A girl in a blue dress is riding a see-saw. She is holding on at the apex, and her dark hair falls over her shoulders in summer braids.

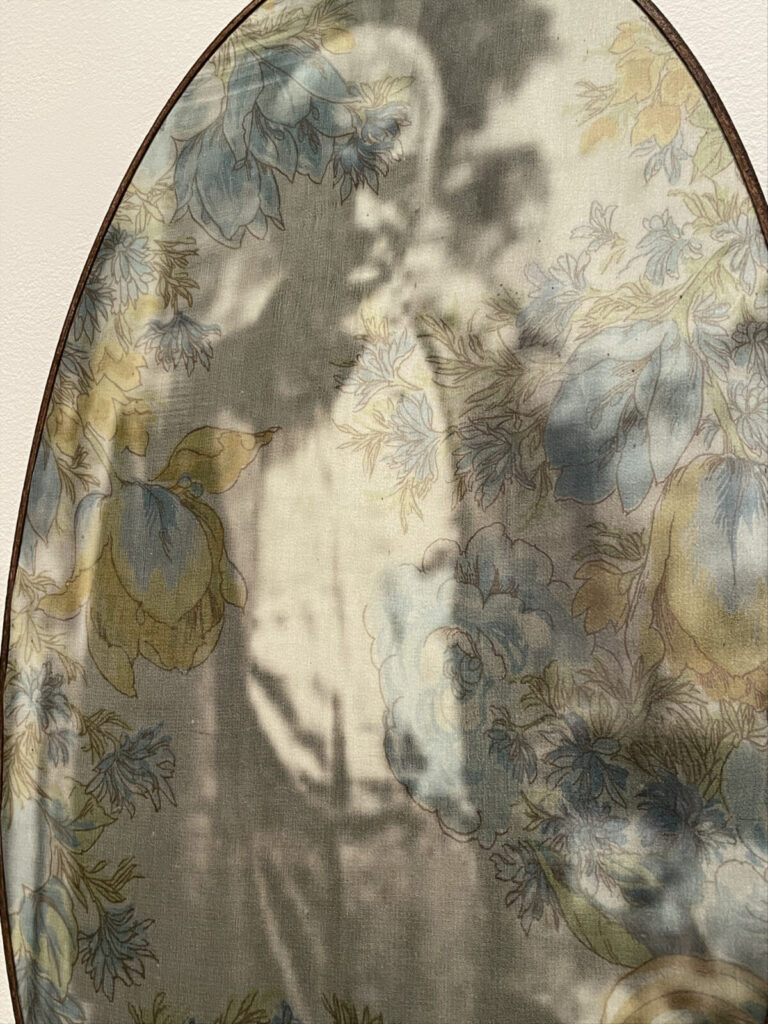

Nationally honored artist and photographer Letitia Huckaby sets her portrait in a hinged oval frame, like a locket to wear at someone’s throat, and in the other half, a set of steps lead up a grass bank to a winter field … where a house used to be.

A body of work called Two Greenwoods brought Huckaby to the center of a community that rose to national prominence a hundred years ago.

W.E.B. DuBois knew Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He walked the busy streets of the thriving Black downtown, and so did Booker T. Washington, founder of Tuskagee University, taking in restaurants, entrepreneurs and music in the city where (according to the Greenwood Cultural Center) Count Basie first discovered big-band jazz.

