A woman with a thoughtful expression, touched with humor, looks out from a gap in fragments of wood, and above the wreckage around her, the sky overhead is blue.

She may have some reason for laughter. She is the face of Venus in Botticelli’s Venus and Mars, collaged in Joan Hall’s illustration There’s Always Hope.

And in Botticelli’s original, Venus is sitting awake in the grass while Mars sleeps through the teasing of four baby satyrs. One has crawled into his discarded breastplate, two are playing with his lance, and the last is blowing a spiral sea-shell in his ear.

They come in shades of commentary, irony, pleasure and fantasy.

This spring, Mystery and Wonder explores the the Norman Rockwell Museum’s collection of illustrations, taking a broad look at an artform that appears in daily life, said Stephanie Plunkett, deputy director and chief curator at the museum. They come in shades of commentary, irony, pleasure and fantasy.

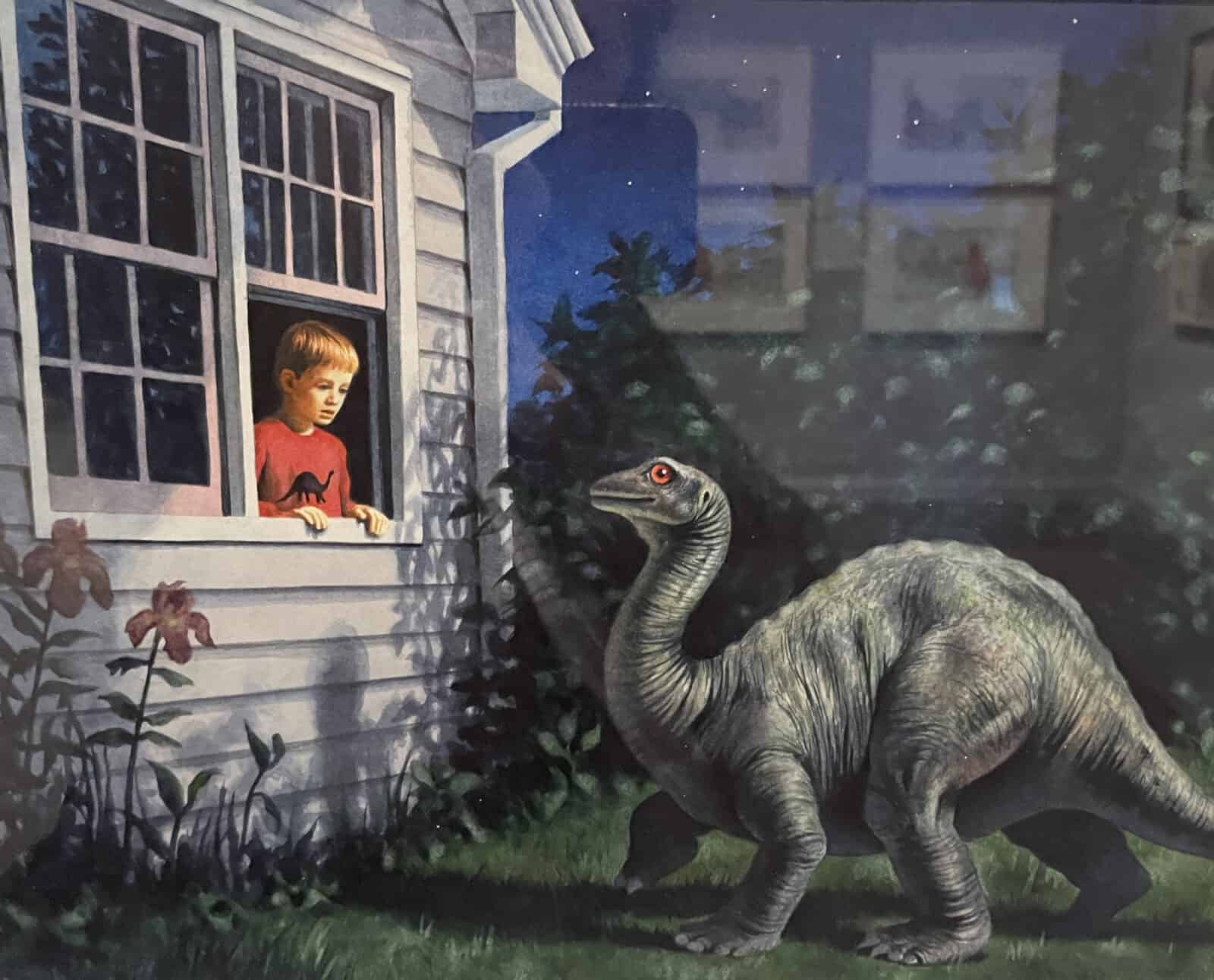

They can take playful and thoughtful tones. Here a boy looks out his window at dusk sees a hatchling apatosaurus on the lawn, in Dennis Nolan’s paintings from Dinosaur Dream. The two of them sit together on a rock ledge, in the sunlight from 140 million years ago.

