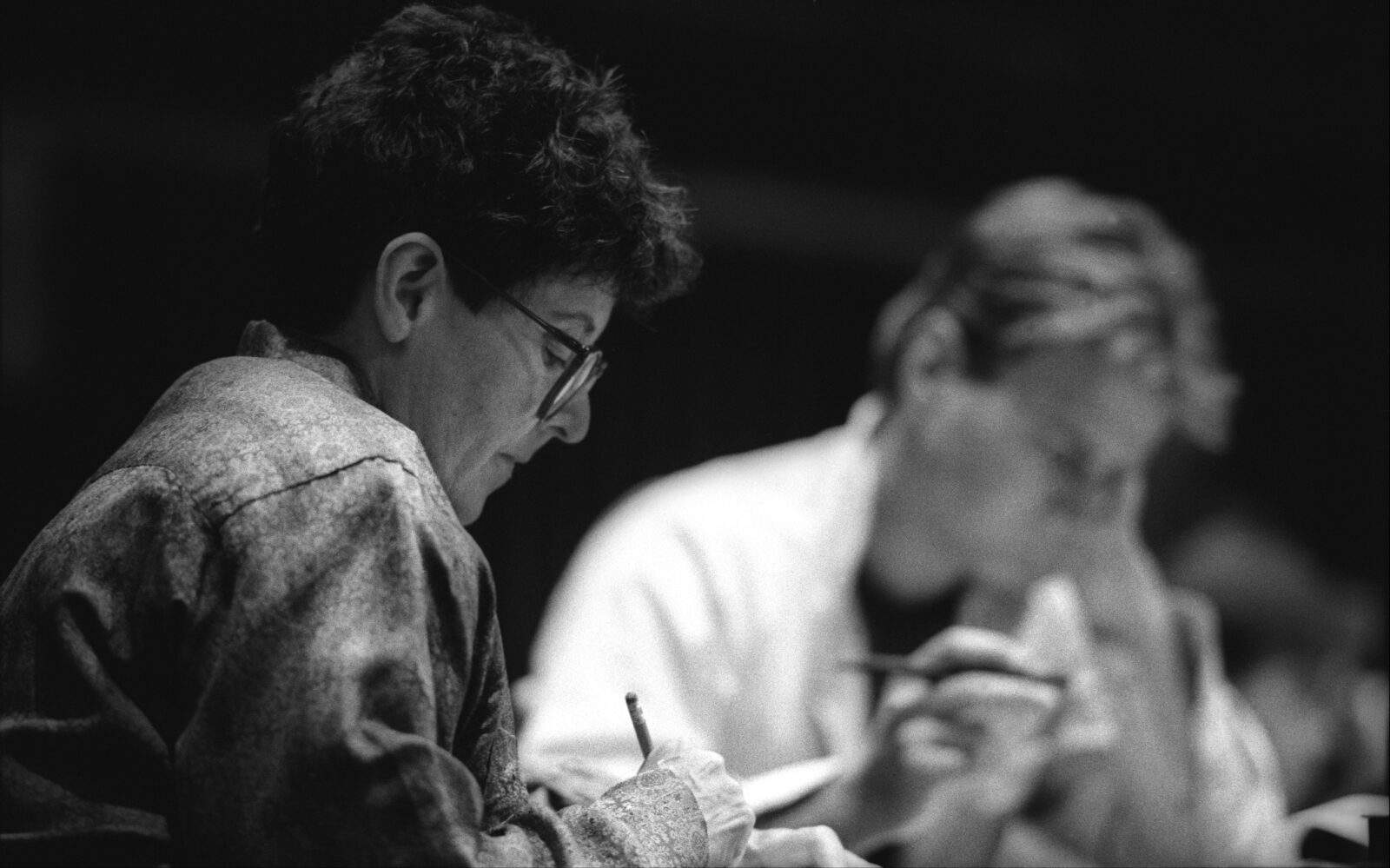

Maria Irene Fornés rests her chin on her hand, smiling with wry mischief in a black and white photo in the 1970s. Photo by and courtesy of Marcella Matarese Scuderi and Michelle Memran and The Rest I Make Up

“She belongs to a group of playwrights disappeared by critics,” Standley said, “because the critics didn’t understand her. Her plays were not published or staged. That’s the argument that has kept her out of the history books.”