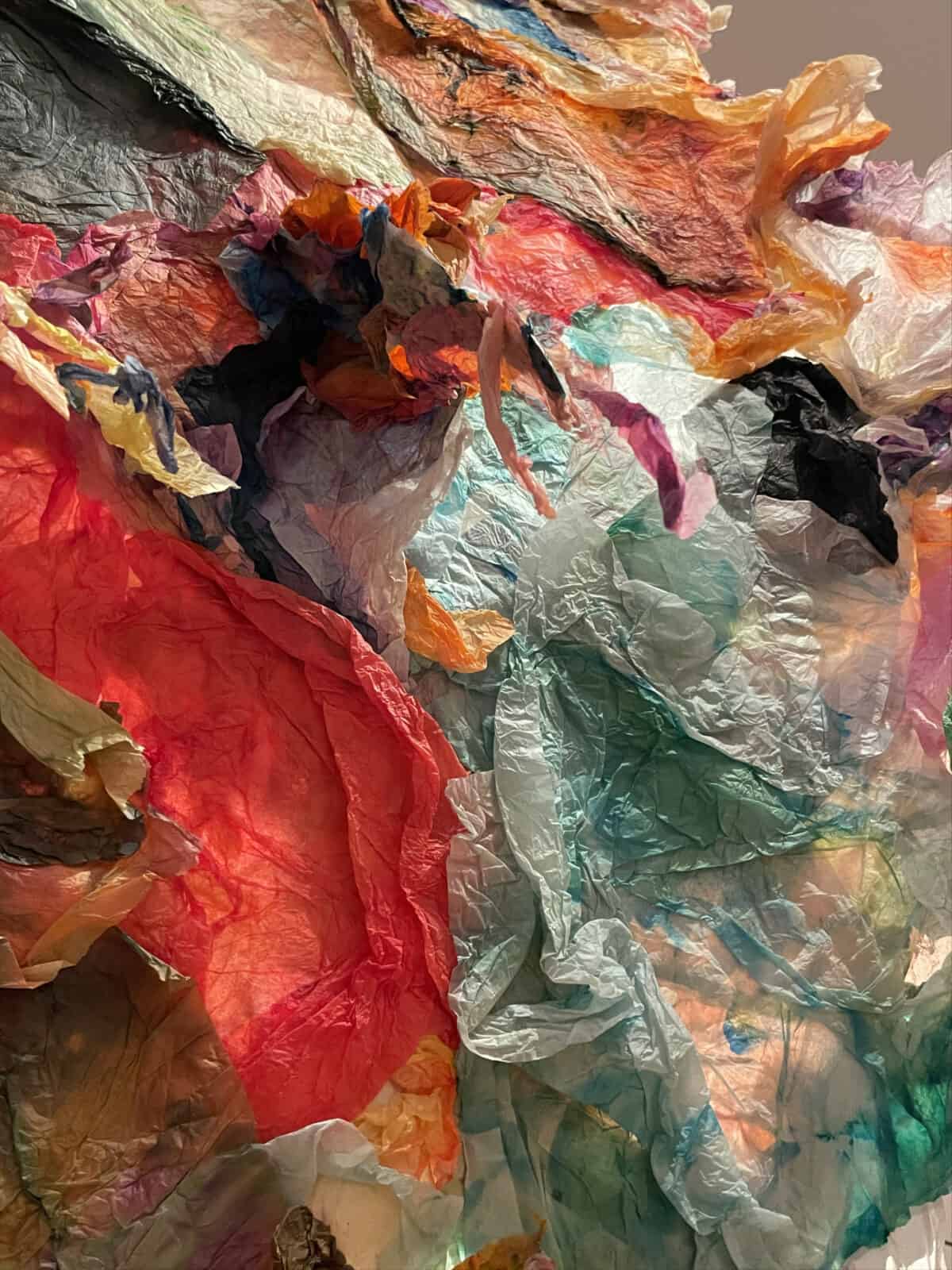

Vivid abstract color spills like butterfly wings in Maya Freelon's tissue ink monoprint, Interjection. Press image courtesy of WCMA and the artist

And then violence struck. In two days, in the spring of 1921, a white mob attacked with guns, bombs and fire, killing and injuring hundreds of Greenwood’s residents and reducing most of its buildings to rubble.

‘Oftentimes when we think of the word emancipation, we use it as a definitive, but it’s not — it’s a process, something ongoing.’ — Letitia Huckaby

“The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre desecrated the Greenwood neighborhood,” Huckaby writes, describing themes in her work — “one of the most prosperous African American communities in the early 20th century.”

In her paired images, she recognizes loss, she said by phone from home in Texas — and she holds in respect all the generations alive today, and the spirit in the community that has grown and persisted in all the years since then.

This winter and spring, she will consider ideas of courage and community, as one of seven internationally acclaimed contemporary artists in Emancipation: The Unfinished Project of Liberation, at the Williams College Museum of Art.

The show, opening around the 160th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, explores ideas of liberation, said guest co-curator Maurita N. Poole, executive director and chief curator at the Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University — the artists are asking what it means to move into the broader society, to be considered a citizen, to have legal rights, and to imagine new futures.

Alfred Conteh’s ‘Float,’ a figure hovering in filaments, appears at WCMA surrounded by Maya Freelon’s vivid color. Sadie Barnette sets a bouquet of red roses on a table surrounded by FBI files she has reclaimed and re-imagined with human feeling. Press images taken by Kate Abbott, courtesy of WCMA and the artists

Vivid abstract color brims in Maya Freelon's tissue ink prints. Press image taken by Kate Abbott, courtesy of WCMA and the artist

From many perspectives, these artists are looking closely at the roots of the nation’s ideas of freedom, and how they play out in the 21st century, she said in a conversation over zoom with co-curator Maggie Adler.