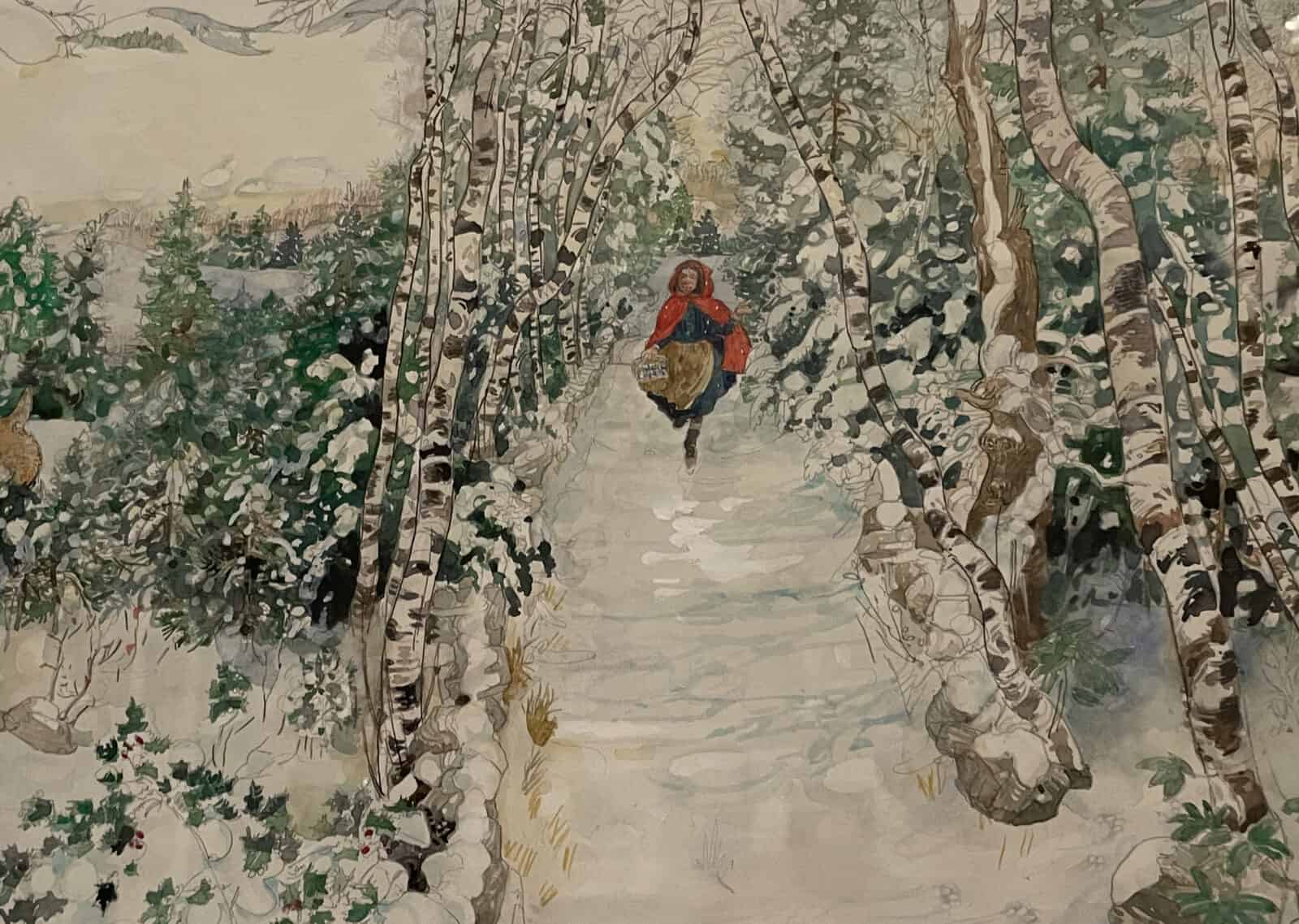

And near them a girl is walking in the snow. Her red cloak stands out vividly against the spruce trees, and a cardinal lights on a branch. Internationally acclaimed, Caldecott Medal-winning artist Jerry Pinkney shows a determined and perceptive young Black woman coming to see her grandmother, in vivid watercolors in his retelling of Little Red Riding Hood.