Many of Fornés’ characters struggle with confinement and an intense drive to change their lives. They fight for a need to express their curiosity about the world, Standley said, even when their attempts to learn and explore are thwarted. They are finding life and beauty even when they are stuck in desperate and terrible circumstances, and they are afraid their desires will never be fulfilled.

In her early work, Fornés often turns to satire and parody. In Paris she had the chance to see Waiting for Godot, Standley said — “I didn’t understand a word of it,” she wrote, “but I understood the world where it had taken place.”

‘(She confronts) education, right and wrong, balance and truth — how beauty and love are the point of our being here.’ — Georgia Dedolph

She drew influences from absurdists like Ionesco and from abstract art. playing with space, composition and texture, puppets and masks. She creates characters with intensity, Standley said, and plays that create parallel worlds. Theater makers have compared her compared writing to the deep color in Frida Kahlo’s paintings, Vermeer, Zúbaran.

In Tango Palace, Dedolph said, a vicious clown is living in a room filled with objects that represent ‘the acme of artistic expression,’ trying to force their worldview onto an earnest young artist, and the artist struggles with pressure to compromise his passion and integrity, fighting for the strength to break free.

“(She confronts) education,” she said, “right and wrong, balance and truth, how beauty and love are the point of our being here.”

Maria Irene Fornés teaching one of her legendary workshops, in the 1980s - Photo courtesy of Chris Bennion and The Rest I Make Up

In the 1960s and 1970s, Fornés began directing her own plays, because she felt other directors were diluting and denying their energy.

“She became dissatisfied with the comedies she had been writing,” Standley said — “she felt they were inadequate says of confronting the world.”

She began to feel that she was hiding behind comedy. because showing her feelings and ideas more clearly left her feeling exposed. And so her plays begin to shift toward a kind of intense reality. In the spring, Standley will direct one of her later and longer works, The Summer at Gossensass.

Fornés became fascinated with three women who are excited by a new play — Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler. The play is set in the 1890s, as the first whispers reach London about the play opening in Munich. She grew intrigued by the experiences of three real people, Standley said, women who heard about the play as a revolutionary exploration of the lives of women and want to perform it in their own city, in their own language.

Acclaimed playwright Maria Irene Fornés and writer Susan Sontag sit together in New York City in a black and white photograph from the 1960s. Photo courtesy of Robert Steed and The Rest I Make Up

They are plotting together, deeply excited — Elizabeth Robbins, an actor, playwright and essayist, novelist and suffragist, Marion Lea, an actor, and Lady Florence Bell, a journalist, essayist and lover of arts. They pore through newspapers by kerosene lamplight as keenly as contemporary as friends scrolling on their phones.

They were central players in the theater scene in their lifetime, Standley said — friends and colleagues with internationally famous actors and playwrights, Edwin Booth, Oscar Wilde, Henry James, James O’Neill (father of Eugene O’Neill).

And they were taking on no small an adventure. Impossible enough that women in the 1890s want to produce, direct and perform a play at all — these three were already having to hide their writing and creative work, even to the extent of burning their own notes. And to perform a play about women who are strong, outspoken, complex would expose them to outrage.

‘A play needs a listener, a respondent, a witness, an advocate — (We need to) find a way to let art be generous and kind.’ Laura Standley, echoing Maria Irene Fornés

But when only a dozen copies exist, all in Norwegian, the stakes grow quickly higher. The woman who has the British rights to perform Hedda was the mistress of the prince of Wales. The rights to English translations went to a man who knew no Norwegian, and the early translations left out, blunted, censored and misrepresented the original work.

Elizabeth, Marion and Lady Bell are fighting passionately even to see the script — sneaking backstage for a glimpse of a few pages. They are risking violent backlash and charging into an international battle over censorship. And all to feed and grow their delight in theater, their passionate need to make and understand and be heard, and their fire to illuminate one another’s minds.

“A play needs a listener, a respondent, a witness, an advocate,” Standley said, invoking Fornés’ thoughts. “(We need to) find a way to let art be generous and kind.”

This story first ran in the Hill Country Observer — my thanks to editor Fred Daley.