Color cascades like banners in Maya Freelon’s tissue ink monoprints. She calls to beauty, transcendence, ancestry and celebration, she says in the show, with love for her grandmother and for her godmother and namesake, Dr. Maya Angelou.

Alfred Conteh’s celebrated sculpture Float hovers in the air. A figure seems to rise surrounded in helixes, and they are budding like vines — she is scarred and flowering, and she is made from the atomized dust of steel and bronze.

“I hope that people when they see the show,” Poole said, “… they will think about these artists responding to issues that are foundational, and at the core, and they’re fundamental to what it means to be an American.”

‘I hope that people when they see the show … they will think about these artists responding to issues that are foundational, and at the core, and they’re fundamental to what it means to be an American.’ — Co-curator Maurita Poole

The idea sparked in a conversation in 2018, said Adler, the curator of paintings, sculpture and works on paper at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art — and an alumna of the art history graduate program at Williams College.

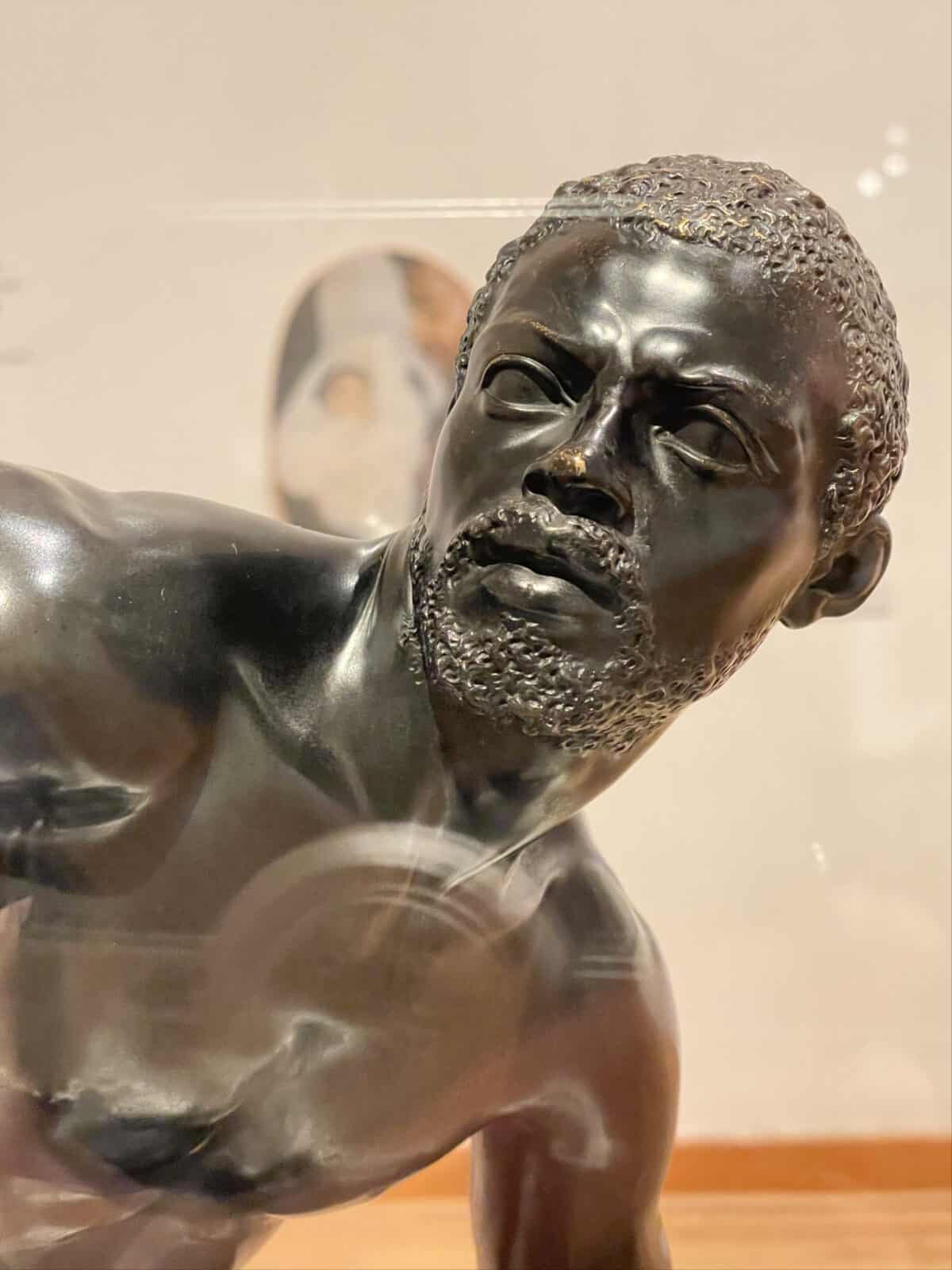

It began for her with a bronze sculpture from the Carter’s collection, “The Freedman,” by abolitionist John Quincy Adams Ward — commemorating President Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation 1863.