His family has given them to the museum, Plunkett said, after his passing in 2021. He was working with the museum then on Imprinted, the museum’s 2022 summer show, as guest curator Robyn Phillips-Pendleton gathered contemporary artists in an exhibit that considers representation of people of color in America across more than 400 years.

A boy and a baby apatosaurus sit together on a rock in the sun in Dennis Nolan's Dinosaur Dream. Press image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

Swallows fly in loops in a sunset sky in Thomas Woodruff’s cover image for Anne Tyler’s novel, Breathing Lessons. And Dorothy’s house sails on tornado winds in Thea Kliros’ illustrations for the Wizard of Oz. Press images courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

Pinkney and his family and the museum have worked together over the years. Plunkett recalls the retrospective of his work shown here in 2012 — a sweep of his images over time, in deep, intense color. Sometimes he painted fairy tales like this one, fantasy and fable.

Sometimes he held historical moments up to the light, like photographs no one has preserved — in one painting, Harriet Tubman stood with her father as a girl, looking up at the night sky while he shows her the stars of the big and little dippers.

In another, a gathered firewood in the cold, one of the earliest folk buried in the oldest cemetery in Manhattan. People drew together as they tended a fire or handled a shovel — people who were living enslaved, tending their gardens at Mount Vernon, or working along a river bank in South America.

As the museum has explored a growing breadth of artists in the past 20 years, the museum’s collection has gathered more than 25,000 works, Plunkett said, in many media — oils, watercolors, acrylics, sketches, charcoal.

The Norman Rockwell Museum’s illustration collection has gathered more than 25,000 works.

And still the museum’s illustration collection is relatively new. She traces the beginnings to 1975, and an inflection in 2007 as the museum chose to give more focus and emphasis to expanding. At the time, she said, the museum staff and board were holding a conversation about how much to collect artwork beyond Norman Rockwell’s, and they decided that a broader collection would help them to preserve the artform and create new exhibits.

