A young man is singing in a low and carrying voice. He holds long phrases on a breath. He is chanting a Hawaiian oli, and the words are his. Nālamakū Ahsing is a Williams student, class of ’21, and he wrote these verses calling to the people who came before him to speak.

He opens a conversation among a community of voices about his college and his home. They speak overhead in this room at the Williams College Museum of Art — a pastor, a professor, a student, a Hawaiian scholar — not giving their names, but giving their perspectives on the photographs, letters and artifacts below that trace links between Williams College and Hawai’i in the 1800s.

The connections run deeper than many people realize, say Sonnet Kekilia Coggins, WCMA’s interim deputy director, and Kailani Polzak, assistant professor of art, co-curators of The Field is the World: Williams, Hawaiʻi, and Material Histories in the Making.

In 1820, Hawai’i was an independent nation, settled centuries earlier by people from the Pacific islands. Within 100 years, the U.S. would take the country as its 50th state. Much would change and vanish — and Williams College would be at the center of it.

Coggins’ mother’s family is from Hawai’i, and Polzak’s grandmother also, and they have both researched the islands. Working with Ahsing and colleagues on campus and in Hawai’i, they are uncovering stories of Williams’ past there.

From the Atlantic to the Pacific

The stories began here with a wooden box. In 1986 it was found in the basement of a dorm, Coggins said. It held 64 objects that a student group, the lyceum, had gathered in the 1800s from many parts of the world.

The college had no art or science departments then, and students who wanted to learn brought in a collection from museums and missionaries and expeditions.

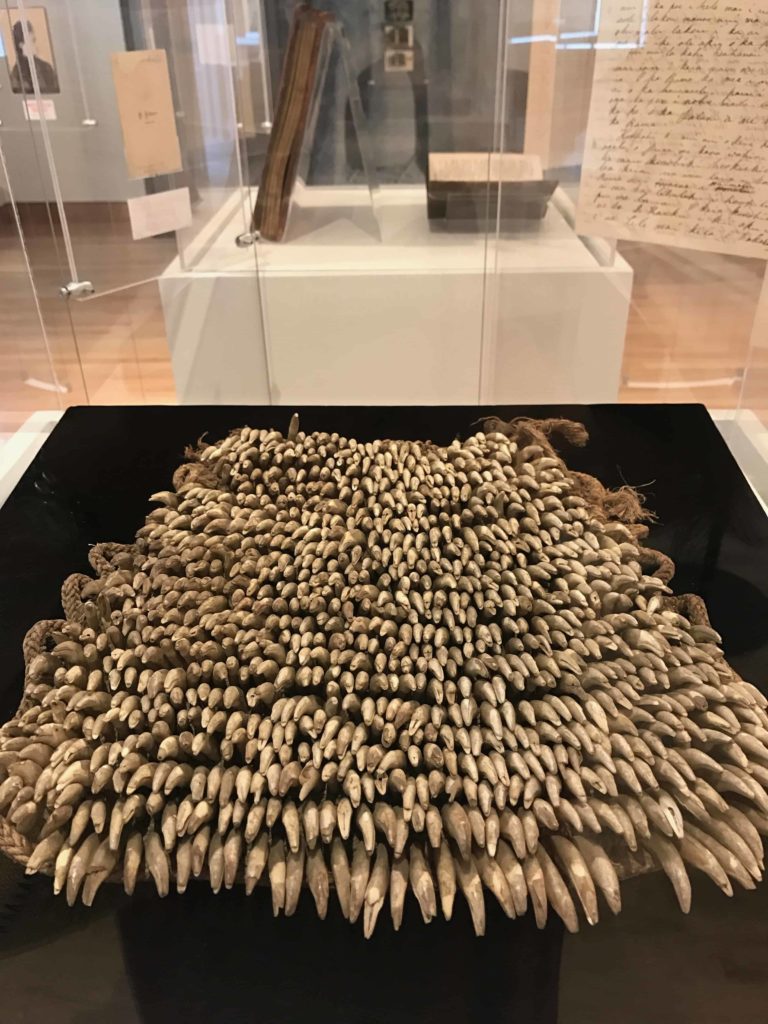

The box held a Hawaiian kupeʻe niho ilio, an ankle ornament made of dog teeth. A man would have worn it to keep a percussive beat as he danced. No one knows how it came here, and Coggins and Polzak are taking it out and holding it up to the light.