Sitting on a tree stump, a man looks toward the horizon. Broad-shouldered and muscular, thoughtful and direct, he holds tension in his body and reflection in expression. He has one hand resting on his thigh and one braced against the log, as though he is half in motion and making decisions.

John Quincy Adams Ward’s bronze sculpture The Freedman (1863) from he Amon Carter Museum appears at WCMA in Emancipation. Press image by Kate Abbott, courtesy of WCMA

He “seems to be grappling with the idea that freedom will demand a new way of being,” Poole writes in the show’s catalog. “This constantly evolving, emergent being requires society to relate to him …” — to relate to him as a man, as a human “constantly evolving, emergent being.”

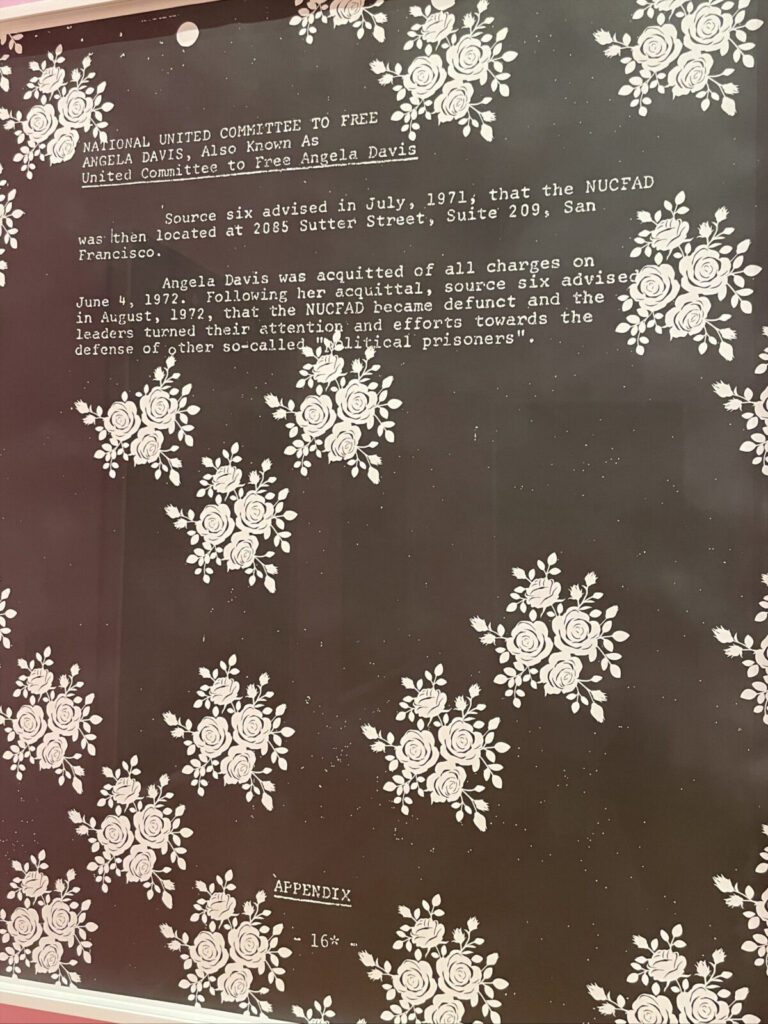

‘When I think about emancipation, I think about abolition. I think about letting go of how we currently organize our societies and planting something new …’ — Sadie Barnette

Adler reached out to Poole, who was then director and curator at Clark Atlanta University Art Museum, at a Historically Black College / University. Poole has also served as a Mellon curatorial fellow for diversity in the arts at Williams College.

Together she and Adler approached Horace D. Ballard, who was then curator of American art at the Williams College Museum of Art, before he moved on to become curator of American art at Harvard Art Museums.

“I was excited about it,” Poole said, “because I thought it would be an opportunity for a new generation to reflect upon those issues, and particularly in the 21st century to figure out how we understand the meaning and implications not only of freedom, but of citizenship.”

Vivid abstract color brims in Maya Freelon’s tissue ink prints. Charlie Lewis appears in pigment on cotton in Letitia Huckaby’s ‘A Tale ofTwo Greenwoods.’ Press images courtesy of WCMA and the artists

She feels students can explore those meanings in greater depth, especially for Black Americans. The artists have opened up these questions here in contemporary sculptural work, she and Adler said.

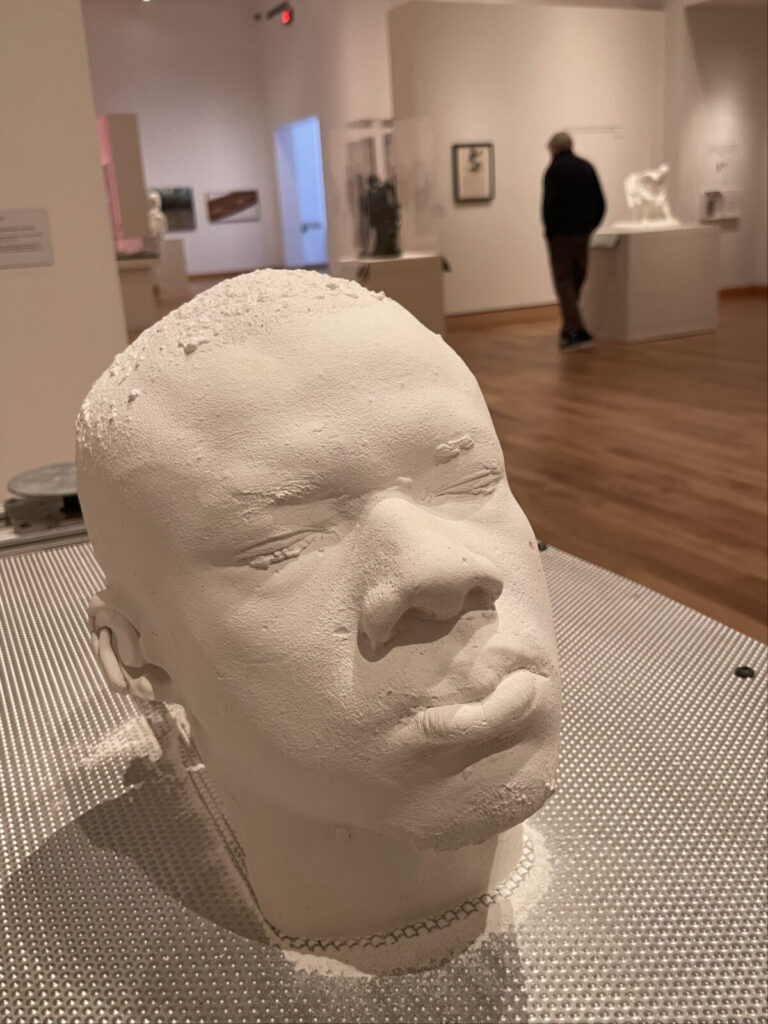

Sadie Barnette explores repression and abolition and resistance in her installations, with fantastical and celebratory elements like glitter. Jeffrey Meris traces challenges in healing and in lived experiences as transient and renewing as snow.

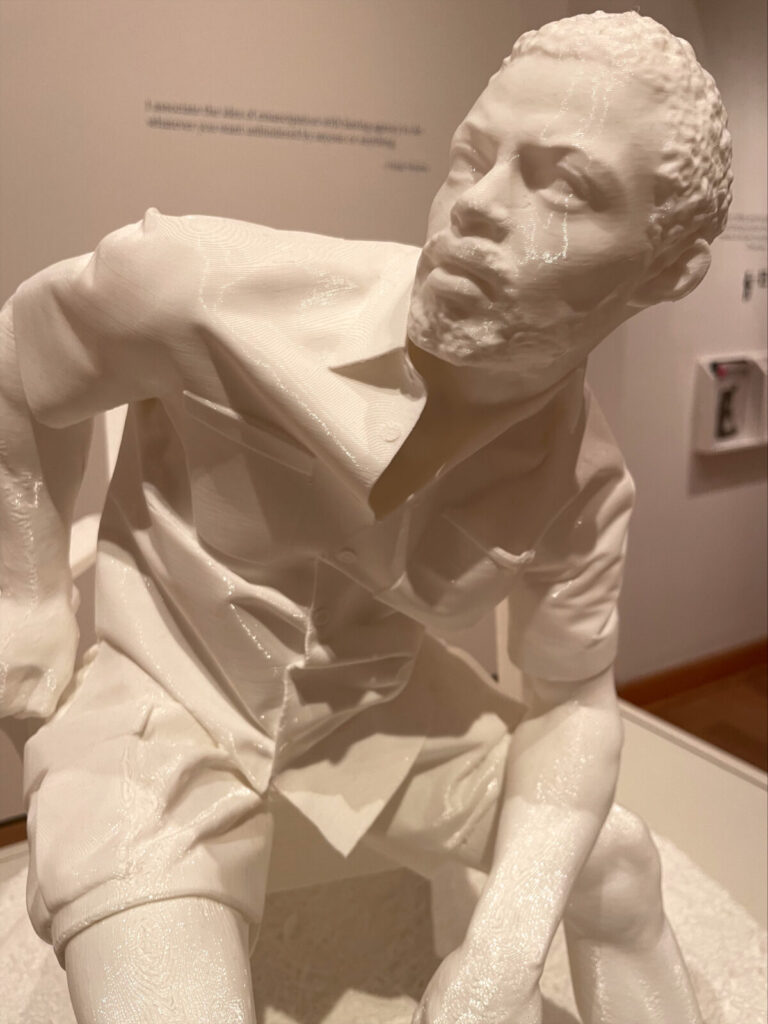

Sable Elyse Smith reveals forms of violence in incarceration. And Hugh Hayden brings the Freedman into the 21st century, a contemporary man echoing his strength and breaking his shackles.

“It was important to all of us that we promote and foster the voices of the next generation of artists,” Poole said.

Sculptor and artist Hugh Hayden sits surrounded by wood, tree limbs, the raw materials of his work. He creates his own contemporary response to John Quincy Adams Ward’s bronze sculpture The Freedman — a 21st-century man in American Dream. Press images courtesy of WCMA and the artist

In her Two Greenwoods project, Huckaby explores two communities related by family and time. Many of the founders of the Greenwood neighborhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, came from Greenwood, Mississippi, she said, where her father was born. He served in the military, and his last duty station was in Oklahoma — so Huckaby has roots in both places.

In the late 1800s, she said, after the Civil War, freedmen’s towns, communities of free Black families, were growing across Oklahoma and Kansas — Oklahoma had so many, they almost became a freedmen’s state.

These newly formed states had land and resources — newly seized from Native nations — and people in the deep South were moving to the plains.

‘The community in Tulsa prospered to the point where they were called the Black Wall Street. They had their own businesses, their own schools, their own hotels, their own theaters, their own … everything.’ — Letitia Huckaby

“The community in Tulsa prospered to the point where they were called the Black Wall Street,” she said. “They had their own businesses, their own schools, their own hotels, their own theaters, their own … you know, everything. And all but one block was completely annihilated in this event.”

The event was a coordinated attack by a substantial number of white residents in the still-segregated city. In two days, May 31 to June 1, 1921, 35 blocks of homes and businesses burned to the ground.

Artist Jeffrey Maris considers pressures on mind and body in ‘A Still Tongue Keeps a Wise Head’ and ‘The Block is Hot: Resurrection’ in Emancipation at WCMA. Press images taken by Kate Abbott, courtesy of WCMA and the artist

Multimedia artists and sculptors — Jeffrey Maris sits under a waterfall of metalwork, and Alfred Conteh raises an eyebrow at the photographer. Press images courtesy of the artists

“More than 300 African-Americans were murdered, more than 10,000 African-Americans left homeless, and more than 2,000 business destroyed,” according to the Greenwood Cultural Center, making it one of the single deadliest and most destructive acts of racial violence in U.S. history — and the effects are still visible, though the community continues to work together for change today.

When Huckaby first came to Tulsa, she said, she talked with descendants of the founders. And she found generational trauma within the community. The centennial brought them into the news, she said, but they felt sensationalized, turned into a spectacle where no one was giving them anything constructive in return. So she explored the past through her own family connections.

“I ended up photographing a city block in Tulsa, near where the Greenwood community was, that had no houses,” she said. “… all that was left was stairs that would have led to porches … and it was a poetic representation of the community that was lost.”

‘I think of emancipation as being collective work not just for the people of the African diaspora but more universal for all humans.’ — Jeffrey Meris

She knows the first Greenwood, in Mississippi, very well, because her grandmother lived there, and Huckaby went back to photograph the block of houses where her father was born and raised. And her mother went with her.

“My father’s deceased,” Huckaby said, “and after he passed away, my mother left Oklahoma and went back to Louisiana, where she was originally from … And so we drove to Greenwood, Mississippi, which is in the Delta.

“… And the drive brought back so many memories to her. That was probably the most precious part about my making that body of work, to listen to her reminisce about driving up to visit him in Greenwood and meet his parents … She’s the one that was able to point out to me exactly where the house was … So I learned a lot about him through her, but I also learned more about her.”

Vivid abstract color brims in Maya Freelon’s tissue ink prints. Press image taken by Kate Abbott, courtesy of WCMA and the artist

Acclaimed artist Maya Freelon sits beside a bright waterfall of her tissue ink prints. Press image courtesy of WCMA and the artist

The role of family, and the role of family history, have become a through-line in the show, Adler said. And so has the role of the body. Artists reckon with violence perpetrated against the body, and they uphold love, held in the moment and passed down through generations.

Freelon also remembers her grandmother in her work, creating vibrant hues and cascading shapes with found objects.

“My grandmother used to tell me we came from a family of sharecroppers that never got their fair share,” she writes in the exhibition catalog. “… She grew up during the Great Depression and knew what it was like to need and not have.”

“… She taught me how to make something out of nothing, how to make a way out of no way, and how to make quilts piece by piece. …

Vivid abstract color brims in Maya Freelon's tissue ink prints. Press image taken by Kate Abbott, courtesy of WCMA and the artist

One day, Freelon writes, looking through her grandmother’s attic, through old Jet and Ebony magazines and books signed by James Baldwin and Alex Haley, she found tissue paper that had soaked up color from the damp.

“This watermark,”she writes, “what many would call an accident from an old leaking pipe, changed the trajectory of my artistic career.”

‘My grandmother … taught me how to make something out of nothing, how to make a way out of no way, and how to make quilts piece by piece.’ — Maya Freelon

Huckaby too invokes her family and her past in the cloth that carries her images.

“I was printing on heirloom fabrics for a while,” she said, “quilt tops that my great-grandmother had sewn. So there was this connection to past generations.

“Sometimes people I hadn’t even met before, they had passed before I was born, but they left these artifacts that I then was able to use in my practice and create a whole conversation with them.”

“… And I’m really attracted to a kind of Southern aesthetic when it comes to color. Especially in Louisiana, there’s a lot of color in the architecture in low-income communities, in the Black community. You see a lot of vibrant color.

“And there’s a richness just to the landscape in the South … it’s kind of like that red clay, and I don’t even know how to explain it, but I feel like that influences my color more than anything else, just the look of the South.”

‘I ended up photographing a city block in Tulsa, near where the Greenwood community was, that had no houses … all that was left was stairs that would have led to porches … and it was a poetic representation of the community that was lost.’ — Letitia Huckaby

Silhouettes form on cotton cloth like people seen through a window. Washes of color touch the walls behind them. In Bitter Water Sweet, a new body of work, Huckaby has talked with the descendants of the founders of Africatown in Mobile, Alabama.

“It’s the only freedmen’s town that I know of that was actually started by Africans,” she said — “They hadn’t been enslaved for along period of time. So their descendants still know who their ancestors were.”

In 1860, 110 people of the Dendi, Fon, Isha, Nupe and Yoruba in West Africa — living in and near Dahomey, now Benin — were kidnapped and enslaved and brought to the U.S. aboard the Clotilda, one of the last known slave ships to arrive in the United States. A white Alabama businessman,Timothy Meaher, smuggled them in illegally even by U.S. laws at the time.

Letitia Huckaby honors the descendants of the founders of Africatown in Emancipation at WCMA. Press image courtesy of WCMA and the artist

And in a rare convergence, their families today know their names. Abile, Gumpa, Jaba, Zazoola, Kêhounco, Kupollee … Some were couples, some families and some children (according to Margaret Brown’s recent documentary film, Descendants). They were forcibly divided and sold in Mobile and Selma and elsewhere, a kind of forced removal that white slaveowers inflicted constantly on enslaved people — one reason the kind of knowledge Africatown has held onto has become so rare.

But emancipation and the Civil War came, and a group of the survivors from the ship formed a community in 1867. They shared relationships, experiences, culture, and passed them down through their families. And their descendants have fought for generations to keep that knowledge.

“They know what areas their ancestors were from in Africa, and customs,” Huckaby said, “something they still hold on to.”

‘They know what areas their ancestors were from in Africa, and customs, something they still hold on to. And in some cases they know what their ancestors looked like … That’s mind-blowing to me.’ — Letitia Huckaby

They built a heritage house, she said, a museum of their own, with photographs over the generations, with writings, with artifacts. They have family stories.

“And in some cases they know what their ancestors looked like,” she said, “because when they came, there was images made of them. That’s mind-blowing to me.”

They even have oral histories. In 1927, Cudjoe (Kazoola) Lewis shared his story with internationally acclaimed folklorist, novelist and playwright Zora Neale Hurston. She wrote a book called “Barracoon” based off of her interviews, Huckaby said. (A barracoon is a jail where enslaved people were held.) Of the group that came over on the ship, Cudjoe was one of the last to pass away.

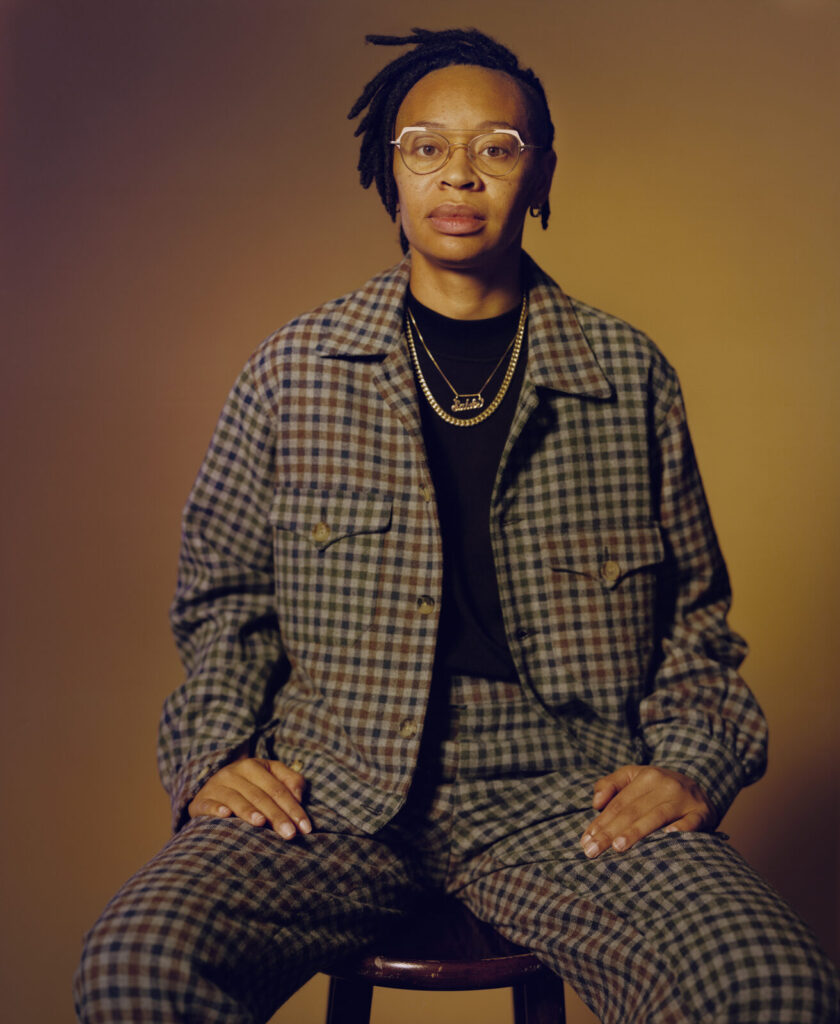

Multimedia artist Sadie Barnette looks clearly into the camera, surrounded by paintings and drawings. In ‘Emancipation’ at WCMA she creates an installation incorporating FBI files she has reclaimed and re-imagined with human feeling. Press images courtesy of WCMA and the artist

“He was a bit of a storyteller,” Huckaby said, “so people would come into Africatown to hear his stories and record their own.”

On her own trip, she photographed descendants of the founders. They have held elements of their community together for more than 150 years, she said, even though for generations they were not allowed to talk openly about their shared past, for fear of retaliation.

“But now they can openly talk about it,” she said, “and they don’t want to stop. They want to just keep telling their story.

“I think that’s the part that they cherish the most, being able to know something about their ancestors, the way they live, the kind of things they said, and have that passed down and be able to continue to pass that down. When you go to community meetings it’s all generations there. It’s grandparents, it’s working adults, it’s teenagers, it’s little kids — they’re all there to of absorb and keep their history alive.”

Sable Elyse Smith interrogates violence and the prison system in her sculpture Trappin I,’ with Jeffrey Maris’ images in the background. Press image courtesy of WCMA and the artist