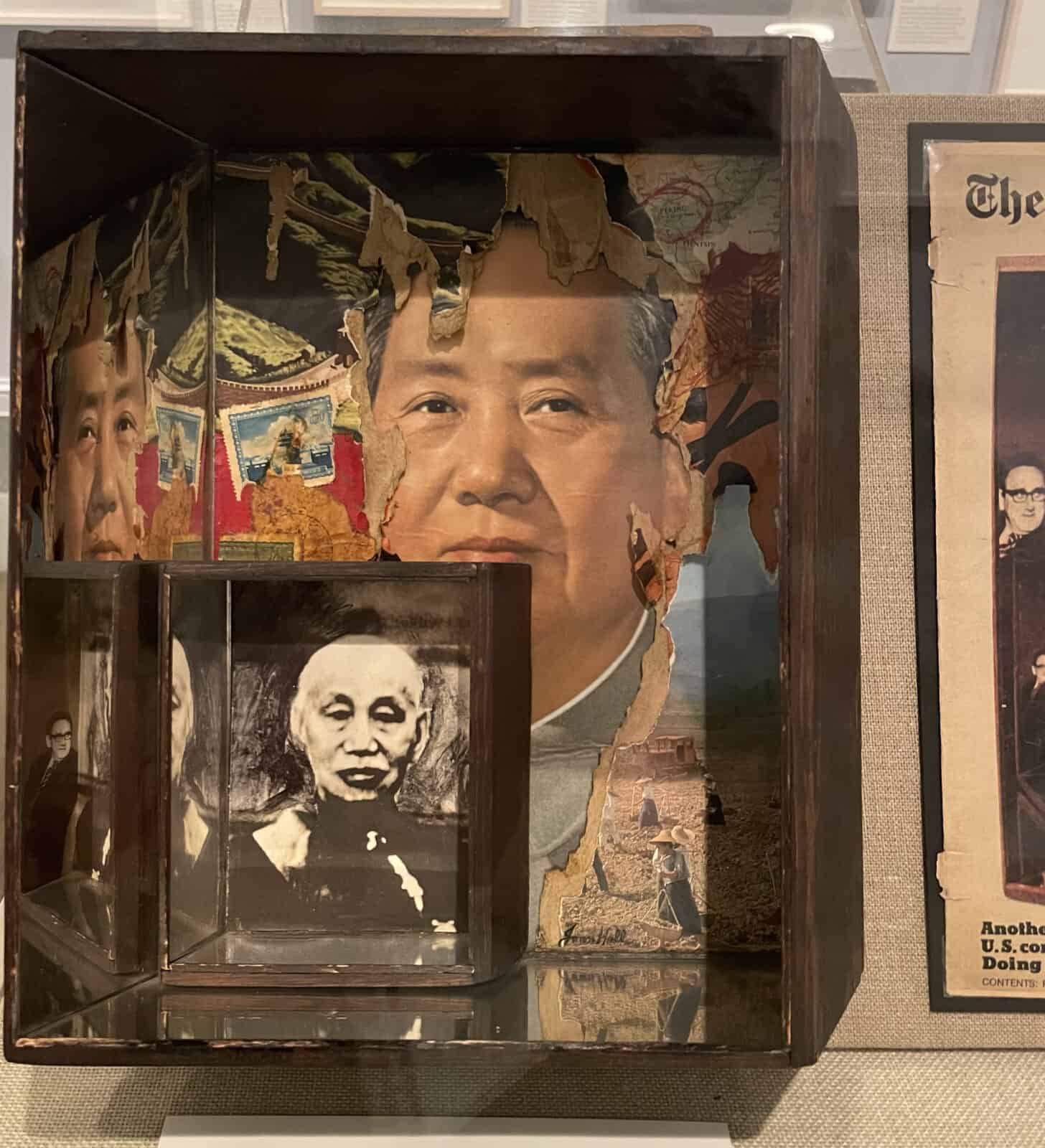

They began with a broad scope, she said, to reflect a wide field — editorial, humor, cartoons, fiction and nonfiction … and even collage. In this show, Hall works in three dimensions as she designs an image reflecting changing leadership in China that appeared on the front page of the New York Times in the late 20th century.

She has created cover art and front-page art for TIME, The New York Times and many more, Plunkett said — as well as collections from the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris to the Museo Rufino Tamayo in Mexico.

Joan Hall's collage artwork, 'Another U.S. Committment: Doing it with mirrors,' explores changing leadership in China, in an image that appeared on the front page of the New York Times in 1975.Press image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

Hall trained with the Martha Graham Dance Studio and the American Mime Theatre, and created sets for performances, before she became known for collage and assemblage.

Here, in a handmade wooden box, a woman is sitting at a table in a wide-brimmed hat and a gown low-cut enough for 18th-century Paris. She has a book, a quill and a cup of tea around her … and a shade made of newsprint with a shade-pull in the shape of the circle symbol for Venus, or for a women.

They all form the cover of a book — Ann Douglas’ study, The Feminization of American Culture — a look at women who tell the kinds of stories that undermine their own strength.

Many of these artists drew for stories, Plunkett said. Along with nonfiction and the daily news, they illustrate fiction, novels and short stories and mysteries. Hall herself has created ink drawings for Dante’s Inferno, Manuel Puig’s Kiss of the Spiderwoman, Don Quixote and Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue.