In the U.S. now, Coggins said, many people are paying attention to which histories are visible and which are not, and why. These are poignant and powerful questions, and this show asks people to stay with them, and not to walk away from the complexities and the nuances — and the loss — they can carry.

“We are thinking about who gets to tell a story, from what vantage point, who do we listen to?” Polzak said. “Colleges now are taking a look at their own histories. Often these investigations end with a report, polished, this is what we will do; move on. But we need as a community to see these things, to realize they’re here and we are not looking at them … What happens when we look at these things and think about why we haven’t been looking at them?”

When she and Polzak began looking, they found more of the story in plain sight. On campus, a monument remembers the summer day in 1806 when five students lay in a haystack, keeping dry in a thunderstorm. They promised each other that they would dedicate their lives to spreading the Christian gospel, and that pact would sent missionaries around the world.

This moment is important faith heritage for some people, Coggins and Polzak said, and for others a very painful reminder of cultural loss. A minister recalls coming here to kneel on the grass and wrestle with this history. A student walks by the monument and feels it like a slap in the face.

A voice in the recordings shares this pain, looking at a photograph of Hawaiian people at a mission, all wearing white cotton:

My heart is pumping right now. I can feel the tears in my eyes looking at this picture of the First Mission Building in Honolulu, because I grew up listening to this narrative of the treasures and tools that these people from this cold land brought, and … in this moment, seeing this picture, I feel everything that was (and) that is lost through these coercive forms of assimilation.

Missionaries built schools, translated the Bible into Hawaiian and helped to create a written Hawaiian language. But over time their presence would have a profound impact on the islands.

Hawai’i at the center

When Williams graduate William Richards came with a mission in 1823, Hawai’i was an important hub in the Pacific trade between Asia and America. Ships docked from many countries — sandalwood merchants, French Catholics, whalers. Hawai’i was a cosmopolitan center and a meeting point for many cultures in Europe.

Hawaiians were highly literate in their own language, Polzak said, and by the late 1800s many read and spoke English as well.

They were navigating Western and traditional language, faith, values — and the challenges of a small nation that had caught the attention of Asia, Europe and America.

Overhead, a new voice feels this shift in a set of stamps from the last years of the monarchy. Polzak identifies the speaker as Healoha Johnston, Interim Director of Curatorial Affairs, Curator of the Arts of Hawaiʻi, Oceania, Africa, and the Americas at the Honolulu Museum of Art. On each stamp, he says, Queen Lili’uokalani, the last queen of the islands, wears a butterfly pin she had gotten in London, when she came with her mother to take part in Queen Victoria’s Jubilee.

Years later, he says, when her government was overthrown and she was imprisoned in the palace, she made that symbol an assertion of a Hawaiian national consciousness, remembering London, where she and Queen Kapi‘olani were treated as among the highest-ranking monarchs of the world.

Each stamp is overstamped with Provisional Government, showing the change in power in blunt words. Williams alumni played a role here, too, Coggins said. As missionaries influenced culture and politics, their sons formed businesses, including the largest sugar cane cooperative on the islands. Plantation owners would would force through a constitution that stripped power from the monarchy. Three of the men who drafted it were not only alumni — they were in the Lyceum.

Independent island to state — a time of loss

In 1893 the U.S. marines overthrew the Hawaiian government. Coggins followed a timeline in red along the museum wall through generations of Hawaiian kings and queens, to a poignant moment, as it moved from Queen Lili’uokalani to Sanford B. Dole.

Dole led the republic that briefly followed the monarchy, before Hawai’i became a U.S. state. And he too was a Williams alum.

“Something Kailani mentioned this morning,” Coggins said: “Here at Williams the name Sanford B. Dole doesn’t mean anything, but whisper that name in Hawai’i and you get a visceral reaction. That name holds real pain.”

“That was a name I knew, even as a child,” Polzak said.

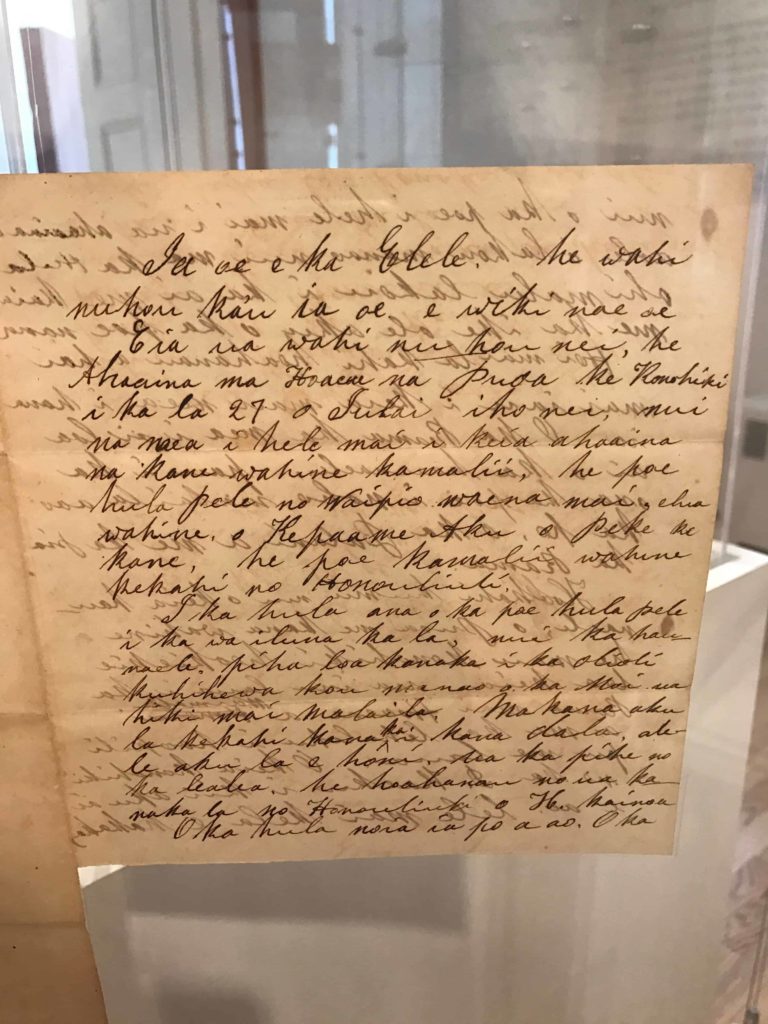

In the college archives, they found new evidence of the loss that came with this change. Ten letters written in Hawaiian preserve mele, stories and chants. They were written to Samuel Chapman Armstrong, the son of missionaries in Maui. He graduated from Williams, and as a young man, as the editor of the newspaper Ka Hae Hawai’i, he put out a call to native Hawaiians: all of you who know the old chants, send them to me so I can record them.

Voices above recall the feeling of reading these letters again.

“We began to read and transcribe. And then there were tears, too. … All three of us were sitting in this room and yet we couldn’t fully comprehend what was being shared with us through time. And that brought a deep sorrow … but also tears of joy when you get small snippets.

“… This is a victory chant for Kamehameha I. And I know that this is a chant for this wa’a, or sailing canoe, from Maui … but what is the chant getting at? I know what it’s about, but I don’t know the poetics. The words themselves have been lost.”

Ahsing helped to transcribe them as he wrote his own.

This story first ran in the Berkshire Eagle. My thanks to A&E editor Jeff Borak and features editor Lindsey Hollenbaugh. The image at the top shows Princess Ka’iulani (1875-1899), heir to the throne of Hawai’i. Photograph in The Field Is the World at the Williams College Museum of Art.