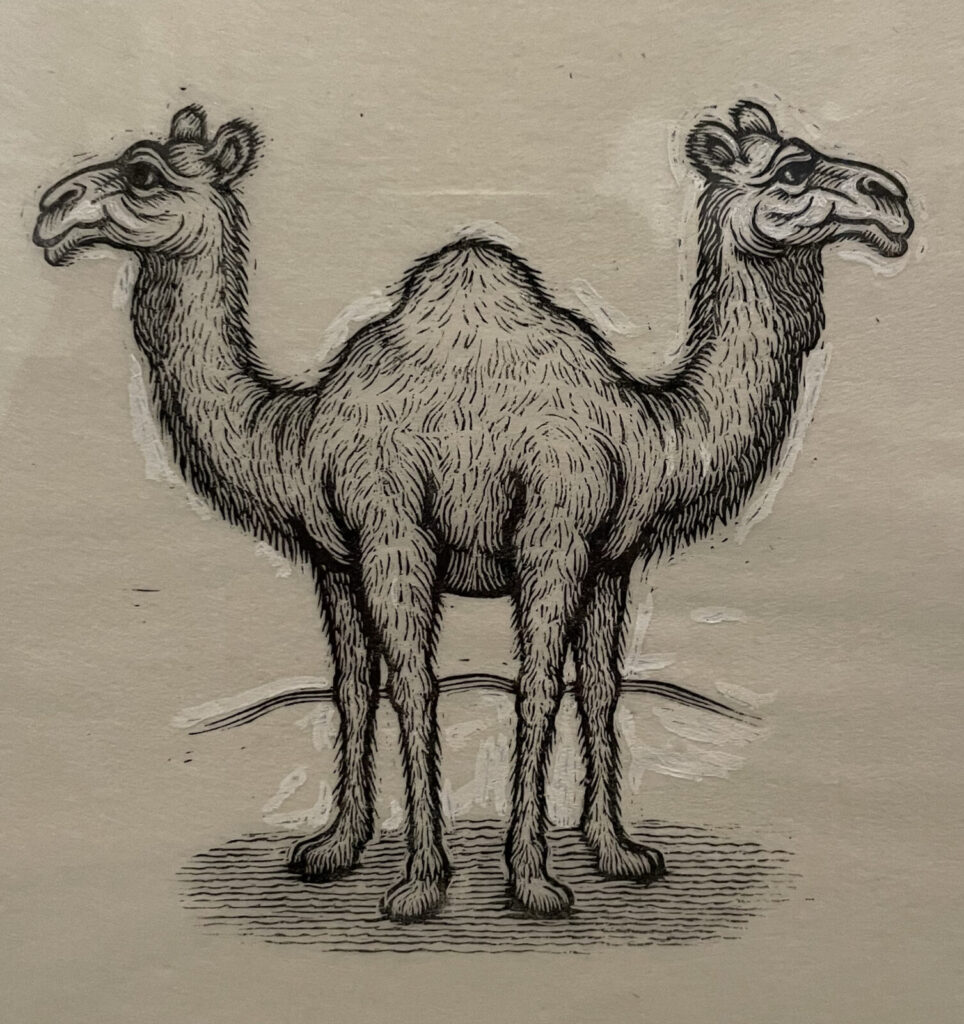

Woodcuts form wordplay in James Grashow’s illustrations for Dubious Doublets — images blending two words that share a root. Some share a sound, a double-headed palindromic dromedary or a a tulip and a turban, from Greek or Persian, a language young enough (relatively speaking) for contemporary speakers to recognize them.

Sometimes they go back to Indo-European sounds. Galaxy and galactic come from galakt, meaning milk. Feather and hippopotamus grow from pet, to fly. And carrots and onions glide on broomsticks, because in Grashow’s hands, weg, strong and lively, traces forward to root vegetables and to witches.

A boy looking out his window sees a baby apatosaurus on the lawn in Dennis Nolan's Dinosaur Dream. Press image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

Nearby, a flock of swallows are wheeling in a sunset sky. They look as synchronized as aeronauts — they form two interlocking rings over an old country road. Thomas Woodruff paints images for the covers of novels by Anne Tyler and Gabriel Garía Márquez.

Living between Germantown N.Y. and New York City, he has taught at Bard College, Plunkett said, and at the the School of Visual Arts for more than 30 years.

For many of them, Julian Allen was teaching nearby at Parson’s School of Design. Here, in a whimsical gathering, he has drawn a group of graceful women in a jury box — all of them mystery writers: Dorothy Sayers in deep green, Agatha Christie, P.D. James.

James Grashow draws a palindromic dromedary, a wordplay in images. With a woman and a web, Joan Hall illustrates Argentinian writer Manuel Puig’s Kiss of the Spiderwoman. Press images courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

Allen began drawing in London in the 1960s, as a freelance illustrator-reporter for The London Sunday Times Magazine and the Observer, and he moved to New York to work with New York magazine. He would create images, Plunkett said, when a photograph did not or could not exist, in some ways like Jerry Pinkney — and like Ned Seidler.

In a painting for National Geographic, he imagines the Moche people in Sipán, on the northern coast of Peru. They lived from 100 to 700 BCE in a thriving civilization along the ocean, and they made beautiful and varied ceramics, and vast temple pyramids.

Seidler imagines the artwork they would have made for a tomb for a leader, Plunkett said, as the weavings and sculpture would have looked when they were newly made — gold and silver, jade and copper, shell and turquoise, vicuña and alpaca wool.

And he imagines the person resting here in honor, as they might have looked 2600 years ago … a they lay on their back in the sun, in wide arm bands and blue sandals, and their tunic open at the neck.

Little Red Riding Hood sets out into the wood in Caldecott medal-winning artist Jerry Pinkney's retelling of the fairy tale. Press image courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum